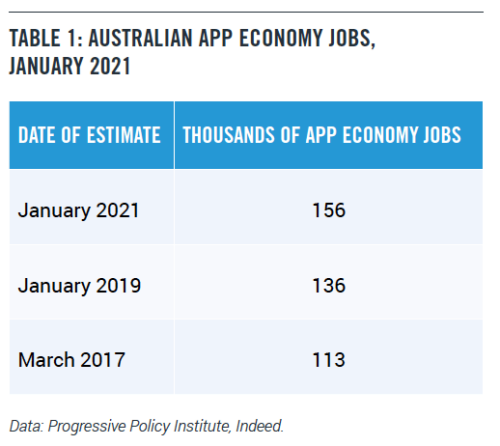

In this blog, we update our November 2018 estimate of Canadian App Economy jobs. Much the same as other countries, the Canadian economy has suffered an economic shock from the Covid-19 pandemic, with Statistics Canada estimating the country’s output contracting by 5.4 percent in 2020. But the App Economy, which has a history of being recession resistant, has been a steady source of job growth through the economic turbulence. As of November 2020, we estimate the Canadian App Economy included 309,000 App Economy jobs, an 18 percent increase from our November 2018 estimate of 262,000 jobs (Table 1). By comparison, overall Canadian employment declined over the same stretch.

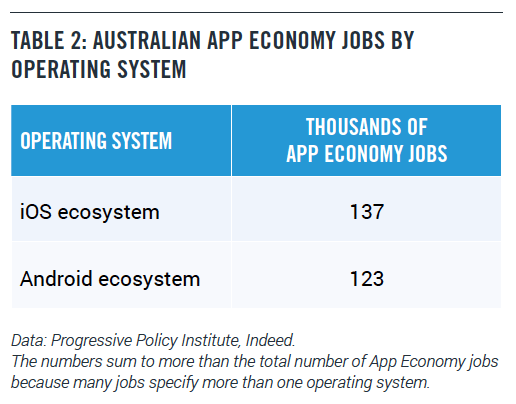

We also estimate Canadian App Economy jobs by mobile operating system. As of November 2020, we estimate the iOS ecosystem included 243,000 App Economy jobs and the Android ecosystem to have 247,000 App Economy jobs. That’s an increase of over 20 percent for both the iOS and Android ecosystems compared to our last estimates. The iOS and Android numbers sum to more than the total because many App Economy jobs can belong to both ecosystems.

Methodology

For this research, a worker is in the App Economy if he or she is in:

- An IT-related job that uses App Economy skills—the ability to develop, maintain, or support mobile applications. We will call this a “core” App Economy job. Core App Economy jobs include app developers; software engineers whose work requires knowledge of mobile applications; security engineers who help keep mobile apps safe; and help desk workers who support use of mobile apps.

- A non-IT job (such as sales, marketing, finance, human resources, or administrative staff) that supports core App Economy jobs in the same enterprise. We will call this an “indirect” App Economy job.

- A job in the local economy that is supported either by the goods and services purchased by the enterprise or by the income flowing to core and indirect App Economy workers. These “spillover” jobs include local professional services such as bank tellers, law offices, and building managers; telecom, electric, and cable installers and maintainers; education, recreation, lodging, and restaurant jobs; and all the other necessary services. We use a conservative estimate of the indirect and spillover effects.

We estimate the number of App Economy jobs by combining annual data on ICT professionals in Canada from Statistics Canada and Employment and Social Development Canada with comprehensive counts of “App Economy” job openings in Canada from ca.indeed.com. Our methodology is described In detail in the Appendix to our 2017 paper on the European App Economy, including our technique for combining both French and English terms for App Economy jobs.

