Arielle Kane, Director of Health Policy at the Progressive Policy Institute

Charlie Katebi, Health Policy Analyst for Americans for Prosperity

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, few Americans could access telehealth to meet their health care needs. State and national lawmakers imposed enormous obstacles on patients seeking to virtually connect with their health care provider. Policymakers feared widespread telehealth use would increase spending on unnecessary health care services. As such, Medicare banned clinicians from delivering telehealth outside of rural communities and prohibited patients from receiving telehealth within their homes.

But that dynamic changed when the coronavirus pandemic arrived in the United States, shutting down large parts of the economy and forcing families to stay home to reduce the spread of infection. In early 2020, President Donald Trump declared COVID-19 to be a public health emergency and the federal Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) used its emergency powers to temporarily suspend a variety of regulations to allow Medicare recipients to remotely access care through telehealth. In addition, states waived licensing and regulatory barriers to expand access to virtual care for individuals with commercial insurance.

As a result, telehealth became a safe, reliable source of high-quality care for tens of millions of Americans during the pandemic.

Unfortunately, without codifying these temporary reforms into law, they expire at the end of the public health emergency. The pandemic provides an opportunity to study the impact of the increasing use of telehealth services on health care outcomes and costs. Americans for Prosperity and Progressive Policy Institute worked with FAIR Health to examine how telehealth use changed during the pandemic and assess if it had an impact on costs or health outcomes improved.

Using aggregated, de-identified data from FAIR Health, our study found that while telehealth patients’ costs started higher than in-person patients’ costs, the average telehealth patients’ health care costs fell 61%, from $1,099 per month to $425 per month between January 2020 and February 2021.

Additionally, people who used telehealth had lower overall health care utilization compared with people who used only in-person care, except during the early months of the pandemic, March to May 2020.

Our study confirms a promising trend toward cost savings for patients who use a combination of in-person and telehealth services. These results should give lawmakers confidence to extend the telehealth provisions of the public health emergency rather than letting them expire.

There is an axiom in health policy circles: “As Medicare goes, so goes the nation.” Starting in 2001, Congress authorized Medicare to deliver telehealth to the program’s recipients. However, these reforms imposed numerous restrictions that limited the availability of virtual care to a small number of seniors in rural areas. Lawmakers enacted these restrictions because they feared that making telehealth widely accessible would lead to patients accessing unnecessary services. Many clinicians were also hesitant to adopt telehealth, fearing it could disrupt existing practice arrangements and negatively affect their incomes.

But Medicare, insurers, and states shifted their telehealth policies to address COVID-19. On March 13, 2020, President Donald Trump formally declared COVID-19 a national emergency and authorized HHS to temporarily waive laws and regulations to combat and contain the virus. Several days later, Congress passed the CARES Act, which granted HHS additional powers to take emergency measures against COVID-19.

Using its new authority, HHS suspended regulations that prevented health care professionals from remotely delivering care through telehealth. The agency suspended the requirement that Medicare beneficiaries reside in a rural area to receive telehealth services. It waived restrictions that prevented patients from accessing telehealth in their home and allowed for audio-only services. In addition, it permitted rural health clinics (RHCs) and federally qualified health centers (FQHCs) to provide remote virtual care.

HHS also took groundbreaking steps to allow health professionals to deliver a greater array of remote services. The agency announced approximately 240 new telehealth services that providers can deliver to Medicare recipients, including mental health consultations and emergency care.

The agency also authorized all types of health professionals to deliver virtual care to Medicare recipients, expanding the list of telehealth-eligible practitioners to include physical therapists, occupational therapists, and speech language pathologists. Prior to COVID-19, federal law authorized only nine types of health care providers to deliver telehealth services.

Like the federal government, state governors took steps to expand the availability of telehealth to combat COVID-19. Many states suspended regulations that restricted the kinds of technologies practitioners could use to communicate with patients. Ending these restrictions allowed doctors to consult with patients through widely available technology including audio-only phone calls, online video platforms, emails, and instant messages.

