Source: Teresa Jordan. https://gdr.openei.org/files/899/GPFA-AB_Final_Report_with_Supporting_Documents.pdf.

Next-generation geothermal technology shows promise as a clean and potentially abundant baseload power source with relatively limited environmental tradeoffs. One method, Enhanced Geothermal Systems (EGS), uses drilling technology developed for hydraulic fracturing to access ubiquitous heat sources deep below the surface. EGS has yet to become a major component of the U.S. grid and few plants have been built east of the Mississippi despite indications of feasibility. To solve two of the largest hurdles inhibiting the adoption of EGS (underinvestment and public skepticism toward renewables), the Progressive Policy Institute (PPI) urges the U.S. Department of Energy to provide funding for three EGS pilot plants in Pennsylvania and West Virginia, energy-exporting states that produce large quantities of fossil fuels and show high geothermal potential. This will demonstrate EGS’ widespread viability, bolster public and political support for the technology, and garner increased investment for accelerated rollout.

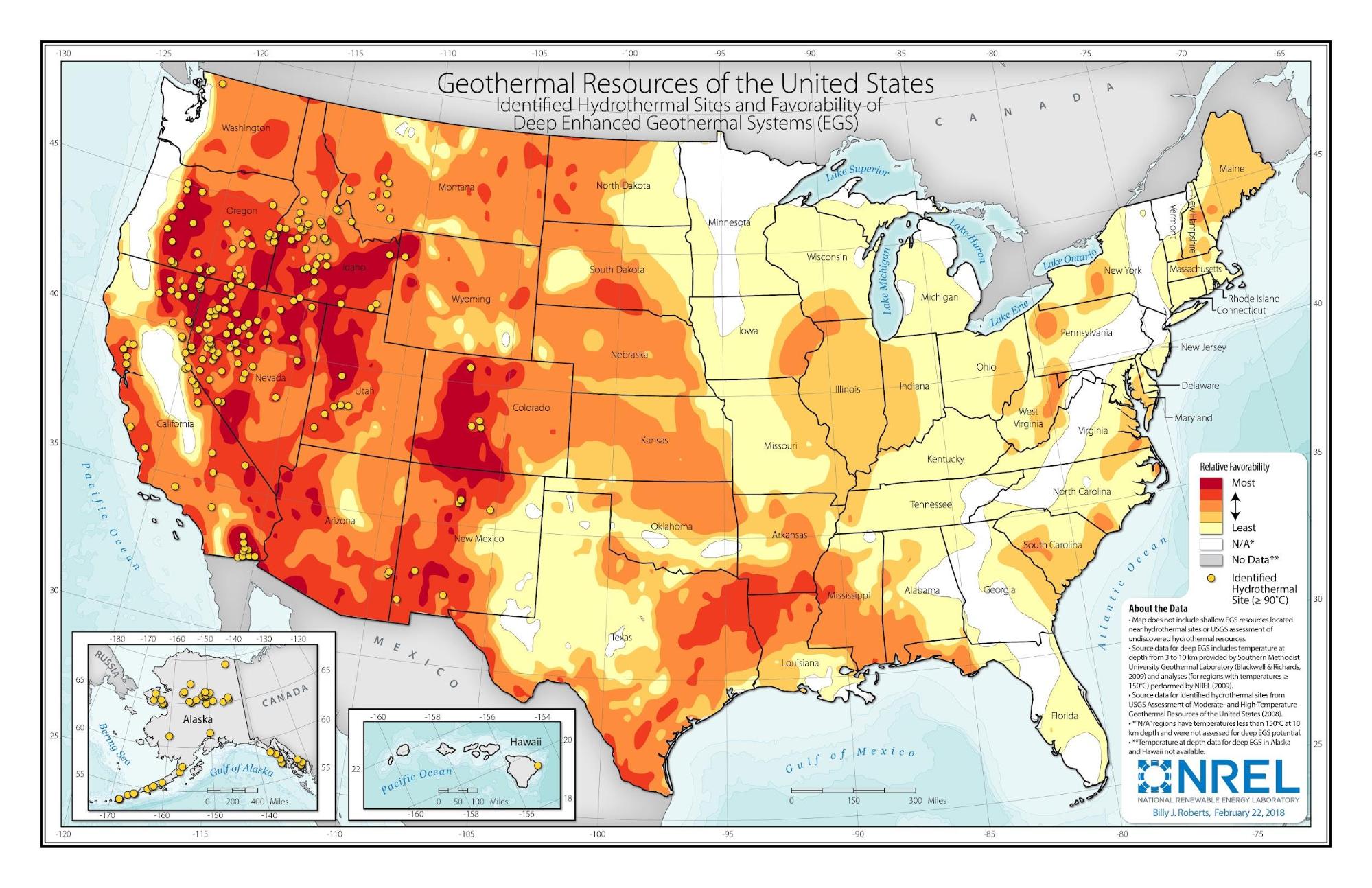

Legacy geothermal systems are costly and rely on existing underground water reservoirs as a heat source, which limits their viability to areas with preexisting geothermal activity and abundant water resources. In contrast, Enhanced Geothermal Systems do not require onsite water supply and can be sited in most areas with sufficient subsurface temperatures. By 2050, the U.S. will require 700-900 GW of additional clean firm energy capacity; EGS has the potential to fill 90 GW of this demand, providing enough power to supply more than 65 million homes. Unlike most renewables, EGS can supply consistent baseload power and heat, and requires a smaller ground footprint than wind and solar. Furthermore, it leverages many existing technologies such as subsurface drilling and hydraulic fracturing used in oil and gas extraction, facilitating rapid rollout and providing career transition prospects for fossil fuel workers. EGS has yet to be implemented at scale, but project costs, drill times, and permitting constraints have all fallen rapidly as interest and investments grow. The Department of Energy’s Pathways to Commercial Liftoff plan advocates for EGS pilot locations in different regions to prove its widespread adaptability; thus far, geothermal projects have mostly been limited to the Basin and Range region in the western U.S., where high subsurface temperatures abound. Nevertheless, DOE’s next pilot funding opportunity will be inclusive of proposals for East Coast sites.

