issue: Health Care

Protections for pregnant workers is a small change with big rewards

The House of Representatives recently passed the Pregnant Workers Fairness Act (PWFA) which would require that most employers provide reasonable accommodations for pregnant employees – similar to what is required by the Americans with Disabilities Act.

This bill is a sliver of good news for women who have disproportionately born the brunt of this pandemic. Not only do women work in industries more likely to be affected by Covid-19 (health care, direct care, and a slew of service industries) they are also bearing the brunt of the economic implications of the pandemic.

Just last week, the new jobs report, released by the Labor Department showed that without schools and child care, women are dropping out of the workforce in record numbers. Of the 1.1 million adults who reported leaving the workforce (not working or looking for work) between August and September, more than 800,000 were women. For comparison, 216,000 men left the job market over same time period.

Without safely opening schools and child care centers, or closing the gender wage gap, it’s hard to see what other options women have.

But the good news is, that if this law passes the Senate, pregnant women may get better accommodation which could protect them and their babies.

Current federal law protects pregnant employees from discrimination but there is no law that requires pregnant workers receive reasonable accommodation to continue working without jeopardizing their pregnancy. Reasonable accommodation could be reassigning tasks or maybe more flexible work schedules, allowing more work from home hours when appropriate. We’ve learned from Covid-19, that working from home does not necessarily mean less productivity.

While it’s premature to fully understand the effects of Covid-19 on pregnancy, a few trends have emerged:

- Covid-19 infection is associated with premature birth: While the data is premature and limited, some studies are linking preterm with Covid-19. If this trend continues, it will be even more important to provide working pregnant women with accommodations to reduce their likelihood of contracting the virus.

- Sheltering in place, reduced premature birth: There is some good news for pregnant women: Across countries with strict lockdowns or shelter-in-place orders from the pandemic, premature births fell. In Denmark, premature births fell by 90 percent and in Ireland, babies with very low birth weight fell by 73 percent. Doctors are still trying to understand why – less pollution, travel, infection or hustle and bustle could all help explain the decline.

These two points illustrate that reasonable accommodation to either avoid infections or reduce unnecessary stress could have a dramatic impact on working women and their babies. If it signed into law, the PWFA would:

- Require public employers and private employers with 15+ employees make reasonable accommodations for pregnant workers and job applicants as long as it does not create undue hardship on the employer

- Allow pregnant employees to request accommodation without retaliation

The bill has the support of the business community, civil rights groups, and labor advocacy organizations.

At a time when women are disproportionately impacted from this virus, this bill is a small victory to families across the country and the Senate should pass it expediently.

This blog was also published on Medium.com.

A Rare Sign of Bipartisanship Progress: Telehealth in America

Over the August recess, I published a paper with Americans For Prosperity (shocking, I know) to highlight where there is bipartisan consensus on telehealth. Since the pandemic began, many telehealth regulations have been lifted and we explained what changes should be made permanent, what changes should go, and what additional policies could make care easier to access remotely.

Sen. Brian Schatz said that our paper demonstrated that, “telehealth is a rare area with strong bipartisan support and it’s here to stay. While we have made some progress in Congress on expanding access to telehealth during this pandemic, we have more work to do to make these changes permanent and allow more patients to continue receiving the critical health care they need wherever they are.”

I’ve summarized the findings on Medium.

We should push for more progress in telehealth

Over the last few months, millions of Americans have used telehealth services — the remote delivery of care and health monitoring using digital telecommunications tools — to get health care. Federal and state policymakers have made it easier to access telehealth during the pandemic to keep people home and safe but there is no reason to slow the momentum after so much progress has been made.

Due to policy changes at the state and federal levels, the use of telehealth has grown faster in the past five months than in the preceding 25 years. During the COVID-19 pandemic:

-

Nearly one in two consumers have used telehealth to replace a canceled in-person appointment

-

More than 11.3 million Medicare enrollees accessed care from the comfort and safety of their own homes

-

The Veterans Administration provided 1.1 million telehealth visits for veterans

Most of the current telehealth expansions are temporary and will expire with the end of the current public health emergency declaration. But they don’t need to. In fact, 39 senators from both sides of the aisle have introduced legislation that would make some of those changes permanent.

Read the full op-ed here.

New Report Calls on Congress to Make Telehealth Reforms Permanent, Applauded by Bipartisan Pair of U.S. Senators

Contact: Carter Christensen, cchristensen@ppionline.org

WASHINGTON, D.C. – The Progressive Policy Institute (PPI) has released a new white paper in partnership with Americans for Prosperity (AFP), calling on Congress to make telehealth reforms permanent amid and after the COVID-19 emergency — an unlikely partnership in a time of great need for innovation and leadership.

A bipartisan pair of Senators shared support of the findings of the new report — Sen. Roger Wicker (R-MS) and Sen. Brian Schatz (D-HI), have worked across party lines to advance telehealth across the country.

Sen. Brian Schatz (D-HI) said, “As this paper shows, telehealth is a rare area with strong bipartisan support and it’s here to stay. While we have made some progress in Congress on expanding access to telehealth during this pandemic, we have more work to do to make these changes permanent and allow more patients to continue receiving the critical health care they need wherever they are.”

Sen. Roger Wicker (R-MS) said, “It is refreshing to see two groups with such different perspectives come together to support greater access to telehealth. When Senator Schatz and I started our telehealth working group years ago, we chose to work on bipartisan policy that would improve access to health care and save lives. We will continue to work together to ensure Americans can enjoy the benefits of telehealth for years to come.”

Numerous citizen organizations are urging congressional leaders to make other temporary Medicare telehealth changes permanent, as are a growing number of lawmakers – including a bipartisan group of 29 U.S. senators.15 Meanwhile, numerous lawmakers have introduced legislation, including the bipartisan CONNECT for Health Act, which would grant CMS standing authority to make a number of positive changes on a permanent basis.16

Here are the specific policies that AFP and PPI recommend Congress make permanent:

• Continue allowing patients to use telehealth outside of rural areas and at home.

• Continue allowing providers to deliver care to both established and new patients.

• Continue allowing licensed providers to practice across state lines.

• Continue allowing health care providers to use store-and-forward technologies where medically appropriate.

• Do not impose payment parity for telehealth services versus those provided in person.

The Promise of Telehealth Beyond the Emergency

In the past few months, millions of Americans have experienced a first, tantalizing glimpse of the promise of telehealth.1

The use of telehealth – the remote delivery of care and monitoring of patients’ health using digital telecommunications tools – has surged during the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic, as policymakers and insurers across the country have eased restrictions on these tools in order to slow the spread of the novel coronavirus, for which humans have no immunity. Digital encounters can help people avoid unnecessary in-person contacts and receive care at home instead of a potentially overwhelmed hospital or clinic.

As a result of numerous policy changes at the state and federal levels, the use of telehealth has grown faster in the past five months than in the preceding 25 years. During this time:

• Nationally, nearly one in two consumers have used telehealth to replace a cancelled in-person appointment.2

• More than 11.3 million Medicare enrollees have accessed care from the comfort and safety of their own homes, up from nearly zero the year before.3

• American veterans have availed themselves of 1.1 million telehealth visits through the Veterans Administration.4

Most of the current telehealth expansions are temporary and will expire with the end of the current public health emergency declaration.5 A key question arises: Should the reforms be made permanent?

Although our two organizations differ on many health policy issues, on this question we agree. The current, temporary telehealth reforms are good for patients and should be made permanent.

In this paper, we will explain why we think telehealth is valuable and give a high-level overview of the recent policy changes. We’ll also explain why the adoption of telehealth has been slow until now and identify reforms we believe should be made permanent. Finally, we’ll recommend additional policy changes that could help further promote the promise of telehealth. Our hope is that our writing this paper together will persuade state and federal policymakers to make that promise a reality for patients.

SECTION 01

Why is telehealth valuable?