Other states waived rules that limited the practice of telehealth to physicians and nurses, expanding practice eligibility to all health care providers licensed by the state. In addition, states removed many rules prohibiting patients from receiving virtual care at home.

Every state also temporarily eased or suspended costly licensing requirements to authorize health care providers licensed in other states to deliver telehealth to their residents. Prior to the pandemic, medical licensing boards charged every license applicant hundreds of dollars and forced them to wait three to nine months before they received a license to practice in their states. These reforms authorized health professionals from all over the country to support patients in pandemic hotspots.

HHS’s emergency actions expanded access to telehealth for Medicare beneficiaries. Before the pandemic, only 134,000 Medicare enrollees received virtual care every week during the first half of 2019. After these reforms took effect, the number of enrollees receiving telehealth increased over 7,400% to 10.1 million between January and June 2020.

These reforms empowered Medicare patients to access telehealth through an array of technology options that were unavailable prior to the pandemic. Because of the availability of audio-only services, the majority (56%) of Medicare beneficiaries who used telehealth did so via phone. Roughly twice the number of Medicare beneficiaries had a telehealth visit via video (28%).

Removing state and federal barriers also expanded telehealth among individuals with commercial health plans. Prior to the public health emergency declaration in January 2020, providers delivered only 1.5% of health services through telehealth, according to claims data compiled by the COVID-19 Health Care Coalition. After these reforms took effect, providers delivered nearly 24% of all services through telehealth.

These telehealth reforms proved to be especially effective at expanding access for patients with complex conditions. Among Americans with private insurance, another study found that the majority of telehealth users used telehealth for chronic conditions, like diabetes, and behavioral conditions, including depression and anxiety. Another study found physical therapy via telehealth after hip surgery was just as clinically effective and less expensive than in-person care.

Overall, consumer interest in telehealth significantly increased during the pandemic. Prior to the pandemic, consumers were also slow to adopt telehealth. Only 11% of patients had a telehealth visit in 2019. By the height of the pandemic, utilization had increased fourfold. But while the pandemic has kickstarted a dramatic shift in health care delivery, a recent survey found that consumers are increasingly frustrated with limits on telehealth services, opaque costs, and confusing technology requirements.

Additionally, even with the expanded coverage, telehealth services are harder to access in rural areas. Rural Medicare beneficiaries reported that their health care providers were less likely to offer telehealth services than those living in urban areas (52% vs. 67%, respectively). And although telehealth seems like it could help expand the services that small rural hospitals could provide, they are the least likely to have the technology because of the upfront costs. The digital divide affects not only patients but also providers.

These groundbreaking telehealth reforms are limited to HHS’ COVID-19 public health emergency declaration in early 2020. As soon as the secretary declares the COVID-19 crisis over, these harmful telehealth barriers will resume and patients will lose access to critical virtual care.

Medicare announced it will no longer offer payment parity for video and telephone visits after the federal public health emergency order expires. When it ends, the Medicare Payment and Access Commission (MedPAC) recommended that “Medicare should return to paying the fee schedule’s facility rate for telehealth services and collect data on the cost of providing these services.”

It also calls for ending providers’ discretion to reduce or waive cost sharing for telehealth services. MedPAC also proposed that CMS permanently establish three safeguards after the public health emergency ends to prevent unnecessary spending and potential fraud from telehealth:

directly

Many states have already reverted to prepandemic telehealth rules. Alaska and Florida have let their public health emergency declarations expire, freezing many telehealth expansions.

However, other states, seeing the value of telehealth, have decided to let telehealth providers keep offering services over the phone pending new federal legislation enabling Medicare to reimburse for a wider spectrum of telehealth services.

