In a statement released after the latest consumer price report, President Biden remarked on the “meaningful reduction in headline inflation” but indicated that there was still “more work to do, with price increases still too high and squeezing family budgets.”

In particular, the Biden Administration wants to protect consumers by identifying markets where sellers are taking advantage of the pandemic and supply chain snarls to raise prices. That’s a great plan.

At the same time, it’s also important to recognize and acknowledge those industries where price increases have been moderate and restrained.

In that spirit, we examine the inflation performance of the digital sector of the economy, encompassing tech, ecommerce, broadband, and related industries. These companies have come under fire for a variety of different reasons, some deserved, some not.

In this blog item we will show, based mainly on government data, that digital companies are helping hold down inflation at a time when prices are soaring in many other parts of the economy. For the Democrats and the Biden Administration, this is a success story they can build on.

The Historical Perspective

We’re used to computers getting cheaper over time, as they become more powerful and versatile. The Internet opened up entirely new dimensions of free websites, with everything from recipes to news to maps and directions. Long distance phone calls have effectively become free. Broadband networks, both wired and wireless, have become faster, connecting almost every part of the country. Content has become more varied and cheaper, at the same time.

There is no doubt that technology has been a profoundly disinflationary force historically. But what about today? The GDP inflation rate was 4.6% in the year ending with the third quarter of 2021. That’s a big jump from the 1.7% GDP inflation rate in the third quarter of 2019, before the inflation. How much of that acceleration is coming from the tech sector?

The answer is, precisely none. As part of its calculation of GDP, the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) calculates price changes by industry. It turns out that inflation rates in four key digital industries are not only negative but falling (Table 1). For example, the inflation rate in the “data processing, internet publishing, and other information services” industry fell from +0.5% in 2019 to -1.1% today.

The same is true for the other three key digital industries. Digital is still following the historical trends of being disinflationary.

| Table 1. Digital is Still Disinflationary

(change in value-added prices) |

||

| year ending | ||

| 2019Q3 | 2021Q3 | |

| Computer and electronic product manufacturing | -0.1% | -1.8% |

| Broadcasting and telecommunications | -0.9% | -2.6% |

| Data processing, internet publishing, and other information services | 0.5% | -1.1% |

| Computer systems design and related services | -0.2% | -2.8% |

| Gross domestic product | 1.7% | 4.6% |

| Data: BEA, based on Table TVA104-Q | ||

Ecommerce and inflation

Let’s now consider ecommerce prices in particular. As of the third quarter of 2021, ecommerce accounted for 13% of retail sales according to the Census Bureau. That’s back on the long-term trend line after a temporary pandemic-induced jump.

But still, there’s an important question: Why isn’t ecommerce a bigger share of retail sales, given how much we are all shopping online? One reason might be that online prices tend to rise at a slower rate than brick-and-mortar prices, according to the available evidence. Indeed, government data shows that the long-term trend of ecommerce has been and continues to be disinflationary.

Consider this: The BLS measures changes in gross margins in all major retail industries, where the margin is defined as the selling price of a good minus the acquisition price for the retailer. Margins include all costs, such as labor, capital, and energy, plus profits, taking into account gains in productivity. A slower rise in margins translates directly into less inflation for consumers, all other things being equal.