Telehealth can save time, money, and most importantly lives. Studies show that digitally delivered care typically costs only about half of the cost of services provided in doctors’ offices and urgent care clinics6 and can dramatically reduce unnecessary emergency room trips for patients with chronic conditions.7

On a more personal level, the promise of telehealth takes many forms. To access health care conveniently from the comfort of home, for example, or to have one’s vital signs monitored remotely in real time, to check in with a doctor or nurse with a question without having to take time off work, or to send a photo or email to your doctor for review and go on about your business – these are just some of the ways in which modern telecommunications tools can make life better for people.

Real-time forms of care, such as two-way video, can obviously help slow a contagion by reducing personal contact. But asynchronous forms of care, such as recorded video and so-called store-and-forward systems, can also be very helpful, especially when a matter is non-urgent. For example, in ophthalmology, people may have a question about a prescription lens renewal. Or in dermatology, they might want to have a rash or mole examined at the provider’s convenience.

The real question is not whether telehealth is valuable, but why it isn’t already a standard feature of modern medicine.

SECTION 02

Why has telehealth adoption been slow until now?

Until this year, America has been slow to adopt telehealth. Although private payers have been quicker than public payers to cover telehealth services, overall adoption has been modest. Why? Primarily because of barriers erected by various stakeholders, often in the name of assuring quality and safety for patients. This has been done despite a growing body of evidence that telehealth improves clinical outcomes.8

For example, the substitution of digital tools for in-person care has long faced skepticism from private insurers and Medicare, as well as some state regulators, who fear widespread adoption will lead to overutilization and fraud. Some physician groups, too, have feared it could disrupt existing practice patterns and have a negative effect on their members’ incomes.

At the same time, state professional licensure laws have limited the provision of remote care by health professionals licensed out-of-state.

Admittedly, until this year patients do not seem to have been clamoring for access to telehealth. But with the pandemic, that appears to be changing. While an April 2020 survey found that just 32 percent of Americans had ever used a telehealth service, by May that number had risen to 44 percent, with 80 percent of Americans agreeing with the statement that Covid-19 had made telehealth “an indispensable part” of the healthcare system.9 Sixty-five percent said they believe they will use telehealth services after the pandemic is over.10

SECTION 03

What policy changes have been made in recent months?

Federal Actions: In non-emergency times, Medicare’s ability to expand coverage to telehealth is quite limited. Services may only originate from inside an officially designated rural health professional shortage area, and from a statutorily allowed setting, which with very limited exceptions does not include the patient’s home. There are rules limiting what types of providers may deliver telehealth services, and requiring that telehealth be delivered by a real-time, two-way, audio-video connection. Other technologies, such as audio-only telephone calls and secure private emails, are not covered. Neither are asynchronous (store-and-forward) tools or remote monitoring of patients’ vital signs. On top of all this, the patient must have a prior existing relationship with the provider before he or she can use telehealth with that provider.11

In late January of this year, after the federal Department of Health and Human Services officially declared the spread of Covid-19 to be a public health emergency and Congress provided authority to waive statutory restrictions on telehealth during the pandemic, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) used those emergency powers to dramatically expand the telehealth services covered by Medicare and the digital platforms that may be used to provide care via telehealth. The agency also increased the amounts paid for telehealth visits and allowed providers to bill for services provided across state lines. Medicare officials also doubled the list of telehealth-provided services that Medicare will cover, including therapy services, emergency department visits, initial nursing facility and discharge visits, and home visits outside of rural shortage areas.12

Under the CARES Act, Congress liberalized the statute governing health savings accounts (HSAs) to allow patients to receive first-dollar coverage of telehealth services (meaning without having to first meet a deductible) through the end of 2021.13

State actions: Prior to the pandemic, almost all state Medicaid programs covered some telehealth services provided via live video; otherwise, state laws on telehealth varied dramatically. When the pandemic struck, all states eased at least some restrictions on telehealth, and 48 of them temporarily reduced some or all of their licensing requirements for out-of-state health care providers, making it easier for providers to treat patients across state lines. A couple of noteworthy examples: 1) Maryland expanded the state’s definition of telehealth to include audio-only and store-and-forward technology – affecting all payers in the state, not just the Medicaid program. 2) New Hampshire permanently expanded telehealth benefits to all of its Medicaid recipients, not just underserved communities as had been allowed previously, and removed location limits on providers.

Private payer actions: Many private insurers increased their coverage and reimbursement rates for telehealth services. Humana, for example, is waiving all copays for tele-primary care and tele-behavioral health visits for its Medicare Advantage members. Furthermore, many private health plans are voluntarily mirroring the government’s policies, or even going beyond them. Some states (California, for example) are pressuring private insurers to expand telehealth coverage, while others require them to do so.

Provider actions: Doctors and hospitals that have not previously offered telehealth services have been scrambling to adapt, both to make up for lost revenue as elective procedures have been put on hold and to safely maintain patient care. And some providers are restructuring their business models to make telehealth a permanent option for patients who pay out-ofpocket rather than through insurance.

SECTION 04

Which policy changes should remain in place?

As we’ve said, most of the recent policy changes are temporary. In light of the experience of the past few months, and the benefit to patients, it would be exceedingly odd to go back to the pre-Covid status quo. Happily, a consensus seems to be forming in favor of making those gains permanent. The Medicare agency has recently announced that it will make its newly added telehealth codes permanent, something it has the power to do under existing law, separate and apart from its temporary emergency powers.14 And numerous citizen organizations are urging congressional leaders to make other temporary Medicare telehealth changes permanent, as are a growing number of lawmakers – including a bipartisan group of 29 U.S. senators.15 Meanwhile, numerous lawmakers have introduced legislation, including the bipartisan CONNECT for Health Act, which would grant CMS standing authority to make a number of positive changes on a permanent basis.16

Here are the specific policies that we recommend Congress make permanent.

• Continue allowing patients to use telehealth outside of rural areas and at home.

• Continue allowing providers to deliver care to both established and new patients.

• Continue allowing licensed providers to practice across state lines. Because states typically require that providers must be licensed in the state where the patient is located, current law would require providers keep multiple active licenses in order to serve patients residing in other states. Though CMS has temporarily lifted these licensing rules for Medicare patients, after the Covid crisis passes federal legislation should empower providers to use their own location as the nexus in which care takes place for the purposes of payment – making treating patients across state lines more accessible.

• Continue allowing health care providers to use store-and-forward technologies where medically appropriate.

• Do not impose payment parity for telehealth services versus those provided in person. To encourage telehealth adoption and to ease the financial strain of the pandemic, Medicare is currently reimbursing health care providers for telehealth services as if provided in-person. This makes sense during a public health crisis where the goal is to encourage telehealth use, but at other time there’s little reason to peg remote rates to in-person rates. Part of the promise of telehealth is that it can reduce costs. For example, when care is provided remotely, providers don’t have to clean exam rooms, waiting rooms, and other spaces. Reimbursement should reflect these savings.

SECTION 05

Additional policies that would increase access:

We also recommend the following reforms that go beyond what Medicare has done to-date.

• States, too, should allow health care providers to practice across state lines. Medical protectionism makes no sense in a digital age. Because professional licensure is primarily a state responsibility, states should remove licensing barriers that prevent out-of-state doctors and nurses from delivering care to in-state residents. States can do this unilaterally by automatically recognizing out-of-state licenses or by entering into multistate compacts, the members of which agree to recognize each other’s licenses.

• Expand broadband access. Except for audio-only (telephone) visits, telehealth requires fast and reliable broadband internet access. Though Congress and the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) have funded such access through the Covid-19 Telehealth Program and the Rural Digital Opportunity Fund, broadband connectivity still lags in some parts of the country. Structural changes, like reducing the bureaucratic and regulatory obstacles to getting more providers involved, will help more people realize the potential of telehealth.

• Study the outcomes. The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) should use the change in health care delivery as an opportunity to analyze the effectiveness of telehealth. It is important to study the effects of recent changes on utilization, access, and costs to inform future policy making. However, Congress should not allow the appropriate desire for further study to stand in the way of quickly implementing reforms that expand patients’ access to telehealth services.

