This week’s episode is a joint episode of the Neoliberal Podcast and the PPI Podcast, featuring guest host Colin Mortimer of PPI’s Center for New Liberalism. Colin sits down with Oregon State Treasurer Tobias Read to talk about the ways Oregon is optimizing its treasury to support and empower Oregonians. Colin and Treasurer Read discuss the day-to-day role of a State Treasurer, and how his team uses the state’s investment power to help citizens, as well as how behavioral ‘nudge’ programs can increase retirement savings.

Category: Uncategorized

PODCAST: Joint Episode – Neoliberal Podcast ft. Oregon State Treasurer Tobias Read

This week’s episode is a joint episode of the Neoliberal Podcast and the PPI Podcast, featuring guest host Colin Mortimer of PPI’s Center for New Liberalism. Colin sits down with Oregon State Treasurer Tobias Read to talk about the ways Oregon is optimizing its treasury to support and empower Oregonians. Colin and Treasurer Read discuss the day-to-day role of a State Treasurer, and how his team uses the state’s investment power to help citizens, as well as how behavioral ‘nudge’ programs can increase retirement savings.

Imposing Price Controls on Delivery Services Won’t Save the Restaurant Industry, a Bailout Will

Contact: Carter Christensen, media@ppionline.org

WASHINGTON, D.C. – A new report from the Progressive Policy Institute discusses the impact of state and local price controls on food delivery services and explores other policy solutions that would actually help small restaurant owners and their workers weather the recession caused by the COVID pandemic.

The industry has some big chains, but most restaurants are quintessentially small businesses. More than 9 in 10 restaurants have fewer than 50 employees. More than 7 in 10 restaurants are single-unit operations. Restaurants also offer lots of entry-level jobs for less-skilled workers (almost one-half of workers got their first job experience in a restaurant). Delivery services have been one of the few sectors expanding during the pandemic, providing work for those who need it and helping many Americans stay safe during the pandemic. With the goal of helping restaurants, some states and cities have temporarily capped the commissions these platforms can charge restaurants for delivery. These price controls are popular with elected officials because they look like a cost-free way to help struggling restaurants, but their costs are hidden, not free, and will hit small restaurants and their workers hardest.

While bailouts are never uncontroversial, bailing out the restaurant industry is an easy call. There is no moral hazard risk as there was with the bank bailouts in 2008, when it was reasonable to worry that bailed out financial firms would increase their risky behavior in the future knowing that they would be bailed out in the event of a crisis. In this case, restaurants won’t change their behavior in the future in a way that increases the odds of a deadly pandemic.

Read the full paper here.

Electric cars are the future. Here’s how to get American drivers interested in them.

Major electric vehicle announcements by President Joe Biden and General Motors are being hailed as a turning point in the transition to widespread EV production and deployment in America. This matters greatly, because this crucial technology can both jump-start U.S. manufacturing to ease the economic and jobs crisis, and rapidly reduce emissions that cause climate change.

But there are still serious barriers to EVs. By far the biggest is the lack of American consumer demand for electric vehicles.

EVs, including plug-in electric hybrids, accounted for less than 2% of new U.S. vehicles sold in 2019.

This number is far lower than in other major markets, especially China, which has triple U.S. production and deployment volume.

Just as worrisome, only 14% of Americans say they are considering buying an EV, compared with 73% of Chinese motorists.

Read the full piece here.

Price Controls Won’t Fix What’s Ailing the Restaurant Industry

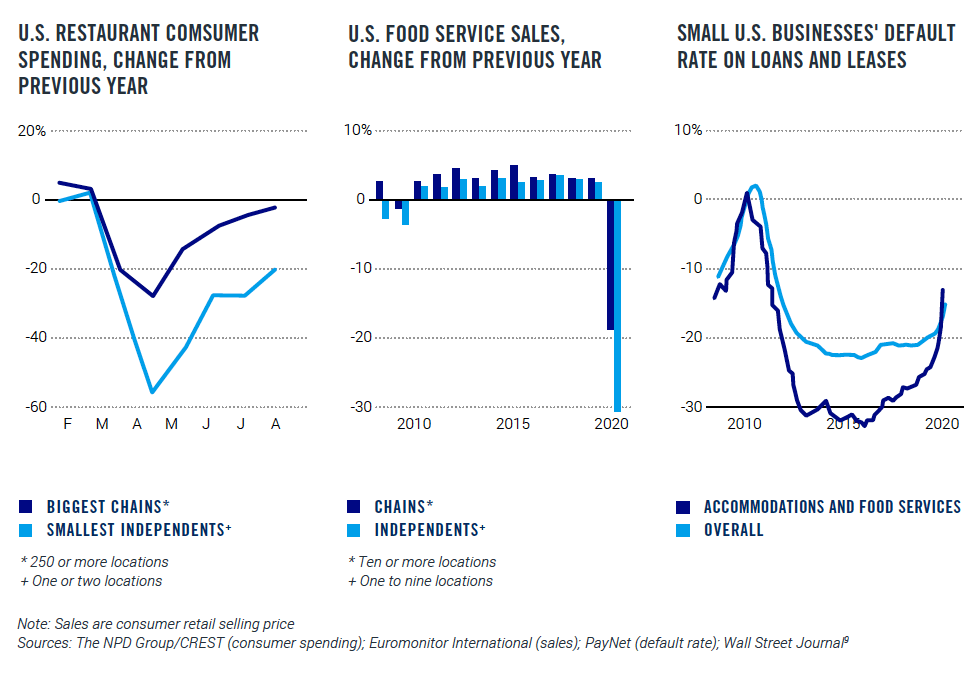

The restaurant industry is hurting. Between February and April of last year, more than 6 million food service workers lost their jobs.1 As of December, more than 110,000 restaurants had closed permanently or long-term.2

The industry has some big chains, but most restaurants are quintessentially small businesses. More than 9 in 10 restaurants have fewer than 50 employees. More than 7 in 10 restaurants are single-unit operations.3 Restaurants also offer lots of entry-level jobs for less-skilled workers (almost one-half of workers got their first job experience in a restaurant).

There is almost no safe way to allow indoor dining during an outbreak of a lethal, airborne, and highly contagious virus. Customers must remove their masks to eat and restaurant dining is traditionally done indoors with tightly packed groups of people. Some restaurants have chosen to remain open by relying on pickup and delivery orders instead of indoor dining, and for certain kinds of food, like pizza, this is a natural extension of their previous business model. For others, it’s a difficult transition to figure out pricing and what types of food work for takeaway. Many restaurants rely on third-party services for aggregating online orders and for fulfilling the delivery to customers.

Delivery services have been one of the few sectors expanding during the pandemic, providing work for those who need it and helping many Americans stay safe during the pandemic. With the goal of helping restaurants, some states and cities have temporarily capped the commissions these platforms can charge restaurants for delivery. These price controls are popular with elected officials because they look like a cost-free way to help struggling restaurants, but their costs are hidden, not free, and will hit small restaurants and their workers hardest.

While well-intentioned, imposing price controls will slow the economic recovery in a sector that’s among the hardest hit by COVID. To understand why, it’s important to know how these platforms work. Food delivery services are multi-sided markets, meaning the platform owner is trying to connect multiple “sides” of the market in mutually beneficial exchange. In this case, the business is trying to connect three groups: drivers, restaurants, and consumers. The balance of fees, commissions, and prices on all three sides of this market is set to achieve a high volume of orders, meaning revenue for restaurants and earnings for delivery drivers. Price controls on one side of the market upset this delicate balance.

In general, most economists view price controls as an ineffective and inefficient means of achieving lower costs for underserved groups. In a classic example, rent control leads to underinvestment in construction and maintenance of housing. Landlords are incentivized to convert their apartments into condos or let friends and family live in the units. Under rent control, property owners often charge a large upfront payment to secure a lease. Economists are also skeptical of vaguely written price gouging laws or price controls on essential medical supplies during a public health emergency. A much better solution, many economists argue, is for the government to step in and pay the market rate (to encourage supply) and redistribute the goods based on need.

There is a narrow range of circumstances when price controls can be beneficial for social welfare. In static and monopolistic markets, price controls can make sense to prevent dominant incumbents from charging monopoly prices and harming consumers. A second exception to the rule is during a natural disaster or other emergency. If supply is extremely inelastic (meaning non-responsive to price changes) during a crisis, then price-gouging laws can be beneficial on net. But to be clear, these laws need to be precise and narrow in scope.

If the emergency lasts beyond a few days or weeks, then relaxing price controls might be necessary to encourage an increase in supply.

