Even before the pandemic, hunger was an intractable problem faced by millions of Americans, and there is a wealth of evidence to support reimagining SNAP by building in more resiliency and making it easier to navigate for both consumers and retailers to strengthen our country’s food system. In this paper, we address recent developments related to SNAP and propose reforms to the program to reduce administrative burdens and churn, ease restrictions on what can be purchased with benefits, make SNAP more resilient for a future crisis as an automatic stabilizer, increase monthly allocations for families with young children, eliminate asset limits, and invest in technologies to increase access and improve participant experience, especially in rural communities. As the Biden administration looks ahead to major public investments, the modernization of SNAP should be included in the American Families Plan.

Last spring, one of the most startling and grim images from the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic were the miles-long lines outside of food banks as the economic toll of the pandemic began to spread across the country. As unemployment rates shot up to levels even higher than during the Great Recession, many families who had never struggled to put food on the table found themselves in desperate need of help.

The sharp rise of hunger during the pandemic would have been immeasurably worse had the Trump administration succeeded in forcing states to impose work requirements on Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) recipients, which would have kicked nearly 700,000 unemployed people out of the program. Fortunately, a federal judge blocked the attempt as “arbitrary and capricious.” The Trump White House also considered new federal requirements to drug test applicants and expand work eligibility — two ways of attempting to push more hungry families off of SNAP.

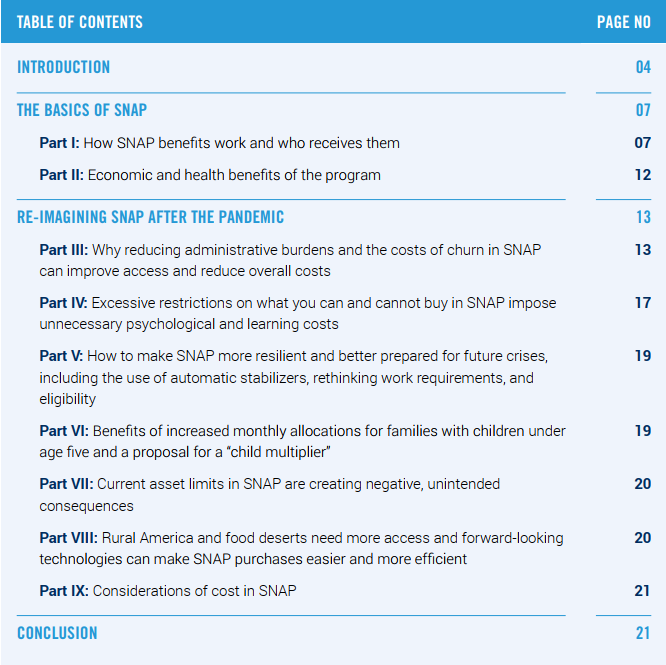

In contrast, President Joe Biden and Congress have made food assistance a top priority, providing aid to hungry families through stimulus and expanded anti-hunger funding, including through SNAP. These efforts have succeeded in reducing historically elevated levels of hunger in America. Recent data released from the U.S. Census Bureau for the end of April 2021 shows that, after multiple rounds of economic aid to struggling families, the percentage of Americans who reported they faced food insecurity was at its lowest point since the pandemic began — at 8.1%.

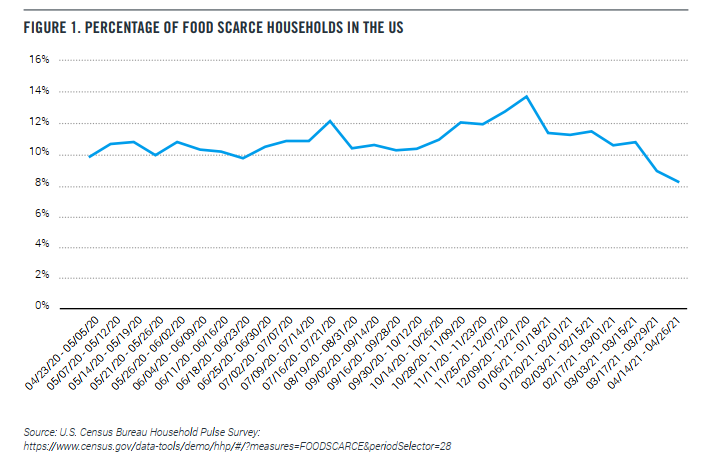

However, even prior to the pandemic, hunger was an urgent problem for many working families, and especially households with children. In 2019, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, as many as 10.5% of households were food insecure at some point during 2019, and that number was even higher for households (13.6%) with children under age 18.

While critical, more money alone won’t end hunger. The pandemic served as a metaphorical earthquake that stress-tested many of our social safety net programs, revealing stark vulnerabilities. SNAP is an essential program that needs to be made more resilient against future public emergencies.

SNAP (formerly known as the Food Stamp Program) is our country’s single most effective and wide-reaching anti-hunger program. It subsidizes food purchases for nearly half of all Americans at some point during their lives and an estimated one in nine Americans in any given month. In 2019 alone, there were 38 million participants who received SNAP benefits in the U.S, and 44% of SNAP recipients are children. The majority of SNAP recipients are also working families with at least one worker, as the program is structured to reward work with increased benefits.

While Republican politicians call for significant cuts to SNAP benefits and giving states more leeway to make it harder for people to apply, Americans broadly recognize the need for food assistance and support SNAP. A 2020 poll conducted by Hunger Free America, a national nonprofit, found that 58% want to increase funding for SNAP, with 32% of that group saying that the money should be boosted significantly. This included support from 40% of Republicans and 75% of Democrats. Historically, domestic hunger has been considered a bipartisan issue, though it has become more partisan over time.

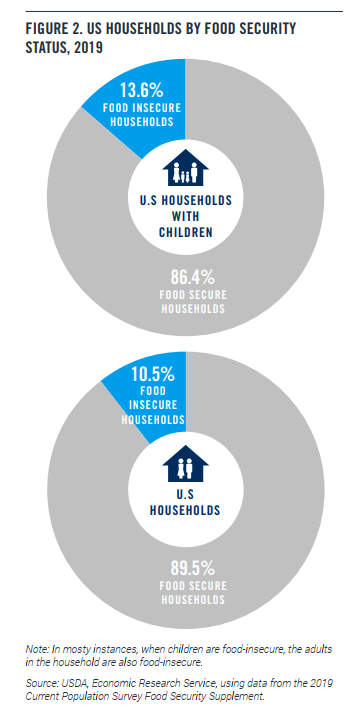

Yet millions of eligible Americans each year do not enroll in SNAP. In 2017, according to the USDA, the take up rate for SNAP was about 84%. Participation rates vary across states, with 52%, in Wyoming, being the lowest. Research suggests that a lack of information, barriers and costs to applying, and stigma around needing food assistance account for most of the gap in participation. For example, in New York City, approximately a quarter of households or

700,000 eligible people do not receive them.

A related challenge is keeping participants in the program. Administrative burdens and inflexibility in recertifying for SNAP benefits increase churn in the program at high costs.

To make it easier and faster to get meals to hungry families during the pandemic, the government relaxed some of the burdensome rules around applying for and retaining food assistance. As enhanced pandemic benefits expire in the coming months, policymakers should act to ensure that SNAP doesn’t revert to the onerous application requirements, poor customer service, and outdated enrollment systems that plagued it in the past. We propose that the Biden administration include the modernization and expansion of SNAP in the American Families package later this year given the state of food insecurity both before and after the pandemic.