Over the course of the Biden administration, the federal government borrowed more than $5 trillion to pay for programs it did not have the tax revenue to finance. Under current law, the Congressional Budget Office projects these primary deficits — the difference between non-interest spending and tax revenue — to total $7.4 trillion over the next decade.

Financing government spending with deficits is not inherently bad. In fact, it is often necessary to support the economy temporarily during widely recognized emergencies such as wars or recessions. When the crisis subsides, the government can raise taxes or reduce spending to compensate, and the debt is either repaid or at least shrinks as a share of the economy. Debt can also be a useful tool to make investments that will grow our economy over the long-term, such as funding scientific research that lays the foundation for technological progress.

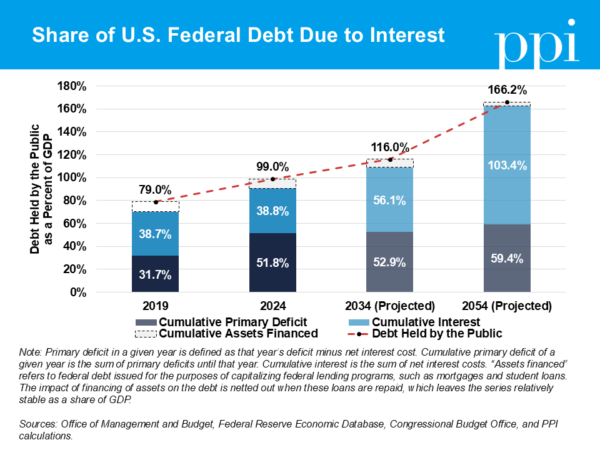

But most federal debt isn’t taken out for these productive purposes. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, more than half of the national debt could be attributed to the cumulative cost of interest payments. This means that most of our debt wasn’t used to finance tangible benefits like providing public goods, uplifting the poor, or subsidizing long-term investments. Instead, it was borrowed just to pay the cost of past debt.

Although it might appear that the share of debt attributable to interest has since shrunk, this is an artifact from the unusual surge of borrowing to finance temporary programs following the COVID-19 pandemic. As the federal government begins paying interest on the debt accumulated over the past four years, and then pays interest on the debt used to pay for future interest payments, cumulative interest payments will snowball to the point where they again make up the majority of debt within the next decade.

The problem will only get worse as time goes on if current law remains unchanged. Over the next 30 years, cumulative interest payments are projected to grow twice as fast as gross domestic product. At the end of that window, the amount of money spent financing past debts will exceed the total value of all goods and services produced by our economy each year.

When we borrow, we are making a transfer from future taxpayers to current ones. By continuing to neglect the long-term cost of debt, we are setting our future selves and subsequent generations for a snowballing debt burden, most of which will not even have been used to buy anything other than time for politicians to procrastinate.

Despite the nation’s deteriorating fiscal health, President-elect Trump and his Republican allies in Congress want to accumulate even more debt. Their top fiscal policy priority for next year — fully extending the expiring provisions of the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act without offsetting the cost — would increase primary deficits by $5.2 trillion over the next 10 years alone. Implementing all of Trump’s proposals from his 2024 presidential campaign, including tax cuts on income from tips, overtime pay, and social security payments, could add as much as $13.5 trillion to primary deficits over the coming decade.

If there is one key takeaway from this analysis, it is that when policymakers pass unfunded tax cuts today, future taxpayers will be stuck with a debt burden that is many times the cost of the tax cuts themselves. When each dollar of debt we undertake is unlikely to be repaid soon, it comes with a far higher cost of interest. This should set the standard for what’s worth borrowing for higher, not lower.