Neither of these exceptions applies to the food delivery market in this crisis. The market for food delivery services is highly competitive (aggregate profits in the industry are negative4) and the current public health emergency has already lasted for more than a year. Instead, we can expect price controls on food delivery to have the usual negative effect. And based on early data from the cities that have capped commissions, that’s exactly what’s happening.5 Companies are shifting the costs from restaurants to consumers in the form of higher fees, and because consumers are generally more sensitive to price increases, this is leading to a reduction in output in these markets.6 Fewer orders means less business for restaurants and less income for drivers.

There’s a better way forward. The federal government can provide (and has provided) direct bailouts of the businesses and their workers. Unemployed workers have received extended and bonus unemployment benefits. These benefits should be continued for the duration of the public health emergency. Restaurants should receive grants and loans so they can continue paying rent and other fixed costs while closed. These programs should be funded to the level that every restaurant can benefit from them. “Just give people and businesses cash” sounds simple (and expensive), but the alternatives are much worse. Providing no help to restaurants would force them to choose between closing permanently or staying open — thus exacerbating and prolonging the pandemic. Imposing price controls will likely lead to a reduction in output, harming consumers, drivers, and restaurants in the process. The answer is for the federal government to help bridge the gap to the end of the pandemic by continuing and increasing its support for workers and businesses.

INTRODUCTION: RESTAURANTS NEED HELP

The restaurant industry has been hit especially hard by the pandemic. COVID-19 is an airborne respiratory illness that spreads most easily when people are (1) indoors (2) unmasked (3) and close together for an extended period of time. Unfortunately, that description matches restaurants perfectly, which is why many states forced them to close indoor dining during various stages of the pandemic. It’s not the fault of restaurant owners or workers that they were unable to stay open, so policymakers have a duty to make them whole.

More than one in six restaurants have been forced to close permanently — about 110,000 establishments — according to data from the National Restaurant Association.7 Small local restaurants are doing much worse than large chains, which have the advantages of “more capital, more leverage on lease terms, more physical space, more geographic flexibility and prior expertise with drive-throughs, carryout and delivery,” according to the Wall Street Journal.8

Understandably, federal, state, and local governments are trying to support the restaurant industry during this difficult time. The federal government supported restaurant workers with extended and bonus unemployment benefits and it supported businesses through the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) with $350 billion in April 2020 and $284 billion in December 2020.11 Of course, state and local governments, most of which have balanced budget rules12 (and none of which can print its own currency), are unable to serve as lender or insurer of last resort. Good intentions — the desire to help local restaurants — have unfortunately led some states and cities to adopt a shortsighted and counterproductive policy response: price controls.

San Francisco was one of the first cities to institute a commission cap on meal delivery services, limiting the fees they can charge restaurants to 15 percent.13 Seattle, New York, Washington, D.C., and other cities soon followed suit. As expected, the food delivery apps raised consumer fees in response. DoorDash added a $1.50 “Chicago Fee” to each order after the City Council capped restaurant commissions at 15 percent.14 Uber Eats added a $3 “City of Portland Ordinance” surcharge after the city imposed a 10 percent commission cap.15 In Jersey City, in response to a 10 percent commission cap, Uber Eats added a $3 fee and reduced the delivery range for restaurants.16

To understand why these measures haven’t achieved their stated aims, and why they will likely continue to have unintended consequences, first we need to understand what price controls are and the limited contexts in which they are effective.

WHY PRICE CONTROLS ARE USUALLY BAD

A price control is a government mandate that firms in a given market cannot charge more than a specified maximum price for a good or service (e.g., rent control for apartments) or they cannot charge less than a specified minimum price for a good or service (e.g., minimum wage for labor). Governments usually implement price controls with a noble aim of reducing costs of essential goods (e.g., shelter, fuel, food, etc.) for low-income people or supporting the revenues of a favored industry (e.g., price supports for farmers).

Policymakers tend to justify the imposition of a price control by arguing that the unrestrained forces of supply and demand will not ensure an equitable distribution of resources in essential markets. For politicians seeking to retain their jobs, price controls have the added benefit of being “off-budget,” meaning elected leaders don’t need to raise taxes to pay for them. While the costs of price controls may be unseen from a budgetary perspective, they are certainly not zero. Consumers, workers, and businesses are harmed by the lost output due to shortages under a price ceiling and excessive output under a price floor.

As Fiona Scott Morton, a professor of economics at Yale University, wrote, “If government prevents firms from competing over price, firms will compete on whatever dimensions are open to them.”17 And there are a multitude of dimensions beyond price. In response to price controls during World War II, hamburger meat producers started adding more fat to their burgers. Candy bar companies made their packages smaller and used inferior ingredients. During WWI, consumers who wanted to buy wheat flour at official price often had to buy rye or potato flour too.18

Generally speaking, after rent control takes effect, landlords reduce their maintenance efforts on rent-controlled apartments.19 They also pull rental units from the market and either sell them as condos or let friends and family live in them. Landlords can also capture some of the original economic value of their rental units by adding a fixed upfront payment to rental agreements. When airfare prices were set by the Civil Aeronautics Board between 1938 and 1985, airlines competed on other non-price dimensions, including improving the meal quality and increasing the frequency of flights and the number of empty seats.

The stricter the price controls are, the more likely bribes and other black market activity will substitute for previous white market activity. Even worse, the black market has higher prices than the legal market because sellers need to be compensated for the risk of being caught and punished by the authorities. Queuing and rationing are also extremely common under price controls. Hugh Rockoff, a professor of economics at Rutgers University, explains how price controls on oil had this effect in the 1970s:

Because controls prevent the price system from rationing the available supply, some other mechanism must take its place. A queue, once a familiar sight in the controlled economies of Eastern Europe, is one possibility. When the United States set maximum prices for gasoline in 1973 and 1979, dealers sold gas on a first-come-first-served basis, and drivers had to wait in long lines to buy gasoline, receiving in the process a taste of life in the Soviet Union.20

Henry Bourne, an early twentieth century economist, perhaps summed it up best when describing price controls in France during the French Revolution:21

It was the honest merchant who became the victim of the law. His less scrupulous compeer refused to succumb. The butcher in weighing meats added more scraps than before…other shopkeepers sold second-rate goods at the maximum [price]… The common people complained that they were buying pear juice for wine, the oil of poppies for olive oil, ashes for pepper, and starch for sugar.