Small EGS pilot projects have been constructed in Massachusetts and Maryland to provide heating and cooling; however, no energy-producing pilot plants have been constructed in the eastern U.S. Although the West contains the majority of viable geothermal sites, the DOE has identified West Virginia and Pennsylvania as highly feasible EGS locations. These states are also known for their outsized roles in producing fossil fuels and exporting energy. Coal remains a core resource in this region; nearly 90% of West Virginia’s electricity is generated using coal (compared to ~7% from renewables), and citizens pay hundreds of millions in subsidies to keep coal plants operational, even as relative costs balloon. Pennsylvania is the nation’s second-largest coal exporter, trailing only West Virginia; renewables produce only 4% of its electricity, excluding its four aging nuclear plants. As fossil fuels face more stringent legislative constraints, these states risk losing their status as energy exporters if they continue to rely on hydrocarbons.

West Virginia and Pennsylvania have something else in common: weak political support for traditional renewables and large energy workforces who remain skeptical of clean energy. From constraining federal clean energy programs to preventing the expansion of solar farms, West Virginia’s political leadership has repeatedly prioritized coal over clean energy. Although coal mining provides tens of thousands of jobs and billions of dollars in export revenue, continued dependence on coal is untenable. Coal’s declining appeal, along with cheaper natural gas and renewables, have diminished the industry’s workforce to its lowest size since 1890, and citizens now pay more for coal power than they would for other energy sources.

Pennsylvania is also no leader on clean energy; between 2013 and 2023, it ranked 49th in the nation in renewable energy growth, trailing behind only Alaska. This is due both to regulatory barriers and the abundant natural gas provided by the Marcellus Shale. New approaches are necessary to enhance the growth of renewables in these states, and the EGS rollout could provide a more politically palatable approach to clean energy.

The White House, along with the DOE, should provide funding from the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL) for three EGS pilot sites in West Virginia and Pennsylvania to be built by 2028. Considering the costs and pace of previous pilot plants, the depth of available thermal resources, and the foreseeable difficulties of EGS expansion in new regions, construction of the pilot plants should receive a budget of roughly $45-60 million. The BIL allocates funds for seven geothermal pilot plants; three pilot projects received such support after applying during the first round of proposals. The second round of prospective grants includes the possibility of Eastern EGS sites, and all efforts should be made to ensure that Appalachian sites are well-represented in the selected proposals. A multi-plant approach also reflects the DOD’s geothermal pilot program, which created sites at several bases in different states using contracts with three EGS companies. Creating multiple pilot plants proves feasibility in different geology and geography, reduces the likelihood of failure, and facilitates wider public and political engagement. Implementation should be coordinated with regional and local grid providers and energy agencies.