Legislative action is necessary to preserve these essential telehealth reforms. To allow Medicare beneficiaries to access telehealth on a long-term basis, Senator Brian Schatz (D-Hawaii) and a bipartisan group of 59 cosponsors introduced the CONNECT For Health Act.

This bill would permanently extend COVID-era telehealth reforms and allow providers to deliver services to Medicare beneficiaries in every ZIP code in the United States, rather than just rural ones. It would also permit Medicare beneficiaries to receive virtual services from the comfort of their home and authorize important facilities such as Federally Qualified Health Centers and Rural Health Centers to deliver telehealth to patients.

Senator Joe Manchin (D-W.Va.) and other lawmakers introduced a similar bill, the Protecting Rural Telehealth Access Act, which would allow providers to offer virtual care to Medicare patients in any area of the country, permit patients to receive telehealth at home, and authorize FQHCs and RHC to provide virtual care. In addition, it would give Medicare beneficiaries the option to consult with health care providers through audio-only phone calls, video messages, and images, which proved popular during the pandemic.

Senator Tim Scott (R-S.C.) introduced the Telehealth Modernization Act to extend telehealth services to Medicare beneficiaries in any geographic area to receive virtual services, including in the home. Furthermore, it would authorize all types of health care providers to deliver virtual care to Medicare recipients. These measures would preserve the important telehealth reforms HHS implemented during the pandemic that allow providers to deliver medically appropriate virtual care.

While many lawmakers are taking steps to permanently enact telehealth reforms into law, some fear that creating new Medicare telehealth benefits will lead to patients spending more taxpayer dollars on health care. Specifically, skeptics cite analysis from the Congressional Budget Office, which estimates removing Medicare’s telehealth limitations on virtual mental health care would increase utilization and thus spending by $1.65 billion over 10 years.

Fortunately, there is mounting evidence that telehealth can lower health care spending and reduce taxpayer costs. According to a 2021 analysis from the MedPAC, when Medicare patients chose telehealth for their primary care needs, in-person primary care visits fell by 25%.

Virtual care can also decrease health care spending by enhancing preventive care and reducing the need for patients to make expensive visits to hospitals and urgent care centers. One 2012 analysis of the Veterans Health Administration’s telehealth program for chronically ill veterans found virtual care reduced the average cost of every patient by $6,500, saving $1 billion in a single year. The program achieved these savings by reducing hospital admissions by 19% and decreasing the number of days patients spend in the hospital by 25%.

As the pandemic drags on, telehealth continues to prove it enhances patient outcomes and lowers costs. In 2020, Ascension Health found 60% of its telehealth patients would have visited an urgent care clinic or emergency room if they did not offer virtual care. This decreased outpatient visits by 33% for Ascension’s patients.