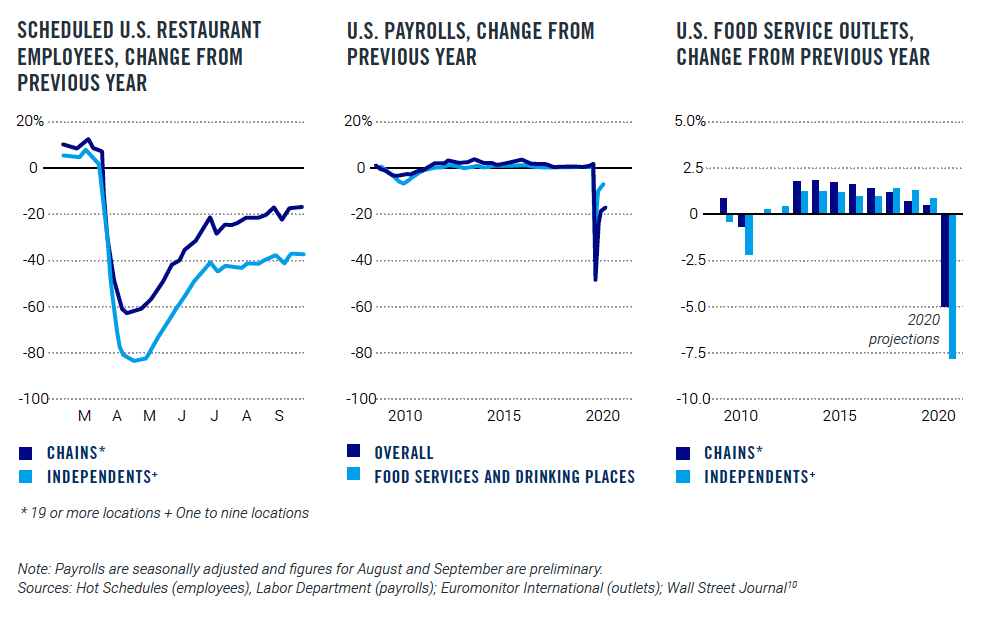

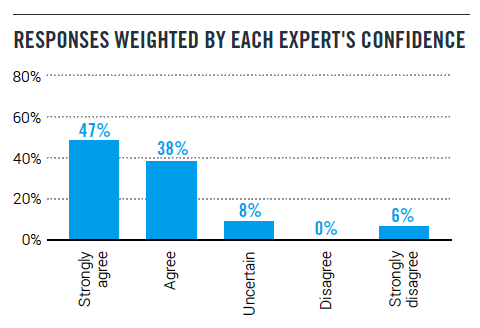

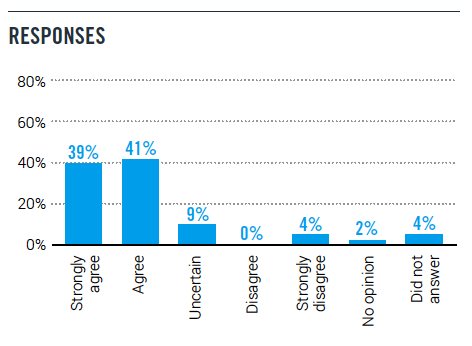

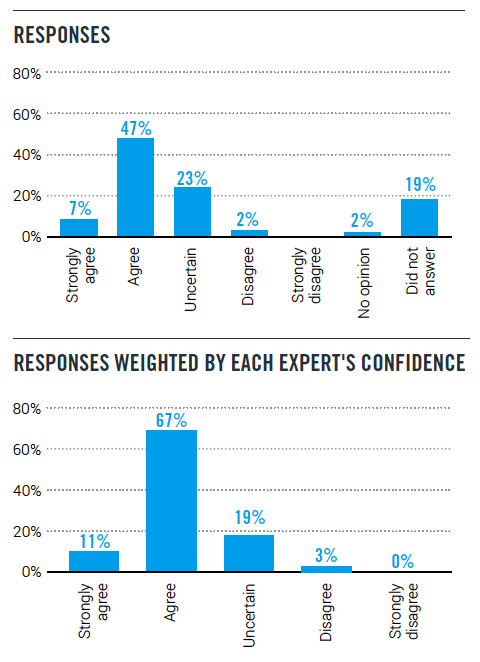

Indeed, price controls do not make competitive pressures magically go away; they merely get sublimated into other dimensions of competition — and those who abide by the spirit of the law are punished the most. The aforementioned problems are why economists dislike price controls and favor market-clearing price mechanisms. The Initiative on Global Markets (IGM) regularly surveys a group of leading economists on various questions of public interest. The questions related to different kinds of price controls have been quite lop-sided.

A 2012 survey about rent control asked the following question:22

Local ordinances that limit rent increases for some rental housing units, such as in New York and San Francisco, have had a positive impact over the past three decades on the amount and quality of broadly affordable rental housing in cities that have used them.

And here are the results:

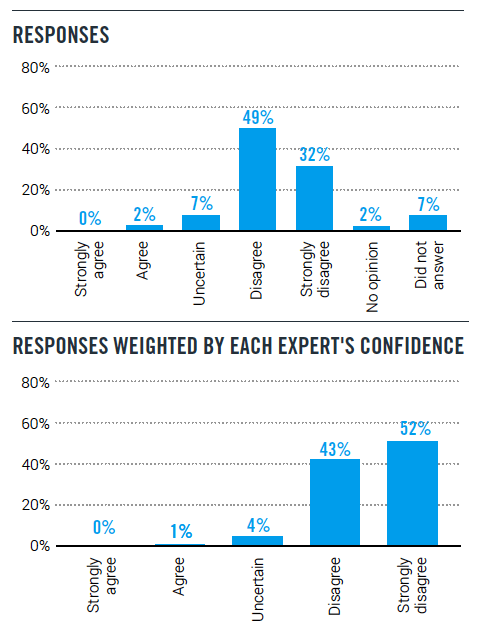

A 2014 survey asked about surge pricing:23

A 2020 survey points to an alternative mechanism for achieving the efficiency benefits of high prices without incurring the distribution costs:

Governments should buy essential medical supplies at what would have been the market price and redistribute according to need rather than ability to pay.

THE EXCEPTIONS WHEN PRICE CONTROLS ARE GOOD

There are two general exceptions when the benefits of price controls might outweigh the costs. First, in markets with natural monopolies and static competition, price controls can prevent dominant incumbents from harming consumers by charging monopoly prices (and restricting output). This is generally how utilities regulation works in the US. Electricity, natural gas, water, and sewage are examples of natural monopolies. It would be highly inefficient to lay two sets of water, gas, or sewage pipes to every house. Similarly, it wouldn’t make sense to have two electrical grids that connect to every house.

There are also low risks to investment efficiency by imposing price controls on these services. We have very likely reached the end of history in terms of innovation in water, sewage, and natural gas. Firms don’t need the incentive

of large monopoly profits to invest in water innovation because it’s just water. The optimal number of competitors in these markets is likely one. Utility regulators work closely with these companies to set prices that allow the firms to recover their fixed costs while earning a reasonable but not extortionate profit.

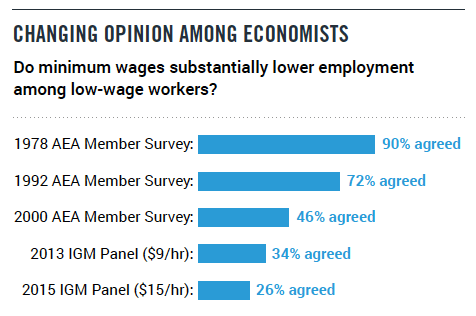

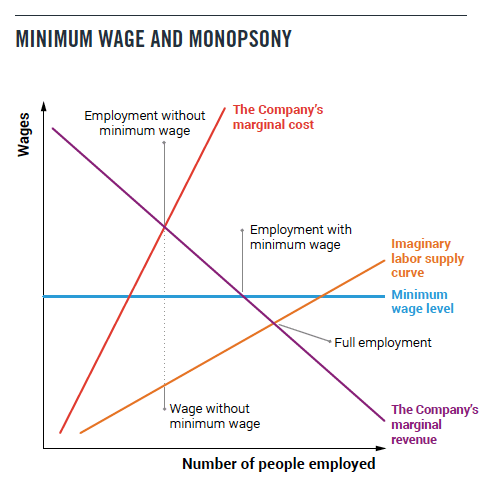

As Noah Smith, a columnist for Bloomberg, pointed out recently, economists have warmed to one other type of price control over the last few decades: the minimum wage.24

And this shift has occurred for the same reason economists are less worried about price controls in utilities markets: lack of competition. Empirical evidence has started to pile showing significant monopsony power in labor markets, particularly in rural areas.25 As this annotated chart from Noah Smith shows, when a firm has monopsony power in a local labor market, a minimum wage can actually increase employment.

This isn’t the case in all labor markets, of course. Urban markets have much more competition for low wage workers than rural markets. And economists are still worried that a national minimum wage of $15 per hour might lower employment in many states.26 But modest minimum wage increases are a price control that economists feel increasingly comfortable supporting.

The other axis to consider in addition to competition is time. Is the price control permanent or temporary? In the event of natural disasters and public emergencies, price controls (such as price gouging laws) can be reasonable. The normal reason policymakers should allow prices to spike in response to surging demand is to incentivize more supply to enter the market. But in a period of days or a couple of weeks during a disaster, supply may essentially be fixed (due to lack of outside access to the affected market). For very limited periods of time, caps on prices can ensure that a fixed quantity of supply is not allocated merely on willingness to pay (which is often a function of wealth as much as preferences).

PRICE CONTROLS AND MULTI-SIDED PLATFORMS

Before we examine how price controls are likely to affect the food delivery market, let’s first review the basic business models in question here, because they are distinct from traditional markets with only one type of customer. Food delivery apps are operating what are known as multi-sided platforms or markets.

What’s a multi-sided platform?

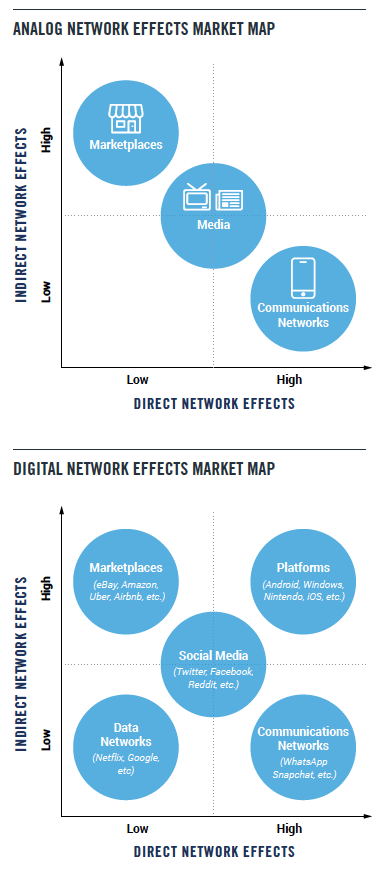

First it’s important to understand network effects. There are direct network effects and indirect network effects. Direct network eff

ects are when a product becomes more valuable to an individual user as more total users start using it. The telephone is the classic example. A telephone is only valuable insofar as it can be used to call other people who also own telephones. Indirect network effects are when consumers derive value from a distinct group of users on a platform. For example, consider shopping malls. The shopping mall owner needs to appeal to tenants to ensure the mall has lots of attractive stores for shoppers. But stores only want to sign lease agreements for space in shopping malls with lots of shoppers. The shopping mall owner is in a sense a matchmaker for these two groups. Newspapers and magazines are another example from the analog era. Advertisers want to advertise in publications with a lot of readers and readers want to read engaging content at a low cost. Publishers bring readers and advertisers together in a mutually beneficial exchange.

ects are when a product becomes more valuable to an individual user as more total users start using it. The telephone is the classic example. A telephone is only valuable insofar as it can be used to call other people who also own telephones. Indirect network effects are when consumers derive value from a distinct group of users on a platform. For example, consider shopping malls. The shopping mall owner needs to appeal to tenants to ensure the mall has lots of attractive stores for shoppers. But stores only want to sign lease agreements for space in shopping malls with lots of shoppers. The shopping mall owner is in a sense a matchmaker for these two groups. Newspapers and magazines are another example from the analog era. Advertisers want to advertise in publications with a lot of readers and readers want to read engaging content at a low cost. Publishers bring readers and advertisers together in a mutually beneficial exchange.

