The Jones Act is costing Americans billions in higher energy costs and delaying the deployment of green energy sources. To address these costs, in addition to the energy supply and environmental consequences of the status quo, lawmakers must reassess the utility of the act.

The Merchant Marine Act of 1920 — commonly called the Jones Act — is an obscure shipping law that requires vessels transporting goods between two U.S. ports be American-made, manned, and flagged. Originally motivated by principles of national security and protectionism, the law was passed to complement a wartime reinvigoration of domestic shipbuilding that saw the U.S. construct one of the most dominant merchant fleets in the world. A century later, however, the Jones Act now presents a major hurdle for domestic offshore energy projects and fuel transportation, resulting in higher energy prices for Americans and slower deployment of cleaner energy sources.

The U.S. offshore wind industry, already plagued by high interest rates, permitting delays, shoddy port infrastructure, supply chain issues, and recent high-profile turbine breakdowns, is desperately searching for ways to improve project costs and expediency. Building offshore wind turbines requires shipping enormous individual components to be assembled on-site, miles from land. In most countries, this is done using specialized vessels called wind turbine installation vessels (WTIVs). With no Jones Act-compliant WTIVs of its own, the U.S. employs smaller compliant vessels instead, which take significantly more trips to and from project sites, raising project costs and emissions. Currently, the U.S. only has one WTIV under construction — Dominion’s Charybdis — which has taken both years and hundreds of millions of dollars to build. Building and deploying Jones Act-compliant WTIVs is far more costly than simply enlisting foreign-owned ones, and that cost is ultimately reflected in project price tags. President Biden’s Bipartisan Infrastructure Law thankfully includes funding for port upgrades which will alleviate some of the infrastructure bottlenecks, but Jones Act reform, in addition to long overdue permitting reform, is essential for scaling offshore wind to meet our energy goals.

The act also has economic and climate implications for LNG markets. The U.S. is a major producer of natural gas, but domestic pipeline infrastructure–particularly in New England–is inadequate to satisfy consumer demand and balance the grid, and attempts to spur new projects are thwarted by neighboring states. This creates a local reliance on shipped LNG to bridge the gap, but foreign-owned vessels bringing gas from the Gulf of Mexico cannot sail to a second U.S. port, necessitating imports from abroad and slowing supply chains in a region where harsh winters make adequate seasonal energy supplies critical. And given New England’s poor electricity and gas pipeline infrastructure, many households there burn extra-dirty fuel oil for home heating that emits more greenhouse gas instead.

Because the U.S. does not possess any of its own Jones Act-compliant LNG tankers, shipped LNG that the Northeast does receive comes from Trinidad and Tobago and other distant countries. These import inefficiencies widen the rift between supply and demand, further inflating already disproportionately-high energy prices for New Englanders. With no foreseeable plans to revamp domestic shipbuilding to produce compliant LNG tankers, the law leaves regions like New England vulnerable to supply chain disruptions and stuck with an expensive and emissions-intensive energy system. These risks, in tandem with energy security concerns spurred by the war in Ukraine, motivated the New England governors to jointly request that the Department of Energy suspend Jones Act restrictions in 2022. A group of New England senators also wrote to DOE about inflated energy prices, citing increased U.S. exports as the cause of supply shortages. In reality, the Jones Act’s shipping rules and disjointed pipeline infrastructure limit supply mobility and leave consumers in the Northeast cut off from the rest of the country’s gas market, beholden instead to exports from abroad and the volatile international LNG trade.

