2022 $1.20 trillion

2020 $0.90 trillion

2016 $0.65 trillion

2000 $0.32 trillion

How does the Trump-era agenda hold up six years later, when matched against its officials’ trade-balanced centered critiques of their predecessors and goals for their own program?

Each February, the U.S. Trade Representative Office puts out a report entitled “The President’s Trade Agenda,” which sets out Administration goals for the coming year. The 2017 edition cited a U.S. global trade balance statistic as proof that earlier administrations got things wrong:

“In 2000, the U.S. trade deficit in manufactured goods was $317 billion. Last year [i.e. 2016] it was $648 billion – an increase of 100 percent.”

The next edition, in 2018, used “bilateral” trade balance with Mexico — i.e. country-to-country, subtracting the value of U.S. exports to Mexico from the value of imports from Mexico — to claim failure for the North American Free Trade Agreement and set a goal for the renegotiated “USMCA”:

“[O]ur goods trade balance with Mexico, until 1994 characterized by reciprocal trade flows, almost immediately soured after NAFTA implementation, with a deficit of over $15 billion in 1995, and over $71 billion by 2017. … USTR has set as its primary objective for these renegotiations – to improve the U.S. trade balance and reduce the trade deficit with the NAFTA countries.”

How does this hold up six years later? Before turning to the bleakly comical answers, an econ. note and a couple of stat. correctives:

(1) Standard Econ 101 equations show that a country’s trade balance always matches the difference between its savings and its investment. Since the mid-1970s, Americans have been investing more than we save; ergo, trade deficits. The orthodox view is that while very high trade deficits can arouse alarm as indicators of unsustainable booms, the appropriate response is fiscal contraction and long-term measures to raise savings rates (and contrariwise, expansion and higher consumer purchasing in surplus countries). One corollary of this is that trade policy measures like tariffs or FTAs won’t much affect overall balances, and shouldn’t really be judged on a balance basis. A second is that a program like the Trump administration’s — business tax cuts which will (barring some offsetting rise in family or corporate savings) lower the national savings rate and possibly raise investment, plus higher government spending which will (barring some offsetting collapse of private-sector investment) raise national investment rates will naturally create a higher trade deficit. (Or lower surplus for countries in surplus.) The Trump administration’s evident hypothesis was that this basic equation is in error, and a combination of tariffs and negotiated purchasing commitments, rules of origin, efforts of will, and so forth, would force the plus and minus signs to change.

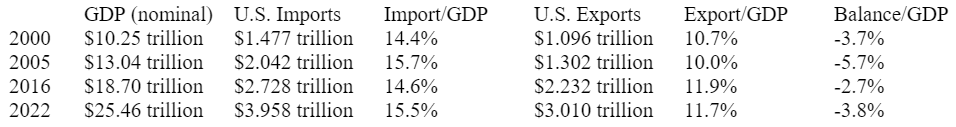

(2) Statistically, the best way to compare balances across time (and especially over decades) is to look at “trade balance relative to GDP,” rather than “nominal” dollar totals which don’t account for inflation or the scale of trade relative to the economy. By this measure, the U.S. trade deficit has averaged 2.7% of GDP since 1982, with lows of 0.5% in 1991 and 1992 and highs of 5.7% in 2005 and 2006. The 2016 level was 2.7% of GDP, exactly the 40-year average and a bit below the 3.7% of GDP of 2000 and the 3.0% of GDP in 1987.

(3) Less consequentially, U.S. goods trade with Mexico might be termed “characterized by balanced trade” across the entire 1970-1990 stretch of time, but oscillated with growth trends and energy prices from a surplus (from a U.S. perspective) in the 1970s, to deficits from 1982 through 1990, and then briefly surplus during the Mexican boom/U.S. recession in 1991-1993.

These points duly noted, here are the 2022 figures analogous to those in the 2017 and 2018 President’s Trade Agenda reports:

Overall and manufacturing balances: The largest measurement of trade balance is the (exports of goods + services) – (imports of goods and services). At 2.7% of GDP ($480 billion) in 2016, this reached 3.0% of GDP ($845 billion) in 2021, and 3.8% of GDP ($948 billion) in 2022. The manufacturing deficit was $892 billion in 2020, $1.06 trillion in 2021, and $1.20 trillion in 2022. Thus it nearly doubled the $648 billion nominal-dollar figure cited as evidence of debacle in 2017.