Digital markets often have these indirect network effects, too. For example, drivers want to drive on ride-hailing apps with lots of riders and riders want to ride on ride-hailing apps with lots of drivers. It’s Uber and Lyft’s job to set the price schedule (the commission it charges drivers, incentives it offers drivers and riders) at the optimal level. The same is true for operating systems. App developers want to develop apps for platforms with lots of users and users want to use platforms with lots of apps. Ditto for video game consoles: video game developers want to develop games for consoles with lots of gamers; gamers want to buy consoles with lots of games. The charts to the right show which products and services have direct network effects, indirect network effects, or both.

One of the most important questions for the owner of a multi-sided platform is how to set the prices on each side of the market. Economic research shows that the platform owner should charge lower prices to the side of the market that has relatively elastic demand (meaning consumers are sensitive to price changes and will change their quantity demanded sharply) and higher prices to the side of the market that has relatively inelastic demand.27 The most elastic side should pay the lowest price, and often it makes sense to charge them below-cost prices (“free shipping” or “free delivery”). That’s the “subsidy” side of the platform. The side with the lower elasticity of demand is the “money” side. Generally speaking, consumers have a higher elasticity of demand and suppliers (e.g., drivers, merchants, developers, hosts, etc.) have a lower elasticity of demand.

What are the likely effects of a price control on a multi-sided platform?

Research from Rob Seamans and Feng Zhu studied how Craigslist’s entry into various local markets affected the classified ads business of local publishers.28 Remember, newspapers are also operating multi-sided markets. They need to attract a large number of readers so they can then attract a large number of advertisers. Most classified ads on Craigslist are free, so its market entry represented a marked increase in competition on one side of the publisher’s market. For publishers, this leads to “a decrease of 20.7 percent in classified-ad rates, an increase of 3.3 percent in subscription prices, a decrease of 4.4 percent in circulation, an increase of 16.5 percent in differentiation, and a decrease of 3.1 percent in display-ad rates.” The authors go on to show that “these affected newspapers are less likely to make their content available online.” Changes on one side of a multi-sided market ripple throughout the other sides.

While the research literature on multi-sided platforms offers some insight about what might happen in the event of a price control on one side of food delivery platforms, we can also just look at real world evidence to see what’s happening. According to a recent article in Protocol:

On May 7, Jersey City capped delivery app fees charged to restaurants at 10%, instead of the typical 15% to 30% many such platforms take. The next day, Uber Eats added a $3 delivery fee to local orders for customers and reduced the delivery radius of Jersey City’s restaurants.

Now, fewer people are ordering from the restaurants via Uber Eats and instead are shifting to other platforms, the company and the town’s mayor both confirmed to Protocol.29

When cities or states impose a price control on the commissions delivery apps can charge restaurants, they are unknowingly destroying the delicate balance platform owners have struck to attract enough consumers and suppliers on the platform to make the economics work. In cases where the government hasn’t capped commissions and fees across all sides of the platform, the first step for the app owner is to raise fees on consumers to make up for the lost revenue from the restaurant. But as mentioned earlier, the consumer side has a higher elasticity of demand than the restaurant side, so an equivalent price increase will disproportionately decrease demand on that side of the market.

Poorly designed price controls can also have a disparate impact on different business models in the same market. In the food delivery business, for example, there are two common business models with starkly different cost structures. Some companies merely aggregate online orders and leave the restaurant to handle final delivery on its own. The commissions for these services tend to be 15 percent or lower because the costs are much lower than full delivery services. Other services are full stack — they handle the transaction from the beginning of the order until it’s been delivered to the customer. These services charge higher commission rates (up to 30 percent) because paying drivers for their time and expenses is much more costly than merely aggregating online orders. Naive commission caps favor the aggregators over the full stack delivery service providers because the cap is usually non-binding on the low-cost business model. But that low-cost business model is also less innovative. Full-service delivery platforms are reducing transaction costs low enough to bring an entire new category of restaurants into the delivery market.

Price controls would also disproportionately hurt small restaurants. Large chains like McDonald’s negotiate commission rates as low as 15 percent with delivery platforms because they can offer a high, steady volume of orders as well as their own large marketing budgets.30 Smaller restaurants are riskier partners and therefore pay higher commission rates — meaning price controls would disproportionately impact small restaurants. Commission caps might also lead to more vertical integration between restaurant chains and delivery services. Some large chains like Domino’s Pizza already employ their own delivery drivers.31 If enough cities and states implement price controls on third party delivery services, then more chains with high order volumes might decide to bring delivery services in-house to avoid the caps (because there are no commissions in a vertically integrated company).

So, what is the likely effect of these commission caps? Higher consumer fees. Longer wait times. Lower quality service. Reduced restaurant and delivery zone coverage. A switch from full service delivery apps to aggregators. And an increased incentive for the largest restaurant chains to vertically integrate with delivery services.

Lastly, it’s important to note that neither of the two exceptions for the general rule against price controls hold in this case. First, food delivery service markets are highly competitive.32 Most of the companies in this market haven’t been able to reliably turn a profit yet. As Eric Fruits, the chief economist at the International Center for Law and Economics, noted,

Much attention is paid to the ‘Big Four’ — DoorDash, Grubhub, Uber Eats, and Postmates. But, these platform delivery services are part of the larger foodservice delivery market, of which platforms account for about half of the industry’s revenues. Pizza accounts for the largest share of restaurant-to-consumer delivery.33

He goes on to point out that restaurants can also always offer their own delivery service, which serves as a check on the market power of third-party food delivery apps. And restaurants also have the option of apps like ChowNow, Tock, and Olo that offer online ordering as well at substantially lower commissions, largely because they do not offer delivery.

Second, the pandemic is a chronic rather than acute public health emergency. It is now entering its second year and we are still months away from readily available vaccinations for all groups. Price controls would reduce supply at a time when people desperately need delivery services to maintain social distancing.

CONCLUSION: A BETTER WAY FORWARD

While bailouts are never uncontroversial, bailing out the restaurant industry is an easy call. There is no moral hazard risk as there was with the bank bailouts in 2008, when it was reasonable to worry that bailed out financial firms would increase their risky behavior in the future knowing that they would be bailed out in the event of a crisis. In this case, restaurants won’t change their behavior in the future in a way that increases the odds of a deadly pandemic.

A viral pandemic is a perfect example of an exogenous shock — an Act of God (or “force majeure” as insurance contracts put it). By definition, the pandemic affects everyone. Private insurance markets don’t work for pandemics as well as they do for fires or natural disasters because a pandemic occurs everywhere all at once. The private insurance provider would be forced to pay out to all its insured entities simultaneously. Normally,

a majority of an insurer’s clients would be unaffected by an event and their premiums would be used to finance payouts for those harmed. In the case of a pandemic, everyone is harmed.

The federal government is the appropriate entity for collectively insuring the population against these kinds of macro-level risks. Using its fiscal and monetary capacity, the government can efficiently insure the entire population across time. Fiscal support comes in the form of deficit-financed spending (we’re effectively borrowing from our future, richer selves) and monetary support comes in the form of lower interest rates and guaranteed loans for businesses and state and local governments.

Deficit spending will need to be paid for in the future, either via inflation or taxes. But deficit-spending during a crisis is consistent with welfare-enhancing public policy. Income has diminishing marginal returns. In a time of crisis, we want to be able to borrow against our collective future income, which is exactly what deficit spending allows us to do. Just give people money — don’t mess with prices.

