While House Democrats and Senate Republicans remain at an impasse over how generous unemployment benefits should be in the current recession, a potentially greater problem is looming: millions of unemployed Americans will see their benefits terminated prematurely unless Congress takes additional action in the next three months. What’s more, many workers are forced to clear bureaucratic hurdles to qualify for extended benefits Congress approved last spring to help them ride out the pandemic.

This piece explains why jobless Americans are entangled in red tape and on course to lose their benefits at the end of this year. Congress should fix these problems by tying the duration of unemployment benefits to actual economic conditions rather than arbitrary deadlines, streamlining the transition from regular benefits to extended pandemic benefits, and requiring the states to do a better job of informing workers about special pandemic extensions.

People who lose their jobs through no fault of their own can typically draw unemployment benefits for 26 weeks. When unemployment spikes, the Extended Benefits (EB) program automatically extends the duration of benefits, usually for 13–20 weeks. But to buy unemployed people more time to find work amid the pandemic recession, Congress created a new program that offered 13 additional weeks of benefits for job seekers to draw before EB, called Pandemic Emergency Unemployment Compensation (PEUC). (Since some states offer unemployment benefits for fewer than 26 weeks, Congress also let people who exhausted all available benefits in fewer than 39 weeks make up the difference through the new program otherwise meant for self-employed workers, Pandemic Unemployment Assistance.)

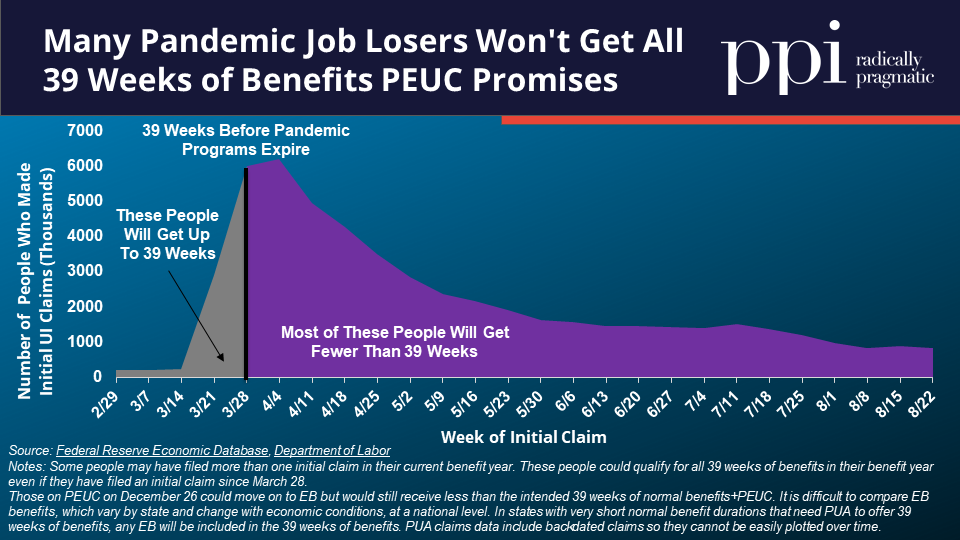

However, it turns out that many people who lost their jobs as a result of the pandemic will not receive all 39 weeks of unemployment benefits. Why? Because the pandemic-specific unemployment programs expire at the end of this year. That means that anyone who began receiving benefits after March 28 will have their pandemic benefits cut off before they receive 39 weeks of benefits.

Leaders may have hoped back in March that the pandemic would subside and the unemployed would not need an extension after December. But we now know that’s not likely. Instead of “going away” as President Trump said that it would, the pandemic became worse than ever, which hurt the economy and caused even more layoffs. Over 80 percent of all initial normal unemployment claims filed during the pandemic were filed with fewer than 39 weeks to go before the end of the year. While some of those recipients are repeat claimers who might still get the full benefit, evidence from California suggests most were newly unemployed people who cannot. Republicans’ refusal to negotiate seriously with House Democrats now risks undermining the stimulus that Congress has already passed by prematurely kicking millions from pandemic unemployment programs.

