The Covid-19 crisis has put a spotlight on how archaic government systems are failing to keep up with the times and handle an unexpected surge of applications for public assistance programs. Cybersecurity threats have demonstrated vulnerability in aging government IT systems. New missions and requirements for government technology capability have shown the limitations of 20th century technology systems and resources for addressing 21st century needs.

The scale of the problem is massive. According to our estimates, federal, state and local governments would have needed to spend an accumulated $316 billion more over the past 20 years to have kept up with the growth of software investment per worker in the private sector. This should be viewed as a lower bound on the shortfall in government IT investment, as this figure excludes hardware investments that also should have been made.

Washington needs to build incentives inside government for a technology culture of continuous improvement and innovation to keep up with external technology developments and changes. Absent such a major modernization strategy, government will become less and less functional in our everyday lives. We need a big push to modernize government, using new digital tools not only to deliver services more efficiently, but to reengineer public services to make them more citizen-friendly and empowering.

To meet public expectations for the kind of speed, versatility, accuracy and efficiency that Americans experience in the non-governmental aspects of modern daily life, we must once again reinvent government just as we did 25 years ago at the beginning of the internet age.

Congress has tried to provide critical relief to Americans during the Covid-19 pandemic — passing three phases of disaster relief totaling 13.6 percent of GDP — but the rollout of support has been marred by obsolete IT and bureaucratic culture.1 In June, the House Ways and Means Committee estimated between 30 to 35 million stimulus checks had yet to be issued.2

The initial rounds of the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) also were plagued by institutional delays, internal IT system crashes and incomplete, inaccurate and lagging databases. An April 2020 survey by the National Federation of Independent Business found that 28 percent of small business owners were unsuccessful in submitting an application for funds.3 The Small Business Administration’s loan processing system, known as E-Tran, crashed twice in April, frustrating lenders and small business owners seeking relief.4 5

State governments have also stumbled. For example, unemployment offices have been stretched thin as roughly 58 million Americans have filed claims since March.6 In Washington State, only 41 percent of claims had been paid as of July 30.7 Florida’s unemployment website has crashed repeatedly, with phone calls to the office going unanswered8, and citizens complaining of lengthy delays. Frustrated workers in Oklahoma and Kentucky have camped out overnight in front of unemployment offices for answers.9

The COVID-19 crisis is just the latest example of a chronic issue plaguing government programs at the state and federal levels. Poor information technology infrastructure and practices, antiquated and siloed systems, and outdated databases, have led to three main issues: security vulnerabilities, poor user experience and lengthy delays for citizens interacting with their government.