The Right Way To Do Student Debt Relief

Since his victory last November, President Biden has faced persistent calls from the left to forgive student loan debt for the 45 million Americans who collectively owe close to $1.6 trillion in loans. The case for some relief is strong: relative to those who pay out of pocket, people who have borrowed for degrees are more likely to be lower-income, Black, and have less family wealth. These factors make some borrowers especially likely to default, which can lead to further worsening of poverty and the racial wealth gap. But many student debt relief proposals are poorly targeted, regressive, and expensive.

Sens. Elizabeth Warren and Chuck Schumer, along with other Democratic lawmakers, have urged Biden to take executive action to forgive $50,000 of student loan debt per borrower. The president likely does not have the authority to spend hundreds of billions of dollars without Congressional approval, but even if he did, enacting this misguided proposal would be deeply regressive. Approximately 48 percent of outstanding student loans are held by people with graduate degrees, which is twice the share of loans held by those who earned an Associate’s degree or less. In fact, more than a third of student loan debt is concentrated among households with annual incomes over $97,000. Absent better targeting, broad debt relief would mostly benefit high-income households that already have the ability to pay off their debts.

When a student asked President Biden at a town hall last week what he would do to forgive at least $50,000 in debt for every borrower, the president admirably and forcefully responded “I will not make that happen.” Instead, Biden said that he would be willing to sign a bill offering up to $10,000 of debt relief to individuals with annual incomes below $125,000 if Congress sent him a bill to do so. Biden’s approach is far more sensible and progressive than that of the left. However, one-time debt cancellation of any size would still be a flawed fix for the crisis of out-of-control higher education costs.

The best way to administer the student debt relief Biden has called for is through an expansion of income-driven repayment (IDR) programs, an idea he endorsed during his presidential campaign. Such programs calculate a borrower’s monthly payment based on their income and other factors, such as family size and location, instead of being based solely on the outstanding balance of loans. Unfortunately, borrowers must opt into one of several IDR programs with complicated terms through a lengthy process. They can also be faced with a hefty tax bill at the end of the repayment period, as any outstanding debt forgiven is considered taxable income. As a result, less than one-third of student borrowers are taking advantage of the benefits of an IDR plan.

Policymakers should replace the existing medley of IDR programs with one new simplified IDR program that allows borrowers to have their debt forgiven tax-free after paying up to 10 percent of their income for 20 years. Payments should also be paused for people who are either unemployed or make less than $25,000 per year. Switching to this progressive system would fulfill Biden’s campaign promise to help distressed borrowers while ensuring that the wealthy pay their fair share. In fact, low-income borrowers with high loan balances could see even more relief under this approach than they would from a one-time $10,000 debt cancellation.

Borrowers who have already entered into existing repayment plans should be given the option to enroll in the new, streamlined plan with minimal administrative burden. Moving forward, new borrowers should be automatically enrolled into the simplified IDR plan and given an option to opt out rather than having to go through a cumbersome process to opt in. Making enrollment automatic for borrowers and simplifying the terms would increase on-time payments and reduce default rates.

But relieving student debt is an incomplete solution. Policymakers must simultaneously take concrete steps to control the skyrocketing cost of higher education, lest the burden of these costs simply moves from students to taxpayers (almost two-thirds of whom do not have the benefit of a college degree to enhance their income). Making community college free, as President Biden has proposed, and expanding aid programs to cover occupational training and apprenticeships would better help students pursuing careers in which a traditional four-year degree isn’t necessary to earn a living wage. Another way to control costs would be to promote three-year degree programs or require greater acceptance of AP/IB credits to reduce the number of courses students need to pay for. Policymakers could also tighten accreditation standards and impose limits on tuition increases for schools receiving federal aid to ensure the students it supports are getting a good return on their investment from high-quality programs.

There are no shortage of good ideas to control future costs, but none of them will help the millions of low-income borrowers who have already incurred crushing debt from our broken higher-education system. Expanding IDR programs and making them work better for borrowers will make repayment affordable for everyone, negating the need for a costly and poorly targeted one-time debt forgiveness. The solution is clear: policymakers should pair an expansion of IDR with cost controls to help both past and future students.

Report Calls for New National Commitment, Vigorous Response to Hunger and Malnutrition in America

WASHINGTON, D.C. — A new brief released today from the Progressive Policy Institute (PPI) targets the federal response to the hunger crisis resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic and recession.

It discusses the valuable policies contained in President Biden’s recent executive orders and the proposed American Rescue Plan legislation and also identifies additional policies to address hunger, including reducing concentration in the food industry, using modern information technologies to help low-income Americans cut through siloed bureaucratic obstacles, and expanding food aid for low-income children.

Key recommendations from the brief include:

• Extend the Pandemic EBT program through the pandemic and economic recovery to provide low-income children with free or subsidized meals during weekends, holidays, and summer break. To be better prepared for a future crisis, Congress should also leverage the P-EBT program to create a permanent authorization for states to issue replacement benefits, giving them more flexibility to respond in a crisis.

• Study the success of the P-EBT program with an eye to converting it into a Summer EBT program post-Covid to bridge the gap in nutrition during the summer months and reach more low-income children in rural and underserved communities.

• Pass legislation, such as the Pandemic Child Hunger Prevention Act, in future recovery legislation, to allow all children free access to breakfast, lunch, and after school snack programs either in school or through “grab and go” and delivery options, as well as reduce bureaucratic barriers for schools to deliver meals to kids.

• Focus on stricter antitrust enforcement in the food industry to help consumers facing increasing prices for basic nutrition staples, such as meat and eggs.

• Use information technology to modernize social service delivery and reduce the administrative burden on low-income people. For example, Congress should enact the HOPE Act, which would create online accounts that enable low-income families to apply once for all social programs they qualify for, rather than forcing them to run a bureaucratic gauntlet.

• Pass the bipartisan Healthy Food Access for All Americans (HFAAA) Act, put forth by Sens. Mark R. Warner, Jerry Moran, Bob Casey, Shelley Moore Capito, which provides incentives, including tax credits or grants, to food providers who serve low-access, rural communities. Draft legislation that provides grants to states to fund the establishment and operation of grocery stores in rural and underserved communities.

Veronica Goodman, PPI’s Director of Social Policy, and Crystal Swann, Senior Policy Fellow, are co-authors of the brief, and said this:

“The Trump administration’s feeble response to America’s hunger crisis was a national disgrace, one of the many ways in which it thoroughly bungled the nation’s response to the Covid pandemic. The contrast with the Biden administration’s sharp focus on hunger and decisive moves to alleviate it couldn’t be more dramatic.

Nonetheless, it should be just the beginning of a new national commitment to wiping out hunger and malnutrition in America. It’s time for a vigorous public response to growing concentration in the food industry, as well as a new push to use modern information technologies to help low-income Americans cut through burdensome bureaucratic obstacles and take charge of their economic security. We’ve also learned lessons during the pandemic for how to provide meals to families outside of the traditional systems, and we should preserve these going forward in the effort to be better prepared for a future crisis and to curb hunger in America.”

Read the full report here.

Hunger in America: A Comprehensive Federal Response

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

This policy brief highlights recent developments in the federal response to the hunger crisis resulting from the Covid pandemic and recession. It discusses the valuable policies contained in President Biden’s recent executive orders and the proposed American Rescue Plan legislation, and also identifies additional policies to address hunger, including reducing concentration in the food industry, using modern information technologies to help low-income Americans cut through siloed bureaucratic obstacles, and expanding food aid for low-income children.

As the pandemic unfolded across the country last spring, one of the first major disruptions was widespread school closures. When teachers locked up their classrooms last March, few thought that a year later schools would still be shuttered. Among the troubling losses to students, especially for the low-income, have been the social services that schools provide, such as meals. Millions of children around the country rely on school for breakfast, lunch, and daytime snacks. In April 2020, as policymakers scrambled to address spiking food insecurity, 35 percent of households with children under 18 said they didn’t have enough to eat, a dramatic rise from already high rates of hunger pre-pandemic. A recent analysis of food insecurity data found that the number of children not getting enough to eat was ten times higher during the pandemic, comparing December 2019 to December 2020.

Food insecurity doesn’t just affect children; adults and the elderly also don’t have enough to eat. Covid relief has certainly helped, but nearly 1 in 6 adults – or close to 24 million Americans – reported that their households did not have enough to eat sometimes or often in the past seven days, according to the latest Census Household Pulse survey in January. Households experiencing food insecurity include close to 5.3 million senior citizens. America’s ongoing hunger crisis requires a forceful response encompassing several different dimensions of public policy.