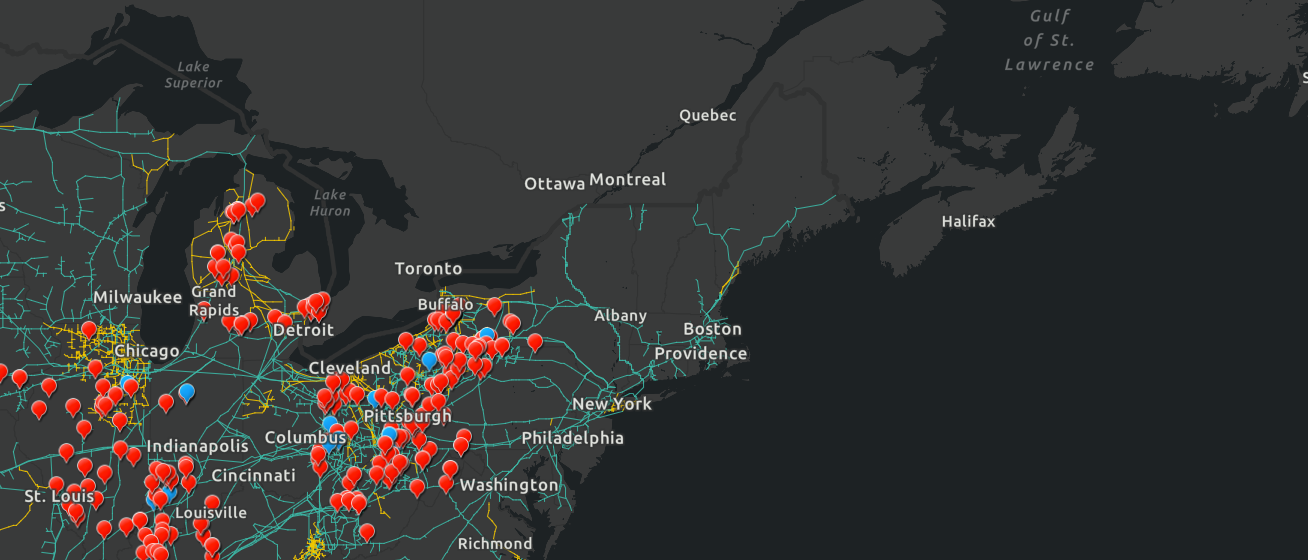

Source: Esri ArcGIS

Energy transportation challenges imposed by the Jones Act also have heightened consequences for Americans outside the mainland. Geographically isolated places such as Alaska, Hawaii, and Puerto Rico are subjected to shipping constraints, cost burdens, and emergency response threats. In fact, the White House had to waive Jones Act requirements for LNG shipments to Puerto Rico in 2022 to enable the territory to recover from devastating hurricanes. And aside from LNG, Jones Act shipping restrictions on petroleum and oil products force Americans to forfeit roughly $769 million in unrealized consumer surplus annually — a conservative estimation which excludes areas with further inflated prices like Alaska, Hawaii, and Puerto Rico.

Ultimately, lawmakers must reassess the utility of the Jones Act. A protectionist law passed in the spirit of national security is no longer doing its job when it poses looming energy and economic concerns, and even stifles the industry it was designed to protect. Its limitations seem especially frivolous considering that the U.S. has no LNG carrier fleet of its own–and a reported 30-year timeline for building one–while countries such as South Korea are already building them more cheaply and efficiently. The lack of compliant LNG and wind turbine installation vessels, in tandem with the eye-popping costs and timelines for building them domestically, make foreign-flagged alternatives a sensible option if we could only use them.

The obvious solution is to repeal the Jones Act, however the political blowback from powerful proponents of domestic industry could be significant — despite the billions of dollars in potential economic output that would follow. At minimum, specific carve-outs or exemptions must be made for foreign specialized energy carriers to promote energy and economic security, particularly in at-risk regions. A large-scale subsidized campaign of domestic shipbuilding could offer another option in theory, but in practice the combination of high costs, fiscal and political uncertainty, existing difficulties with subsidized Navy shipbuilding, and the current availability of non-U.S. ships all strongly suggest that allowing foreign specialized energy vessels to travel between U.S. ports is the best course of action, at least in the short-term.

Until we adopt such reforms, the harmful effects of the outdated Jones Act are a stark reminder that ensuring security and reliability of clean energy–now and in the future–requires a regulatory regime that is not anchored to the past.