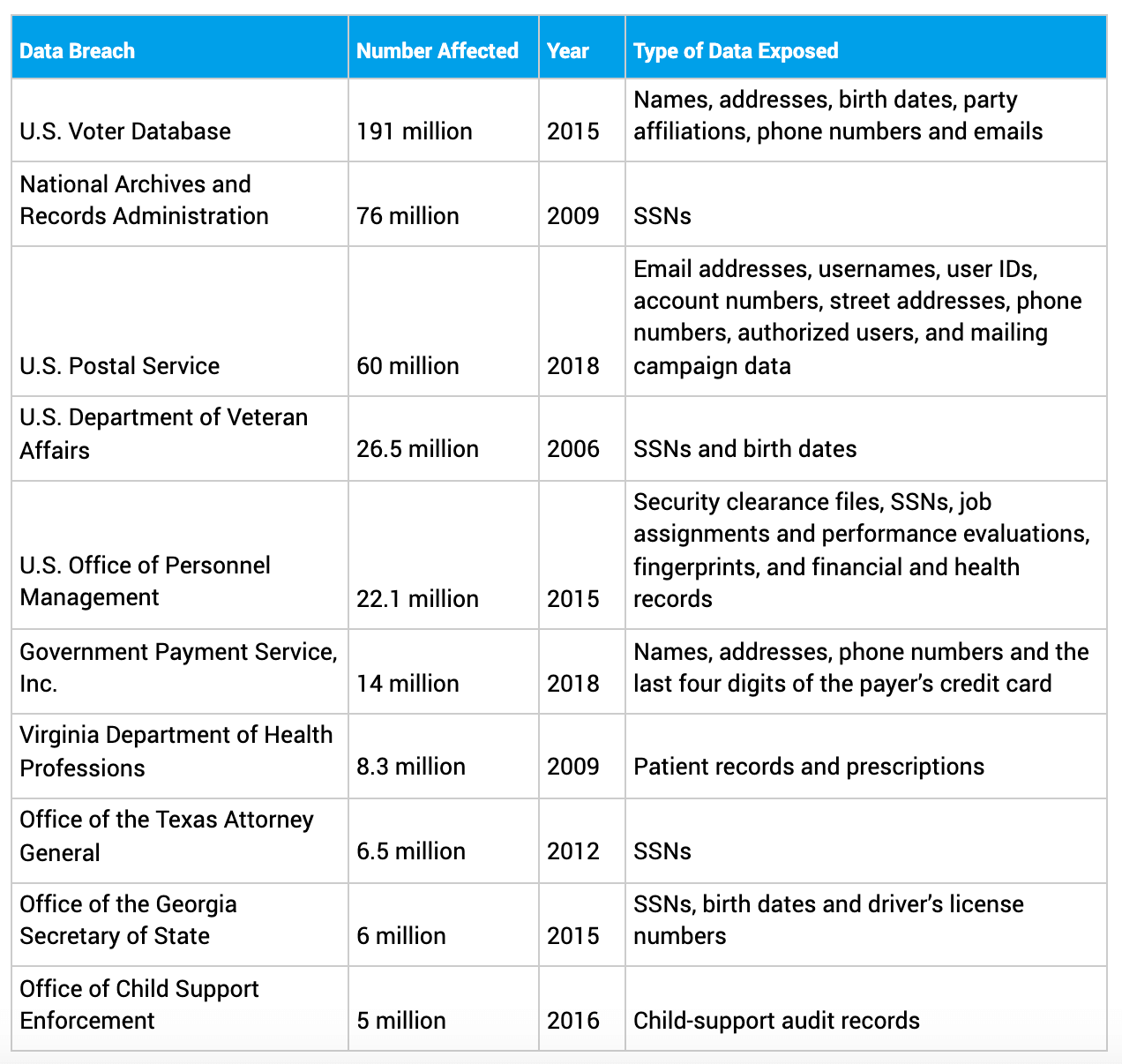

On the question of data security, perhaps the most infamous case is the data breach of the U.S. Office of Personnel and Management (OPM) in 2015 by hackers working for the Chinese military.10 The incident affected 22.1 million Americans and included data on security clearance files, Social Security numbers (SSNs), job assignments, performance evaluations, fingerprints, and financial and health records.

Most disturbingly, data missing from the OPM database could potentially be used by foreign spy services to uncover CIA operatives working under diplomatic cover, as Ellen Nakashima reported for The Washington Post: “Names that appear on rosters of U.S. embassies but are missing from the OPM records might, through a process of elimination, reveal the identities of CIA operatives serving under diplomatic cover.”11

But while the OPM hack may have attracted the most attention in recent years, it wasn’t even the largest hack of U.S. government data in terms of the number of people affected. As shown in the table below, data breaches of the U.S. Voter Database, the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), and the U.S. Postal Service (USPS) each affected more than 50 million Americans.

15

In addition to data breaches, government databases are often inaccurate and out of date, leading to ineffective performance. For example, the IRS taxpayer database contains incomplete and aging data, which resulted in improper payments in PPP benefits to large numbers of dead taxpayers, returned payments that were misdirected, and even funds sent abroad to foreign citizens of other countries. 12 13

Currently, the U.S. government spends the vast majority of its IT budget on maintaining and operating older legacy systems rather than upgrading and modernizing them. A 2019 Government Accountability Office report found that 80 percent of the $90 billion the federal government planned to spend on IT in 2019 would be used to operate and maintain existing systems.14 As shown in the table below, the report concludes that there are 10 legacy systems most in need of modernization, a few of which are more than 45 years old. One system at the Department of Education still runs on Common Business Oriented Language (COBOL), a programming language first introduced in 1959.