Geography

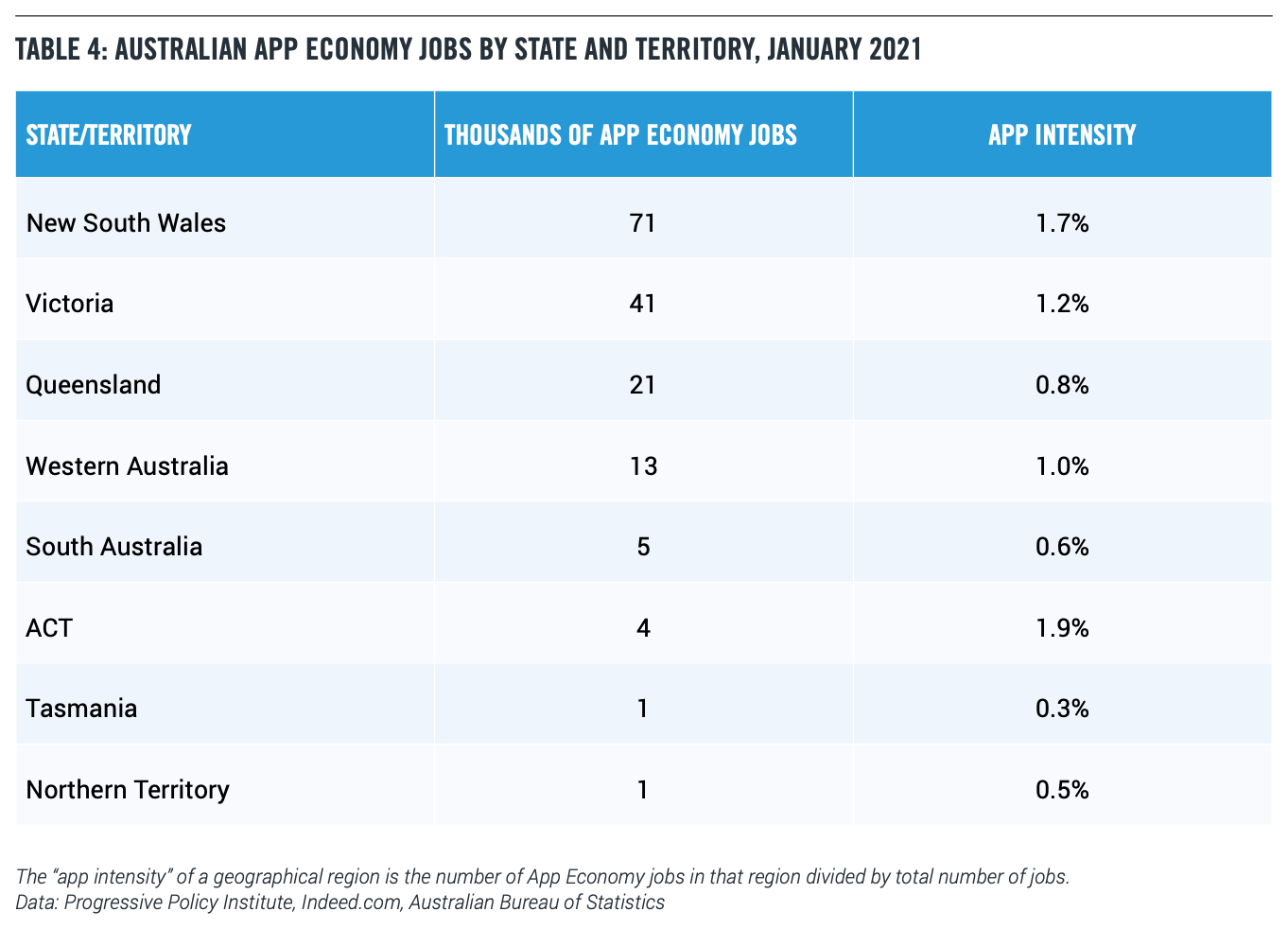

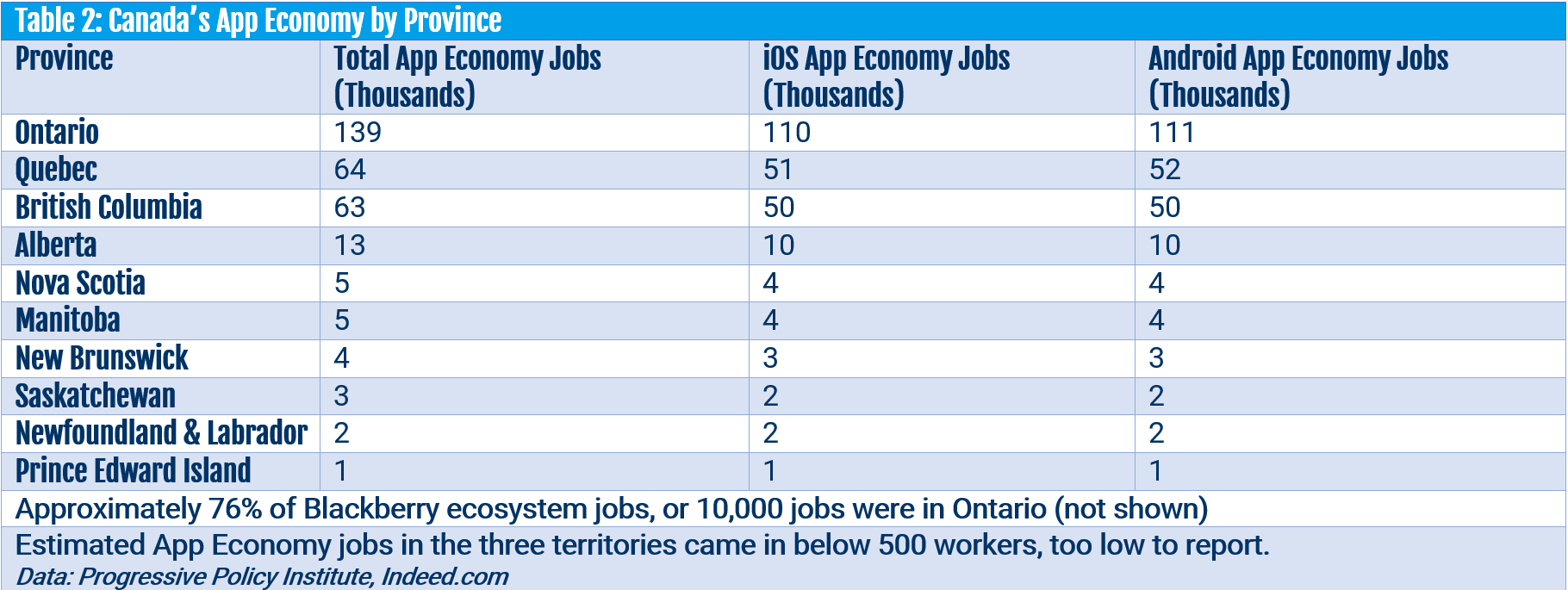

Our methodology enables us to estimate App Economy jobs at the provincial level by ecosystem. Not surprisingly, Ontario leads with 139,000 App Economy jobs (Table 2). Coming in second and third, respectively, was Quebec with 64,000 App Economy jobs and British Columbia with 63,000 App Economy jobs. Since our last estimate, total App Economy jobs in Ontario remain nearly the same, while App Economy jobs in Quebec are up 20 percent. British Columbia was the fastest growing province among the top three, with over a 50 percent increase compared to our November 2018 estimate.

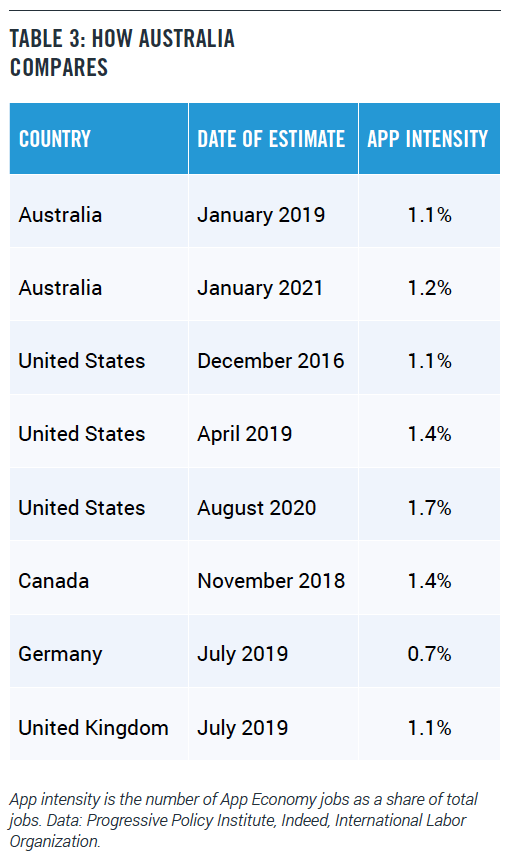

Our methodology allows us to make international comparisons as well. Compared to our estimates of total App Economy jobs in other countries, Canada’s 309,000 App Economy jobs is nearly double the size of Australia’s App Economy (Table 3). In absolute terms, Canada’s App Economy is significantly smaller than the United States.

Adjusting for country size, Canada is doing very well. “App intensity” is defined as the number of App Economy jobs divided by total employment. Canada’s app intensity of 1.7 percent ties with the United States and outpaces Australia, two countries where we have recent “pandemic” estimates. Note that app intensity has risen during the pandemic because the number of app economy jobs has risen even as the broader employment numbers have shrunk.

