| Current U.S. “MFN” tariff on black and green tea | 0% |

| Current “301” tariff (applied to Chinese tea only) | 7.5% |

| “Tea Act” 1773* | ~8% |

| Trump campaign proposal | 10% |

Parliament intended the “Tea Act” of May 1773 mainly as an emergency bailout of the “East India Company.” In modern terms, the EIC was a “state enterprise” (though one with a military arm) launched in 1600 and, by the late 18th century, governed parts of India. Its conquest of Bengal in the 1760s had left the company nearly bankrupt. To rebuild its finances, the Tea Act authorized the Company to ship a 250-ton stockpile of unwanted tea (bought a year earlier in Guangzhou) to Britain’s Atlantic colonies with the regular 25% export tax waived and a refund for the tariffs it had paid bringing the stockpile into London. The Tea Act left in place an existing 3-pence-per-pound tariff to be paid by colonial buyers, and by requiring export licenses for overseas tea sales, also confirmed that only the EIC was allowed to sell tea to colonial customers. Two often missed details about this very tediously written law:

(1) The 3 pence per pound tea tax wasn’t especially high. Here’s the arithmetic:

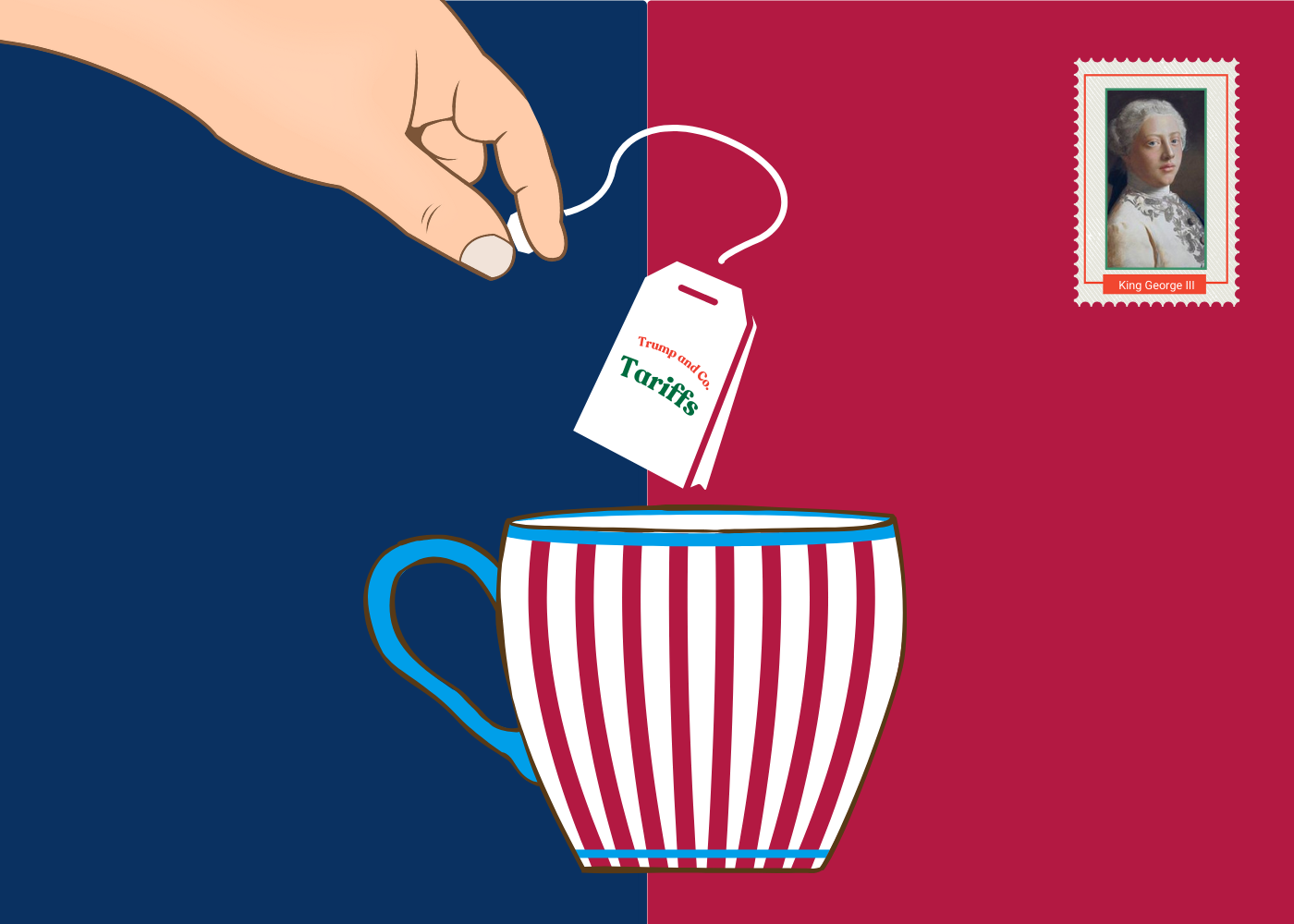

Tea cost 3 to 4 shillings per pound in the 1770s. (Prices varied a bit each year.) In Britain’s confusing 18th-century currency system — golden guineas, pounds sterling, shillings, pence, and farthings — one shilling equaled twelve pence. So “3 pence per pound” meant a tariff varying in a range from about 8% in low-price years to 6% in high-price years. To put this in context, the “301” tariff the Trump administration imposed on Chinese tea in 2019 is 7.5%, essentially identical to the Tea Act level, and the 10% tariff the Trump campaign has pitched is well above the George III rate. (The permanent U.S. tariff on tea is zero for black and green, but 6.4% for some flavored varieties.) Of course, at the time, nobody in Parliament or the Ministry pretended the Chinese tea-growers would somehow pay it; everyone knew colonial consumers would do that.

(2) The tea tax wasn’t new.

Parliament had launched it in 1767 as part of the larger “Townshend Revenue Acts”, which also had imposed tariffs on colonial purchases of molasses, sugar, tea, glass, and some other products. These had all been canceled after colonial protest — no taxation without representation – except for the tea tax. Parliament’s hope in dropping the export tax (apart from rebuilding the EIC’s finances) was that tea prices would fall, inducing the colonists to stop buying tea from other sellers.