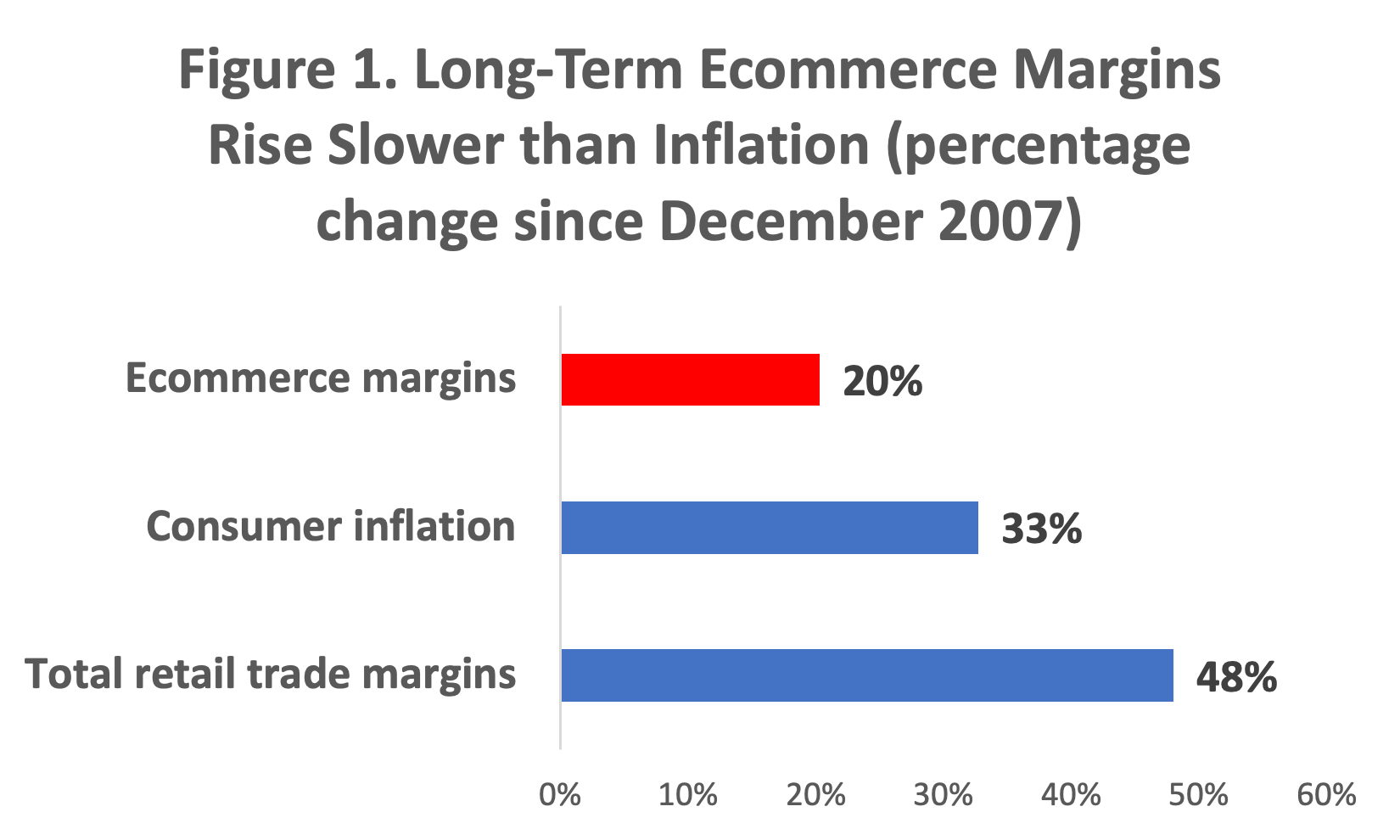

Between December 2007 and December 2021—a 14-year stretch that included the financial crisis, the long boom, and the pandemic—margins in the electronic shopping industry rose by 20%, according to BLS data (Figure 1). Over the same stretch, consumer prices rose by 33%. The implication: Ecommerce companies were accepting thinner margins in real terms, and passing those benefits onto consumers.

By comparison, the data for the overall retail industry has shown a much worse inflation performance, measured by margins. Margins for the total retail industry rose by 48% since December 2007, much faster than consumer inflation. As a result, real margins for the retail industry as a whole have risen, putting upward pressure on consumer prices.

By comparison, the data for the overall retail industry has shown a much worse inflation performance, measured by margins. Margins for the total retail industry rose by 48% since December 2007, much faster than consumer inflation. As a result, real margins for the retail industry as a whole have risen, putting upward pressure on consumer prices.

