Some are concerned that subprime auto loans – which offer higher interest loans to riskier borrowers – pose a threat to the stability of the global economy in much the same way that the subprime mortgage market contributed to the Great Recession. Democratic presidential candidate Elizabeth Warren, in particular, has raised the warning flags as part of her campaign. But these worries are ill-founded and based on misleading data and faulty analogies.

In particular:

Risk-based pricing of auto loans appears to be working so far, keeping low-income borrowers in the market without driving up delinquencies or to low-income consumers, while not posing the same risk that the subprime mortgage market.

To purchase a vehicle, Americans with low or non-existent credit scores often use auto loans with higher interest rates than loans to prime borrowers. Some market watchers have indicated concern about “subprime” auto-loan trends and the potential for a crisis similar to the subprime mortgage crisis that heralded the last recession.

The subprime mortgages and the related mortgage-backed bonds remain the classic case of a poorly executed financial innovation. The initial impetus behind the idea was a good one. Housing is a key element of middle-class wealth, so expanding the system of mortgage finance to help lower-income households buy homes seemed like a positive. However, the subprime mortgages and bonds were designed in such a way that they assumed rising housing prices. When housing prices started to fall, the subprime mortgage system collapsed and contributed to the financial crisis.

Will subprime auto loans create the same problems? In a recent essay, Democratic presidential candidate Senator Elizabeth Warren raised the warning flag:

Auto loan debt is the highest it has ever been since we started tracking it nearly 20 years ago, and a record 7 million Americans are behind on their auto loans — many of which have similar abusive characteristics as pre-crash subprime mortgages1 .

Warren is not alone in her worries. In late 2016, for example, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency warned that auto-lending risk was increasing and that banks (and other investors in securitized assets) did not have sufficient risk-management policies in place. Fed Governor Lael Brainard pointed to subprime auto lending as an area of concern in a May 2017 speech, while analysts worried about “deep subprime” auto loans2. Some groups used the term “predatory” auto lending.3

But these concerns are misplaced. As we will show later in this paper, the statistic cited by Senator Warren does not reflect the current state of the auto loan market, as it includes old loans from much weaker economic times. Perhaps most fundamental to understanding the problem with drawing a parallel between the mortgage crisis and today is the fact that subprime mortgages and subprime auto loans are very different products.

Naturally, lower-income households with low credit scores or limited credit history may have fewer financial resources and be inherently riskier borrowers. Moreover, the fact that motor vehicles depreciate over time means that the collateral for the loan becomes less valuable.

Nevertheless, the ability to own a car and, therefore, access credit is crucial for this population. Risk-based pricing charges low- rated borrowers higher interest rates, but in return, offers them the opportunity to borrow money to buy a vehicle that might otherwise be financially inaccessible.

For many lower-income households, their vehicle is the single biggest asset they own.

While vehicles do not appreciate in value as homes do, vehicles are income-producing assets in the sense that they are often essential for commuting to work, especially in non-urban areas. As one report noted, “Owning a car is the price of admission to the economy and society in much of America.”4

In this paper, we analyze the auto loan market, paying particular attention to auto loans made to low-income Americans and to people with bad credit. We find that:

Risk-based pricing of auto loans appears to be working so far, keeping low-income borrowers in the market without driving up delinquencies or threatening the financial system. We conclude that the subprime auto loan market is beneficial to low-income consumers, while not posing the same risk that the subprime mortgage market did before the financial crisis. While it will be instructive to observe subprime auto loan trends going forward, current trends do not indicate significant instability concerns in this market.