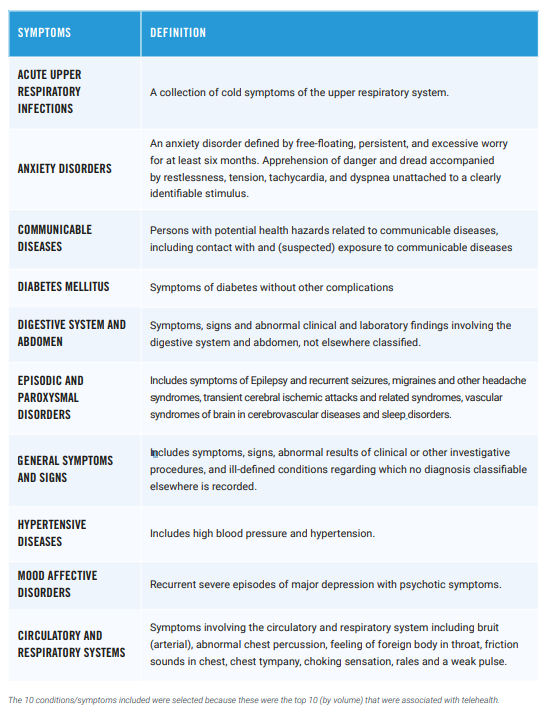

To expand on this evidence, Americans for Prosperity and the Progressive Policy Institute analyzed aggregated, de-identified data provided by FAIR Health, Inc., based on claims data from its FH NPIC® repository of privately insured medical claims. We received statistical results that reflected the experience of patients who received telehealth and those who did not have any telehealth services. The results also included a nationwide study of telehealth’s effect on patient outcomes and health care spending. Americans for Prosperity and Progressive Policy Institute studied the aggregated data results reflecting the claims experience of 8.1 million patients who used telehealth and compared them to an equivalent aggregated dataset which reflected 15.8 million patients who used inperson care only between January 1, 2020, and February 28, 2021.

To determine telehealth’s impact on patient outcomes and costs, we compared data from FAIR Health based on de-identified patients of both groups with the same age, sex, and health conditions. The health conditions included mental disorders, hypertensive diseases, communicable diseases, respiratory infections, circulatory and respiratory symptoms, episodic and paroxysmal disorders, digestive system and abdomen symptoms, and diabetes.

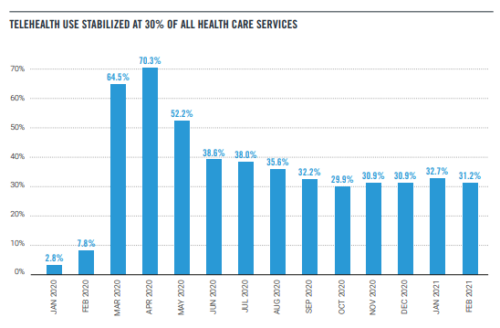

The use of telehealth skyrocketed during the early months of the pandemic. Our study found that in April 2020, telehealth appointments accounted for 70% of all health care appointments.

However, as some of normal life resumed, telehealth appointments stabilized at around 30% of all appointments. Telehealth will never fully replace in-person care, but it’s clear that it can meet patients where they are and help them access needed medical services.

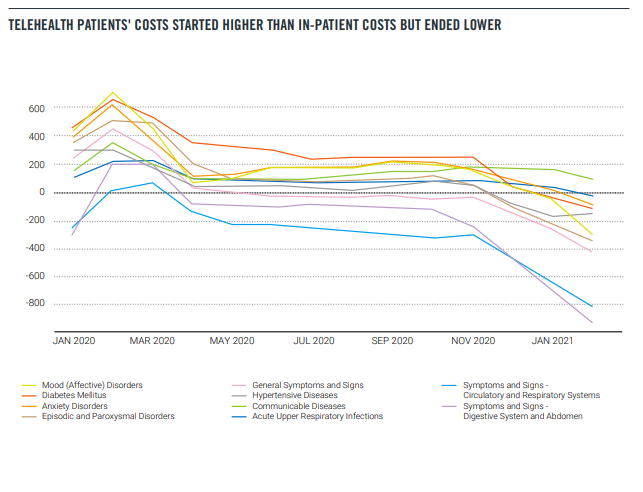

During the pandemic, patients who used telehealth spent more on health services compared with individuals who sought care exclusively from in-person providers. Over the 13-month period studied, individuals who used telehealth spent 19% more on average than in-person patients. This could be explained by the unusual care patterns during the pandemic — sicker patients may have been more afraid of catching COVID-19 and therefore tried to avoid going to the hospital by using telehealth.

Another reason could be policymakers required Medicare, Medicaid, and private health insurers to pay for telehealth services at the same reimbursement rate as in-person services, a policy known as payment parity. Lawmakers intended these measures to encourage providers to offer telehealth as more Americans sought remote care during the pandemic. However, payment parity may have artificially increased the cost of virtual care for patients and taxpayers. Without these expensive mandates, telehealth consultations can cost up to 75% less than in-person consultations. Payment parity may help explain why patients who used telehealth cost more on average than patients who didn’t.

