This piece is part of our Building American Resilience Series.

Resilience is the ability to react quickly to unexpected events. Market economies are inherently resilient because they are decentralized. But by outsourcing too much production to the rest of the world, the U.S. has traded much of its flexibility and resilience for somewhat lower short-run prices. Moreover, we’ve reduced our ability to deal with new sources of unexpected events, including climate change, pandemics, and wars.

Our inability to produce enough N95 masks for healthcare workers, months into the pandemic, is both astonishing and instructive. N95 masks are classic examples of what might be called “middle-tech”—the masks themselves are individually cheap to produce and have no moving parts or electronic components, but the machines to make the masks, including the special non-woven fabric that filters out tiny particles, are precise pieces of equipment that are expensive, time-consuming to build and mainly come from overseas. A resilient manufacturing sector has to have the know-how and the capabilities to build more machines if needed—and it may be that we no longer have enough of the suppliers with the necessary know-how and capabilities to increase our productive capacity in a crisis.

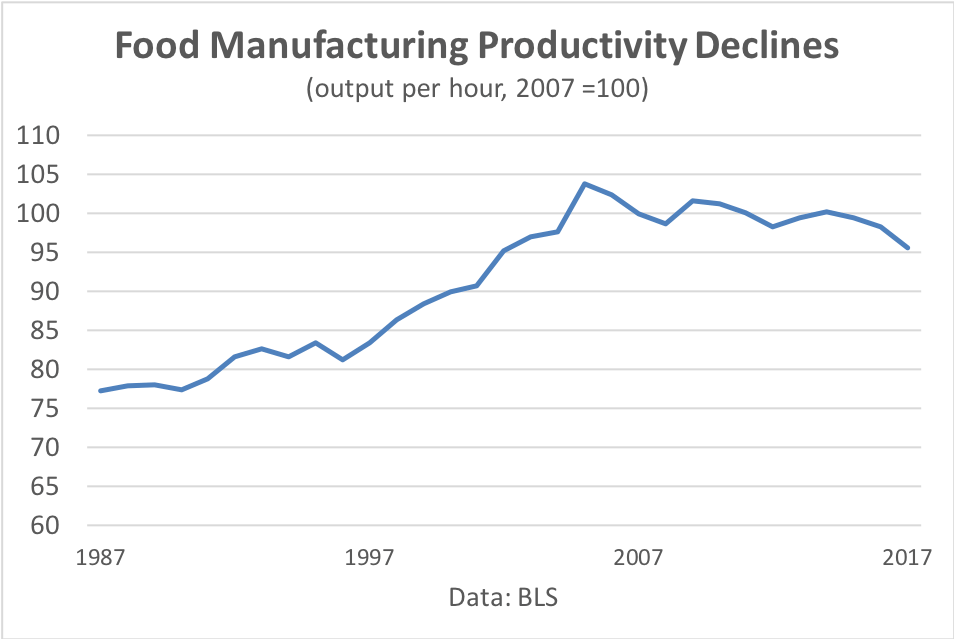

Government statistics clearly show our eroding manufacturing base. Twelve out of nineteen major manufacturing industries shrunk between 2007 and 2019. Over the same stretch, the non-oil goods trade deficit grew by 60% to record levels, showing the gap between what we produce and what we need, and how unprepared we are to deal with potential shocks.

That’s why we propose a “National Resilience Council” to lead a national push to stimulate local production, shorten supply chains, create high-wage factory jobs and make our manufacturing sector more resilient in crises. We have to harness our strength in tech to transform manufacturing for the 21st century. To be honest, we can’t and shouldn’t fight this battle on China’s ground of giant factories supported by government subsidies.

Instead, a resilient manufacturing recovery requires the fostering of flexible, local, distributed manufacturing—relatively small efficient factories that are spread around the country, using new technology, knitted together by manufacturing platforms that digitally route orders to the nearest or best supplier.

The National Resilience Council would be tasked with identifying those industries and capabilities that are strategic, in the sense of improving the ability of the economy to deal with shocks like pandemics, wars, and climate changes. These areas are likely to be underinvested by private sector companies, who quite naturally don’t have an incentive to tackle these sorts of large-scale risks. For example, no single company has an incentive to invest in improving N95 mask technology so that it is easier to scale up production, but the US government does. Or to harken back to an important historic example, the Defense Department’s original motivation for funding the research that led to packet switching and the Internet was to create a decentralized network that would be more survivable in case of nuclear attack.

Shorter, simpler supply chains also help with sustainable production. Long and complicated supply chains require more air and water transportation, generating more greenhouse gases. International shipping alone, especially container ships, accounts for about 2 percent of all carbon dioxide emissions, about the same as Germany. Beyond that, the more links in the supply chain, the more difficult it is for end producers to get a full picture of their carbon emissions.

Our initiative has four parts:

• First, we should double the National Science Foundation’s roughly $8 billion budget, with more of an emphasis on manufacturing-related areas such as materials sciences. That would still put it well below the roughly$40 billion going to the National Institutes for Health.

Such a doubling has been a consistent bi-partisan goal in the past, yet the U.S. has consistently fallen short. For the past two decades more than two-thirds of U.S. private and public R&D spending has gone to infotech and biosciences, while other areas of science and technology have received much less attention. It’s time to make up the shortfall.

• Second, the government can shore up the nation’s supplier base by providing $200 million in low-cost loans and grants to help small and medium manufacturers test and adopt new production technologies, including digital advances such as robotics and additive manufacturing. Even in a low-interest rate environment, capital is relatively scarce for companies that are too small to tap the bond market.

A somewhat similar initiative to provide loan guarantees for investment in innovative manufacturing technologies, authorized under the America COMPETES Act and supervised by the Commerce Department, never got off the ground because of excessively restrictive terms. Under our proposal, the loans and grants to small and medium companies would be tied to improving the resilience of the manufacturing base.