• Remove barriers to affordable care. The ultimate goal of all health reform efforts should be to ensure that everyone has access to the high-quality health care they need, when they need it, at a price they can afford. Telehealth can help with that, to be sure, but policy makers should also adopt sensible reforms that reduce costs and expand access to affordable care and coverage for everyone.

Conclusion

Widespread adoption of telehealth services during the Covid-19 pandemic has given millions of Americans their first real taste of the promise of telehealth. To be sure, there will always be a role for in-person care. And telehealth is not a panacea for the widely acknowledged failings of the U.S. health care system. But it is a very powerful tool, one that holds great promise to make life better for patients and especially for those who are elderly or infirm or who simply find in-person visits a challenge. But for that promise to become a reality, payers and policymakers must act. They must break down the regulatory and legal barriers that stand in the way of affordable, widespread access to telehealth. This is not a left-right issue. Our organizations stand together, ready to help America realize the promise of telehealth beyond the emergency.

This paper was written by Arielle Kane Director of Health Care, Progressive Policy Institute and Dean Clancy Senior Health Policy Fellow, Americans for Prosperity.

Invest in a Healthier America

The pandemic has thrown the shortcomings and inequities of America’s health care system into sharp relief. These include the extreme vulnerability of the elderly in nursing homes; the poor health status of impoverished and minority communities; regulatory obstacles to deploying telemedicine; and, a lack of basic medical equipment and surge capacity in hospitals.

There’s never been a better time to fundamentally change the way we deliver and pay for health care. Progressives should build on the foundation of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) to finish the job of universal coverage. But there’s an even bigger challenge: Driving down the exorbitant cost of medical treatment in America, which drives up insurance costs, lowers wages, and sucks up resources we need for social investments that promote public health.

It’s time for a new approach to regulated competition that caps medical prices and uses global budgets to create incentives for improving health on the front end to reduce the need for heroic interventions on the back end. These steps will generate large societal savings that we can invest in improving the “social determinants” of a healthier society – especially better housing, schools, nutrition, public safety and opportunities for our most vulnerable citizens.

The coronavirus pandemic has laid bare the weaknesses of the American health care system. Despite the fact that we spend far more on health care than any other advanced country in the world, we have worse outcomes. The United States spends 18 percent of its GDP — nearly twice as much as the average of the 11 OECD countries — yet has the lowest life expectancy and the most uninsured people. This grim reality set the stage for the novel coronavirus to rip through the population and take a particularly high toll on vulnerable populations.

The virus has disproportionately impacted the elderly, low-income people and people of color. According to the New York Times, 42 percent of the more than 130,000 U.S. coronavirus deaths are tied to nursing homes. A lack of resources, including testing and personal protective equipment, low-paid vulnerable direct care workers compounded with the defenseless elderly population they serve, was a tinderbox ignited by the virus.

In every age bracket, Black people are dying at rates equivalent to white people a decade older. There are likely a number of reasons for the variation in death rates.

For one, Black and Latinx citizens may be more likely to contract the virus because they are more likely to work in grocery stores, direct care, food processing and public transportation — jobs deemed “essential.” In addition, they are more likely to suffer from chronic conditions like hypertension, obesity, diabetes, and lung disease, and have less access to good health care services because of poverty and the legacy of racial discrimination.

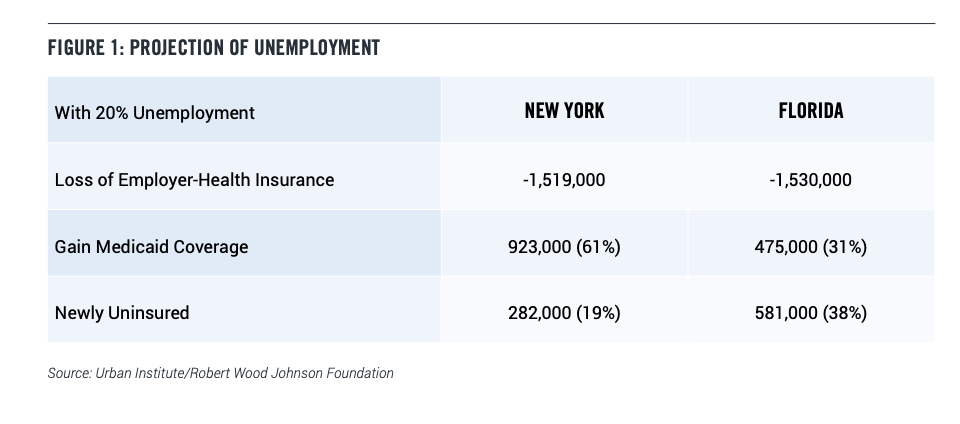

The pandemic also has illuminated a fundamental lack of resilience America’s health care system. For example, more than five million Americans have lost their health coverage because it was tied to jobs they lost in the shutdown. They should be able to turn to Medicaid for coverage, but 13 states have refused to expand their Medicaid programs under the ACA. Thus the rise of uninsured is expected to hit these Republic-led states harder.

Covid-19, and the subsequent shelter in place orders, have exacerbated mental health conditions. Because many people couldn’t access their usual care, drug overdoses have increased during the pandemic. Treating patients via telehealth might not work for every condition, but it is effective for many mental health issues. Seeing this, many states have changed regulations to expand access to telehealth services.

Even as we fight to contain the Covid-19 pandemic today, U.S. policymakers should be looking ahead to constructing a more innovative health care system that covers everyone, holds medical costs down, creates healthier conditions in low-income communities and makes our society more resilient against future public health emergencies.

PPI has proposed a comprehensive architecture for health care reform. This report highlights two critically important steps forward: Plugging coverage gaps and adopting global budgeting to lower health care costs.

First, to make coverage truly universal, lawmakers should expand the Affordable Care Act’s subsidies, set up auto-enrollment mechanisms for the uninsured, and cap the price of medical services. The recent vote to approve Medicaid expansion in Oklahoma demonstrates that Republican resistance to expanding Medicaid as allowed by the ACA is slowly melting away.

In addition, PPI has endorsed a “Midlife Medicare” buy-in. As conceived by health care analyst and historian Paul Starr, Midlife Medicare would respect the traditional status of Medicare as a program for the elderly by allowing the not-quite retired (those aged 55-65) an opportunity to buy their benefits early. By taking many older, high-cost people out of the individual insurance market, Midlife Medicare would lower premiums for younger workers.

Second, we need to change the perverse incentives in our system for overspending on after-the-fact medical treatment so that we can invest more in upstream social determinants of health.

Getting everyone covered is essential, but it will not by itself address racial disparities in health. Health status is a product of more than medical care – things like public safety, housing, education, transportation, and nutrition all impact a person’s health. The United States spends roughly 18 percent of GDP on health care – the most of any OECD country. At the same time, America spends the least on social services.

Reducing U.S. health care spending to 12 percent of GDP – the amount that the second highest cost country, Switzerland, spends on health care – would free up roughly $1 trillion dollars to invest in a broad array of social services that are conducive to better health. For example, the data overwhelming demonstrate that access to affordable, quality, safe housing improves health outcomes.

As former Oregon Governor John Kitzhaber, MD argues, America needs to shift from an after-the-fact medical treatment model to a sickness-prevention and health promotion model. The only to break the back of health care cost inflation, he argues, is to embrace global budgeting:

“Doing so requires that everyone has timely access to effective, affordable, quality medical care; and that we have room in the budget to make strategic long-term investments in stable families, housing, nutrition, safe communities and economic opportunity. In other words, the key elements are universal coverage, financial sustainability and effective social investment. The economic reality is that the only way these three elements can exist together, is if universal coverage is accompanied by a reduction in the rate of medical inflation; and the only way we can effectively reduce medical inflation is through a global budget indexed to a sustainable growth rate.”

The key mechanism to reduce the cost of medical services is global budgeting. A global budget is a fixed amount of money all payers in a region agree to pay to deliver care to a defined population.

For example, hospitals in Maryland, which operate under a global budget, found themselves better positioned to weather the Covid storm because their revenues did not drastically change when elective procedures stopped and they continued receiving predictable revenue as they delivered care to Covid patients. Rural hospitals in Pennsylvania also recently moved to this model.