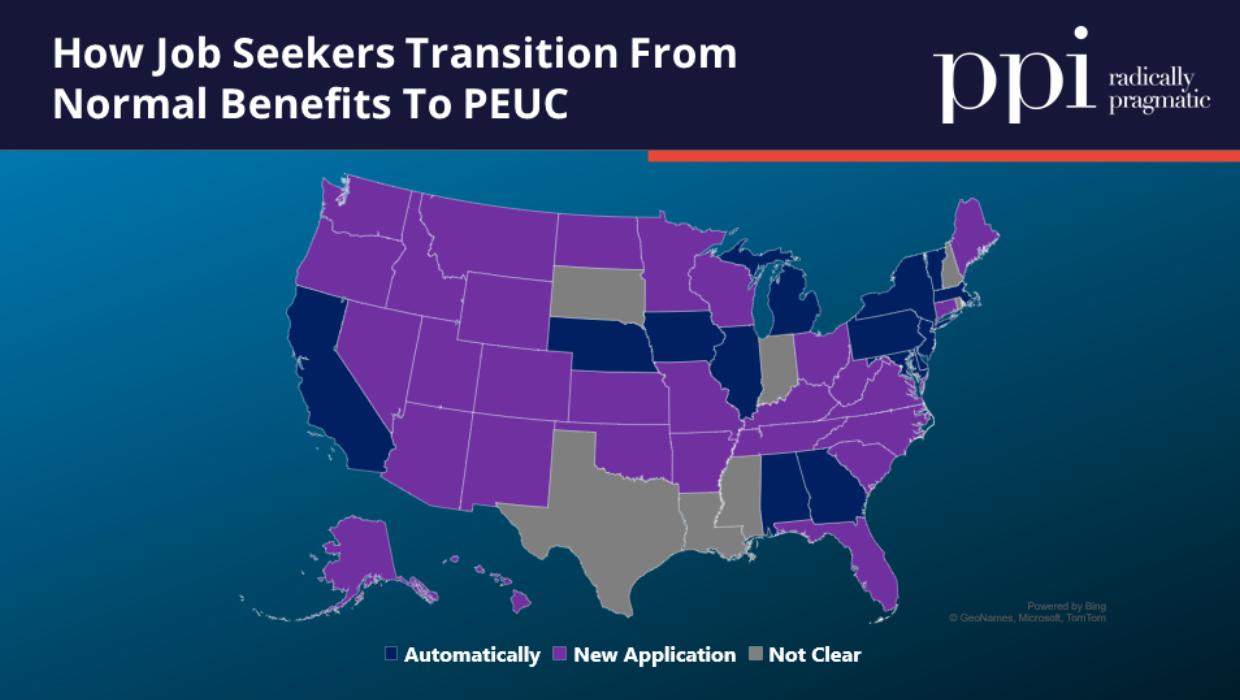

The looming cutoff isn’t the only problem facing unemployed people. To get however much of a benefit extension they do qualify for, recipients must also run a bureaucratic gauntlet through state unemployment offices already saddled with outdated technology and unprepared for the flood of applications. The U.S. Department of Labor has told states to require beneficiaries who have exhausted their normal benefits to actively apply for PEUC benefits, rather than receiving the benefits automatically. Some states are automatically enrolling beneficiaries in the program anyway, but PPI has only identified 14 such states, while 29 states indicate beneficiaries must specifically apply for PEUC in some way (several states have not yet set up their PEUC programs, and others do not indicate on their websites how beneficiaries transition from normal benefits to PEUC). This new application is simple in some jurisdictions, but onerous in others. Jobless people in Arkansas, for example, must physically go to a state unemployment office to apply for these benefits, even though they can apply for normal benefits online.

These extra barriers could deter some recipients from getting the benefits they are entitled to. And beneficiaries who may have already survived onerous wait times to get their normal benefits may once again face delaysas states struggle to process PEUC applications. Kansas warns people transitioning from normal unemployment benefits to PEUC to expect delays in their payment, which can be brutal on cash-constrained people struggling to pay their bills.

Federal policy requires states to notify people who are likely eligible for PEUC, but many are not doing so until after a recipient exhausts their normal benefits, which risks leaving people confused as to whether they are entitled to more benefits. Although I have found no good data on how common this is, anecdotal evidence from my experience suggests the problem is real. My mother, who is furloughed, did not understand what the benefit extensions would entitle her to, and those extensions made gave her a better alternative to accepting an early retirement offer from her employer. Another close friend, who is unemployed, was planning to move to his parents’ house hundreds of miles away before he found out about PEUC through his own research. States should inform all recipients of everything they are entitled to when they begin receiving benefits (or as soon as new information becomes available) so no one makes life-changing decisions based on incomplete information.

Spending more on unemployment benefits helps more than just the recipients themselves — it helps the economy in which that money is spent. And while Congress can and should do both, extending the duration of unemployment benefits might do even more to stimulate the economy than increasing the size of benefits. This is because money put into circulation by the government only stimulates the economy if it gets spent on goods and services by those who receive it. Beneficiaries are likely to spend every dollar of a small benefit to pay for necessities, but every additional dollar is slightly less essential to maintain their standard of living. As the size of the benefits grows, recipients are more likely to save rather than spend a greater share of those benefits. Accordingly, the jobless population is more likely to spend money they receive from a benefit extension than they are a bigger weekly benefit with a similar cost.

Further, the long-term unemployed are less likely to have savings or other resources to support themselves, making it even more likely they will spend a large share of their benefit. And contrary to GOP Senator Rand Paul’s claim that said “If you give people money and you make it less painful to be in a recession we can stay in a recession longer,” research on the Great Recession found that extending benefit duration did not create a strong disincentive to work. Because people can only draw unemployment benefits if they are looking for a job, extending unemployment benefits can give recipients a vital lifeline without holding back the economic recovery.

To strengthen this safeguard for job seekers and the economy, Congress should return to the negotiating table and take three immediate actions:

For more information on how states say people can apply for PEUC, see below.

State, How are Normal Beneficiaries Transferred to PEUC:

Alabama, Automatically

Alaska, New Application

Arizona, New Application

Arkansas, New Application

California, Automatically

Colorado, New Application

Connecticut, New Application

Delaware, Automatically

Florida, New Application

Georgia, Automatically

Hawaii, New Application

Idaho, New Application

Illinois, Automatically

Indiana, Not Clear

Iowa, Automatically

Kansas, New Application

Kentucky, New Application

Louisiana, Not Clear

Maine, New Application

Maryland, Automatically

Massachusetts, Automatically

Michigan, Automatically

Minnesota, New Application

Mississippi, Not Clear

Missouri, New Application

Montana, New Application

Nebraska, Automatically

Nevada, New Application

New Hampshire, Not Clear

New Jersey, Automatically

New Mexico, New Application

New York, Automatically

North Carolina, New Application

North Dakota, New Application

Ohio, New Application

Oklahoma, New Application

Oregon, New Application

Pennsylvania, Automatically

Rhode Island, Not Clear

South Carolina, New Application

South Dakota, Not Clear

Tennessee, New Application

Texas, Not Clear

Utah, New Application

Vermont, Automatically

Virginia, New Application

Washington, New Application

West Virginia, New Application

Wisconsin, New Application

Wyoming, New Application