Bilateral balances: The U.S.-Mexico goods trade balance with Mexico, two years into the USMCA, was -$120 billion in 2022, nearly double the 2017 figure used to illustrate the need to renegotiate the NAFTA. The balance with Canada, a $16 billion deficit in 2017, was $80 billion in deficit as of 2022. USMCA may well have some advantages over the NAFTA — new digital material, labor, and environmental coverage, and so on – but with respect to balance the Trump negotiators look to have over-reached. Even the China goods deficit, at $383 billion in 2022, was well above the pre-“301” tariff of $347 billion of 2017.

In sum, not quite what the policies’ authors predicted, and a bit of vindication for the economists who (a) thought use of trade balance as a success-meter was a mistake in general, and (b) based on policy and growth trends, predicted an outcome a lot like the one that actually happened.

The Trump administration’s 2017 Executive Order on “Omnibus Report on Significant Trade Deficits” asked the U.S. Trade Representative Office and the Commerce Department to write up a report on trade balances with most major U.S. trading partners. This was never released:

Data:

The Census Bureau’s U.S. monthly trade data

… and imports, exports, and bilateral balances for the U.S. with individual countries, back to the mid-1980s

… and for the big picture, U.S. worldwide annual exports, imports, and balances from 1960-2022 on one convenient page

As noted above, a better way to put trade flows and balances in context is relative to GDP. A quick run-down of imports, exports, and balances in 2016 and 2022, with 2000 and peak-deficit year 2006 added for context.

What Happened?

Why the upward turn since 2016? Tax policy is the logical suspect. Three of four big upward ratchets in U.S. trade deficits since the 1970s followed tax-cut bills: one in 1981, another in 2001, and the third in 2017. Bills of this sort typically bring somewhat higher government deficits (“dissavings”), which mean an overall drop in national savings unless offset by higher family or business saving. All else equal, by virtue of the “savings-investment = trade balance” identity, trade deficits rise.

The main balance effects of the Trump-era tariffs are likely (a) shifting some of the overall U.S. deficit from China to Vietnam, Mexico, and some other mid-income countries, and (b) also probably, though less certainly, concentrating the deficit more in manufacturing than had been the case before 2017. Trump-era tariffs on steel, aluminum, and Chinese goods fall heavily on industrial inputs — metals, auto parts, electrical converters, etc. — and require U.S. manufacturers and farmers to absorb extra costs. The likely result is some marginal loss of competitiveness for exporters trying to sell to foreign buyers and for firms competing against imports at home, pushing a larger share of the overall U.S. deficit into manufacturing, reducing the erstwhile agricultural surplus, and accelerating the shift of energy from deficit to surplus.

The Two Reports

The 2017 President’s Trade Agenda.

… and the 2018 followup (with an extraordinary claim that the 2017 tax bill “has the potential to reduce the U.S. trade deficit by reducing artificial profit shifting”).

Ed Gresser is Vice President and Director for Trade and Global Markets at PPI.

Ed returns to PPI after working for the think tank from 2001-2011. He most recently served as the Assistant U.S. Trade Representative for Trade Policy and Economics at the Office of the United States Trade Representative (USTR). In this position, he led USTR’s economic research unit from 2015-2021, and chaired the 21-agency Trade Policy Staff Committee.

Ed began his career on Capitol Hill before serving USTR as Policy Advisor to USTR Charlene Barshefsky from 1998 to 2001. He then led PPI’s Trade and Global Markets Project from 2001 to 2011. After PPI, he co-founded and directed the independent think tank Progressive Economy until rejoining USTR in 2015. In 2013, the Washington International Trade Association presented him with its Lighthouse Award, awarded annually to an individual or group for significant contributions to trade policy.

Ed is the author of Freedom from Want: American Liberalism and the Global Economy (2007). He has published in a variety of journals and newspapers, and his research has been cited by leading academics and international organizations including the WTO, World Bank, and International Monetary Fund. He is a graduate of Stanford University and holds a Master’s Degree in International Affairs from Columbia Universities and a certificate from the Averell Harriman Institute for Advanced Study of the Soviet Union.

Read the full email and sign up for the Trade Fact of the Week