| United Arab Emirates | 88% |

| Australia | 28% |

| Canada | 22% |

| Germany | 15% |

| United States | 15% |

| United Kingdom | 13% |

| France | 12% |

| Thailand | 6% |

| Japan | 2% |

| Indonesia | 0.1% |

| China | 0.1% |

In this evening’s Nationals-Braves game, the Nats’ 26-man roster features 10 foreign-born players: four from the Dominican Republic, three from Venezuela, and one each from Panama, Cuba, and Nicaragua. Soto (pictured below), Cruz, Franco, Hernandez, Robles, and Ruiz account for two-thirds of the team’s admittedly modest 50 home runs this year. The visiting Braves have eight international players — Venezuela three, Curacao two, Mexico, Cuba, and the D.R. one each. Both teams pretty well reflect MLB’s overall 28% share of international players. Meanwhile, before and after the game someone has to take care of the grass; while the Nats reasonably decline to publish stats on their groundskeepers, about 33% of all U.S. groundskeepers and building maintenance people are foreign-born. This small window on the U.S.’ immigrant workforce illustrates a sort of national “smile curve,” in which the immigrant workforce is especially large in tough, physical blue-collar work, and also in high-end glamor jobs. More generally:

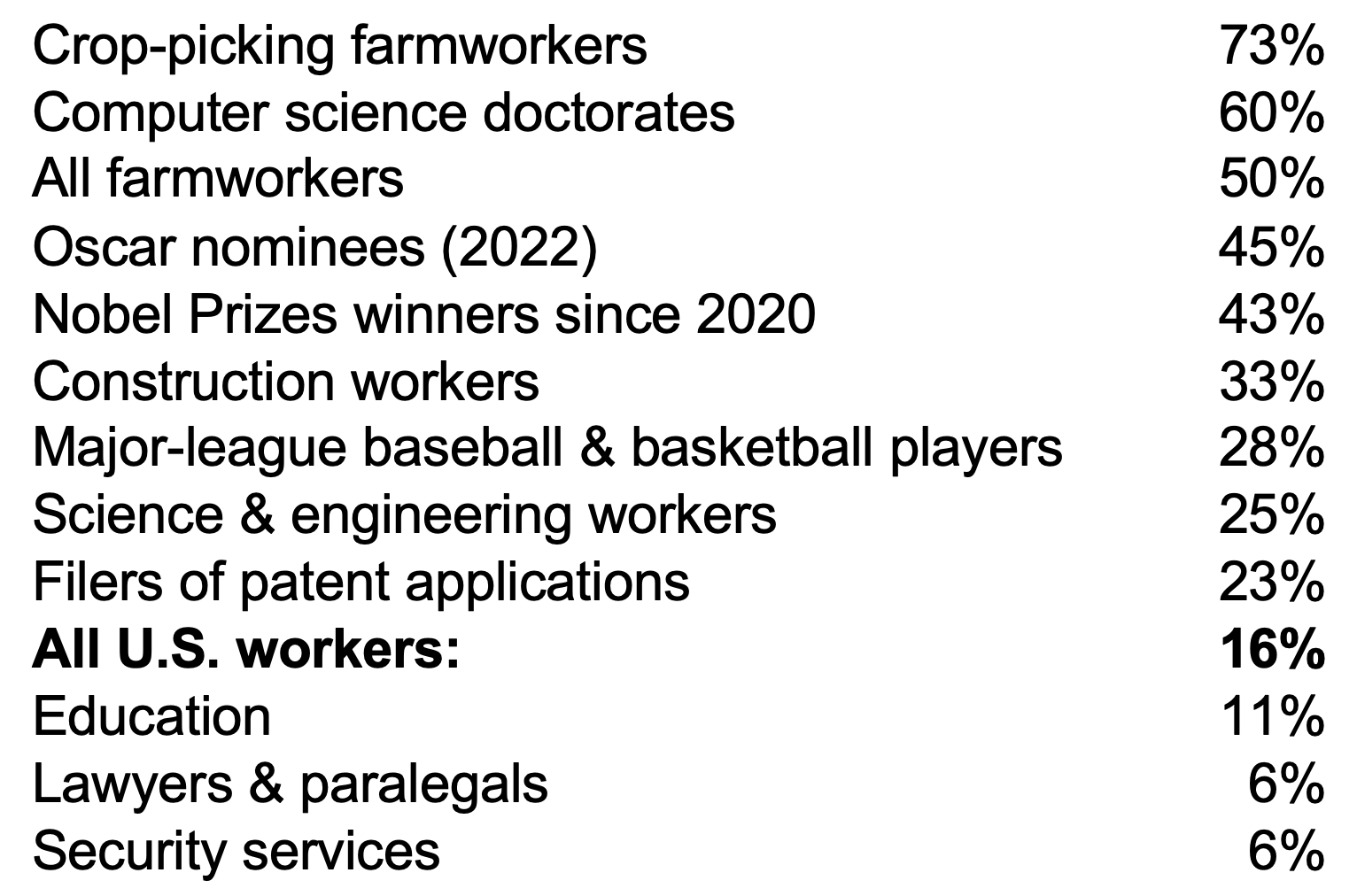

The current edition of the BLS’ Labor Characteristics of the Foreign-Born Workforce, out May 22, found 26.4 million immigrant workers — combining foreign-born U.S. citizens, green card holders, employees on work visas, and undocumented — in the United States as of 2021. Their 17.3% share of America’s 152.6 million employed men and women is high in historical terms – more than triple the 5% of Nixon-era 1970 — though below the 20.5% peak President William Taft’s statisticians recorded in 1910. Definitional differences make the U.S. data hard to compare precisely to experience in other countries, but based on the World Bank’s figures for immigrant shares of population, the U.S. appears (a) far below the majority-immigrant populations of the Persian Gulf, (b) well above the mostly local East Asian workforces, and (c) fairly similar to other large, wealthy western countries. Parsing out BLS’ rather aggregated figures, and adding a few other sources, three particularly international sections of the American workforce are as follows:

Glamor Jobs: A lot of TV and prestige press exposure here. About 28% of major league baseball players and an identical 28% of professional basketball players were born abroad. In Hollywood, 45% of this year’s Oscar acting nominees, using the Best Actor/Actress and Best Supporting Actor/Actress nominations, are either immigrants or temporary visitors; in elite academia and culture, 43% of the U.S.’ Nobel Prize winners since 2000.

Labor-intensive Services: Blue-collar physical work seems very similar to the glamor jobs. At the peak, 50% of hired farmworkers (and 73% of crop pickers) are immigrants, and mostly non-citizens. Construction, and groundskeeping/building maintenance are a tier below, at 33% of construction workers and groundskeepers/building maintenance workers; next come food preparation workers, at 22% of the labor force.

Science and Technology: Immigrants, finally, play an outsize role in American science, technology and innovation. Overall, by the National Science Foundation’s count, 19% of America’s 36 million science and engineering workers, and 23% of the sci/tech workers with bachelor’s degrees and above, are either immigrants or work-visa holders, with India and China the top countries of origin. The peak, above even the farmworker platoons, comes in PhDs in computer science and engineering, where immigrants are respectively 60% and 57% of the workforce.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics’ most recent Labor Characteristics of the Foreign-Born Workforce brief, out May 2022.