The sharp rise of hunger during the pandemic is yet another woeful legacy of the Trump administration’s mishandling of the Covid crisis. Last spring, in response to widespread school closures, Congress launched Pandemic Electronic Benefit Transfer, or P-EBT, a program to replace the free and subsidized meals that children would normally get at school. However, the Trump administration placed unnecessary bureaucratic barriers on states which meant that many households eligible for the P-EBT program never received the benefits, even as Congress re-funded the program in September 2020. The Trump administration went so far as to try to kick nearly 700,000 unemployed people off of food assistance late last year in the midst of this public health crisis, but this move was stopped by a federal judge. The consequence of these actions was that while spending for food assistance went up by nearly 50 percent in 2020, some of that aid never reached families in need.

President Biden’s swift call for legislative and executive action on hunger is a welcome sign that U.S. leaders finally are determined to give this problem the attention it deserves.

During his first week in office, President Biden moved quickly to address the acute hunger crisis afflicting millions of Americans during the Covid pandemic and recession. Unveiling his $1.9 trillion coronavirus relief plan in January, Biden struck an urgent note, decrying a reality in which “…folks are facing eviction or waiting hours in their cars — literally hours in their cars, waiting to be able to feed their children as they drive up to a food bank. It’s the United States of America and they’re waiting to feed their kids… But this is happening today, in America, and this cannot be who we are as a country. These are not the values of our nation. We cannot, will not let people go hungry.”

To meet this emergency, Biden’s American Rescue Plan extends the 15% increase in Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits and proposes $3 billion in additional funding for the Women, Infant and Children (WIC) program. The plan also includes $350 billion in aid to state and local governments to support their anti-hunger initiatives, including food pantries, senior nutrition, and other nutrition programming.

President Biden is not waiting for Congressional legislation to provide a much-needed increase in food assistance to families. In his first week in office, the President signed an executive order that will alleviate the hunger crisis in three critical ways.

First, Biden’s executive order will increase food benefits for the P-EBT program by 15 percent, which will give a family of three children an additional $100 every two months, according to National Economic Council Director Brian Deese. The P-EBT was created by Congress in 2020 to give benefits to eligible households with children who would have received free and reduced meals under the National School Lunch Act had schools not been closed. Second, the President has directed the USDA to increase the SNAP Emergency Allotments for those at the lowest rung of the income ladder. And lastly, the executive order calls for modernizing the Thrifty Food Plan to better reflect the cost of a market basket of foods upon which SNAP benefits are based. Collectively, these changes should make food assistance more generous and better targeted.

While these are welcome steps, we call on the Administration to go further by addressing the underlying causes and structural barriers to food access and affordability. We focus on three in particular: Growing concentration in the food industry; siloed social service bureaucracies that make it difficult for low-income Americans to get public assistance; and the difficulty in expanding food aid for low-income children in hard-to-reach places. The pandemic has shined a light on the silent nutrition and food insecurity epidemic in our country and our policy brief outlines a comprehensive federal response.

KEY RECOMMENDATIONS:

- Extend the Pandemic EBT program through the pandemic and economic recovery to provide low-income children with free or subsidized meals during weekends, holidays, and summer break. To be better prepared for a future crisis, Congress should also leverage the P-EBT program to create a permanent authorization for states to issue replacement benefits, giving them more flexibility to respond in a crisis.

- Study the success of the P-EBT program with an eye to converting it into a Summer EBT program post-Covid to bridge the gap in nutrition during the summer months and reach more low-income children in rural and underserved communities.

- Pass legislation, such as the Pandemic Child Hunger Prevention Act, in future recovery legislation, to allow all children free access to breakfast, lunch, and after school snack programs either in school or through “grab and go” and delivery options, as well as reduce bureaucratic barriers for schools to deliver meals to kids.

- Focus on stricter antitrust enforcement in the food industry to help consumers facing increasing prices for basic nutrition staples, such as meat and eggs.

- Use information technology to modernize social service delivery and reduce the administrative burden on low-income people. For example, Congress should enact the HOPE Act, which would create online accounts that enable low-income families to apply once for all social programs they qualify for, rather than forcing them to run a bureaucratic gauntlet.

- Pass the bipartisan Healthy Food Access for All Americans (HFAAA) Act, put forth by Sens. Mark R. Warner, Jerry Moran, Bob Casey, Shelley Moore Capito, which provides incentives, including tax credits or grants, to food providers who serve low-access, rural communities. Draft legislation that provides grants to states to fund the establishment and operation of grocery stores in rural and underserved communities.

GO BIG ON HUNGER — FAST

Food insecurity is not just a moral issue, it also has economic and social costs. Adults who go hungry are less productive and are more likely to suffer from chronic illness. The nutrition crisis has been called a “slow epidemic” by Dr. Dariush Mozaffarian, dean of the Freidman School of Nutrition Science and Policy at Tufts University.

The rate of households reporting that they do not have enough to eat is much higher than pre-pandemic levels, especially for families with children. Hungry children are more likely to get sick and fall behind in school. One in five Black and Hispanic households report they are unable to afford food. Poor nutrition and soaring rates of metabolic disease are a drag on the economy and contribute to rising healthcare costs and early deaths in minority and low-income families that are disproportionately more likely to experience poor nutrition and health as a result of food insecurity.

Food assistance spending now can also speed economic recovery. A 2019 report from the U.S. Department of Agriculture quantified the economic impact of SNAP spending during the Great Recession and found that this program can serve as an “automatic stabilizer” during a downturn. The authors analyzed program data and observed that low-income SNAP participants quickly spent the benefits after receiving them and the overall effect was a boost in the economy. Every $1 billion in new SNAP benefits led to “an increase of $1.54 billion in GDP – 54 percent above and beyond the new benefits.” SNAP benefits also generated $32 million in income for the agriculture industry and helped create jobs.

BUILDING RESILIENCE INTO OUR ANTI-HUNGER POLICIES

Despite the pandemic’s many tragic aspects, the disruption of our everyday lives has had some silver linings. Many innovations have been born of necessity, such as pioneering new approaches to feeding children who rely on meals at school despite school closures, and these can inform how we tackle food insecurity going forward.

The U.S. has a patchwork of programs to feed children, and the efficiency of this system has been sorely tested during the pandemic. The School Breakfast Program and the National School Lunch Program feeds over 22 million children per year who rely on meals provided by their schools as a significant source of nutrition. During a normal schoolyear, the lack of access during weekends, holidays, and summer break can leave kids hungry. During the summer, only 1 in 6 of these children still receive meals through the USDA Summer Food Service Program. In 2011, in response to this gap in nutrition, the USDA launched a pilot called the Summer EBT to provide meals to children during the summer months. The program is aimed at reaching low-income families in rural and hard-to-reach communities where the Summer Food Service Program has not been as successful. Results from the demonstration are promising and, so far, more than 250,000 children have gained access to nutrition as a result of the program. Despite the early successes of the Summer EBT demonstration projects, the Trump administration took the controversial step of closing sites in some places, such as Connecticut and Oregon.

Some researchers have called for expanding the Pandemic-EBT program through the rest of the pandemic and recovery to allow states to provide free or subsidized meals for children during these breaks in the school calendar. Once schools reopen, the Biden administration should explore preserving the systems set up by schools during the pandemic to provide meals to low-income children outside of the usual school day and year, including potentially by expanding Summer EBT.

Forced to improvise when schools shut down, many school districts have developed more flexible and varied ways to get meals in the hands of hungry families. School meals now are more widely available to children learning at home through “grab and go” distribution centers or meal delivery. School systems should go further to ensure that other family members in low-income households can take away meals during pickup to eat off-site. For example, Rep. Suzanne Bonamici has co-sponsored a bill that would allow schools to distribute meals to students and other community members in need, and to extend meal service for afterschool meals and snack programs. We applaud this bill as temporary and essential pandemic-relief legislation. This flexibility and the waivers aimed at making it easier to serve meals for low-income families in school districts could end up having unintended consequences, such as impacting funding levels as these waivers are used to determine need across districts. Policymakers should remain aware that funding will need to be determined differently during the pandemic as a result of fast-changing policies.

We do not know when the next pandemic or economic crisis may strike, but we can be better prepared. As we’ve learned from Covid, systems that we take for granted, such as schools, can be shut down overnight. In order to stay ahead of a future crisis, researchers at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities have suggested that Congress “leverage the P-EBT structure to create a permanent authorization for states to issue replacement benefits (similar to P-EBT, and perhaps renamed “emergency-” or E-EBT) in case of lengthy school or child care closures resulting from a future public health emergency or natural disaster.” This will make it easier for states to act quickly and not rely on Congressional action should schools need to close in the future.

Making our food delivery system more resilient against future pandemics or other emergencies should be a national priority. That will require attacking the structural roots of food scarcity in the world’s richest country.