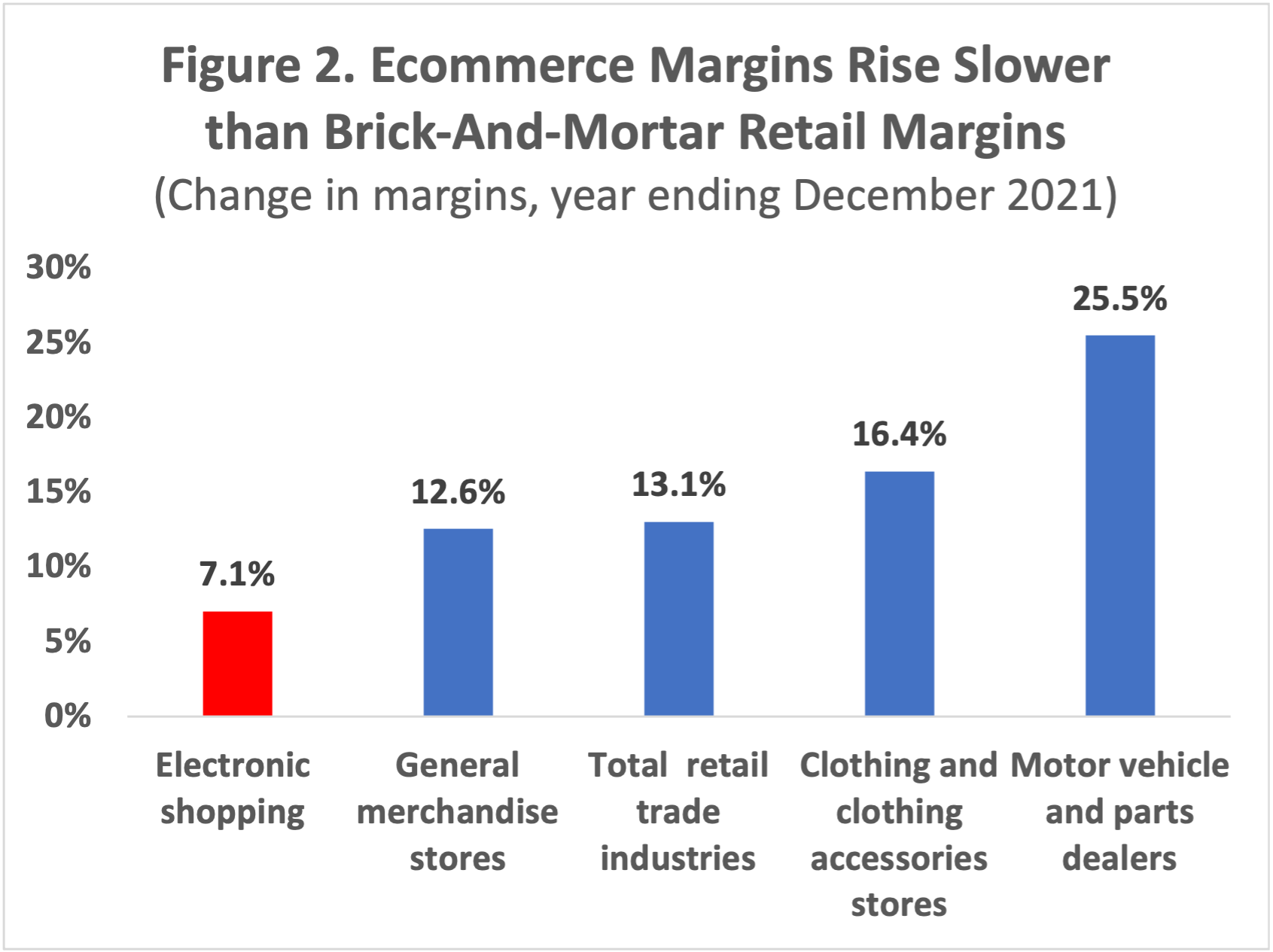

Now let’s look at the current situation. Even in today’s inflationary burst, ecommerce stands out as a force holding down margin increases compared to the rest of retail. In the year ending December 2021, overall retail margins rose by 13.1%. Meanwhile margins at general merchandise stores like warehouse outlets rose by 12.6%. Margins at auto dealers and other auto-related retailers rose by a stunning 26%, far outpacing inflation

By comparison, over the past year, ecommerce margins only rose by 7.1%, about the rate of inflation (Figure 2). These results are completely consistent with the economic literature, which mostly concludes that prices for online goods rise slower than the prices for comparable goods sold offline. A 2018 paper co-authored by Austan Goolsbee (CEA head under President Obama) found that online inflation was more than a full percentage point lower than the corresponding official consumer price index. Sometimes the difference can be much greater. The latest “Digital Price Index” report issued by Adobe shows that the price of furniture and bedding sold online rose by 3% in the year ending November 2021. Meanwhile the official CPI for furniture and bedding, including all brick-and-mortar stores, rose by 12%,

Moreover, the slow growth of ecommerce margins came at the same time that ecommerce fulfillment centers were dramatically boosting employment and pay. Over the last year, the average hourly earnings for production and nonsupervisory workers in the warehousing industry rose by 19.4%. That covers the great majority of ecommerce fulfillment centers.