COBOL was originally designed for mainframe computers. While it has mostly died out in the private sector as businesses have transitioned from owning on-premise mainframe computers to renting cloud computing services from Amazon, Microsoft, or Google, COBOL has been in the news recently as government relief programs struggle to cope with surging demand.16

Government systems still rely on this outdated technology for essential services. At the state level, COBOL has been used to keep unemployment insurance programs running continuously for 40 years (34 state unemployment systems still depend on it today). 17 18 And during the current crisis, New Jersey’s governor put out a call for volunteers fluent in COBOL to help fix the state’s computer systems.19 Data from Indeed, a job listings search engine, showed a massive increase in search interest for “COBOL” in April.20 But there is a real risk these calls for help will go unanswered. COBOL is only the 43rd most popular programming language as of this year and the average age of a COBOL programmer is about 55-years-old.21 22

Why haven’t millions of people received their economic impact payments from the IRS yet? COBOL seems to be the culprit there, too. Many Americans encountered error messages (“Payment Status Not Available”) when they tried to find out why they hadn’t received their stimulus check yet.23 The solution? Using only uppercase letters in the form (and if that didn’t solve the issue, people were advised to try abbreviating words like “Street” and “Avenue”).

But the problems are not just limited to outdated programming languages. The IRS has a profoundly outdated and inaccurate taxpayer database and its systems are unable to talk to each other. John Koskinen, the Commissioner of the IRS from 2013 to 2017, testified on multiple occasions in Congress, and made other public statements, about the dangerously outmoded condition of the agency’s IT infrastructure, even citing existing systems that date back to the Kennedy Administration.24

Other government processes are also antiquated. In New York, newly unemployed workers are required to fax in documentation.25 In some states, people can file for unemployment online, but only from a desktop or laptop computer.26 The state websites, it turns out, aren’t mobile-friendly — a significant barrier for the millions of people whose only internet access is via their smartphones.27 And some states, such as Illinois, even shut down their websites for multiple hours every day.28

These problems with the government’s digital infrastructure didn’t arise overnight. Technical failures of this nature are the inevitable result of an accumulating investment deficit over recent decades. According to a Progressive Policy Institute analysis of Bureau of Economic Analysis data, federal and state government investment in software per worker significantly lags behind private sector investment. 29 30

As the pandemic recession grinds on, the federal and state governments must invest more in digitizing their operations if they are going to deliver aid faster and more accurately. U.S. officials should study the example of Estonia, which has digitized 99 percent of government services, including online voting, an e-residency platform that allows businesses across the European Union to establish and manage a business online, and a nationwide system of digitally-kept health records. 31 32 33 34 Estonian officials estimate that digitizing these processes saves the country two percent of its Gross Domestic Product a year in salaries and expenses, roughly what it pays to meet its military obligations to NATO.35

The federal government has a Technology Modernization Fund, but it’s only been allocated $125 million since 2017 when it was created. 36 37 In its big relief bills (such as the Paycheck Protection Program and the CARES Act), Congress included funds for agencies to upgrade their technology systems. For example, the bills allocated nearly $3 billion to the Small Business Administration that could be used to upgrade and modernize its IT systems. But much of the money has gone to hire outside contractors rather than to acquire new technology. For instance, the Small Business Administration awarded RER Solutions $500 million for data analysis and loan recommendations as part of Covid-19 relief. 38 Sufficient in-house technology systems would both limit the potential for breaches to occur and be a more prudent use of taxpayer money rather than continuously “renting” delivery systems.

For too long, the U.S. public sector has been a laggard in adopting the modern digital technologies that the rest of society have. That’s mainly been the result of underinvestment. To close this public-private technology gap, the federal and state governments need to invest more in software and systems improvements to ensure aid is rapidly delivered during the next crisis.

All of these issues might make it seem like the best approach is to tear everything out root-and-branch and start over. And while end-to-end modernization strategies might make sense in some cases, for the most essential government systems, an incremental strategy is actually best because it minimizes risks to essential services and limits downtime for users. As Alasdair Allan, a computer scientist at the Raspberry Pi Foundation, pointed out, legacy software systems have accumulated decades of solutions to corner cases and bug fixes. Starting from scratch would be a mistake:39

You should (almost) never rewrite from scratch, and (almost) never throw the legacy system away, it is your institutional knowledge. A legacy software system is years of undocumented corner cases, bug fixes, codified procedures, all wrapped inside software.

If you start from scratch you will miss things. There is no guarantee that you will end up in a better situation, just a different one. I have yet to speak to anyone that has been involved with a project to reimplement a large legacy code base from scratch that has anything good to say about the idea. Document, improve the build system, modernise the infrastructure around it. Write tests. But do not throw it away.

