2020 31%

2019 29%

2012 26%

2002 26%

1992 25%

Here is J.M. Keynes, looking back from 1919 at the “globalized” world of the 1910s, from the perspective of a wealthy (male) Londoner:

“[For] the middle and upper classes, life offered, at a low cost and with the least trouble, conveniences, comforts, and amenities beyond the compass of the richest and most powerful monarchs of other ages. The inhabitant of London could order by telephone, sipping his morning tea in bed, the various products of the whole earth, in such quantity as he might see fit, and reasonably expect their early delivery upon his doorstep; he could at the same moment and by the same means adventure his wealth in the natural resources and new enterprises of any quarter of the world, and share, without exertion or even trouble, in their prospective fruits and advantages; or he could decide to couple the security of his fortunes with the good faith of the townspeople of any substantial municipality in any continent that fancy or information might recommend.”

Taking up his themes of easy and uninterrupted flows of investment and trade a century later, with some employment focus as against Keynes’ investor-and-consumer viewpoint–

The U.N. Conference on Trade and Development’s annual “World Investment Report”, reports that annual cross-border “foreign direct investment” flows have varied between $1 trillion and $2 trillion over the last decade, with the U.S. in most years both the largest source and recipient. Last year was a typical example, with the U.S. receiving $367 billion of the worldwide $1.6 trillion in total inbound FDI flows, and sending out $404 billion.

Reporting each year on these flows’ real-world manifestations, the Commerce Department’s Bureau of Economic Analysis publishes figures on international businesses’ employment, investment stocks, employment, R&D, payrolls, and so forth in the United States and abroad. Their most recent editions cover the year 2020 and find U.S. “affiliates” of foreign-based firms employing 8.6 million workers, and U.S.-based firms with overseas operations employing 28.4 million people in the U.S. (along with 14 million overseas). Together, then, internationally operating businesses employed 37 million private-sector workers, or 31% of the COVID-depressed 120 million total. Two bits of perspective on this:

(1) Economic role: The “multinational’ firms — both U.S. “parents” and foreign “affiliates” — are particularly employers in manufacturing (10 million of 12.2 million), retail (10 million of 17 million, and information industry (2.0 million of 2.7 million). They are also very prominent in private-sector science, together accounting for $430 billion of 2020’s $717 billion in U.S. R&D spending. (U.S.-based firms did most of this at $361 billion, not counting $59 billion in overseas R&D; U.S.-based affiliates of foreign firms contributed $73 billion in U.S.-based R&D. And they account for about two-thirds of U.S. goods trade, including $1.08 trillion of 2020’s $1.66 trillion in exports, and $1.43 trillion of the $2.35 trillion in imports.

(2) Over time: At least with respect to employment, multinationals’ role in U.S. economic life has been pretty stable over the last generation. The 31% share of employment in 2020 is at the high end of BEA’s records, but this is mainly because, before COVID vaccines, employment was especially depressed in industries with fewer multinationals, such as restaurants, hotels, beauty shops, and other small services businesses. Over the last 30 years, the “multinational” share of U.S. employment has varied between 25% and 29% of private-sector workers – or, to cite a few specific years, 26% of the 121 million private-sector workers in 2012, 26% of the 108 million in 2002, and 25% of the 90 million in 1992. Over this time, U.S.-based multinationals have added about 11 million employees in the U.S. (17.5 million then, 28.4 million in 2020), while simultaneously adding 10 million overseas. International firm employment in the U.S. has grown at a slightly faster pace in percentage terms but less sharply in total numbers, rising by about 80% from 4.8 million in 1992 to 8.6 million in 2020.

Lots of money and research, the various products of the world freely available, employment rising at typically modest but positive gradations each year. All this may feel a bit reassuring, as “geopolitics” grows steadily more menacing, and international institutions fray at the edges — but it also makes Keynes’s close, as he reflects on how fragile the apparent calm and stability of his own recent past were, especially unsettling:

“[H]e [the hypothetical upper-middle class Londoner, probably referring to himself] regarded this state of affairs as normal, certain, and permanent, except in the direction of further improvement, and any deviation from it as aberrant, scandalous, and avoidable. The projects and politics of militarism and imperialism, of racial and cultural rivalries, of monopolies, restrictions, and exclusion, which were to play the serpent to this paradise, were little more than the amusements of his daily newspaper, and appeared to exercise almost no influence at all on the ordinary course of social and economic life.”

More from BEA:

U.S.-based multinationals.

… and earlier reports on American multinationals 2004-2021, with a link to an archive dating back to 1982.

International firms in the United States.

… and the counterpart set of reports on foreign investment in the United States.

International perspective:

UNCTAD’s World Investment Report 2022.