It’s important to note, however, that patients who used telehealth spent significantly less on health services by the end of the study period compared with the start. Between January 2020 and February 2021, the average telehealth users’ monthly health care expenses fell from $1,099 to $425, a 61% decline. Telehealth patients’ costs fell faster than in-person patients: The average in-person patient spent $910 per month in January 2020 and $578 in February 2021.

The data also showed that for seven of the 10 conditions observed, patients who used telehealth spent more than patients who sought in-person care. Only telehealth patients with abdominal symptoms, respiratory symptoms, and general symptoms spent less relative to inperson patients with the same conditions. Again, this could be explained by the unusual care and payment patterns during the pandemic. However, patients of all conditions who used telehealth spent less over time. On a percentage basis, the company found individuals with diabetes, anxiety, and hypertensive diseases had a 71% reduction in spending between January 2020 and February 2021.

Despite the increased availability of telehealth during the pandemic, for the observed conditions, utilization of the health care system did not increase for telehealth users. For seven of the 10 observed conditions, the average number of total appointments with the health care system — one way to measure utilization — was the same or fewer for people who used telehealth relative to people who did not. The only conditions where utilization was higher were anxiety disorders, mood disorders and communicable diseases. This is easily explained by the fact that anxiety and mood disorders require ongoing care and that the study period included a global pandemic and thus appointments related to communicable disease exposure were high.

In the case of emergency department visits, individuals who used telehealth accessed emergency care more often than individuals who used in-person care. During the 13-month study period, 6% of telehealth patients on average visited the ED per month. In contrast, just 3% of in-person patients accessed emergency care over this period.

But the data showed an important trend line: Individuals who used telehealth made significantly fewer emergency room visits at the end of the study period compared to the start. From January 2020 to February 2021, the average telehealth patient saw their monthly ER visit rate fall from 8.5% to 3.03%. These findings confirm prior research that found telehealth allowed providers to deliver early interventions to individuals, resulting in the use of fewer intensive services.

Taken as a whole, our findings offer strong evidence that the rise of telehealth during the pandemic has not increased overall utilization of the health care system, as many policymakers and budget hawks have feared. While some of the findings will need a longer study window to see what happens after the pandemic ends, it’s evident that consumers don’t use telehealth promiscuously. Instead, telehealth presents a promising opportunity to tailor care to individuals’ unique circumstances and makes it easier for people to access essential services.

Our analysis of the aggregated FAIR Health data shows telehealth can dramatically expand health care access without raising costs on taxpayers. Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, state and federal officials implemented groundbreaking temporary reforms that allowed millions of Americans to remotely access essential care from qualified health professionals. As a result, many policymakers propose making long-term reforms to allow providers to deliver telehealth care on a permanent basis. However, some lawmakers fear that making telehealth available would lead to patients spending more on care by making unnecessary purchases of services.

Our analysis of FAIR Health’s data found patients who use telehealth spend significantly less on health care services over time. Between January 2020 and February 2021, the average telehealth patients’ health care expenses fell 61%, from $1,099 per month to $425 per month. Furthermore, telehealth patients purchased fewer in-person health care services such as emergency care during this time period. This suggests virtual care improves patient health and allows individuals to purchase fewer expensive procedures.

These findings hold important lessons for policymakers in Congress and around the country. Our study shows lawmakers can make important telehealth services widely available to families without raising costs on taxpayers. Therefore, Congress should permanently empower health practitioners to provide virtual care to all Medicare recipients. This would ensure seniors continue to receive quality and cost-effective care from the convenience of their homes long after the pandemic ends.

Arielle Kane is the director of Health Policy at the Progressive Policy Institute. Her research focuses on what comes next for health policy in order to expand access, reduce costs and improve quality.

Charlie Katebi is a health policy analyst for Americans for Prosperity, where he promotes state and federal policies that increase patient choices, lower costs, and expand access to quality health care.