Global budgets also eliminate incentives for hospitals to inflate prices for Covid-19-related services to compensate for the loss of normal revenue. A recent analysis in JAMA outlines why these hospitals will be better positioned to bounce back from Covid-related economic hardship.

The federal government should take its cue from Maryland and Pennsylvania. Rather than set a federal cap on health care spending, Washington should encourage each state to set its own global budget and work with the payers and providers in its borders to work out the details.

Washington also should give States should also have greater flexibility to spend Medicaid dollars on housing and other social determinants that can reduce health care expenditures, as Oregon has done.

There is no question that dramatic reform of the health care system will be difficult. But the U.S. has long been the outlier of advanced countries – overpaying for poor health outcomes. We have a crisis that has laid bare the weaknesses of our system and policymakers should not let the moment pass without dramatically reforming our system more cost effective, productive and resilient for the future.

Americans are Worried about Health Care Prices — What Can Congress Do?

The Trump administration’s hospital price transparency rule, upheld by a district court judge this week, will require hospitals to post publicly the rates they negotiate with insurers beginning in January.

President Trump called it a “BIG VICTORY for patients — Federal court UPHOLDS hospital price transparency. Patients deserve to know the price of care BEFORE they enter the hospital. Because of my action, they will. This may very well be bigger than healthcare itself.”

This is undoubtedly false. Price transparency is always a good thing, in health care or any other market. But the effect of Trump’s order is likely to be modest at best.

The idea is that if prices are posted, informed consumers — aka patients — can compare prices between providers for elective surgeries and procedures. This would encourage them to pick lower cost providers and subsequently, providers would lower their prices to remain competitive.

But the jury is still out on how much affect price transparency could have on overall health care costs. One study found that only 2 percent of patients with health plans that offered price transparency tools used them. There are three main reasons that patients are not responsive to price in health care:

1. People with insurance are insulated from health care costs at the point of purchase

2. Patients follow their doctors’ referrals rather than shopping for care on their own

3. Patients see price as a proxy for quality and associate higher prices with higher quality care

Even though they don’t price shop, Americans are still concerned about health care costs. Before the pandemic, 1 in 3 Americans were worried about being able to afford health care. Though price transparency isn’t likely to change consumer behavior, it could help insurers negotiate better prices with hospitals. It remains to be seen. But in the meantime, hospitals are appealing the court’s decision.

To support efforts to reduce health care prices, Congress could:

Require hospitals to post prices publicly. Codifying the rule would render the lawsuit challenging the Trump rule moot.

Empower the FTC. Giving the Federal Trade Commission more resources to review and limit hospital mergers could reduce health care prices. Hospital mergers are continuing despite the pandemic and cash-poor physician practices are selling out to larger hospital chains. The data show that consolidated markets have higher health care prices. Giving the FTC more resources to consider the market implications of these mergers and acquisitions could limit market consolidation and price increases.

Ban surprise bills. Congress could resume negotiations over a comprehensive package to ban surprise medical bills. My preferred approach is a benchmark price for out-of-network services tied to Medicare prices. Tying the benchmark to in-network prices or median charges has perverse incentives to increase in-network prices. Is it politically difficult? Yes. But it’s necessary to both protect patients and to stop the exponential growth of health care costs in the U.S.

Read more here.

COVID-19 is unraveling the issue of surprise billing in America

Back in December, Congress failed to reach an agreement on “surprise billing” legislation. A surprise bill is when patients get an out-of-network bill from a provider at an in-network facility.

Lawmakers couldn’t decide if an arbitration model — where billing disagreements would be sent to a third-party review board — or if a benchmark model — where payments would be based on a set benchmark price — was best.

Now in the era of Covid, this failure is coming home to roost.

Federal law requires private health plans to cover all Covid-19 testing. But because there is no set benchmark price labs can charge whatever they want as long as they list it publicly. Most labs charge around $100 for a Covid-19 test, some unscrupulous labs are charging as much $2,315 for the same test.

Patients, of course, will ultimately bear the cost through higher premiums. Furthermore, the failure to ban surprise bills means that out-of-network labs can balance bill the patient on top of the fee they charge their health plan. Balance billing is when an out-of-network lab or hospital first bills insurance but because there is no agreed upon price, then balance bills any remaining balance the insurer refuses to pay back to the patient.

Labs aren’t the only ones inflating costs to exploit the Covid-19 emergency. Some hospitals are billing patients hundreds of thousands of dollars for treating the disease, even though hospitals that take federal bailout dollars are supposed to be barred from balance billing patients. This is because even if the hospital takes federal funding, if the doctors that work there are out-of-network, they (or their staffing companies) can send surprise bills to patients.

But there are some policy levers that could help:

Bar billing above what Medicare pays. Medicare initially was paying $50 per Covid test. But because supply was lagging, it upped its reimbursement to $100 to encourage more testing. It seems to have worked — supply for Covid tests is roughly aligned with demand. Congress should limit all labs that take Medicare payments from billing private insurers above the rates set by Medicare.

Ban surprise Medical bills. Congress could resume negotiations over a comprehensive package to ban surprise medical bills. My preferred approach is a benchmark price for out-of-network services tied to Medicare prices. Tying the benchmark to in-network prices or median charges has perverse incentives to increase in-network prices. Is it politically difficult? Yes. But it’s necessary to both protect patients and to stop the exponential growth of health care costs in the U.S.

Consider a global budget. Hospitals do have a revenue problem. That’s mainly because many stopped doing lucrative “elective” procedures to concentrate on handling the surge of Covid-19 patients. But hospitals that have a “global” budget are better positioned to weather the Covid storm. A global budget is a fixed amount of money all payers in a region agree to pay hospitals to deliver care to a defined population. All Maryland hospitals, for example, and more recently rural hospitals in Pennsylvania, use global budgets to pay for medical care. This model eliminates incentives for hospitals to jack up prices for Covid-19 services to compensate for the loss of normal revenue. A recent analysis in JAMA outlines why these hospitals will be better positioned to bounce back from Covid-related economic hardship. While moving to a global budget will be difficult, it makes more sense now than ever and policymakers should not let the moment pass.

Read more here.

We can contain the spread of COVID-19 — but the federal government must step up before it’s too late

States and localities are proceeding with “opening” their economies despite the fact that most states have not met the re-opening criteria put forward by the White House.

In order to head off spikes in cases, states and localities will need aggressive testing, contact tracing, and isolation programs. Testing is only as good as what you do with that information. And the key next steps are to inform the person with the positive or negative test and then track the contacts of all positive tests — and asking those people to self-quarantine — ideally giving people a place to do so if they don’t have one of their own. Because the U.S. has such widespread cases of COVID-19, federal support of contact tracing programs is needed.

The best way for the federal government to contain the spread of the coronavirus is to provide guidance and funding to state and local programs which then do the work on the ground:

1. Numbers. Experts estimate the U.S. will need 100,000 to 300,000 contact tracers. These can be epidemiologists, nurses, and trained citizens. Ideally, these people will be employed by local health departments in their area. The National Association of County and City Health Officials says public health departments should have 30 contact tracers per 100,000 people.

2. Funding. Andy Slavitt, former director of Medicare and Medicaid in the Obama administration, and Scott Gottlieb, former director of the Food and Drug Administration for President Trump, called for $46 billion in federal funding for contact tracing and related activities to bolster public health departments and contain the spread of the virus.

3. Support local public health departments. Rather than creating a new federal entity — which would take time and additional bureaucracy — it makes the most sense to quickly funnel funding to local health departments on the ground. To inform policymakers, data should be standardized and centralized at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

4. Provide cultural competency guidance. Much of the success of contact tracing relies on the contact tracer getting the interviewee to divulge who they have been in contact with. This requires the ability to create trust with people quickly over the phone — at a time when many people don’t answer calls from unknown numbers. Cultural competency is an integral part of an interviewer’s ability to quickly build rapport. It is vital that the federal government provide local jurisdictions guidance on cultural competency including local jurisdictions hire contact tracers from a variety of backgrounds and from communities that are most affected.