The ability to simultaneously hold down prices for consumers, reduce shopping time for households, and boost pay for workers, represents a rare win-win proposition. What could be better?

Smartphones, Telecom, and the Digital Economy

During the pandemic, the daily life of Americans has been supported by wired broadband and wireless networks, by content delivered to the home and to wireless devices such as smartphones. This Digital Economy has been essential for work, school, and social contacts in the midst of these bizarre years.

But equally important, the Digital Economy is also a low-inflation economy. While the price of old economy products like cars, clothing, and gasoline has been soaring, the inflation rate of digital goods and services like smartphones, video and audio services, wireless, and internet access has remained low.

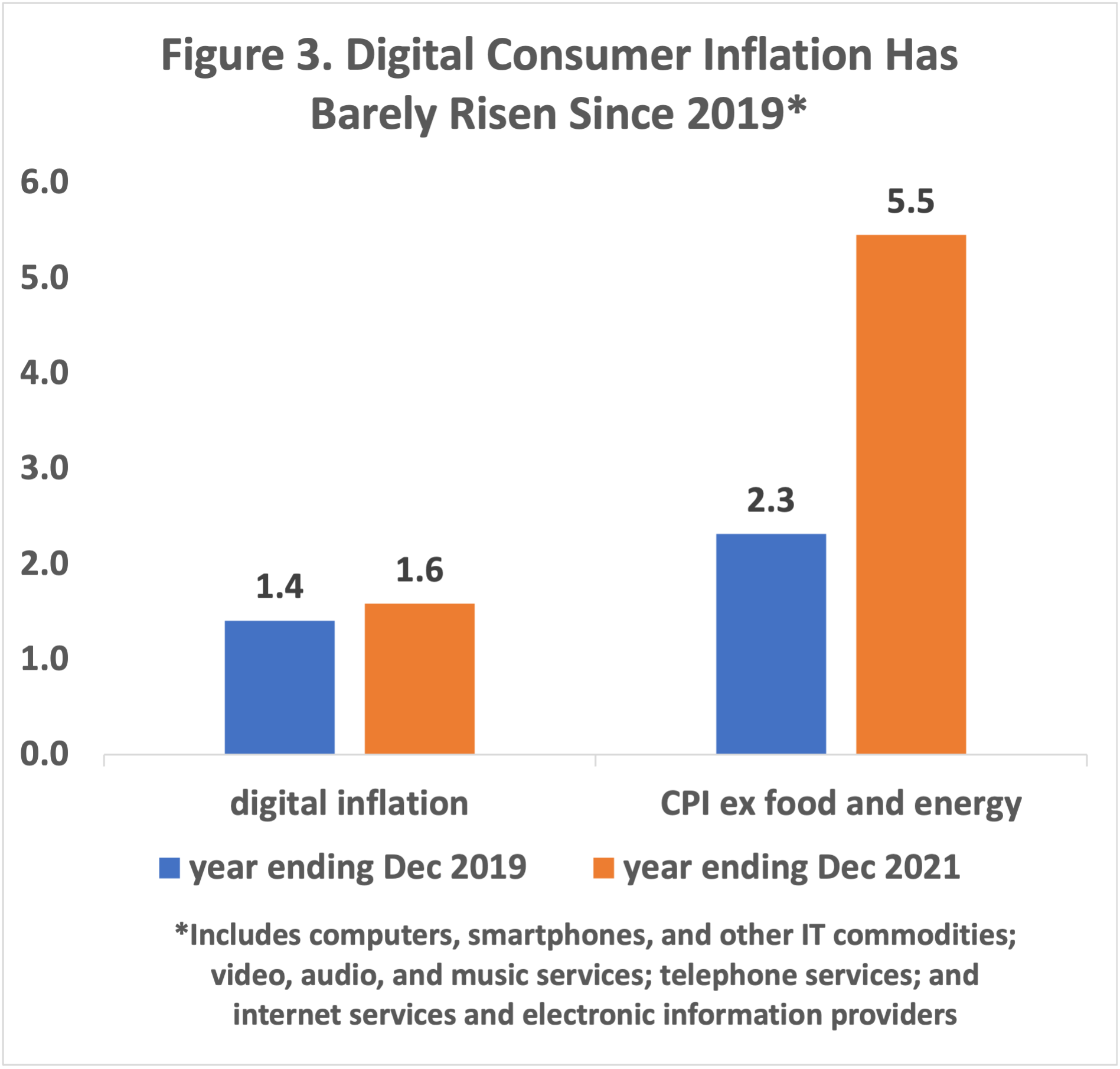

According to our analysis of BLS data, the digital consumer inflation rate was only 1.6% in the year ending December 2021, barely above the 1.4% rate in the year ending December 2019, before the pandemic started (Figure 3). This figure includes computers, smartphones, and other IT commodities; video, audio, and music services; telephone services; and internet services and electronic information providers. We use BLS spending shares to weight the components of the digital inflation rate.