Why then did the Tea Act arouse such emotion? Here we can look to the two global-economy grievances cited in the Declaration:

Grievance #16: “For cutting off our trade with all parts of the world” refers most immediately to the blockade of the Port of Boston, begun in mid-1774 in retaliation for the previous December’s Tea Party. (See below for the startling trade data.) The longer-term issue were laws called “Navigation Acts” passed between 1651 and 1696, which (a) banned colonial imports of anything except British-made goods or products such as the EIC tea shipped via British ports, (b) prohibited exports of colonial products to anyone but British buyers, and (c) required use of British-owned ships, with crews of at least 75% British or colonial sailors, to carry goods. The colonists had mostly ignored these rules up to the 1750s, except for the security-sensitive case of timber exports reserved for Royal Navy shipyards. They resented renewed enforcement in the 1760s and 1770s as having financially damaged some of them and eroded everyone’s freedom to buy what they liked, and saw the Tea Act’s attempt to reinforce the EIC’s tea monopoly as escalation.

Grievance #17: “For imposing taxes on us without our consent”, is, of course, the famous “taxation without representation” dispute about the imposition of tariffs (and earlier, stamp taxes) without approval by colonial legislatures. Even at relatively low rates, the Tea Act re-ignited the whole 10-year-old argument by confirming a tax at any level. As with Navigation Act enforcement, the Tea Act’s declaration that Parliament retained its right to impose new ones also seemed to promise lots more to come.

With that, the links between the Declaration’s opening abstract discussion of government principles (“deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed”), the references to specific grievances such as those caused by the Navigation Acts, Tea Act, and Boston Port Act, and the risks the signatories are willing to take to redress them (“we mutually pledge our Lives, our Fortunes, and our sacred Honor”) link up. A bit more below for those interested in whether the tea controversy of 1773 and 1774 has any modern relevance. Either way, PPI trade staff wish readers and friends a happy Fourth.