5. Training. The federal government should support the training of contact tracers by providing funding and guidance. The hope is that these jobs will be short-lived as once the spread is under control, the surge of contact tracers will no longer be necessary. Thus the federal government should also support transitioning contact tracers into other positions that support the health of communities.

6. Privacy. As large technology companies work to develop products that support contact tracing efforts, it is paramount that they work with public health departments. They should not solely control the data collected. Furthermore, the efforts to develop new products should be in conjunction with public health departments not siloed apart from them.

Read more here.

Community Health Centers and COVID-19

Community Health Centers (CHCs) have an important role to play in SARS-CoV-2 response. CHCs are community-based and organizations that provide primary care, mental health care and even dental care to populations with limited access to health care. Both House and Senate members are pushing leadership (Senate, House) to include increased funding for CHCs in the next relief package.

Funding is an important first step to helping CHCs provide care to the 28 million low-income and disproportionately uninsured patients they see annually. But it’s not the only issue at play.

Any legislative action to support community health centers should:

1. Authorize relief funding

2. Expand telehealth services

3. Increase the number of Community Health Workers

Authorize relief funding: Like most health care providers, CHCs saw a dramatic decline in appointments during the second quarter of this year — almost 40 percent. As a result, nearly 2,000 sites closed their doors. Though the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act directed $1.32 billion to Community Health Centers for COVID-19 response and to maintain some regular capacity, it was not enough. To provide long-term stability for CHCs, the call for a five-year extension with $69.7 billion in funding makes sense.

Expand telehealth services: Many hospitals and physicians offices were able to adapt to the pandemic and move appointments online. Unfortunately, unlike their more resourced counterparts, CHCs were not prepared to transition appointments to telehealth. In 2018, 56 percent of CHCs did not have any telehealth use. Barriers included limited reimbursement, equipment, training for providers and inadequate broadband. CHCs provide mental health services, chronic care management, and primary. Moving these services online would help them better serve patients and meet them where they are at. Relief funding should include dedicated dollars to help CHCs modernize for the 21st century.

Increase the number of Community Health Workers: CHCs provide primary care services, mental health services, oral health services and countless other procedures to underserved populations on a sliding fee schedule. But often people don’t know the services are there and available to them. I find the health care system difficult to navigate as someone who has a career in health policy — I don’t know how to find out if a dentist is good in a new city or how to establish a relationship with a new primary care doctor. Yet there are millions of Americans who are uninsured, maybe who don’t speak English, and then they are expected to navigate a bureaucratic, convoluted system on their own.

Community Health Workers (CHWs) are worth their weight in gold — or more precisely they save $2.47 for every dollar spent. CHWs typically serve their own communities and are hired to provide social support, help patients navigate the health system and connect people to any services they may need. As we attempt to mitigate the damage of COVID-19 and move beyond this crisis, CHWs can be a key part to helping communities rebuild and access needed health care services — in particular services offered at Community Health Centers. One can imagine that it would make sense to have CHWs work in communities with meat packing facilities, nursing homes, and other communities ravaged by COVID-19. Unlike contact tracers which are necessary to get us through the pandemic, with adequate investment, CHW jobs could stick around for a while to provide vital services to underserved communities.

COVID-19 fact of the week: People with type A blood are 50 percent more likely to require a ventilator, according to a new study of patients in Italy and Spain. Furthermore, 23andme found that people with O type blood are less susceptible to the virus.

Read more here.

America’s COVID-19 Debacle: A Chronology

Updated on October 21, 2020.

As the coronavirus pandemic enters its 10th month, the United States continues to lead the world in deaths and infection rates. The hard truth is America ranks dead last when it comes to responding effectively to COVID-19.

As of mid-October, more than 222,000 Americans have been killed by the virus, some 70,000 more fatalities than second-ranking Brazil. The United States accounts for about one-fifth of global deaths. We have more than 8.2 million confirmed cases of COVID-19, and the number is rising as the pandemic’s “third wave” spreads throughout the Midwest and mountain West, and in rural America.

Since the United States is rich and technologically advanced, and spends far more than other countries on health care, there can only be one explanation for our abysmal showing against the coronavirus pandemic: An epic failure of political leadership, especially at the top.

The Trump administration’s manifest inability to contain the pandemic has cost tens of thousands of preventable U.S. deaths and prolonged the nation’s worst economic crisis since the Great Depression. More than 50 million Americans have filed for unemployment, countless small businesses have gone under, and national output has plummeted.

COVID-19 deaths have been concentrated among the elderly in nursing homes; front-line health workers and those in “essential” industries like meat packing; and, poor and minority communities where people are more likely to make medical conditions that make them more vulnerable to the virus.

The crisis also has aggravated the nation’s pre-existing economic inequities. Layoffs have been heaviest in low-paid hospitality and service jobs, while many office workers with college degrees have been able to keep working remotely. Even as the economy has contracted, the stock market keeps rising, widening the nation’s wealth gap.

Millions of K-12 students suffered acute learning losses when public schools closed last spring, and many disadvantaged children also lost access to school meals. Many schools remain closed this fall, putting a heavy burden on parents forced to stay home to look after their kids and help them keep up with their studies online.

No one expected the United States to escape the ravages of COVID-19 unscathed. But the enormous scale of our human and economic losses was not inevitable. Other countries have managed the COVID-19 crisis far more effectively. For example, South Korea, which reported its first case of infection on the same day as the United States, reports less than 400 deaths and about 22,000 cases.

In fact, the COVID-19 crisis has posed a kind of “governance stress test” to countries around the world. It is casting a remorseless light on the quality of each country’s political leadership and the competence of its national government.

Comparing America’s performance with that of other countries, the political scientist Francis Fukuyama concludes that President Donald Trump proved incapable of rising to the challenge:

“It was the country’s singular misfortune to have the most incompetent and divisive leader in its modern history at the helm when the crisis hit, and his mode of governance did not change under pressure. Having spent his term at war with the state he heads, he was unable to deploy it effectively when the situation demanded. Having judged that his political fortunes were best served by confrontation and rancor than national unity, he has used the crisis to pick fights and increase social cleavages. American underperformance during the pandemic has several causes, but the most significant has been a national leader who has failed to lead.”

Now, with an eye to this November’s election, President Trump and his party seek to convince Americans the debacle they have been witnessing throughout 2020 is a mirage. In a surreal spectacle, speaker after speaker in the Republican National Convention extolled Trump’s “decisive action” against COVID-19, while Trump himself bragged about ordering an “unprecedented national mobilization” against the “China virus.”

In fact, the mobilization of national will and resources our country needed never happened. The president’s negligence and disdain for taking elementary precautions against the disease, like wearing a mask, has contributed to outbreaks in the White House itself, infecting him and his family and many top staffers.

Even now, with the rate of infection surging again, it’s painfully clear that President Trump has no plan to contain the disease. Instead he’s fighting it with happy talk and promises that a vaccine is just around the corner. He and his party have given higher priority to adding another conservative Supreme Court justice than to passing a major COVID-19 relief bill to check the disease, boost our sputtering economy and maintain unemployment benefits.

The Progressive Policy Institute believes the 2020 presidential election should be a referendum on Donald Trump’s handling of the gravest national crisis he has faced as president. To help voters distinguish fact from fiction, PPI has assembled this comprehensive chronology of key events and milestones in the COVID-19 crisis. As it continues to unfold, we will update this instant historical record as necessary. If readers think we have missed any important events or information, please notify Kate Hinsche at khinsche@ppionline.org.

*Note: The main source for each entry can be found by clicking on the date.

COVID-19: Chronology of a Debacle

2017

JANUARY 12 – Speaking at Georgetown University, Dr. Anthony Fauci, Director of the National Institute on Allergy and Infectious Diseases, urges the incoming Trump administration to be prepared for outbreaks of viral diseases. “If there’s one message that I want to leave with you today based on my experience, it is that there is no question that there will be a challenge to the coming administration in the arena of infectious diseases.”