Modern programming languages can be used to deliver social services on modern devices (e.g., smartphones) while sitting on top of the existing mainframe servers. This approach would drastically improve the user experience while preserving the accumulated knowledge. But what might this look like in practice and where should the government start?

One area the federal government can look to improve incrementally in terms of delivery via information technology is anti-poverty programs. Low-income families spend inordinate amounts of time and energy running from one social service agency to the next to apply for public assistance. Now, with many offices shut down, social distancing, and intermittent mass transit, that job is harder than ever. The opportunity costs of simply applying for and receiving public support have risen dramatically. We need to use new digital tools to reduce those costs by empowering low income people to apply once online and receive benefits on an ongoing basis.

Over time, government IT systems have accrued a lot of technical debt — the cost of future work caused by choosing an easy, short-term fix.40 Solving these problems won’t be easy. But a step in the right direction would be passing the Health, Opportunity, and Personal Empowerment (HOPE) Act.41

As Joel Berg detailed in a white paper for PPI in 2016, the HOPE Act would jumpstart the modernization of social services with pilot projects and innovation contracts.42

“Currently, low-income families need to navigate a morass of bureaucracy to receive the benefits they need and deserve, including SNAP, WIC, and UI benefits. Filling out the requisite forms often requires waiting in long lines and traveling to far flung offices. For example, for residents of Panola, Alabama, the closest location to get a driver’s license is a 70-minute drive away.For more complicated processes, recipients often need to hire professionals to help them secure financial assistance from the government.

A 2016 PPI study found that low-income workers paid an average of about $400 each to national tax preparation storefront chains in low income neighborhoods.43 A better alternative would be to move all these services online and make them accessible from a single smartphone app.”

Nevertheless, the government — at both the federal and state and local levels — does not have a good track record of building large scale transactional systems. Moreover, poor customer experiences have too often resulted from government attempts to mimic the online transactional processes and consumer interfaces the public has come to expect from their daily experiences with private sector innovations. And as we’ve shown, the government has a big task ahead in fixing its current systems, in terms of financial resources, managerial resources, and tech talent resources.

However, the needs of the country also cannot wait for notoriously lengthy public procurement cycles to solve these problems. Just getting through the phases of systems design, specifications, and competitive procurement for major systems would take 5-10 years, while implementation of awarded contacts would take 5-10 years more, with high risk of obsolescence by the time of deployment. Successful government reinvention will therefore require reinvention of processes and strategies for service delivery in order to rapidly meet public expectations for performance. Innovative public-private partnerships, with appropriate public safeguards, should be a cornerstone methodology for government reinvention in the 21st century.

With all of that in mind, new online service delivery platforms could be provided via multi-sourced public-private partnerships – including those at no cost to either the public treasury or individual users — which would allow the government to harness the private sector’s technology capabilities and IT infrastructure, with a declared objective of creating an environment of continuous innovation and improvement. The government could then create supporting national public communications campaigns, down to the community level, to inform the public about the availability of these service platforms, so the working poor can know there is are free online, government-sponsored and regulated alternatives available to them.

According to Berg, the HOPE Act can help make this better alternative a reality:44

“Here’s how HOPE would work: The President and Congress would need to work together to enact a law that would authorize the federal Departments of Health and Human Services (HHS), Housing and Urban Development, (HUD), Treasury, and Agriculture (USDA) to work together – and to form public/private partnerships with banks, credit unions, and technology companies – to create HOPE accounts and action plans that combine improved technology, streamlined case management, and coordinated access to multiple federal, state, city, and nonprofit programs that already exist. States and localities would initially be asked to participate in pilot projects implementing the accounts and plans, and, if they work, would be required over time to implement them universally.”

The program would only cost $35 million in its initial stages and would go a long way to showing the potential benefits of bringing government tech into the 21st century. As Berg says, “In America, trying to get out of poverty can be a full-time job.”45 In normal times, this is a tragedy. In a pandemic, when tens of millions are at risk of becoming impoverished for the first time in their lives, this is a national emergency.