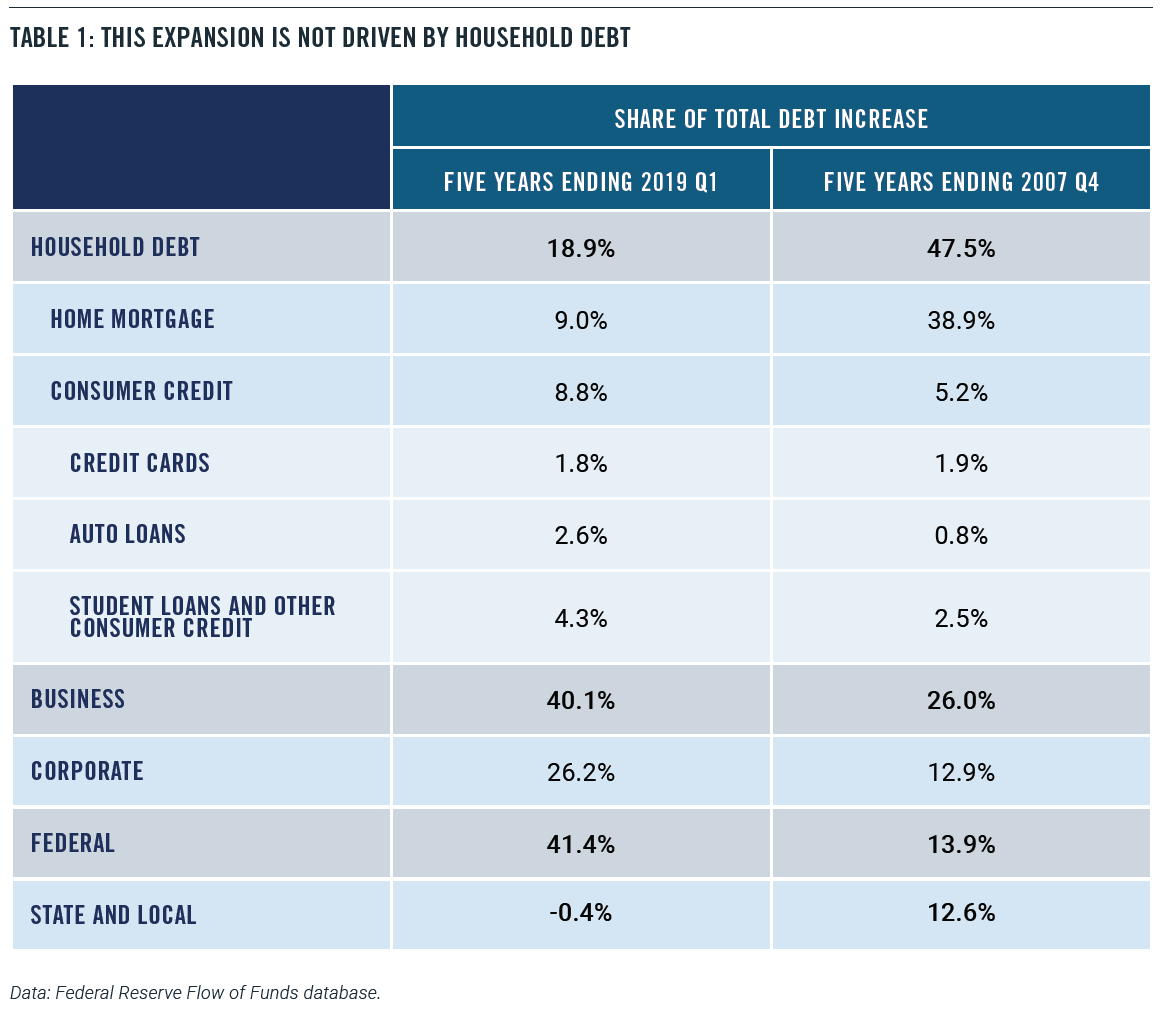

Recent patterns in debt accumulation are very different from those that preceded the financial crisis and Great Recession. Non-mortgage consumer credit – including auto loans, credit cards, and student debt – has risen by $900 billion over the past five years, according to Federal Reserve data. While that figure sounds substantial, that increase amounts to less than 9 percent of the total increase in domestic nonfinancial debt – that is, all debt except borrowing by financial institutions. The rise in consumer borrowing is dwarfed by the increase in business debt ($4.1 trillion) and federal debt ($4.2 trillion) over the same period. Those two categories together account for 82 percent of the increase in domestic nonfinancial debt (Table 1). The leading contributors to business debt growth are mortgages and corporate bonds.

Indeed, businesses have taken the greatest advantage of low-interest rates. Nonfinancial corporations have almost doubled their outstanding corporate bonds since the end of 2007 when the last recession started. Meanwhile, household debt has risen by only 10 percent.

Taking home mortgages into account, households have only accounted for 19 percent of the increase in domestic nonfinancial debt since 2014. By contrast, in the five years leading up to the Great Recession, households accounted for 48 percent of the debt increase. In other words, the financial boom in the pre-recession years was heavily driven by household borrowing, while households have only contributed a small portion to the current debt increase.

A skeptic could argue that, given derivatives and financial engineering, it’s possible for a relatively small portion of the debt market to drive an outsize increase in risk for the whole system. Indeed, that’s what happened ahead of the 2008 financial crisis. In May 2007, then-Chairman of the Federal Reserve Ben Bernanke famously said, “We believe the effect of the troubles in the subprime sector on the broader housing market will be limited, and we do not expect significant spillovers from the subprime market to the rest of the economy or to the financial system.”5 At the time, the value of subprime mortgages was about $1.3 trillion, which was only 10 percent of the mortgage market and an even smaller share of total borrowing. Bernanke and other policymakers figured that the problems in subprime mortgages could be easily contained.