Looking at individual items, the inflation rate for video and audio services, including cable and satellite television service, fell from a 3.1% rate in 2019 to a 2.6% rate in 2021. The inflation rate for telephone services, including wireless, went from 1.6% in 2019 to 0.7% in 2021. Perhaps most striking, the price of smartphones continued their relentless plunge in 2021, dropping in price by 14% after adjusting for quality.

By contrast, there was a huge jump in core consumer inflation, which went from 2.3% in 2019 to 5.5% in 2021. Note that even if some of the components of digital inflation are mismeasured, as some have argued, looking at the change over time should be more accurate if the size of the mismeasurement stays the same.

Tech Inflation

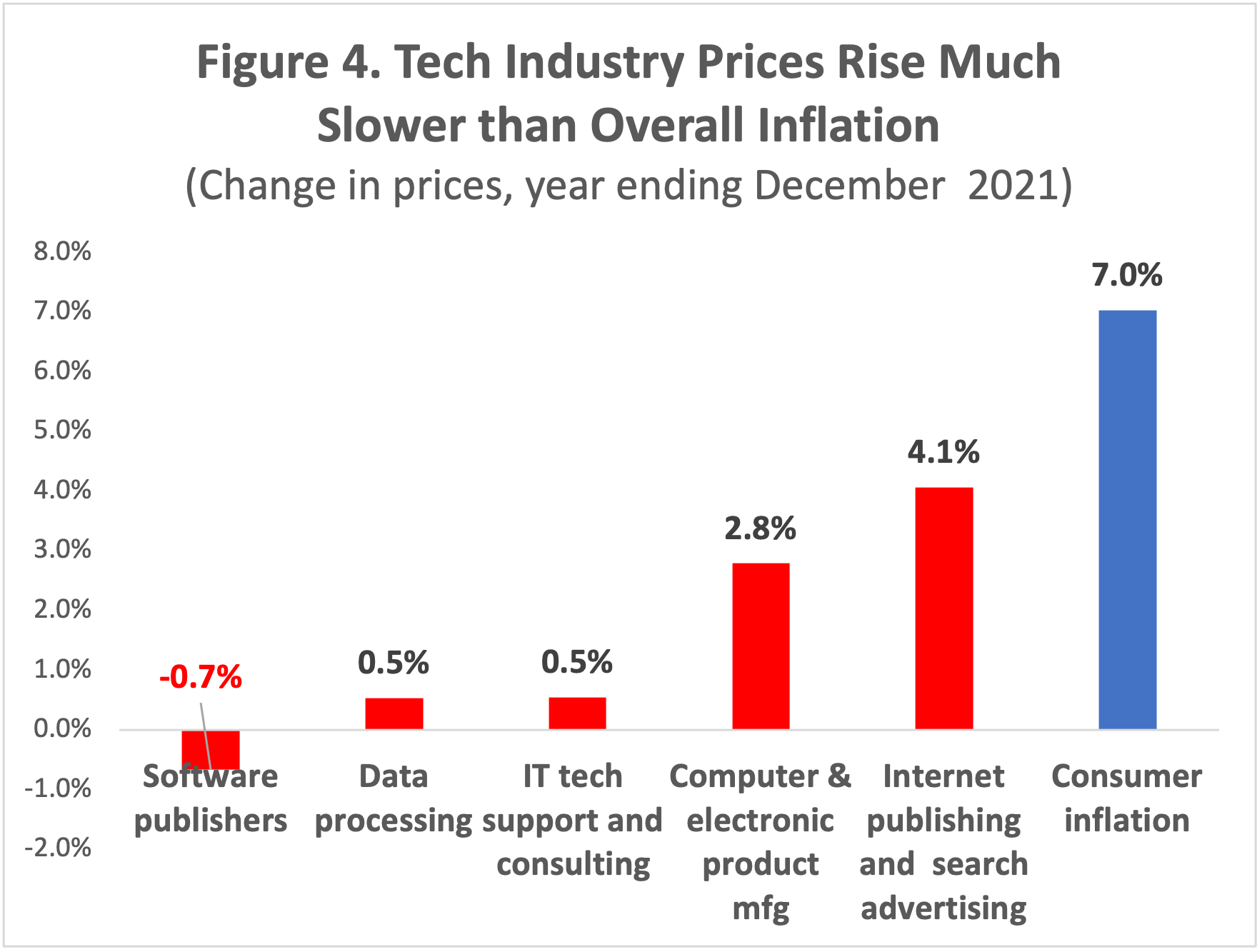

Here we drill down into inflation performance into various components of the tech sector, using data from the BLS Producer Price program. Figure 4 compares inflation in several tech-related industries with consumer inflation.

According to the BLS, prices for the software publishing industry fell by 0.7% in the year ending December 2021. Prices for data processing and IT support and consulting rose by a measly 0.5%. Computer and electronic product manufacturing prices rose by 2.8%. And the price of internet publishing and search advertising rose 4.1%, considerably slower than the overall consumer inflation rate. That means in real terms the price of internet publishing and search advertising has been getting relatively cheaper.

The App Economy

Finally, we come to the App Economy and the app stores. Arguably one of the great technological shifts of all time, the introduction of the Apple iPhone in 2007 and then the Apple App Store in 2008 created an entirely new model for delivering services to consumers conveniently and at a low price. It is clear that the App Economy is a profoundly disinflationary force.

The current price statistics do not break out app-relevant price measures, like the price of app downloads or in-app purchases, either from the consumer or app developer perspective. Nevertheless, a careful look at the structure of the pricing structure of the app stores suggests they are contributing to low inflation today.

App store pricing comes in two parts. First, both the Apple App Store and Google Play charge a nominal fee for registering for a developer account. Google Play charges $25 to register, an amount that hasn’t changed in years. Similarly, the Apple App Store charges an annual fee $99 for a basic developer membership, an amount that also hasn’t changed in the U.S. for years (there are a variety of exemptions). As a result, the inflation-adjusted fee has fallen substantially over time.