And a quick table of the immigrant share of various U.S. occupations:

(Sources: Bureau of Labor Statistics for all workers, National Science Foundation for engineering and science workers; academic paper for patents, and MLB for baseball.)

Some historical data from the Migration Policy Institute.

And a concerned look ahead: Though attempted border crossings draw intense interest, Kansas City Fed researchers believe net immigration to the U.S. has actually dropped sharply since the mid-2010s — from about 1 million per year to 477,000 in 2020 and 245,000 in 2021 — under the combined pressure of COVID-related travel restrictions, reduced granting of work visas, and slower processing of naturalization petitions. Presumably the immigrant share of the workforce has dropped a bit; K.C. Fed staff worry about the implications for innovation, productivity growth, and inflationary pressure.

International perspective

The International Labor Organization counts 169 million “international migrant” workers as of 2019. This meshes imperfectly with the BLS count, as the ILO uses “all foreign-born workers” (including naturalized citizens) for countries which record these figures, but only “migrant” (i.e. non-citizen] workers for some other countries. This noted, the ILO report finds 32% of the world’s migrant workers in Europe, 27% in Canada and the U.S., 15% in the Middle East and 14% in Asia.

Top tier

MLB reports on the “internationally born” players of 2022.

… the Washington Nationals roster, with birthplaces and links to the depressing 2022 pitching and power-hitting stats.

… and a look at Dominican Republic baseball.

The NBA comparison.

Hollywood’s 2022 Oscar nominees.

And the 2021 Nobel Prize winners.

On the land

The USDA on America’s 1.2 million hired farmworkers.

Science and technology

National Science Foundation on the native- and foreign-born sci/tech workforce.

And Stanford researchers Bernstein/Diamond/McQuade/

Ed Gresser is Vice President and Director for Trade and Global Markets at PPI.

Ed returns to PPI after working for the think tank from 2001-2011. He most recently served as the Assistant U.S. Trade Representative for Trade Policy and Economics at the Office of the United States Trade Representative (USTR). In this position, he led USTR’s economic research unit from 2015-2021, and chaired the 21-agency Trade Policy Staff Committee.

Ed began his career on Capitol Hill before serving USTR as Policy Advisor to USTR Charlene Barshefsky from 1998 to 2001. He then led PPI’s Trade and Global Markets Project from 2001 to 2011. After PPI, he co-founded and directed the independent think tank ProgressiveEconomy until rejoining USTR in 2015. In 2013, the Washington International Trade Association presented him with its Lighthouse Award, awarded annually to an individual or group for significant contributions to trade policy.

Ed is the author of Freedom from Want: American Liberalism and the Global Economy (2007). He has published in a variety of journals and newspapers, and his research has been cited by leading academics and international organizations including the WTO, World Bank, and International Monetary Fund. He is a graduate of Stanford University and holds a Master’s Degree in International Affairs from Columbia Universities and a certificate from the Averell Harriman Institute for Advanced Study of the Soviet Union.

Read the full email and sign up for the Trade Fact of the Week