President Biden’s American Jobs Plan proposed to spend $300 billion on rebuilding America’s manufacturing sector. The funds would be distributed through a variety of channels, including $50 billion in semiconductor manufacturing and research, $50 billion for a new office to fund investments to support production of critical goods. Biden also called for the creation of a “new financing program to support debt and equity investments for manufacturing to strengthen the resilience of America’s supply chains.”

The US Innovation and Competition Act of 2021, which passed the Senate in early June, also highlights pro-manufacturing polices. These include funding for semiconductor manufacturing and research, money for regional technology hubs, and the creation of the position of Chief Manufacturing Officer in the White House to coordinate the nation’s manufacturing policies.

We believe that these plans are a big step in the right direction, and applaud the President’s and the Senate’s focus on manufacturing. But the nation’s policy framework for manufacturing needs more explicit emphasis on digitization of physical production, which is the only way that American manufacturers can compete over the long run and create new jobs. In addition, the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) introduced an odd quirk into the business tax code that will make it more expensive for some manufacturers to borrow. That quirk needs to be fixed.

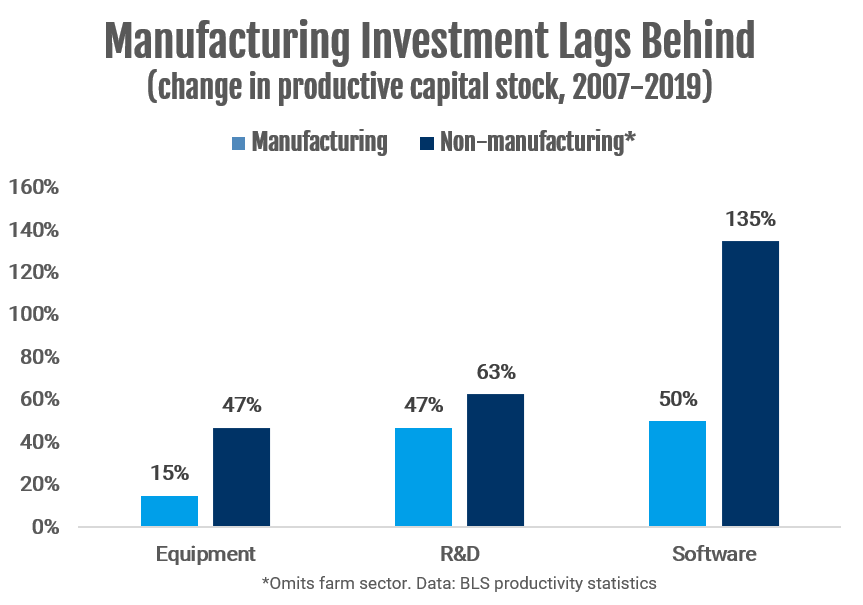

First, we review the facts about manufacturing investment. Government figures show that domestic investment by manufacturers has been lagging the rest of the economy by a substantial margin. During the last business cycle—which started in 2007 and ended in 2019—the productive stock of equipment rose by 15% in the manufacturing sector, far less than the 47% increase in the rest of the non-farm business sector (see chart below). (Equipment includes everything from industrial machinery to trucks to computers and communications gear bought by manufacturers).

This weakness in factory investment undermines the usual argument that manufacturing workers have been mainly displaced by automation. Certainly automation has been progressing, but if capital investment in robots and the like were the main cause of job loss, the investment surge in equipment would have been much bigger. The White House 100-day supply chain review points out that “many SME manufacturers are underinvesting in new technology to increase their productivity.” Contrast this with the warehousing industry (including fulfillment centers) where the productive stock of equipment rose by 91% from 2007 to 2019, even as employment soared.

Moreover, manufacturers have been lagging in software and R&D investment as well. The productive stock of software in the manufacturing sector rose by 50 percent from 2007 to 2019, compared to a 135 percent increase in the non-manufacturing sector. The productive stock of research and development rose by 47 percent in the manufacturing sector, compared to a 63 percent increase in the non-manufacturing sector.

The investment picture gets even worse when we look at specific industries within manufacturing. Consider the computer and electronics products industry, which includes semiconductor manufacturing. The productive stock of equipment in this industry did not grow at all from 2007 to 2019, and similarly for the stock of software. In other words, the computer and electronics product industry, including semiconductors, had no net investment in equipment and software over this 12-year stretch. This may help explain why government action to boost semiconductor manufacturing investment is necessary now.