JANUARY 13 – Outgoing Obama administration officials run a crisis simulation for President-elect Trump’s national security team on how to react to the outbreak of a deadly respiratory disease. The incoming administration is also given a 69-page playbook with best practices for handling global pandemics.

MAY 11 – Dan Coats, Director of National Intelligence, reports to Congress about threats to the United States, including global pandemics.

MAY 27 – In his first budget, President Trump proposes a $1.3 billion cut in the Center for Disease Control (CDC) for 2018. In each year of his presidency, President Trump has proposed similar cuts to the CDC’s funding. (2019) (2020) (2021)

2018

FEBRUARY 13 – DNI Coats again warns Congress about the threat of a global pandemic.

APRIL 10 – Tom Bossert, White House homeland security advisor, resigns at the request of National Security Advisor John Bolton. Bossert had repeatedly called for a comprehensive biodefense strategy against pandemics and biological attacks.

MAY 7 – Speaking at Emory University to mark the 100th anniversary of the 1918 influenza pandemic, Luciana Borio, the National Security Council’s Director of Medical and Biodefense preparedness, warns “The threat of pandemic flu is the number one health security concern. Are we ready to respond? I fear the answer is no.”

MAY 8 – President Trump calls for cuts in emergency funds for Ebola and other pandemics, as well as the State Department’s Complex Crisis Fund for “emerging or unforeseen crises.”

MAY 10 – As part of his effort to “streamline” the National Security Council, Bolton disbands the Directorate for Global Health Security and Biodefense and removes its director, Rear Admiral Timothy Ziemer.

OCTOBER 19 – “In a move that worries public health experts,” the New York Times reports, “the federal government is quietly shutting down a surveillance program for dangerous animal viruses that someday may infect humans.”

2019

JANUARY 29 – DNI Coats again warns Congress that the United States remains “vulnerable to the next flu pandemic or large scale outbreak of a contagious disease that could lead to massive rates of death and disability, severely affect the world economy, strain international resources, and increase calls on the United States for support.”

JULY 28 – DNI Coats, who had publicly differed with President Trump over Russia’s interference in the 2016 election, steps down.

SEPTEMBER 15 – The President’s Council of Economic Advisers (CEA) warns that an influenza pandemic could cause enormous health and economic losses.

OCTOBER 1 – The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) issues a draft report on a series of exercises code-named “Crimson Contagion.” The report warns that the federal government is “underfunded, underprepared and uncoordinated” to fight an influenza pandemic.

DECEMBER 31 – China reports the outbreak of the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) to the World Health Organization.

2020

JANUARY

JANUARY 6 – The CDC issues a travel notice for Wuhan, China following reports of the outbreak of a new infectious disease.

JANUARY 10 – Chinese state media reports first death in China due to the novel coronavirus.

JANUARY 18 – HHS Secretary Alex Azar warns President Trump of the possibility of a pandemic stemming from the outbreak in China.

JANUARY 21 – The CDC reports the first coronavirus case in the United States: An unidentified Washington State man, in his early 30s who recently had traveled to Wuhan.

JANUARY 22 – In an interview in Davos, Switzerland, President Trump dismisses concerns about the coronavirus, saying “We have it totally under control.”

JANUARY 22 – White House officials turn down an offer to buy millions of N95 masks manufactured in America, according to the manufacturer.

JANUARY 24 – President Trump congratulates Chinese President Xi on his handling of the outbreak in Wuhan, tweeting: “The United States greatly appreciates their efforts and transparency.”

JANUARY 29 – White House advisor Peter Navarro circulates a memo outlining the risks of coronavirus contagion. It estimates that, in a worst-case scenario, a pandemic could claim up to 500,000 U.S. lives and cost close to $6 trillion.

JANUARY 30 – Amid serious outbreaks in Italy and China, the World Health Organization (WHO) declares COVID-19 a global public health emergency.

JANUARY 30 – HHS Secretary Azar again warns President Trump of the possibility of a pandemic. The New York Times reports, “Mr. Azar was blunt, warning that the virus could develop into a pandemic and arguing that China should be criticized for failing to be transparent.”

JANUARY 30 – In a press conference, President Trump assures Americans have little to worry about: “We think we have it very well under control. We have very little problem in this country at this moment — five — and those people are all recuperating successfully.”

JANUARY 31 – President Trump issues an executive order ostensibly banning travel to and from China.

FEBRUARY

FEBRUARY 2 – “We pretty much shut it (coronavirus) down coming in from China,” President Trump tells Fox News’s, Sean Hannity.

FEBRUARY 6 – COVID-19 claims its first U.S. victim: Patricia Dowd, 57, of Santa Clara, California. This fact isn’t disclosed until after an April 21 autopsy.

FEBRUARY 8 – Labs receiving coronavirus tests from the CDC start to complain that they don’t work properly. The problem isn’t resolved until weeks later when the FDA waives rules against tests developed elsewhere.

FEBRUARY 10 – President Trump continues to express confidence in China’s management of the pandemic. He tells governors at the White House that President Xi of China feels “very confident” because “by April or during the month of April, the heat, generally speaking, kills this kind of virus.”

FEBRUARY 23 – Navarro sends a second memo to President Trump, warning of the “increasing probability of a full-blown COVID-19 pandemic that could infect as many as 100 million Americans, with a loss of life of as many as 1-2 million souls.”

FEBRUARY 24 – “The Coronavirus is very much under control in the USA,” President Trump tweets.

FEBRUARY 26 – President Trump introduces the White House coronavirus task force, even while continuing to minimize the danger: “The flu, in our country, kills from 25,000 people to 69,000 people a year… And again, when you have 15 [COVID-19 victims], and the 15 within a couple of days is going to be down to close to zero, that’s a pretty good job we’ve done.”

FEBRUARY 27 – “It’s going to disappear. One day it’s like a miracle, it will disappear,” President Trump declares in a White House briefing with African American leaders.

FEBRUARY 29 – Stung by criticism of White House inaction, President Trump tells the press: “We’ve taken the most aggressive actions to confront the coronavirus. They are the most aggressive taken by any country and we’re the number one travel destination anywhere in the world, yet we have far fewer cases of the disease than even countries with much less travel or a much smaller population.”

MARCH

MARCH 1 – First reported U.S. COVID-19 death in Washington State. The unidentified patient was a man in his 50s with serious health problems.

MARCH 2 – President Trump predicts that a COVID-19 vaccine is imminent. “I’ve heard very quick numbers, that of months.” This contradicts Dr. Fauci’s repeated warnings that a vaccine may not be available for a year or a year and a half.

MARCH 6 – At a press briefing, President Trump boasts about his understanding of the coronavirus: “I like this stuff. I really get it. People are surprised that I understand it. […] Every one of these doctors said, ‘How do you know so much about this?’ Maybe I have a natural ability.”

MARCH 6 – “Anybody that wants a test can get a test,” President Trump asserts after touring the CDC headquarters in Atlanta.

MARCH 6 – The Coronavirus Preparedness and Response Supplemental Appropriations Act — Congress’s first response to the pandemic — becomes law. It provides $8.3 billion in emergency funding for federal agencies to combat coronavirus.

MARCH 9 – In a tweet, President Trump again compares COVID-19 to the flu: “So last year 37,000 Americans died from the common Flu. It averages between 27,000 and 70,000 per year. Nothing is shut down, life & the economy go on. At this moment there are 546 confirmed cases of CoronaVirus, with 22 deaths. Think about that!”

MARCH 10 – Following a meeting with Republican Senators, President Trump again praises his administration’s handling of COVID-19: “It hit the world. And we’re prepared, and we’re doing a great job with it.”

MARCH 10 – In a televised address to the nation, President Trump asserts, inaccurately, that Americans won’t have to pay for COVID-19 treatment.

MARCH 11 – In a press briefing, President Trump again downplays the danger of COVID-19. “The vast majority of Americans, the risk is very, very low. Young and healthy people can expect to recover fully and quickly if they should get the virus.”