What Bernanke and others failed to reckon with, however, was how the subprime mortgages had been designed to make sense only in a rising real estate market. Subprime mortgages were constructed effectively to subsidize interest rates with the possibility of appreciation. These financial instruments would offer low upfront rates that enabled lower-income borrowers to qualify. When the teaser rates eventually reset to much higher levels, the assumption was that the borrower could refinance into a new mortgage.

Moreover, the subprime mortgages were then securitized and used to build complicated financial derivative products. And when the subprime mortgages failed because of declining home prices, so did the derivatives. In other words, problems in a relatively small financial sector could be amplified and have a much larger effect on the rest of the economy.

Despite this concern, there is evidence to suggest that subprime auto lending is not a substantial risk to the broader economy. Auto loans are only 7.4% of household debt, which is the 40-year historical average.6 Moreover, the auto asset-backed securities (ABS) market is likewise dwarfed by the mortgage-backed securities (MBS) market. As of the second quarter of 2019, there was a mere $264 billion in auto-related securities, which included only $55 billion in subprime auto securities. By comparison, the amount of outstanding mortgage-related securities came to almost $10 trillion.7

Further, subprime auto loans don’t work the same way that subprime mortgage loans did in the pre-crisis era. Cars and trucks depreciate steadily over time, so the value of the collateral diminishes. That means lenders can’t afford to offer teaser rates, or excessive levels of negative equity, to buyers with low credit scores. They must charge higher rates, properly pricing risk. As one article put it, “the very nature of a real estate loan is very different from an auto loan. Real estate is an investment that typically appreciates over time. During the bubble years, consumers and lenders falsely believed appreciation would bail them out from poor judgment. Vehicles, on the other hand, depreciate. There is no false hope of higher values in the future to bail out a borrower or a lender.”8

Despite the relatively small role that consumer debt is playing in the current debt expansion, some people can’t shake the idea that Americans are over-spending and over-borrowing to maintain a particular lifestyle. Consider this quote from an April 2019 piece from Business Insider:

The fact that America’s top-selling vehicle — a Ford truck with a price starting at nearly $30,000 – and many like it cost nearly half the median household income hasn’t stopped people from buying them and hasn’t stopped lenders from facilitating loans.9

Over the past five years, the price of new motor vehicles has risen by only 1.1 percent, according to estimates by the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA).10 By contrast, the overall price level of consumer goods and services have risen by 6.7 percent over the same stretch.11 In other words, the relative price of new motor vehicles has fallen over this period.

Not surprisingly, the share of consumer spending on new and used vehicles has fallen as well. In 2000, 5.4 percent of consumer spending went to purchases and leases of new and used vehicles. Today, that share is down to 3.6 percent (Figure 1).12

The BLS Consumer Expenditure Survey tells the same story. In 2000, motor vehicle purchases and finance charges amounted to 9.7 percent of household outlays. As of 2018, the last year for which full data is available, the share of vehicle purchases and finance charges fell to only 6.7 percent of household outlays.13 In part, this decline may represent a lengthening of the term of auto loans.14 (These figures would not be changed much by including automobile lease-related payments, which amount to about 10 percent of automobile purchase-related payments in 2018.)