STRUCTURAL BARRIERS TO FOOD ACCESS AND AFFORDABILITY

Of course, America’s hunger problem did not start with the pandemic. Before Covid, as many as 13.7 million households or 10.5 percent experienced food insecurity. In addition to dealing with the present crisis, the White House should develop new strategies for tackling the structural causes of food access and unaffordability. Three stand out today in particular: a decades-long trend of concentration in the food industry; bureaucratic inertia and dysfunction that discourages enrollment in aid programs; and the stubborn blight of rural hunger.

As PPI economist Alec Stapp has documented, market concentration in the food industry is driving up prices for basic sources of protein, such as chicken and eggs. A recent antitrust conference at Yale Law School noted that “the country’s four largest pork producers, beef producers, soybean processors, and wet corn processors control over 70 percent of their respective markets. Four companies control 90 percent of the global grain trade. Agrochemical, seed, and many consumer product industries are likewise now controlled by just a few mega-sized firms.”

Low-income households spend the bulk of their budgets on housing, transportation, and food and, as a share of their household income, these families spend close to a third on food, with meat and eggs being especially pricey. To make food more affordable for all families, the White House should focus on stricter antitrust enforcement in the food industry by appointing leaders to the USDA, the Antitrust Division of the Department of Justice, and the Federal Trade Commission who will make this issue a priority.

Recent evidence from communities hit especially hard by the pandemic also highlights how formidable bureaucratic barriers deter many eligible households from accessing food aid. Policymakers should use information technology to modernize social service delivery and reduce the administrative burden on people to increase take-up in food assistance programs.

PPI has called for modernizing safety net programs to reduce the high “opportunity costs” of being poor in America. Federal and state governments should adopt modern digital technologies that help low-income families apply once for public benefits without having to run a bureaucratic gauntlet of siloed programs for nutrition, housing, unemployment, job training, mental health services, and more.

“While it’s true that government safety net programs help tens of millions of Americans avoid starvation, homelessness, and other outcomes even more dreadful than everyday poverty, it is also true that, even in ‘normal times,’ government aid for non-wealthy people is generally a major hassle to obtain and to keep,” notes Joel Berg, CEO of Hunger Free America.

“Put yourself in the places of aid applicants for a moment,” Berg added. “You will need to go to one government office or web portal to apply for SNAP, a different government office to apply for housing assistance or UI, a separate WIC clinic to obtain WIC benefits, and a variety of other government offices to apply for other types of help—sometimes traveling long distances by public transportation or on foot to get there—and then once you’ve walked through the door, you are often forced to wait for hours at each office to be served. These administrative burdens fall the greatest on the least wealthy Americans.”

In a 2016 PPI report, Berg proposed the creation of online “HOPE” accounts for families to better manage and access their benefits, and into which they could deposit their public assistance.

This idea is at the heart of the Health, Opportunity, and Personal Empowerment (HOPE Act) introduced by Reps. Joe Morelle (D-NY) and Jim McGovern (D-Mass) and Senator Kirsten Gillibrand (D-NY). The HOPE Act would fund state and local pilot projects setting up online HOPE accounts to make it easier for low-income people to apply for multiple benefits programs with their computer or mobile phone. In addition to saving them time, money, and aggravation, HOPE accounts enable people to manage their benefits – effectively becoming their own “case manager” – and easing their dependence on often inefficient and unresponsive social welfare bureaucracies.

WIC (formally the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children) is a concrete example of how bureaucratic barriers can impact program enrollment. Despite increases in funding and strong evidence for its boost in outcomes for mothers and children, the share of eligible household participating in the program has fallen over the past ten years. One significant barrier to uptake is the requirement that families take time off of work to apply in person and bring their children to multiple appointments at clinics. HOPE accounts, if implemented well, could help families by creating an online platform where they can complete an initial application and better manage their benefits.

Policymakers should also make it easier for the elderly and other vulnerable groups to navigate eligibility and participate in SNAP. Researchers recently found that “providing information on eligibility or information plus application assistance” can significantly increase take-up rates among the elderly. Interventions should be designed with the behavioral differences of eligible groups for various social safety net programs, including food assistance.

The third major contributor to food insecurity is geography. According to the USDA, nearly 40 million Americans live in rural communities considered “food deserts” because they lack a nearby grocery store or food pantry or bank. And although rural communities make up 63% of counties in the U.S., they represent 87% of counties with the highest rates of food insecurity. These “food deserts” tend to disproportionately impact the rural poor, Black and Hispanic households, and families with children. To address this disparity, some organizations have launched mobile food pantries and food delivery programs that ship food in bulk to low-income families, but more access is needed to bridge this geographical barrier.

Earlier this month, Senator Mark Warner, along with several senators from both sides of the aisle, introduced the Healthy Food Access for All Americans (HFAAA) Act which provides incentives, including tax credits or grants, to food providers who serve low-access communities and become designated as a “Special Access Food Provider” certification process through the U.S. Treasury Department. This legislation is a crucial way to incentivize food providers to set up shop in rural and hard-to-reach communities.

CONCLUSION

The Trump administration’s feeble response to America’s hunger crisis was a national disgrace, one of the many ways in which it thoroughly bungled the nation’s response to the Covid pandemic. The contrast with the Biden administration’s sharp focus on hunger and decisive moves to alleviate it couldn’t be more dramatic.

Nonetheless, it should be just the beginning of a new national commitment to wiping out hunger and malnutrition in America. It’s time for a vigorous public response to growing concentration in the food industry, as well as a new push to use modern information technologies to help low-income Americans cut through burdensome bureaucratic obstacles and take charge of their economic security. We’ve also learned lessons during the pandemic for how to provide meals to families outside of the traditional systems, and we should preserve these going forward in the effort to be better prepared for a future crisis and to curb hunger in America.

The President’s address to Congress is an opportunity to highlight Covid-19 treatments

The United States broke records with the swift development and distribution of new Covid-19 vaccines, but after the Trump administration’s hydroxychloroquine debacle, the focus on treatments was pushed to the side. President Biden has acknowledged that even with the new vaccines, the Covid-19 pandemic will likely linger throughout the year. To save lives, we’ll need to increase access to evidence-based treatments by educating the public, restructuring treatment facilities to handle Covid-positive patients, and helping patients navigate the health care system. Federal leadership will be essential to meet these goals.

President Biden has spent the first few weeks of his presidency ramping up Covid-19 response efforts. He signed an executive order requiring mask-wearing in all federal buildings, called for a $1.9 trillion economic recovery package, and pushed to increase vaccinations to 1.5 million per day. But one thing he hasn’t drawn a lot of attention to is treating patients with Covid-19 infections.

Even as new cases have plummeted in recent weeks, more than 1,000 Americans per day are dying from Covid-19. And because the country isn’t likely to return to ‘normal’ until the end of the year, it’s important to not lose sight of the important role effective Covid-19 treatments can play in reducing unnecessary deaths. Two drugmakers – Eli Lilly and Regeneron – have developed monoclonal antibody therapies that lessen the effects of Covid-19 on high-risk patients. Increasing access to these treatments will save lives.

Next week at his State of the Union address, President Biden will emphasize his Covid-19 recovery plan. He should use the bully pulpit of the presidency to emphasize that evidence-based therapies are available to people who get infected.

Recent research from Baylor University Medical Center published in the Journal of the American Medical Association found that monoclonal antibodies reduced hospitalizations among high-risk Covid-19 patients. However, to be effective, it was important that these high-risk patients – those over 65 or with obesity or diabetes or immunocompromised – received the therapy early in the course of their illness. This means that doctors need to be aware of and prescribe the treatment and patients need access to infusion facilities since the drugs are delivered intravenously within the first 10 days of symptoms.

Yet uptake of these effective therapies remains low. There are four main hurdles:

- With everchanging clinical guidelines for Covid-19, many physicians aren’t aware of the efficacy of these new treatments and thus aren’t prescribing them to patients

- Stand-alone infusion centers require referrals from physicians and may be hesitant to accept Covid-positive patients

- Hospitals are overburdened with critically ill Covid-19 patients and vaccination efforts and haven’t set up out-patient infusion centers where patients can easily be treated

- It’s difficult to identify and treat patients within the 10-day window from the onset of symptoms

There are steps the new administration can take to improve access to these therapies which will in-turn save lives and lessen the impact of the pandemic.

First, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) should work with state licensing boards to ensure the timely dissemination of clinical information to providers on the ground. Because guidelines are evolving as we learn more about Covid-19, it’s important that there are clear communication channels to get information to individual providers across all states. While it makes sense for the CDC to act as a central gathering place of information, providers should not have to be checking the CDC website daily in order to stay up to date.