MARCH 11 – President Trump announces increased travel restrictions for 26 European countries. In practice, however, the order is riddled with loopholes that create long lines for some and zero screening for others.

MARCH 11 – WHO upgrades COVID-19 from a public health emergency to a global pandemic.

MARCH 11– News reports say that the United States has tested just over 7,000 people for the coronavirus, compared to 222,395 tests conducted in South Korea. Both countries reported their first COVID-19 case on the same day.

MARCH 13 – Asked by a reporter if he would “take responsibility for the failure to disseminate larger quantities of tests earlier,” President Trump replies, “I don’t take responsibility at all.”

MARCH 15 – 33 states plus the District of Columbia close their public schools.

MARCH 16 – President Trump announces self-isolation guidelines for Americans to follow for the next 15 days.

MARCH 16 – President Trump denies understating the danger of COVID-19: “I’ve always known this is a real — this is a pandemic. I felt it was a pandemic long before it was called a pandemic.”

MARCH 17 – U.S. COVID-19 death toll exceeds 100.

MARCH 18 – Congress passes a second relief bill, the Families First Coronavirus Response Act. It provides close to $3.5 billion for coronavirus testing, 14-day paid leave for workers affected by the pandemic, and removes work requirements for food stamps.

MARCH 19 – President Trump touts, without evidence, chloroquine, and hydroxychloroquine as a potential cure to COVID-19.

MARCH 22 – In a flurry of tweets, President Trump voices frustration over governors’ handling of the pandemic. The public, however, expresses far more confidence in their governors than the president in national polls.

MARCH 23 – The first nine states implement stay-at-home orders (Washington, Oregon, California, Louisiana, Illinois, Ohio, New York, Massachusetts, and New Jersey).

MARCH 23 – The media reports that 48 states plus the District of Columbia have closed their public schools for the rest of the academic year.

MARCH 24 – In the daily coronavirus task force briefing, President Trump imagines the U.S. economy reopening in a matter of weeks: “I would love to have the country opened up and just raring to go by Easter… I think Easter Sunday — you’ll have packed churches all over our country.”

MARCH 25 – In the daily briefing, President Trump claims the United States leads the world in testing. “We have tested, by far, more than anybody…There’s nobody even close. And our tests are the best tests.” On a per-capita basis, however, the United States ranks low on tests.

MARCH 25 – U.S. COVID-19 death toll passes 1,000.

MARCH 26 – Twelve more states implement stay-at-home orders (Idaho, Colorado, New Mexico, Michigan, Wisconsin, Kentucky, Indiana, West Virginia, Hawaii, Connecticut, Vermont, and Delaware).

MARCH 26 – U.S. cases surge to 82,404, overtaking both Italy and China to make America the world’s leader in reported COVID-19 infections.

MARCH 27 – Congress passes its third and largest aid bill, the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act. The CARES Act provides $2 trillion to aid businesses and workers, procure medical supplies and equipment, and expand Unemployment Insurance.

MARCH 28 – In signing the CARES Act, President Trump claims that the Inspector General charged with oversight of the bill requires his permission before reporting to Congress.

MARCH 30 – Nine more states implement stay-at-home orders.

MARCH 31 – President Trump concedes that COVID-19 “is not the flu. It’s vicious. When you send a friend to the hospital… And you call up the next day, ‘how’s he doing?’ And he’s in a coma? This is not the flu.”

MARCH 31 – U.S. COVID-19 death toll surpasses 5,000.

APRIL

APRIL 3 – President Trump tells the public that COVID-19 is retreating. “I said it was going away – and it is going away.”

APRIL 3 – New York City COVID-19 deaths surpass the number of Americans killed on 9/11.

APRIL 3 – The U.S. Chamber of Commerce reports that 24% of small businesses have closed due to the coronavirus lockdown and predicts another 40% could close soon.

APRIL 3 – In response to the CDC’s recommendation that Americans wear facial masks, President Trump declines to lead by example, saying, “I don’t think I’m going to be doing it.”

APRIL 4 – U.S. COVID-19 death toll passes 10,000.

APRIL 6 – Twelve more states issue stay-at-home orders, bringing the total number to 42.

APRIL 6 – The United States overtakes Spain’s COVID-19 death toll with 13,298 fatalities, the second-highest in the world behind Italy.

APRIL 7 – President Trump ousts Glenn Fine, the DOD Inspector General picked to oversee the implementation of the CARES Act.

APRIL 9 – The United States overtakes Italy’s COVID-19 death toll with 19,802 fatalities, becoming the world leader in COVID-19 mortality.

APRIL 14 – President Trump halts America’s contribution to WHO funding and calls for an investigation into the agency’s role in ”severely mismanaging and covering up the spread of the coronavirus.”

APRIL 14 – U.S. COVID-19 death toll passes 30,000.

APRIL 17 – In a series of tweets, President Trump encourages protests against Democratic governors’ social distancing restrictions: “LIBERATE MICHIGAN,” “LIBERATE MINNESOTA,” “LIBERATE VIRGINIA.

APRIL 17 – The BLS reports that national unemployment grew 0.9% in March, to 7.4 million unemployed or 4.4%.

APRIL 19 – U.S. COVID-19 death toll passes 40,000.

APRIL 21 – Tests from autopsies performed in early February come back positive for coronavirus, revealing COVID-19 deaths before the CDC reported the first U.S. fatality on March 1.

APRIL 21 – The White House removes Rick Bright, Director of the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA). Bright had said the president’s claims for the curative powers of chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine “clearly lack scientific merit.”

APRIL 23 – In a fourth relief bill, Congress approves $484 billion in additional funding for small businesses, hospitals, and coronavirus testing.

APRIL 23 – President Trump is widely ridiculed for musing in a task force briefing that COVID-19 might be treatable with disinfectants and sunlight. “I see the disinfectant, where it knocks [the virus] out in a minute… is there a way we can do something like that, by injection inside or almost a cleaning?”

APRIL 24 – Georgia becomes the first state to start lifting restrictions and reopening some businesses.

APRIL 28 – U.S. COVID-19 death toll surpasses the official tally (58,300) of Americans who died in the 1955-1975 Vietnam War.

APRIL 29 – The Bureau of Economic Analysis reports that the U.S. economy shrank at an annual rate of 4.8% in the first quarter of 2020.

MAY

MAY 1 – President Trump announces his intention to replace Christi Grimm, the Inspector General of HHS, who released a late April report documenting shortages of medical supplies and testing delays.

MAY 4 – Media reports say that almost 20 states have begun to lift social distancing restrictions.

MAY 5 – Trump announces he’ll wind down the coronavirus task force by the end of May so that the White House can focus on restarting the economy.

MAY 5 – U.S. COVID-19 death toll passes 70,000.

MAY 6 – President Trump again expresses impatience about opening the economy. “We can’t have our whole country out. We can’t do it. The country won’t take it. It won’t stand it. It’s not sustainable.”

MAY 10 – Two White House employees test positive for COVID-19.

MAY 11 – The BLS reports that the unemployment rate in April has ballooned to 14.7% with 20.5 million unemployed, much higher than at the peak of the 2008 Great Recession.

MAY 11 – President Trump castigates Pennsylvania Gov. Tom Wolf for “moving slowly” to reopen his state as protestors rally.

MAY 18 – President Trump admits he has been taking daily doses of hydroxychloroquine, which has yet to be proven effective and may even be harmful to those who contract coronavirus.

MAY 21 – President Trump, after conducting a Michigan factory tour without a face mask, explains, “I wore one in this back area, but I didn’t want to give the press the pleasure of seeing it.”

MAY 26 – U.S. COVID-19 death toll passes 100,000.

MAY 26 – 36 states have reopened or are in the process of reopening.

MAY 28 – The total number of new jobless claims surpasses 40 million.

JUNE

JUNE 2 – Trump suggests GOP move convention to Jacksonville, FL after N.C. Gov. Roy Cooper refuses to allow packed arenas.