Most app developers pay no more than this initial fee, or the somewhat higher fee for enterprise developers. As Judge Yvonne Gonzalez Rogers wrote in her September 2021 decision in the court case involving Apple and game developer Epic: “over 80% of all consumer accounts [in the Apple App store] generate virtually no revenue as 80% of all apps on the App Store are free.” These are apps which are free to download, and have no in-app purchases or subscriptions. Many of them, like banking or airline apps, may be quite frequently downloaded and used. This huge swath of the app stores is disinflationary, with a price that is fixed in dollars over time.

Then there are the small percentage of apps which collect significant consumer revenues on the app stores. Most of these are gaming apps. For the purposes of assessing their impact on inflation, there are two important factors. One factor is whether the price of the subscription or in-app purchase is rising. The other factor is whether the percentage fee charged by Apple and Google for use of their platform is rising or falling.

We have little visibility into the price evolution of subscription costs and IAP prices. One survey from Sensor Tower suggest that the median price of subscriptions for non-game apps did not change from 2017 to 2020, while the median price of in-app purchases for non-game apps rose by 50%. However, even in the latter case, we have no way of knowing whether consumers are buying the same digital goods or shifting to higher value purchases, which matters for inflation.

We have much better information on the effect on inflation of the fees charged by Apple and Google. The statistical literature makes it clear that if the fee percentages stay the same, they has a neutral impact on inflation. If the fee percentages rise, that is inflationary. If fee percentages fall, that is disinflationary.

In the past year or so, both Google and Apple have voluntarily cut fees for a significant portion of their developer base. Apple, for example, cut the App Store fee from 30% to 15% for all developers who earned less than $1,000,000 in 2019. By one estimate, that covered 98% of apps with revenue in 2019. Google reduced its fee on subscriptions to 15% (previously it had charged 30% for the first year). These are substantial changes.

With the app store registration or membership fee being held constant in money terms, and revenue-based fee percentages falling, it’s clear that the app stores are contributing to disinflationary pressures.

Conclusion

Both historically and currently, the broad swath of tech, telecom, and ecommerce companies appear to be leaders in the fight against inflation. Data from the government and elsewhere shows no evidence of accelerating price increases in this sector.