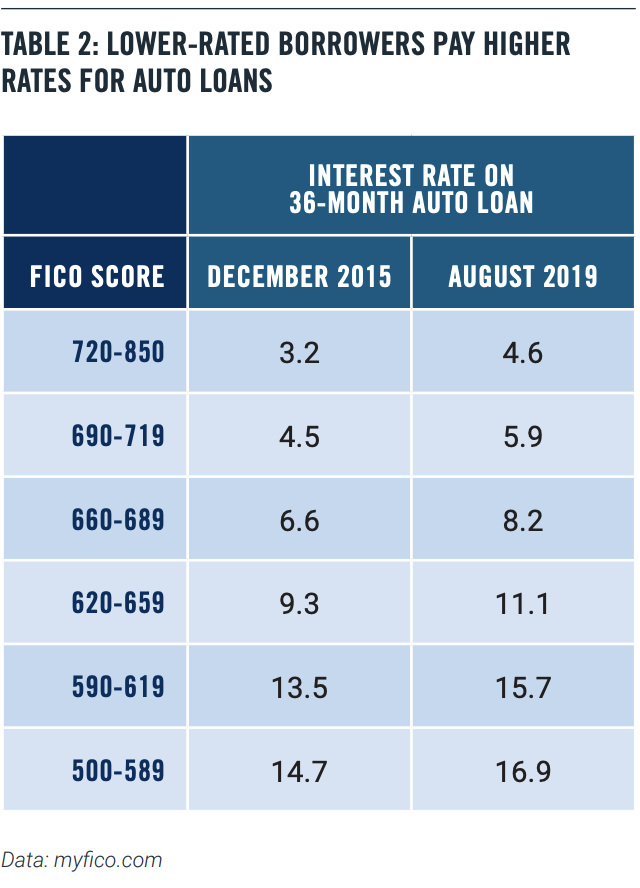

It’s not surprising that lower-rated borrowers pay more for their auto loans. Table 2 below shows interest rates for a 36-month new car loan at different credit rates for December 2015, which was close to the bottom of the credit cycle, and August 2019 (Table 2).

We can see that rates have risen for all credit-rating levels, but more so for the low-rated borrowers.

This risk-based pricing means that low-rated borrowers are not frozen out of the auto loan market. That’s good news, since, in many parts of the country, a car or truck is a necessity, even for low-income households. There is little or no public transit outside of densely populated urban areas, and ride-sharing services are not viable alternatives in many places. So, it is unsurprising that the share of low-income (the bottom quintile) households with a vehicle hold steady at 66 percent in both 2000 and 2018.

At the same time, low-income households saw motor-vehicle purchase and finance taking a smaller share of their budgets. In the bottom quintile of pre-tax income, motor vehicle purchases and finance charges fell from 8.5 percent of household budgets in 2000 to 4.9 percent in 2018 (Figure 2), a drop of almost four percentage points.15

Similar data from the New York Fed’s Household Debt and Credit Report confirm that low-income households are not being uniquely stressed financially by automobile borrowing. Figure 3 shows the share of all auto loan originations that are going to low-rated borrowers (with a Riskscore of less than 620). Before the financial crisis, about 30 percent of new auto loans were going to low-rate borrowers, a startlingly high percentage. That share fell to 20 percent after the crisis and shows no signs of rising (Figure 3).16

The biggest piece of negative news has come from the New York Federal Reserve’s well-publicized finding in February 2019:

…(T)here were over 7 million Americans with auto loans that were 90 or more days delinquent at the end of 2018. That is more than a million more troubled borrowers than there had been at the end of 2010 when the overall delinquency rates were at their worst since auto loans are now more prevalent.18

This startling number, while impressive, simply doesn’t mean what it seems to suggest. This figure includes anyone who still has an old, bad auto loan on their credit record, even if the loan was made and written off years earlier.19 In fact, even after the lender writes off the loan, the loan servicer could continue to report the account to the credit bureaus.

The recent economic history of the United States helps to explain this figure. The number of nonfarm jobs did not return to pre-recession levels until 2014, while the employment-population ratio for Americans with a high school diploma but no college did not bottom out until 2015. As a result, today’s subprime borrowers are carrying around bad loans from the days when the labor market for less-educated workers was still struggling.

Indeed, in an August 2019 blog item, New York Fed economists recommend that anyone interested in the current performance of debt should look at the transition into delinquency- that is, a chart such as Figure 4.20 And by that measure, auto loans are doing far better than in the pre-recession years.

In the event of a recession or a significant economic slowdown, auto loan delinquencies will predictably rise. Subprime auto borrowers, who are more likely to have fewer resources, will be likely to fall behind in their payments when times turn bad.

Nevertheless, a careful look at the data does not suggest that either the origination of subprime auto loans or the exposure of the broader macroeconomy to the auto loan market is a cause for concern. In particular, the subprime auto-loan market looks nothing like the mortgage market before the Great Recession.

Newly delinquent auto loans, as a percentage of current balances, have been falling over the past two years, and the fact that a record number of Americans have a bad auto loan on their credit record is a testimony to economic history more than current loan practices and economic conditions, particularly given the rapid rise in total car sales during this period.

Indeed, risk-based pricing in the auto loan market appears to be supplying a steady flow of credit to low-rated borrowers without imposing excess stress on the financial system.

Michael Mandel is Chief Economic Strategist of the Progressive Policy Institute.

Douglas Holtz-Eakin is President of the American Action Forum.

Thomas Wade is Director of Financial Services Policy of the American Action Forum.