Sources and destinations:

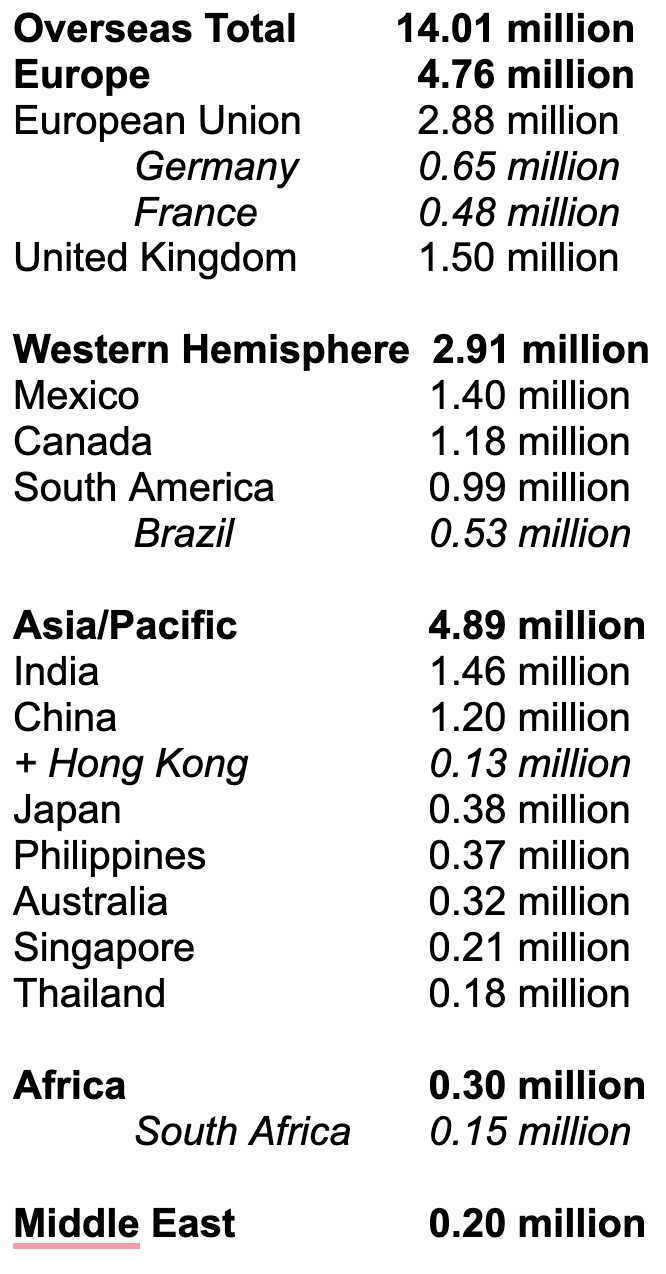

BEA’s figures look at U.S. private-sector investment abroad as well as multinationals operating here, with some detail on destinations for U.S. investment and the ownership of investment here. As both a destination and a source, Europe is the main partner and Canada is disproportionately large. By value (“investment stock”), Europe is home to $4 trillion of $6.5 trillion in U.S. FDI abroad (2020), with the U.K. at $1.0 trillion, EU members $2.7 trillion, and Switzerland, Norway, Iceland, and Turkey together $0.25 trillion. Latin American countries are at $0.25 trillion, led by Mexico at $110 billion; Asia and the Pacific are at $960 billion, topped by Singapore at $294 billion, Australia at $167 billion, and Japan and China both around $118 billion. Measured by jobs, though, U.S. firms employ about as many people in Asia as in Europe. A table of U.S. overseas employment by region:

Looking the other way, European firms are likewise the main international employers in the United States, at 5 million jobs or about 60% of the 8.6 million total. By country, U.K. firms led at 1.2 million, followed by Japanese at just above 1 million, Canadians just below, Germans at 885,000, French at 740,000, and Dutch at 569,000. Japanese firms employed a bit more than 1 million Americans, second only to the Brits; Canadians just a bit less at 940,000. Chinese firms, though receiving much attention and publicity, were modest employers of Americans at 153,000; Mexicans were at 89,000, and Indians 73,000.

And the ghost at the banquet:

Keynes’ The Economic Consequences of the Peace (1919).

Ed Gresser is Vice President and Director for Trade and Global Markets at PPI.

Ed returns to PPI after working for the think tank from 2001-2011. He most recently served as the Assistant U.S. Trade Representative for Trade Policy and Economics at the Office of the United States Trade Representative (USTR). In this position, he led USTR’s economic research unit from 2015-2021, and chaired the 21-agency Trade Policy Staff Committee.

Ed began his career on Capitol Hill before serving USTR as Policy Advisor to USTR Charlene Barshefsky from 1998 to 2001. He then led PPI’s Trade and Global Markets Project from 2001 to 2011. After PPI, he co-founded and directed the independent think tank Progressive Economy until rejoining USTR in 2015. In 2013, the Washington International Trade Association presented him with its Lighthouse Award, awarded annually to an individual or group for significant contributions to trade policy.

Ed is the author of Freedom from Want: American Liberalism and the Global Economy (2007). He has published in a variety of journals and newspapers, and his research has been cited by leading academics and international organizations including the WTO, World Bank, and International Monetary Fund. He is a graduate of Stanford University and holds a Master’s Degree in International Affairs from Columbia Universities and a certificate from the Averell Harriman Institute for Advanced Study of the Soviet Union.

Read the full email and sign up for the Trade Fact of the Week