Source: NREL. https://www.nrel.gov/gis/assets/images/geothermal-identified-hydrothermal-and-egs.jpg

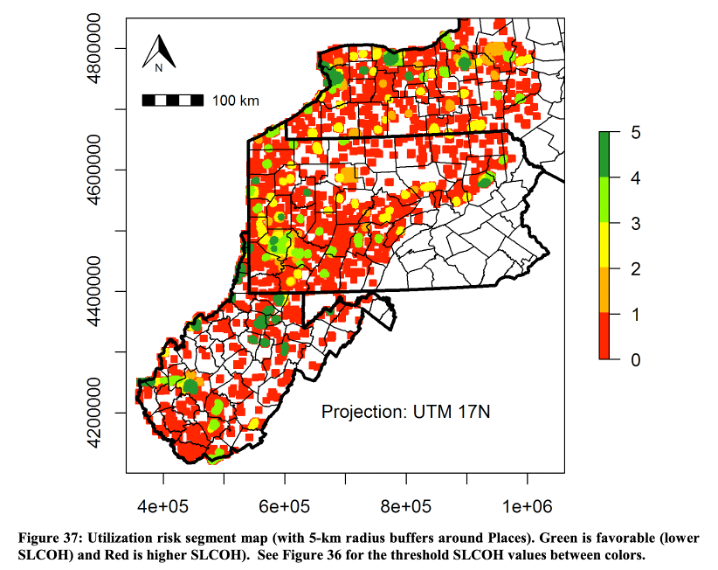

Site selection should be based on several factors: high projected viability and low risk; proximity to existing electrical infrastructure; different geology and geography from existing EGS sites; and political viability. Three potential locations emerge as ideal candidates, given these considerations and in consultation with studies such as the DOE Liftoff plan and other feasibility research. One plant should be sited in northwest Pennsylvania, in order to prove viability in traditional natural gas country, utilize existing gas infrastructure, and facilitate outreach to the gas industry and workforce. Another should be located in northeast Pennsylvania, due to indicated geothermal potential, proximity to larger population centers, and to engage the area’s sizable energy workforce. The final plant should be constructed in northern West Virginia, which offers relatively abundant thermal resources, unique geology with limited natural gas reserves, a declining coal industry, and low support for traditional renewables. Selecting sites for test wells in the vicinity of recently closed coal plants would be ideal, given these locations’ existing transmission infrastructure, energy workforces, and political significance.

In tandem with pilot plant construction, 10-15% of the program’s budget should be allocated to public EGS education and to offer training for local fossil fuel workers. Pennsylvania already uses over 3% of its BIL funds for workforce development; this relatively larger budget to bolster the geothermal workforce reflects the lack of existing EGS plants in the region, as well as additional costs incurred through public education. These funds can be drawn from the initial pilot plant budget or through the $200 million provisioned in BIL for workforce development. This is a vital component of the process; without stakeholder engagement, especially to provide jobs and transparency and engagement for investors, pilot projects lose much of their value. For similar reasons, the program’s contracts and standards should be configured as models for future East Coast EGS projects and risk should be clearly allocated between involved parties.

To minimize negative public reactions towards geothermal, this process should also be intentionally apolitical; investment in renewables can often trigger backlash if it is clearly tied with political interests, especially in conservative states. EGS also has the potential to incur criticisms from environmental groups due to its use of fracking technology. Hopefully, growing support for EGS from mainstream environmental organizations such as the Sierra Club and NRDC will diminish this risk. The NRDC notes, “While this connection (to the oil and gas industry and fracking) may initially give some pause, it creates a fantastic opportunity to deploy an already-trained workforce into an industry that could help secure our zero-emission electricity future.” Given the correct outreach and education strategy that eschews political bias, this campaign can appeal to legacy fuel producers and environmental activists.

Constructing EGS plants in Appalachia, a conservative and renewable-skeptical region with abundant fossil fuels and unique geography, would indicate geothermal’s widespread feasibility. Furthermore, demonstrating the similarities in technology and workforce requirements between geothermal power and fossil fuel industries would engage skeptical audiences and garner broader support for geothermal. EGS plants can make use of the qualified local energy workforces, providing employment and easing implementation. Crucially, funding remains the largest remaining constraint for EGS; the DOE notes that the Eastern geothermal rollout “could have an outsized impact on investor confidence.” Although the declining price of geothermal energy promises to meet DOE’s targets, the U.S. has yet to realize the full geographic potential of EGS. With commercial liftoff planned for 2030, DOE can best position geothermal for success by expanding its reach. The creation of Appalachian EGS facilities could markedly accelerate geothermal’s upscaling, thereby reducing U.S. emissions and facilitating a timely transition to zero-carbon energy.