Over the weekend, David Leonhardt published an op-ed in the New York Times entitled “The Democrats Are the Party of Fiscal Responsibility.” Leonhardt argues that Democrats get insufficient credit for the fact that federal budget deficits drop when their party holds the White House while deficits rise when Republicans take control. We believe Leonhardt is correct in his assessment of the partisan fiscal record, and it’s worth exploring why Democrats don’t get more credit for their accomplishments.

The most commonly used metric for evaluating a country’s fiscal situation is the budget deficit as a percent of gross domestic product, because the same budget deficit in dollars is less significant in the context of a larger national economy than it would be in a smaller one. The government is generally considered to be more fiscally responsible when it minimizes the deficit as a percent of GDP.

The exception to this rule is during an economic downturn. When the economy contracts, deficits can rise as a percent of GDP even if they remain at the same level in dollars. Additionally, temporary stimulus (in the form of either tax cuts or spending increases) is an important tool for combatting these economic downturns. Counter-cyclical deficits allow the government to pump money into the economy when it needs it the most, stimulating demand and reducing unemployment. Some programs, such as Unemployment Insurance, act as “automatic stabilizers” because they do this automatically during a recession without additional action by policymakers.

Leonhardt controls for these factors by comparing deficits as a percent of potential GDP (which is largely unaffected by swings in the business cycle) and by subtracting the impact of automatic stabilizers. In his analysis, Leonhardt found that deficits fell under every Democratic president since Jimmy Carter and rose under every elected Republican president since Ronald Reagan.

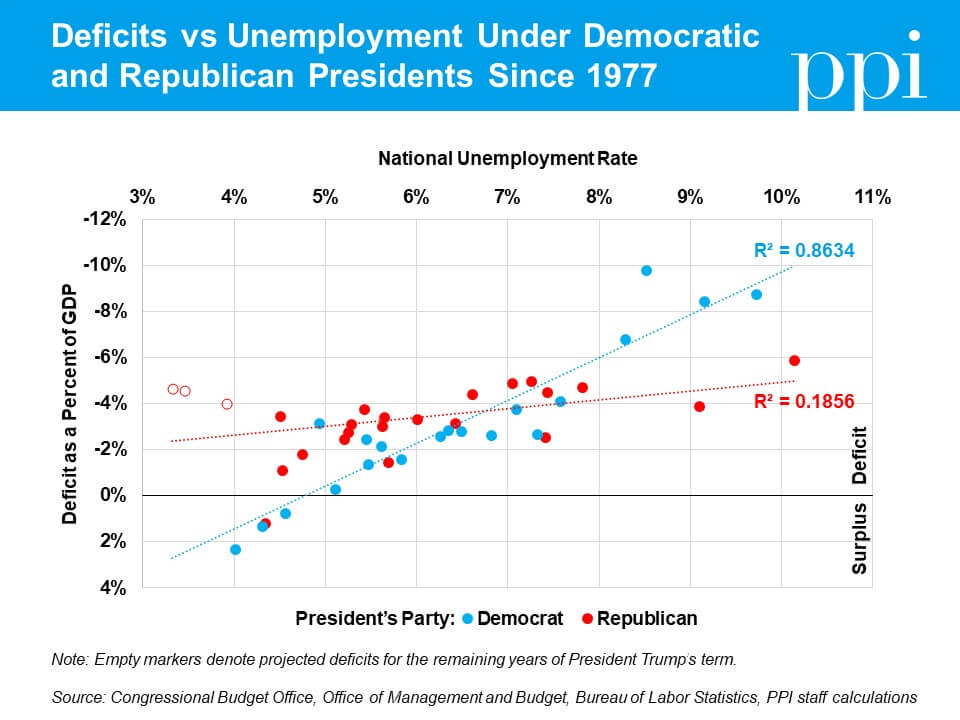

This measure, however, still penalizes presidents who choose to use additional stimulus beyond automatic stabilizers to bolster a flailing economy under their watch. An alternative way to analyze the data would be to compare deficits relative to unemployment under the presidents of each party. Below is a chart showing the correlation between deficits and unemployment under both Democratic and Republican presidents in every administration since Jimmy Carter:

Under Democratic presidents, the trend is essentially what one would expect to see from good counter-cyclical fiscal policy: When unemployment rises, so too do deficits. When unemployment falls, deficits fall as well (to the point where they actually became surpluses during the prosperous years at the end of the Clinton administration). This trend suggests a responsible stewardship of the federal budget under Democratic presidents.

The picture under Republican presidents, on the other hand, is very different. When a Republican occupies the White House, deficits have historically had little correlation to unemployment. The trend is continued by President Trump, who supported massive deficit-financed policies over the past year despite the fact that unemployment is just over four percent today. As a result, the non-partisan Congressional Budget Office now projects deficits over the remainder of Trump’s term that are significantly higher than those under any Democratic president presiding over an economy with less than seven percent unemployment.

If the fiscal record of Democratic presidents is so obviously superior to that of Republican presidents, why do Democrats not get credit for being the “party of fiscal responsibility”?

The first reason is that deficits reached their highest level in the modern era (9.8 percent of GDP) during the first year of the Obama administration. This unusually large deficit was a direct result of the 2008 financial crisis that President Obama inherited, and after excluding years in which average unemployment exceeded 8 percent, it becomes apparent that deficits under Democratic presidents have been consistently lower than deficits under Republicans facing comparable economic circumstances. Nevertheless, many voters still associate Democrats with the record-high deficits of the early Obama era.

Another reason Democrats don’t get more credit for declining deficits under their presidencies is that presidents simply do not deserve all the credit for deficit reduction that occurs on their watch. Both Presidents Clinton and Obama had to contend with at least one chamber of Congress being controlled by Republicans for six of their eight years in office. Congressional Republicans, despite being incredibly profligate under Republican presidents, have regularly demanded deep spending cuts when a Democrat occupies the oval office – spending cuts which contribute to declining deficits.

But the main reason Democrats don’t get credit for being “the party of fiscal responsibility” is that they often approach the subject with ambivalence. Many Democrats have been reluctant to criticize the GOP’s fiscal record either because they believe Republicans have demonstrated that deficits don’t matter politically or because they fear that admitting the importance of fiscal responsibility now will constrain their ability to deficit-finance progressive priorities in the future. Until Democrats resolve this ambivalence, voters won’t give the party credit for its responsible stewardship.

Donald Trump has handed Democrats a unique opportunity to correct course. With unified control of the federal government, Republicans have blown a massive hole in the federal budget. The nation may never again see an annual budget deficit below $1 trillion after 2020 if current policies remain in place. At a time when deficits are high and trust in government is low, Democrats need to demonstrate they have plan to pay for their policies if they expect voters to support further expansions of government. Now is the time to hold Republicans accountable for their reckless fiscal policy and offer the electorate a compelling alternative.

For more on this topic, please see our second blog that focuses on the fiscal record of each party in Congress.