By Dr. Michael Mandel, Chief Economic Strategist; and Dr. Robert Popovian, Senior Fellow at PPI

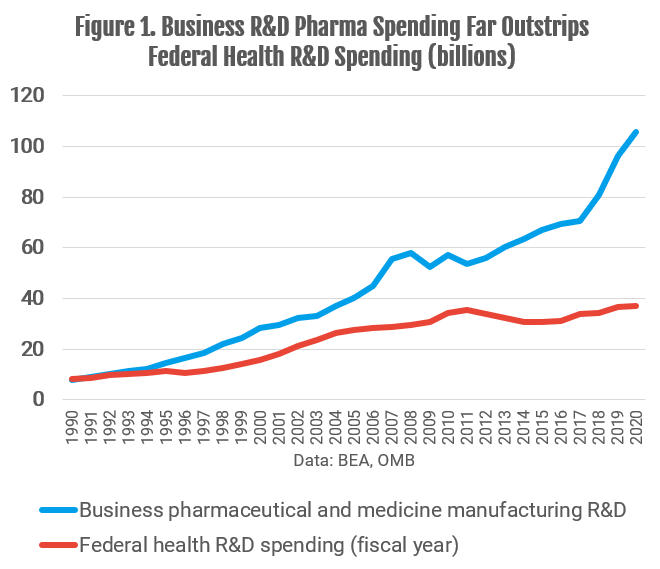

As Congress is considering the shape of the $3.5 trillion reconciliation bill, one of the biggest flash points is drug pricing reform. Drug price reform is very popular, but when you look closely at the data, as we did in our February 2021 report, the evidence for out-of-control drug price increases becomes much less compelling. Spending on drugs, net of rebates and discounts, is basically flat as a share of GDP over the past decade. At the same time, the pharma industry has boosted spending on R&D much faster than the federal government. In 2020, the U.S. pharma industry spent $106 billion on R&D, almost triple the $37 billion in health R&D coming from the federal government (Figure 1).

Equally important, pharma manufacturers’ revenue, net of discounts and rebates, increased by only 11%, or $36 billion, between 2016 and 2020, according to a report from the IQVIA Institute. Taking the industry as a whole, all of that revenue gain went into increased R&D spending.

That’s not to say that some people aren’t hurting. In 2018, only 1 percent of Americans paid more than $2,000 in out-of- pocket drug expenses, not including Part D premiums, according to our analysis. That’s a small percentage, but a significant number of people in the aggregate.

Moreover, data analyzed by PPI and others suggest that the major issue irritating most American families is the insane number of copays that people have to pay as they get older. On average, the typical American between the ages of 50 and 60 fill almost thirty prescriptions per year, while the typical American over 65 and over fill almost 50 prescriptions per year. Most drugs are covered by insurance, but even when each copay is small, these numbers add up quickly and are a growing drag on household budgets. In an October 2019 report, we call this the prescription escalator, since the number of prescriptions — and copays — rises sharply with age.

The problem is that the centerpiece of the drug pricing reform proposal–broad Medicare drug price negotiation–will almost definitely hurt R&D and new drug development without actually addressing most of the co-pays that Americans pay. A recent CBO study estimates that drug price reform (similar to what has been proposed) would lead to 59 fewer new drugs over the next three decades. Moreover, key lines of drug development may never even be funded, leading to missed opportunities for saving lives and reducing medical costs in the future. That’s unfortunate, coming after a year when the industry outperformed the rest of the world by developing “gold standard” vaccines in record time.

Given the current levels of R&D spending, excessively squeezing the revenues received by pharma companies will inevitably translate into fewer new drugs. That implies Democratic Representatives Scott Peters (D-Calif.), Kathleen Rice (D-N.Y.) and Kurt Schrader (D-Ore.), who voted against the drug pricing proposal in the House Energy and Commerce Committee markup process, have solid grounds for worrying that such legislation will undercut investment in innovative drugs.

The drug pricing proposal being considered does contain some good features, including reforming Medicare Part D to cap catastrophic spending. But from a political perspective, it should also deal with the prescription escalator problem that is a key driver of the negative feelings towards drug prices. That means capping out-of-pocket drug expenses, not just for Medicare Part D but for all medical insurance. We examined this in our February 2021 report, “Memo to President Biden: A Reality-Based Approach to Drug Pricing.” In that paper, we support a cap on out-of-pocket costs for drugs, including copays, similar to legislation proposed in 2018. We also support a shift to point-of sales rebates, which should benefit consumers and align their incentives with actual net prices. Getting more transparency into the system is essential.

Finally, we need a better payment scheme for new drugs, especially potential cures for major diseases that are socially beneficial and cost-saving over the long run, but expensive to develop. The most straightforward solution is a shift to outcome-based pricing, which will get new drugs to market faster while having the pharma companies absorb more of the risk.