2023? United States??

2022 Ghana

2022 Sri Lanka

2022 Russia

2020 Zambia

2020 Argentina

2020 Ecuador

2020 Lebanon

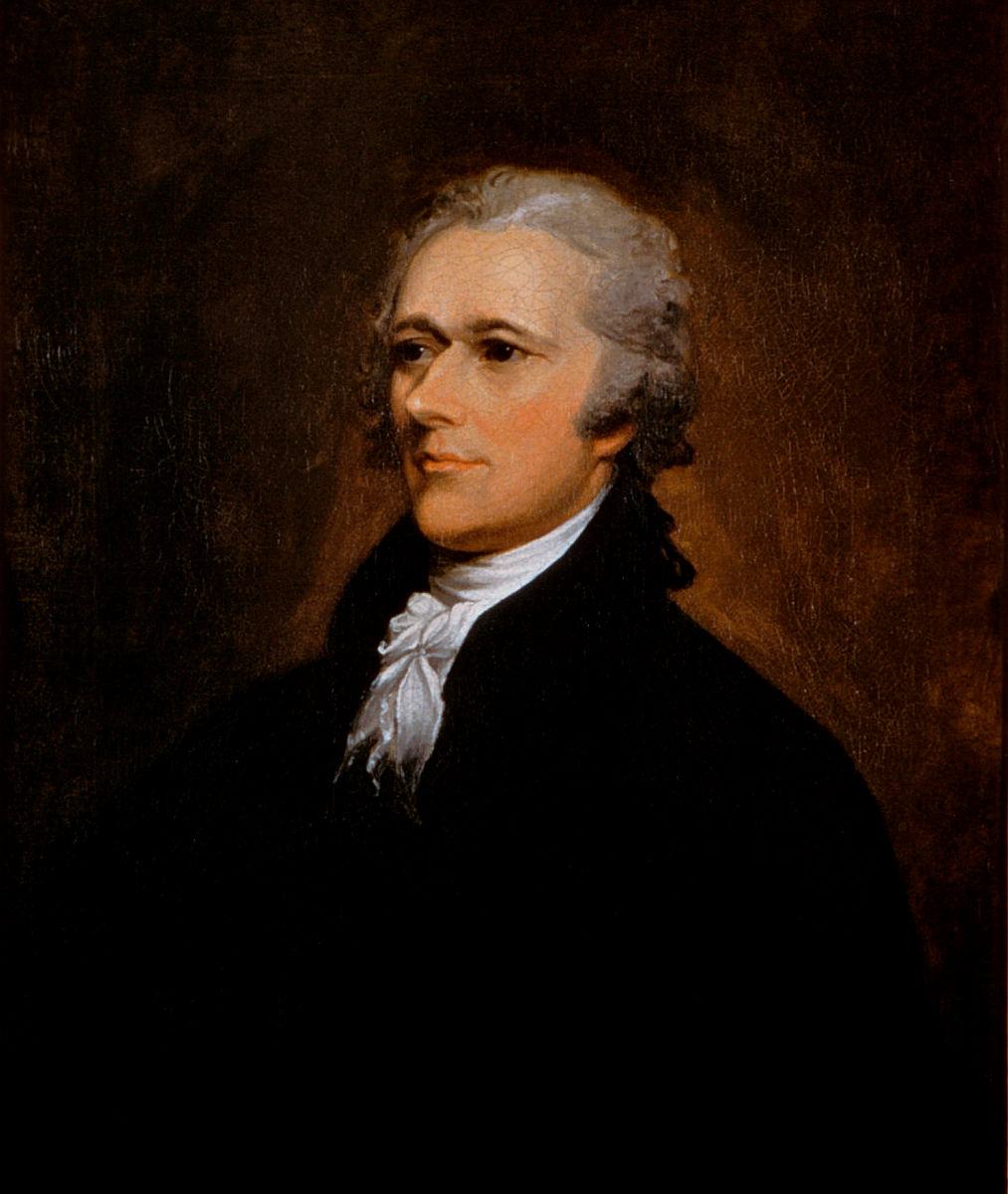

Alexander Hamilton’s Report on Public Credit (January 1790) recommends borrowing for public investment and rigorous commitment to pay the bills. His take on defaults:

“[W]hen the credit of a country is in any degree questionable, it never fails to give an extravagant premium, in one shape or another, upon all the loans it has occasion to make. Nor does the evil end here; the same disadvantage must be sustained upon whatever is to be bought on terms of future payment. From this constant necessity of borrowing and buying dear, it is easy to conceive how immensely the expenses of a nation, in a course of time, will be augmented by an unsound state of the public credit.”

Hamilton’s 77 successors as Treasury Secretary have followed this guidance, paying the bills steadily (with a minor, technical, and instructive exception in 1979) through troubles ranging from the extinction of Hamilton’s Federalist Party in 1808 to the foreign military occupation of Washington in the War of 1812, the Civil War, the Depression, etc. Rogoff & Reinhart list 15 other governments in a relatively small group of never-defaulters: Canada, Denmark, Belgium, Finland, Hong Kong, South Korea, Malaysia, Mauritius, New Zealand, the Netherlands, Norway, Singapore, Switzerland, Thailand, and the United Kingdom.