• Third, the National Resilience Council should sponsor a Manufacturing Regulatory Improvement Commission, along the lines that PPI has suggested in the past. We have no desire to roll back essential environmental and occupational health regulations. But we do want to consider whether rules governing manufacturing have become so restrictive as to unnecessarily force out jobs.

• Fourth, the federal government should take the lead to create a common “language” so that product designers, manufacturers, and suppliers can more easily work together online, just like DARPA helped create the basic structure of the Internet in the late 1960s. Just as a young person can write an app, put it online, and find users around the world, it should be possible to create a design for a new product and easily find potential local manufacturers.

The first two parts of our “National Resilience Council” initiative, which were laid out in our 2019 policy brief, “Jumpstart a New Generation of Manufacturing Entrepreneurs”, find echoes in Joe Biden’s excellent plan for boosting U.S. manufacturing. Key elements that we support include his proposals for bringing back critical supply chains to America, boosting worker training, increasing R&D investment, building up the Manufacturing Extension Partnership, and providing capital for small and medium manufacturers.

Biden’s “Buy America” initiative is understandable, given the stunning size of the trade deficit. But in the long run, improving resilience is more about improving America’s manufacturing capabilities than it is about restricting trade. Globalization and the development of new sources of supply, like India, can be a plus for resilience as long as we keep investing at home.

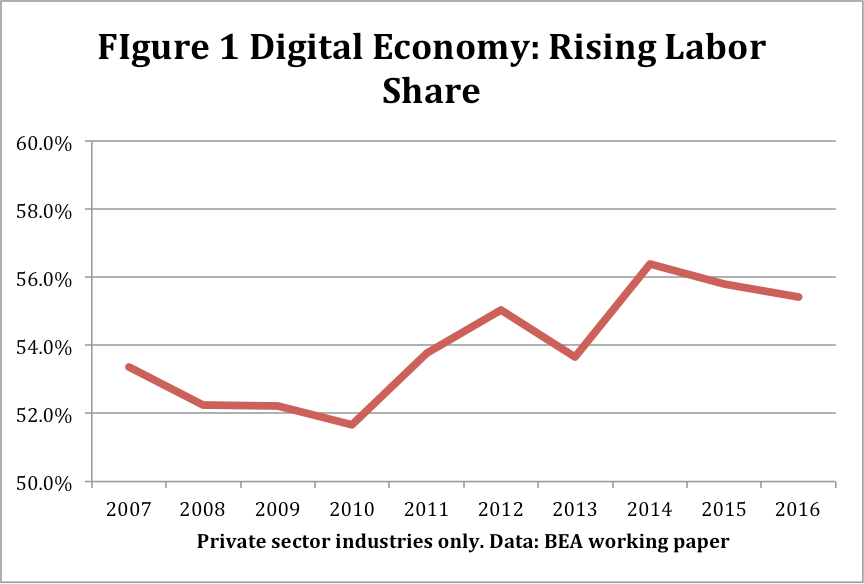

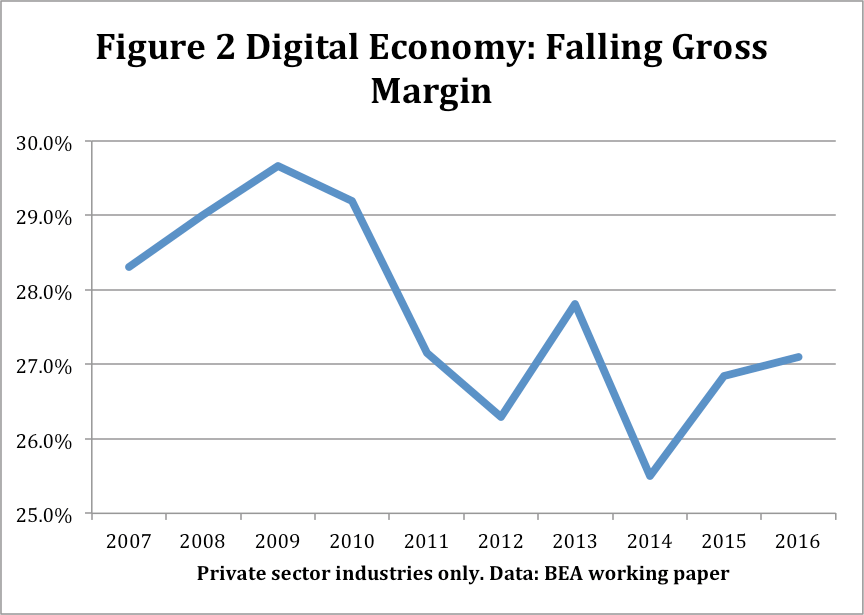

Moreover, one key word is essentially missing from Biden’s plan: Digital. His proposals make no mention of digital manufacturing, cloud computing, 3D printing, or all the other technologies that have the potential to create new business models for America’s factory sector.

The key is connectivity. Twenty-five years ago the rise of the Internet connected computers and made all sorts of new businesses possible, creating millions of jobs. Now it’s time to make even the smallest factory in Ohio or Michigan part of a larger manufacturing network that can compete on a level playing field with larger foreign competitors.

Some manufacturing networks or “platforms”, with names like Xometry and Fictiv, are already starting to sprout. Such platforms can make it easier for buyers to find domestic suppliers who have the necessary capabilities, and then to shift producers quickly when shocks hit or when it becomes necessary to lower carbon emissions. Such platforms can also give manufacturing startups access to immediate markets, make it easier for entrepreneurs to create well-paying factory jobs.

But this transformation of manufacturing is not happening fast enough to help American workers. The government has an important role to play leading the way to the Internet of Goods.