*By tonnage, Argentina is the top source of U.S. tea at 43 million kilos, or nearly half the 104 million-kilo total in 2023. Traditional growers India, China, Vietnam, and Sri Lanka come next by tonnage; Japan, however, earns the most money selling tea to Americans, with their 3,500 tons of high-end sencha and matcha bringing in $105 million of the U.S.’ $493 million worth of imports last year.

250 years later, is the tea tax controversy relevant for anything but historical interest? If the main question is whether a tax is “legitimately” imposed, here’s the catalogue of current tea policy and proposals:

* The modern zero-tariff rates for black tea and green tea, and the 6.4% for flavored teas, may be good policy or not depending on one’s point of view, but are the result of old tariff bills passed and trade agreements ratified by Congress. So from the ‘representation’ perspective, no problem.

* The 7.5% tariff imposed on Chinese tea during the Trump administration is open to question. It avoided Congressional action and seems at face value in tension with the Constitution’s Article II, Section 8: “Congress shall have power to lay and collect Taxes, Duties, Imposts and Excises.” It still, however, came through a Congressional law (“Section 301”) ceding some Congressional control over tariff policy in cases when administrations want to use tariffs as negotiating leverage.

* The 10% tariff on all tea the campaign has proposed — Sri Lankan, Argentine, Japanese, Chinese, whatever — seems, if imposed by decree, to evade Congressional tax powers altogether.

Data:

Census’ 1975 collection of trade data from the Colonial era and the early republic:

“Cutting off our trade with all countries of the world”: Boston in 1772 — a town of 15,520 by the 1765 census — was getting about 850 ship arrivals a year, and receiving about a fifth of all U.S. trade. After the blockade began this all stopped, and other colonies began refusing British goods in protest. Here are the colonies-UK trade data:

| Colonial exports | Colonial imports

|

|

| 1776 | £0.11 million | £0.06 million |

| 1775 | £1.92 million | £0.19 million |

| 1774 | £1.37 million | £2.59 million |

| 1773 | £1.37 million | £2.08 million

|

Background and documents:

The U.S. National Archives’ official text of the Declaration.

… and discussion from the Monticello Foundation.

The UK National Archives explains 18th-century British currency (four farthings per pence, 12 pence per shilling, 20 shillings per pound sterling, and 21 shillings per golden guinea).

… and reprints British government reaction to the Tea Party.

… and Yale Law School reprints the text of the verbose Boston Port Act which followed.

And a book recommendation:

The Smithsonian’s essay collection The American Revolution: A World War looks at the Revolution from abroad, with appearances by French admirals, Chinese tea merchants, Spanish viceroys, German warlords, Dutch gun-runners, and the intrepid Sultan Haidar Ali of Mysore, admired by the colonists as a fellow enemy of the East India Company and namesake of one of the Continental Navy’s 65 ships, the 40-ton Hyder-Ally.

Ed Gresser is Vice President and Director for Trade and Global Markets at PPI.

Ed returns to PPI after working for the think tank from 2001-2011. He most recently served as the Assistant U.S. Trade Representative for Trade Policy and Economics at the Office of the United States Trade Representative (USTR). In this position, he led USTR’s economic research unit from 2015-2021, and chaired the 21-agency Trade Policy Staff Committee.

Ed began his career on Capitol Hill before serving USTR as Policy Advisor to USTR Charlene Barshefsky from 1998 to 2001. He then led PPI’s Trade and Global Markets Project from 2001 to 2011. After PPI, he co-founded and directed the independent think tank ProgressiveEconomy until rejoining USTR in 2015. In 2013, the Washington International Trade Association presented him with its Lighthouse Award, awarded annually to an individual or group for significant contributions to trade policy.

Ed is the author of Freedom from Want: American Liberalism and the Global Economy (2007). He has published in a variety of journals and newspapers, and his research has been cited by leading academics and international organizations including the WTO, World Bank, and International Monetary Fund. He is a graduate of Stanford University and holds a Master’s Degree in International Affairs from Columbia Universities and a certificate from the Averell Harriman Institute for Advanced Study of the Soviet Union.