Second, infusion centers need to adapt to Covid-19. Given the importance of receiving treatments within 10 days of the onset of symptoms, infusion centers need to update their practices to expedite the treatment process. That might mean working to build relationships with individual providers so that they know where to refer Covid-positive patients and changing their protocols to accept walk-ins without appointments. They also need to make sure they have the infrastructure needed to treat Covid positive patients and keep them separate from patients receiving other types of infusions.

Third, as daily cases have dropped, hospitals should shift their focus from treating Covid-19 inpatients patients to helping treat Covid-19 patients in the outpatient setting. Typically, hospital infusion centers are for administering cancer drugs. Restructuring infusion facilities so that they can be safe for Covid-positive patients and cancer patients will be an important step to getting more people treatment.

Finally, contact tracing, testing and diagnosing Covid-19 patients in a timely fashion remains as important as ever. Patients need to know they are Covid-19 positive within a few days in order to be able to benefit from monoclonal antibody therapies. Continued investment in contact tracing and testing will make fast diagnoses possible. But after a patient receives a positive Covid-19 test either from a doctor’s office, public testing site, or a pharmacy, there needs to be a pipeline to a care provider and treatment, if needed. Monoclonal antibody therapies require a prescription and a referral and often patients will have to drive to an infusion site. Making sure the patient is easily transferred between care sites will be vital to timely access to treatment.

There is no question that the pandemic is improving. But with President Biden’s admission that Covid-19 is likely to drag on in the coming months, it is vital that people know more about treatment opportunities. Monoclonal antibody therapies are out there and should be available to everyone — not just the well-informed health care consumer or the elites. The president has made effective use of his bully pulpit to encourage mask-wearing and vaccinations. He should do the same with Covid-19 therapies.

This blog was also published on Medium.

Biden should ease access to key opioid treatment

From May 2019 to May 2020 the CDC reported over 81,000 overdose deaths from opioids in the United States, the biggest annual death toll to date. In a belated effort to mitigate the crisis, the Trump administration changed regulations to make it easier to access the opioid treatment drug buprenorphine in the waning days of his presidency. But the new Biden administration has reversed those changes because of legal concerns over the way the Trump administration implemented the policy.

The Trump changes were released amidst the chaos of the Capitol insurrection. When Elinore McCance-Katz, the health and Human Services (HHS) assistant secretary for mental health and substance use, resigned in the aftermath of the riots, the White House quickly appointed a replacement who greenlighted new “clinical guidelines” that made it easier for physicians to prescribe buprenorphine. McCance-Katz had refused to push these changes forward during her tenure. McCance-Katz had favored more safeguards to prevent buprenorphine from being overprescribed in fear of the drug starting a new epidemic of its own.

Buprenorphine is one of three pharmacological treatments for opioid use disorders and is considered the easiest tolerated of the options. It has been shown to reduce overdose mortality by 50% and comes in a variety of forms, dissolvable films, and tablets being the most common. But stringent regulations make the drug difficult to get for people seeking opioid treatment. Under current law, doctors are required to complete special training and obtain an “X-waiver” license in order to prescribe buprenorphine. Only 5% of doctors in the country have the necessary waiver to prescribe it, and in rural areas, it’s even less.

The new guidelines allowed any physician with a Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) prescriber license to prescribe buprenorphine. The drug is a narcotic that diminishes the symptoms of opioid withdrawal and is also safer, less addictive, and less likely to be misused. Despite its safety and efficacy, The federal government crafted these rules over two decades ago before the drug was approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat opioid use disorder in 2002. Ironically, opioids require no special training to be prescribed, unlike buprenorphine.

Many addiction researchers, physicians, and policy experts applauded the change in regulation. In the hasty process, however, the Trump administration did not obtain the necessary approval to change the regulations from the White House Office of Management and Budget (OMB).

Though the Trump administration may not have followed proper procedures, Biden’s decision to reverse its action sparked backlash from many policymakers and physicians who believe quick and drastic measures must be taken to ease the toll of the pandemic for people with substance use disorders.

Overdose deaths have been steadily rising in the past decades and the pandemic has significantly exacerbated the rate. Synthetic opioids are believed to be the main substance that accelerated the overdose death rate during the pandemic. The CDC reported that two-thirds of opioid overdose deaths involve synthetic opioids. Experts estimate that the total economic burden of the crisis is over $78 million per year.

In addition to limited providers, people with substance use disorders often face other barriers to receiving treatment, especially in disadvantaged communities. These include lack of stable housing, health insurance, and stigma. COVID-19 intensified these problems by limiting in-person support groups, public transportation, and job security while increasing social isolation and stress.

Since buprenorphine is an opioid it does have the potential to be addictive. It is, however, safer and less addictive than the opioids that it is used to treat because of its pharmacological properties. It is also unlikely that the deregulation of this drug will lead to more opioid use disorders since it is only prescribed to treat opioid use disorders– unlike other opioids that are prescribed to alleviate pain. Ultimately the life-saving benefits that buprenorphine offers far outweigh the potential risks.

Although the legal concerns over the way the Trump Administration removed these regulations are legitimate, the longer it takes the Biden administration to ease the restrictions on buprenorphine – or find an equivalent treatment – the direr the situation will become.

As a part of launching his multifaceted Opioid Crisis plan, President Biden should take executive action to remove X-Waivers in a legally surefire and quick manner. While removing the waivers will not solve the crisis overnight, it is a step in the right direction to treat people with opioid use disorders and prevent the overdose death rate from rising further.

This piece was also published in Medium.

The Progressive Way to Ease Student Debt Burdens

Sens. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) and Chuck Schumer (D-N.Y.) want to give up to $50,000 in debt relief to every American with student loans. Though they claim to be progressives, there is nothing progressive about this. It would benefit households in the top half of the income scale far more than those in the bottom half. Almost half of those with student debt have graduate degrees, after all.

It’s no wonder so many working-class voters have abandoned the Democratic Party. Bailing out college graduates with decent incomes will convince many that the Republicans are correct: The Democrats are elitists who don’t care about those without college degrees.

President Biden proposes to forgive only $10,000 in student debt, targeted to borrowers from low-income families. That is a more progressive approach, but it won’t help those who never went to college. According to the Census Bureau, only roughly 36 percent of Americans over age 25 have four-year college degrees, while 38 percent never attended a day of college. Only 20 percent of U.S. households have student debt.

With a little creativity, the president could help needy borrowers while also investing in non-college goers. Specifically, the administration should propose $10,000 per person in “career opportunity accounts” for working Americans aged 18 to 55 who earn less than $75,000 a year. Roughly two-thirds of all full-time, year-round workers earn less than $75,000. (To avoid penalizing those who earn just over $75,000, the money could be phased out between $70,000 and $80,000.)

Read the full piece here.

The Progressive Way to Slash Child Poverty

Written by Veronica Goodman and Ben Ritz

On Monday, congressional Democrats unveiled a proposal to dramatically expand the Child Tax Credit (CTC), one of the bigger policies in President Biden’s $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan. On the same day, Sen. Mitt Romney (R-Utah) gave the concept bipartisan backing by offering a Republican proposal for turning the CTC into an expanded child allowance. Both proposals would raise the current benefit from $2,000 per child to $3,000, provide additional credit for children under age six, make the full value of the benefit available for low-income families, deliver the payments in a monthly installment instead of a lump sum at the end of the year and dramatically reduce child poverty in America.

It’s no surprise that policymakers in both parties are prioritizing child poverty. As many as one in seven children, or close to 11 million, are poor. The United States consistently has among the highest levels of child poverty among the world’s wealthiest countries, many of which offer so-called “child allowances” to support low-income parents. The Democratic proposal would not just help these kids in the short term by lifting an estimated five million children out of poverty. It would also have long-run benefits for social mobility and support Black and Hispanic families the most. This Democratic proposal is estimated to cut child poverty nearly in half while the Romney proposal would reduce it by one-third.

Read the rest here.

Many Roads to a Living Wage

The Congressional Budget Office has dealt another blow to progressive hopes for swift action to raise the U.S. minimum wage to $15 an hour. It released a new study this week estimating that while the wage hike would lift 900,000 Americans out of poverty, it also would cost 1.4 million workers their jobs.

Liberal economists challenged the job loss figures, calling CBO’s methodology outdated. But the report feeds growing doubts that Senate Democrats will be able to shoehorn the measure into the big relief bill they hope to pass under “reconciliation” rules that allow for a simple majority vote. That means Republicans could filibuster it to death.

These setbacks raise an important tactical question: In a commendable effort to give working Americans a raise, are progressives fixating too narrowly on the minimum wage? After all, there are other policy tools at their disposal that could lift workers’ earnings without sacrificing jobs or harming small businesses. And these policies — essentially rewards for work delivered through the tax system — could be taken up under reconciliation.