The HOPE Act can serve as the first step in a radically pragmatic approach to modernizing government IT. Senator Kirsten Gillibrand and Representative Joe Morelle have been leading the effort to include this bill in the Phase 4 relief package for the COVID crisis and low-income Americans need this change now more than ever.46

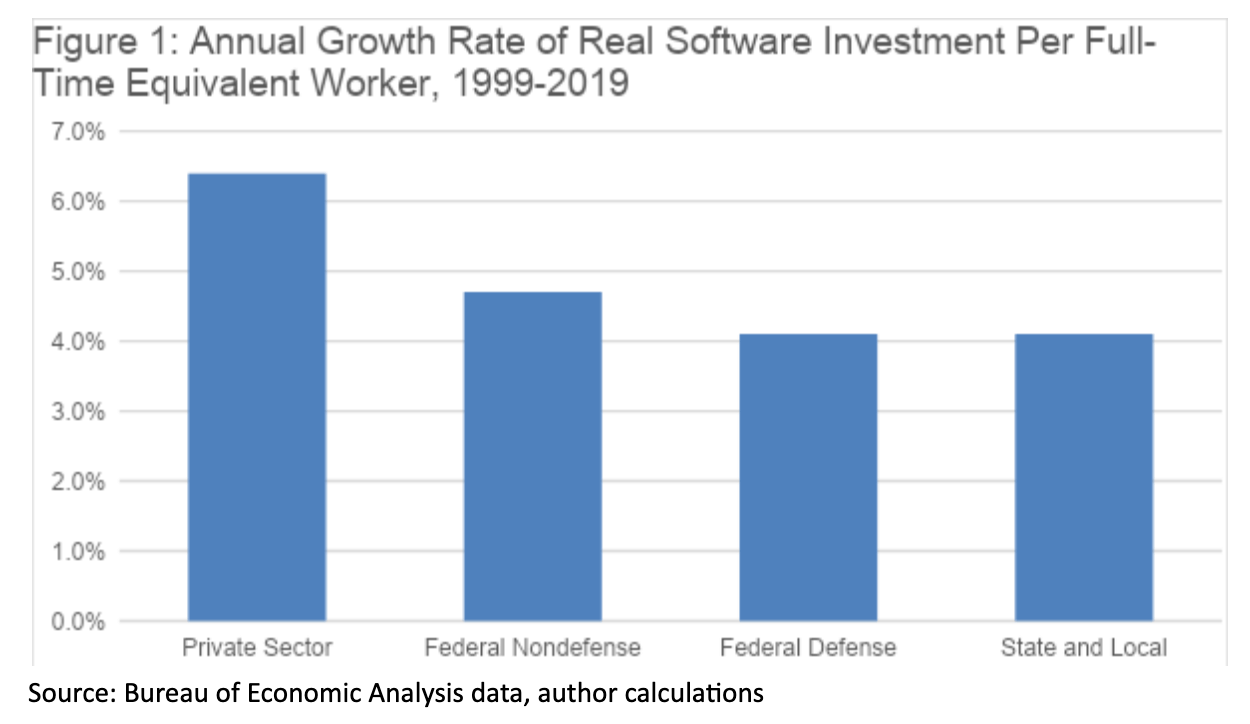

A big part of the problem is that government investment in software has not kept pace with the private sector. As Figure 1 shows, real private sector investment in software per full-time equivalent (FTE) worker increased at an annual growth rate of 6.4 percent over the last 20 years. Meanwhile real investment in software per FTE worker grew at a noticeably slower rate of 4.7 percent for federal nondefense, 4.1 percent for federal defense, and 4.1 percent for state and local governments.

If the federal nondefense sector had kept pace with the private sector, software investment in 2019 would be 38 percent, or $10.7 billion higher (Table 2). Software investment in the federal defense sector would be 55 percent higher, and state and local government software investment would be 54 percent higher.

Table 2: The 2019 Software Gap (billions) |

||||

| Actual software investment | Necessary software investment* | Size of the gap | ||

| Federal Nondefense | 28.3 | 39.0 | 38% | |

| Federal Defense | 12.6 | 19.5 | 55% | |

| State and Local | 20.1 | 31.0 | 54% | |

| *assuming that real software investment per FTE had kept up with private sector | ||||

| Data: BEA, PPI | ||||

But that’s not the worst of it. This gap has accumulated over time, as year after year the government has spent less than it should have. According to our estimates, the accumulated shortfall in government software investment since 1999 has totaled $316 billion. As Table 3 shows, federal nondefense, federal defense and state and local governments would have invested an additional $123.6 billion, $89.5 billion, and $102.5 billion, respectively, to match the private sector’s pace over the last 20 years. This should be viewed as a lower bound on the shortfall in government IT investment, as this figure excludes hardware investments that will also need to be made.