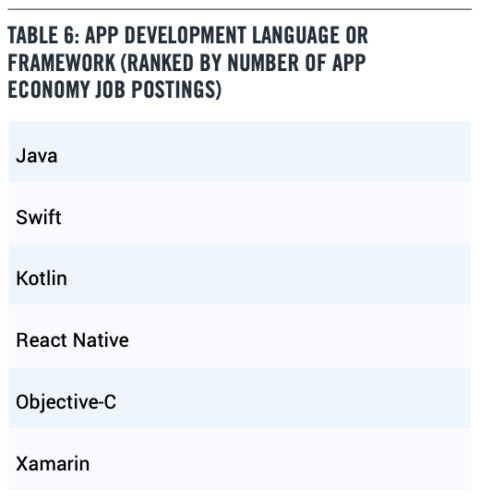

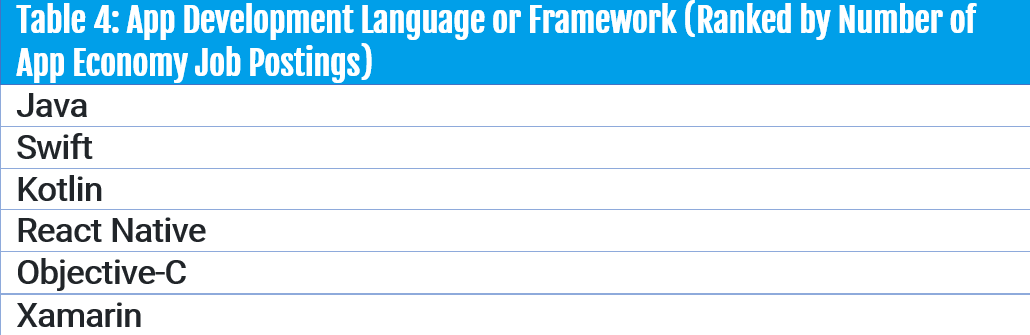

Finally, we note that many core App Economy jobs require familiarity not only with iOS or Android, but with one of the app development languages or frameworks, such as Swift (iOS) or Kotlin (Android).

Table 4 below presents a list of app development language and frameworks, ranked by the number of mentions on App Economy job postings. Java is first, followed by Swift. Because the methodology is new, we are not yet ready to quantify the list.

Examples

In this section we note some current examples of companies and sectors that have been recently in the market for workers with App Economy skills. One sector which is attracting a wave of App Economy jobs is finance. As of March 2021, Sun Life Financial was hiring a senior iOS developer in Montreal, Quebec. Fintech company Paytm, which reached 1.2 billion global monthly transactions in February, was searching for a mobile iOS engineer in Toronto, Ontario. Royal Bank of Canada was seeking a senior iOS developer in Toronto, Ontario. The National Bank of Canada was looking for a mobile product designer to design and prototype iOS and Android mobile experiences in Montréal, Quebec. Cryptocurrency exchange firm Exchangily was hiring a mobile app developer proficient in Dart or Flutter in Markham, Ontario. Payment processor Square was searching for an engineering manager with expertise in Kotlin and Swift in Toronto, Ontario.

Equitable Bank was seeking a senior development manager with knowledge of iOS and Android in Toronto, Ontario. Fintech company Mogo Finance Technology, which recently acquired saving and investing app Moka Financial Technologies, was looking for a senior iOS engineer in Vancouver, British Columbia. Neo Financial was hiring a software development engineer to run automated iOS and Android tests in Calgary, Alberta. Tangerine Bank was searching for a senior mobile product designer with knowledge of iOS and Android interfaces in North York, Ontario. Olympia Financial Group was seeking an IT service desk analyst with experience troubleshooting iOS in Calgary, Alberta. Financial advisory company BDO was looking for a senior cybersecurity consultant with iOS and Android experience in Ottawa, Ontario. PayBright was hiring a test engineer with experience in iOS and Android mobile testing in Toronto, Ontario.

The health and wellness sector is spurring App Economy employment as well, due in part to Covid-19. For instance, mental health company LivNao, which developed contact tracing app ConTrac in response to the Covid-19 pandemic, was looking for an Android software engineer in Vancouver, British Columbia. Toronto East Health Network was hiring a junior technical associate responsible for the deployment, maintenance, and support of iOS and Android applications in its vaccination clinic in Toronto, Ontario. Charlie Wellbeing, which specializes in mental health counseling for teens, was searching for an iOS developer in Vancouver, British Columbia. Medical supply company Natus Medical Incorporated was seeking a senior firmware engineer with Android experience in Ottawa, Ontario. Carefor Health & Community Services was looking for an IT telecommunications administrator with knowledge of the Android operating system in Ottawa, Ontario. Jump rope company Crossrope was hiring a senior backend software developer to support Android app development in Toronto, Ontario.

Audiometry company SHOEBOX Ltd. was searching for an engineering manager with experience developing and deploying iOS apps in Ottawa, Ontario. Dermatology technology firm MetaOptima was seeking an Android developer in Vancouver, British Columbia. Medical device company Flosonics Medical, which developed the wireless peel-and-stick sensor FloPatch that allows doctors to monitor patients’ bloodflow, was looking for a senior iOS developer in Toronto, Ontario. Repair Therapeutics was hiring an IT support specialist with experience in iOS and Android in Montreal, Quebec. Healthcare technology firm AceAge, which developed medication organizer Karie, was searching for a software developer with experience building mobile applications for Android. Cercacor Laboratories, which develops and licenses non-invasive hemoglobin monitoring systems for athletes and trainers, was seeking a senior iOS engineer in Vancouver, British Columbia. Custom vitamin and supplement manufacturer VitaminLab was looking for a UX designer to support Android and iOS development in Victoria, British Columbia.

Summary

Canada’s App Economy stands poised to be a powerful force for job growth as the country recovers from the Covid recession. Its 309,000 App Economy jobs are only the start.