JUNE 3 – According to a new study from the University of Minnesota, the malaria drug hydroxychloroquine does not prevent people from contracting COVID-19.

JUNE 6 – 35.4 million Americans are receiving unemployment benefits.

JUNE 8 – Following an easing of lockdown conditions in many parts of the country, infections are rising in 21 states.

JUNE 11 – U.S. COVID-19 cases surpass two million.

JUNE 11 – News outlets report that more than 20 European countries have reopened their schools. Most U.S. schools remain closed.

JUNE 16 – In an op-ed, Vice President Mike Pence dismisses reports about a “second wave” of coronavirus infections and boasts that the Trump administration is “winning the fight against the invisible enemy.”

JUNE 17 – Vice President Pence tells governors that an apparent rise in U.S. coronavirus outbreaks stems from an increase in testing.

JUNE 19 – Gov. Andrew Cuomo wraps up 111 consecutive days of widely praised coronavirus briefings as COVID-19 hospitalizations in New York have dropped below 1,000 for the first time since March 18.

JUNE 19 – Nine Texas mayors write a letter to the states’ residents, urging them to wear masks. Coronavirus cases in Texas continue to surge and the number of hospitalizations has been climbing since May.

JUNE 20 – Disregarding warnings from administration health officials against large public gatherings, Pres. Trump resumes mass campaign rallies in Tulsa, with 6,200 people in attendance.

JUNE 21 – President Trump complains that more COVID-19 testing is increasing the number of confirmed U.S. cases. “When you do testing to that extent, you’re going to find more people, you’re going to find more cases, So I said to my people, ‘Slow the testing down, please’,” he says at the Tulsa rally.

JUNE 22 – Two members of President Trump’s campaign advance team, who attended Trump’s rally in Oklahoma, test positive for coronavirus.

JUNE 22 – New data confirms that COVID-19 cases are growing in 29 states.

JUNE 23 – President Trump again insists that more tests are to blame for the increase in coronavirus infections.

JUNE 23 – At a Congressional hearing, Dr. Fauci says U.S. health officials see a “disturbing surge” of infections in some parts of the country, as Americans ignore social distancing guidelines.

JUNE 23 – Texas tallies more than 5,000 new cases in a single day for the first time. “The coronavirus is serious. It’s spreading,” Texas Gov. Greg Abbott told a local television station.

JUNE 23 – President Trump addresses a crowd of student supporters at a tightly packed megachurch in Phoenix. Trump appeared without a mask, flouting a Phoenix rule that came into force less than 72 hours earlier.

JUNE 26 – VP Pence’s Coronavirus task force hails states for “safely and responsibly” reopening their economies. Yet Texas and Florida officials reimpose restrictions on bars and restaurants amid record levels of new cases and tightening hospital capacity.

JUNE 30 – The E.U. bloc will allow visitors from 15 countries, but the U.S., Brazil and Russia were among the notable absences from the safe list.

JUNE 30 – New York Times data confirms 40,041 U.S. COVID-19 cases.

JULY

JULY 2 – Daily number of new COVID-19 cases in the U.S. tops 50,000 for the first time, the largest single-day total since the start of the pandemic.

JULY 2 – The unemployment rate declines by 2.2 percentage points to 11.1 percent, and the number of unemployed persons falls by 3.2 million to 17.8 million.

JULY 2 – GOP 2012 presidential candidate Herman Cain is hospitalized with COVID-19 a week after attending the Trump rally in Tulsa, where many attendees were not wearing masks.

JULY 5 – President Trump dismisses the impact of COVID-19 and says that while the testing of tens of millions of Americans had identified many cases, “99 percent” of them were “totally harmless.”

JULY 7 – Pres. Trump insists U.S. colleges and universities should remain open for the fall semester, citing several European school openings, “We’re very much going to put pressure on governors and everybody else to open the schools, to get them open.”

JULY 8 – The U.S. reports more than three million coronavirus cases, with all but a handful of states struggling to control outbreaks of COVID-19.

JULY 10 – The United States reports 68,000 new cases, setting a single-day record for the seventh time in 11 days.

JULY 10 – Hong Kong shuts down its school systems, reporting more than 1,400 cases and seven deaths.

JULY 11 – Disney World reopens its gates in Orlando, Florida.

JULY 11 – President Trump appears with a face mask for the first time in public, five months after administration officials recommended that all Americans wear face masks in public.

JULY 12 – Florida reports a record 15,300 new coronavirus cases, by far the most any state has experienced in a single day.

JULY 13 – The media reports that at least 5.4 million Americans have lost their health insurance during the pandemic.

JULY 13 – In an apparent attempt to undermine Dr. Fauci’s credibility, a White House official releases a statement saying that “several White House officials are concerned about the number of times Dr. Fauci has been wrong on things.”

JULY 17 – India reports one million coronavirus cases and 25,000 deaths. Researchers at MIT estimate that by the end of 2021, India could have the world’s worst outbreak.

JULY 17 – Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu announces new restrictions on gyms, restaurants and beaches.

JULY 19 – During a Fox News interview, President Trump again asserts COVID-19 is going to disappear, “I think we’re gonna be very good with the coronavirus. I think that at some point that’s going to sort of just disappear.”

JULY 20 – U.K.’s Oxford University COVID-19 vaccine shows positive results in first phase of human trials.

JULY 21 – European Union leaders agree on a $857 billion spending package to rescue their economies from ravages of COVID-19.

JULY 21– At his first coronavirus-related news conference in weeks, President Trump admits that COVID-19, “will probably, unfortunately, get worse before it gets better. Something I don’t like saying about things, but that’s the way it is.”

JULY 23 – U.S. surpasses 4 million reported coronavirus cases

JULY 23 – Trump cancels Republican convention activities in Jacksonville.

JULY 30 – Second-quarter GDP plunges by worst-ever 32.9% amid virus-induced shutdown.

JULY 30 – Herman Cain succumbs to COVID-19.

AUGUST

AUGUST 3 – Trump criticizes Deborah Birx after she warns the U.S. that the coronavirus outbreaks are “extraordinarily widespread.”

AUGUST 5 – Twitter temporarily restricts the Trump campaign’s ability to tweet false COVID-19 claims.

AUGUST 6 – U.S. records more than 52,000 new COVID-19 cases and 1,388 virus-related fatalities.

AUGUST 6 – Ohio Gov. Mike DeWine tests positive for the coronavirus.

AUGUST 26 – Under pressure from the White House, the CDC issues new guidance saying that people who do not exhibit symptoms after being exposed to someone with coronavirus, “do not necessarily need a test.”

SEPTEMBER

SEPTEMBER 9 – Media reports revelations from Bob Woodward’s new book Rage that President Trump purposely minimized the dangers posed by the coronavirus: “I wanted to play it down. I still like playing it down because I don’t like to create panic,” Trump told Woodward.

SEPTEMBER 9 – “The president never downplayed the virus,” White House press secretary Kayleigh McEnany tells the media.

SEPTEMBER 12 – Media reports that Michael Caputo and Paul Alexander, Trump-appointed officials at the Health and Human Services Department, pressured CDC to “revise, delay and even scuttle weekly reports on the coronavirus that they believed were unflattering to President Trump.”

SEPTEMBER 16 – Caputo takes a leave of absence from HHS after posting a Facebook video accusing government scientists of working to defeat President Trump. Alexander announces his departure from HHS.

SEPTEMBER 18 – Olivia Troye, a top adviser to Vice President Pence and member of the White House coronavirus task force, says the task force recognized by mid-February that the virus posed a big threat to the United States. “But the President didn’t want to hear that, because his biggest concern was that we were in an election year.”

SEPTEMBER 18 – CDC reverses its August 26 guidance and encourages people exposed to someone with coronavirus to get tested, whether they show symptoms or not.

SEPTEMBER 22 – The U.S. COVID-19 death toll passes 200,000, accounting for 21% of global deaths.

SEPTEMBER 25 – The number of confirmed U.S. cases passes seven million.

SEPTEMBER 28 – Twenty-one states report increases in cases as health experts warn of a surge in fall pandemic surge.