Similarly, capital investment in the motor vehicle industry has been lagging. The 22 percent increase in the productive stock of equipment (including robots) is above the norm for manufacturing, but well behind the average for the nonmanufacturing sector. And investment in motor vehicle R&D, while still strong in absolute terms, has barely kept up with the industry’s need to shift to electric vehicles. Once again, the investment data helps us identify manufacturing sectors that need help in competing with China.

We note that the manufacturing sector is responsible for the entire slowdown in equipment investment compared to the 1990s. That shows how important it is that the U.S. address the issue of weakness in investment in manufacturing.

So what can we do? Biden’s manufacturing plan and the Competition and Innovation Act passed by the Senate are both heading in the right direction, but they could be improved with an overarching vision. As PPI has noted in several reports, we need the American manufacturing industry to invest in digitization—not just robots on the factory floor, but manufacturing platforms that make it easier for American startups to join global supply chains. The Biden Administration should think in terms of an Internet of Goods, where manufacturers plug into a network of companies that are linked digitally. The Biden manufacturing initiative should build on existing platforms such as Xometry and Fictiv to connect smaller suppliers.

The other big issue is funding. Manufacturing requires large capital investments, so borrowing costs are always a consideration. Unfortunately, in an example of the law of unforeseen consequences, key provisions of the 2017 TCJA are about to make it much more expensive for manufacturers and other capital-heavy businesses to fund their investments, even before any potential increase in the corporate income tax rate.

First, the TCJA permitted full expensing for investments in short-lived assets such as machinery and equipment. However, the “bonus depreciation” will begin phasing out in 2023 and will be eliminated by 2027. That will make it more expensive for manufacturing investment.

Second, the TCJA reduced the amount of interest expenses that most businesses could deduct from 50 percent to 30 percent of a business’s “earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization” (EBITDA). Because of the pandemic, the CARES Act temporarily relaxed this restriction for 2020, but it comes back into effect for 2021.

Third, as of 2022, the TCJA further reduces the tax deductibility of interest to 30 percent of business “earnings before interest and tax” (EBIT). The difference between EBIT and EIBTDA is depreciation and amortization, which can be enormous for asset-heavy manufacturers. This 2022 shift, as embodied in current law, will have the effect of reducing the amount of interest that a manufacturer or other investment-heavy company can deduct.

To understand the magnitude of this change, consider American Axle & Manufacturing, a leading automotive supplier that did $4.7 billion in sales in 2020. The company’s EBITDA was $720 million, and depreciation and amortization was $522 million. That means EBIT was only $188 million (Note: These numbers are all drawn from the company’s public 10K, with no contact with the company).

In 2020 American Axle paid $212 million in interest. Under the TCJA rules that apply to 2021, it would all be deductible, since $212 million is less than 30 percent of $720 million. Under the TCJA rules that apply to 2022 and after, assuming that all numbers remain the same, only $56 million of the interest payment will be deductible. Future borrowing will take the same hit.

When the TCJA was passed, the increased restrictions on the deductibility of interest seemed appealing to many policymakers for several reasons. First, it reduced the bias in the tax code toward debt financing. Second, it discouraged excess borrowing by companies. Third, it raised money and helped balance out the cost of cutting corporate income tax rates.

However, the increased restrictions are likely to disproportionately affect manufacturers, who as a whole paid $96 billion and $90 billion in interest in 2018 and 2019 respectively, more than any other sector of the economy except real estate (who could opt out of the new requirements). The impact of this provision on companies like American Axle will be even greater if interest rates rise, as seems likely.

Given the acknowledged importance of manufacturing, it might make sense for lawmakers to consider extending the provision of the CARES Act that relaxes the limitations on interest expense deductions to avoid imposing another financial burden on the U.S. manufacturing sector. This would also cover the coming shift to EBIT. Such a move might be especially appropriate if the current provisions of the tax law that phase out bonus depreciation stay in effect. If we care about domestic factory investment, it seems like a mistake to make it more expensive for manufacturers to borrow even while the depreciation rules become more restrictive.