Table 3: Accumulated Shortfall in Software Investment, 1999-2019 (Billions) |

|||

| Federal Nondefense | $123.6 | ||

| Federal Defense | $89.5 | ||

| State and Local | $102.5 | ||

| Total | $315.6 | ||

| Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis data, author calculations | |||

| *See Methodology Appendix | |||

While the task of modernizing government technological capabilities may seem immense, it pales in comparison to the opportunity cost of not acting at all. A Technology CEO Council report highlighting opportunities for innovation in government use of technology estimated the federal government alone could save $1.1 trillion over the next decade in areas like fraud and improper payments prevention, big data and analytics, mobile, and cybersecurity.47 For example, the federal government is forecast to make $117 billion in improper payments in FY 2020 and has made over $1 trillion in improper payments since FY 2012.48 Technology CEO Council estimates “the federal government could reduce improper payments by approximately $270 billion over 10 years” by employing techniques like when IBM implemented predictive analytics for New York State, which resulted in the prevention of $1.2 billion in improper tax refunds.49

Cybersecurity is another area where modern technology can save taxpayer money. A study by the Ponemon Institute found the United States to have the highest average cost for a data breach in 2020 at $8.64 million.50 Public-private partnerships can help federal, state and local governments avoid expensive cybersecurity attacks. IT security company Akamai helped the U.S. State Department move to a secure cloud-based web presence that successfully protected the agency from one of the largest Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) attacks on U.S. government websites to date. 51

Once again, public-private-partnership is an essential part of a 21st century cyber defense strategy. A good example is the Treasury/IRS Security Summit and ISAC, which was created by IRS Commissioner Koskinen five years ago, in concert with the private sector. This Treasury/IRS initiative has thus far reduced identity theft tax refund fraud by 80.52 This innovative strategy to defend the tax system against international cyber-attacks should be studied as a model for other government agencies who hold sensitive information and billions in public assets.

The Covid-19 pandemic has shed a light on the obsolete systems used by federal, state and local governments to deliver relief. When time was of the essence, the federal government stumbled in delivering stimulus checks and PPP loans efficiently and accurately. State governments were ill-equipped to process the unprecedented surge in unemployment applications. To be sure, government IT issues predate the pandemic, as federal and state systems have been routinely compromised by data breaches.

The root cause of these IT problems is a decades-long shortfall in government infrastructure investment. For example, the overwhelming share of the federal government’s investment in IT is spent on operating and maintaining outdated legacy systems, some of which are more than half a century old. But the solution isn’t to maintain obsolete systems that aren’t secure and don’t serve their purpose anymore; the solution is for governments to invest in modernization and digitization. Governments should start with pilot projects and partner with the private sector where possible. The HOPE Act would represent a down payment on the $316 billion we estimate federal, state and local governments has fallen behind the private sector. Likewise, modern public-private partnership strategies would enable government to leverage private sector investments and infrastructure to apply them to public purpose.

Data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis enables us to calculate real software investment per full-time equivalent worker for the private sector, the federal nondefense sector, the federal defense sector, and the state and local sector. As shown in Figure 1, the growth rate was substantially faster in the private sector compared to the three government sectors.

We then calculated how much higher software investment in the three government sectors would have needed to be in each year since 1999 to match the growth rate of real software investment per FTE in the private sector. We then translated this increase into nominal dollars and summed over the twenty-year period to get the total shortfall. The 2019 figure gives the current gap reported in Table 2.

This estimate should be regarded as a rough measure of the amount of “software debt” that the government has built up. Ordinarily we might not worry about a lack of spending 10 or 15 years ago because of depreciation, but the government has spent far too much money holding legacy database systems together with scotch tape.

The other issue is hardware. The data published by the BEA for government spending on computers includes “consumption expenditures” as well as investment, so it doesn’t quite correspond with private sector investment in computers. It is generally agreed, however, that even in the era of cloud computing that the government needs to modernize its hardware.