The post-Hamilton streak is now in some danger, as Congressional Republicans threaten to refuse to raise the U.S.’ “debt ceiling” later this year. This is an accounting device unique to the United States, invented during World War I to avoid separate Congressional votes on every Treasury bond issue; its thesis is that Congress must not only authorize spending and borrowing but later and separately authorize repayment of borrowed money. PPI’s budget and tax director Ben Ritz explains:

“This vote is separate from the decision to set tax and spending policies — raising the debt limit merely allows the Treasury to borrow money to cover the difference between spending and revenue levels as determined by legislation Congress previously enacted.”

What would it mean to go into default? Even the theoretical possibility can be costly: similar threats to block a debt-ceiling increase in 2011 led ratings agency Standard & Poors to cut the U.S.’ credit rating from AAA to AA+, on the grounds that though that summer’s agreement “removed any immediate threat of payment default,” the agreement itself meant that “the statutory debt ceiling and the threat of default have become political bargaining chips in the debate over fiscal policy,” thus making the U.S. less credit-worthy. The U.S. has not since regained its AAA rating. Alternatively, the 1979 event, when the Treasury Department missed an interest payment not deliberately but because its check-writing machines freakishly broke down and took a few hours to fix, led to an 0.6 percent increase in U.S. interest rates lasting almost a year.

Obviously, a deliberate and prolonged default would carry much higher costs. In practical terms, after 23 default-free decades, this week’s ten-year Treasury bonds carry yields of 3.58 percent and U.S. government net interest payments for 2022 were $399 on $30.9 trillion in debt. Analysts guess that each additional interest point would raise U.S. taxpayers’ interest bill by about $180 billion per year, and as one point of reference, Greece’s financial crisis default left the country with a bond yield of 10.14%. Borrowing Hamilton’s vocabulary, this could probably reasonably be termed an “extravagant premium,” an “immense augmentation” of public expense, and an “evil” that would not end quickly.

Nor would interest rates and payments be the only consequence. The International Monetary Fund’s terse summary of Lebanon’s 2022 economic outlook reads “sovereign default in March 2020, followed by a deep recession, a dramatic fall in the value of the Lebanese currency, and triple-digit inflation”. Should the U.S. enter a Lebanon- or Sri Lanka-like situation after a Congressional failure to raise the debt ceiling, the details are unpredictable but the outlook for the domestic economy would be broadly similar, amplified by a potential global financial crisis given the scale of the U.S. economy and the role of Treasury bonds as a foundation of worldwide finance.

With all that in the offing, here is Ritz’s advice for the administration.

Then:

Hamilton’s Report on Public Credit, 1790

Now:

PPI’s Ben Ritz on the debt ceiling, default, and administration options, 2023

The Congressional Budget Office on current debt.

Council of Economic Advisers Chair Cecilia Rouse on the potential consequences of default.

And the International Monetary Fund explains its most recent agreement with post-default Lebanon.

And three perspectives from the 2011 debt-ceiling threats:

Standard & Poors explains the U.S.’ downgrade from AAA to AA+.

The Tax Policy Center’s Donald Marron recalls the unintentional but costly micro-default of 1979.

And former IMF economist Simon Johnson speculates on the gruesome private-sector consequences of a U.S. default. Samples: “A collapse in U.S. Treasury prices … would destroy [private banks’] balance sheets. … There would be a massive run into cash, on an order not seen since the Great Depression … private sector in free fall, consumption, and investment would decline sharply. … [u]nemployment would quickly surpass 20 percent.”) The full text, short but grim.

Ed Gresser is Vice President and Director for Trade and Global Markets at PPI.

Ed returns to PPI after working for the think tank from 2001-2011. He most recently served as the Assistant U.S. Trade Representative for Trade Policy and Economics at the Office of the United States Trade Representative (USTR). In this position, he led USTR’s economic research unit from 2015-2021, and chaired the 21-agency Trade Policy Staff Committee.

Ed began his career on Capitol Hill before serving USTR as Policy Advisor to USTR Charlene Barshefsky from 1998 to 2001. He then led PPI’s Trade and Global Markets Project from 2001 to 2011. After PPI, he co-founded and directed the independent think tank Progressive Economy until rejoining USTR in 2015. In 2013, the Washington International Trade Association presented him with its Lighthouse Award, awarded annually to an individual or group for significant contributions to trade policy.

Ed is the author of Freedom from Want: American Liberalism and the Global Economy (2007). He has published in a variety of journals and newspapers, and his research has been cited by leading academics and international organizations including the WTO, World Bank, and International Monetary Fund. He is a graduate of Stanford University and holds a Master’s Degree in International Affairs from Columbia Universities and a certificate from the Averell Harriman Institute for Advanced Study of the Soviet Union.

Read the full email and sign up for the Trade Fact of the Week