Sterling silver spoons: 3.3%

Stainless steel spoons, ≥25 cents each: 6.8%

Stainless steel spoons, <25 cents each: 14.0%

* About 20% for a spoon valued at 25 cents on imports; 25% for a spoon costing 10 cents or less. Tariff lines are 71141130 for sterling silver, 82159930 for stainless steel spoons costing less than 25 cents each, and 82159935 for spoons at or above 25 cents each.

How is it that cheap spoons are taxed more heavily than sterling silver?

In his 1832 essay on the U.S.’ tariff law, the former Treasury Secretary Albert Gallatin — then a 70-year-old observer and occasional commentator on policy; in earlier life a teenage immigrant from Geneva in the 1780s, a Jeffersonian-Republican politician and founder of the Ways and Means Committee in the 1790s, and Treasury Sec. for the Jefferson and Madison administrations from 1801-1814 — makes a cautious case for progressive taxation:

“Higher duties on luxuries than on articles generally, and in some cases exclusively, used by the less wealthy classes of society are justified by the propriety of laying a heavier burden on those who are the best able to bear it.”

He then glumly notes that, tariffs being an especially opaque way to raise money, and businesses and wealthy people being more able to investigate and complain about their “burdens” than the public in general and the poor in particular, the tariff laws of 1816 and 1828 had done the opposite.

“The principal commodities which have been selected for special protection, iron and all the coarser woollen articles of clothing, are as well as salt, coal, and sugar, essentially necessary to all classes of society. The duties laid on such commodities fall therefore much more heavily, in proportion to their means, on the less wealthy classes; and it has already been seen with what singular ingenuity that on woollens has been so arranged, as to make the poor pay, in every instance, considerably more than the rich. This your memorialists consider to be one of the most obnoxious features of the restrictive system.”

Income and payroll taxes now far exceed the $90 billion tariff system as a U.S. revenue source. But 190 years after Gallatin’s essay, the case of spoons raises some strikingly similar questions. Buyers of cheap stainless steel spoons pay about four times the tax on wealthy neighbors buying sterling, to wit:

(1) Mass-market: Low-priced stainless steel spoons, imported at prices below 25 cents each, get a 14% tariff. For readers familiar with the D.C. metro area, think middle-class and low-income families in Rockville or P.G. County, or the Salvadoran and Ethiopian restaurants along Georgia Avenue just north of the District. No such spoons seem to be made in the U.S. at all.

(2) Luxury: The tariff on sterling silver spoons is 3.3%, a bit less than a quarter of the cheap-stainless rate. Say, McLean and Georgetown, the Mayflower and the Four Seasons, downtown law firms, etc. In this sector, American companies and individuals do make sterling silver spoons, sometimes in batches and sometimes as artisanal pieces, but the prices are high enough to make tariff rates irrelevant.

(3) Mid-tier: More expensive stainless steel falls in the middle, with a 6.8% tariff. One company in upstate New York, Sherill Industries, makes high-priced stainless steel silverware, whose prices seem to average around $4.00 per piece.

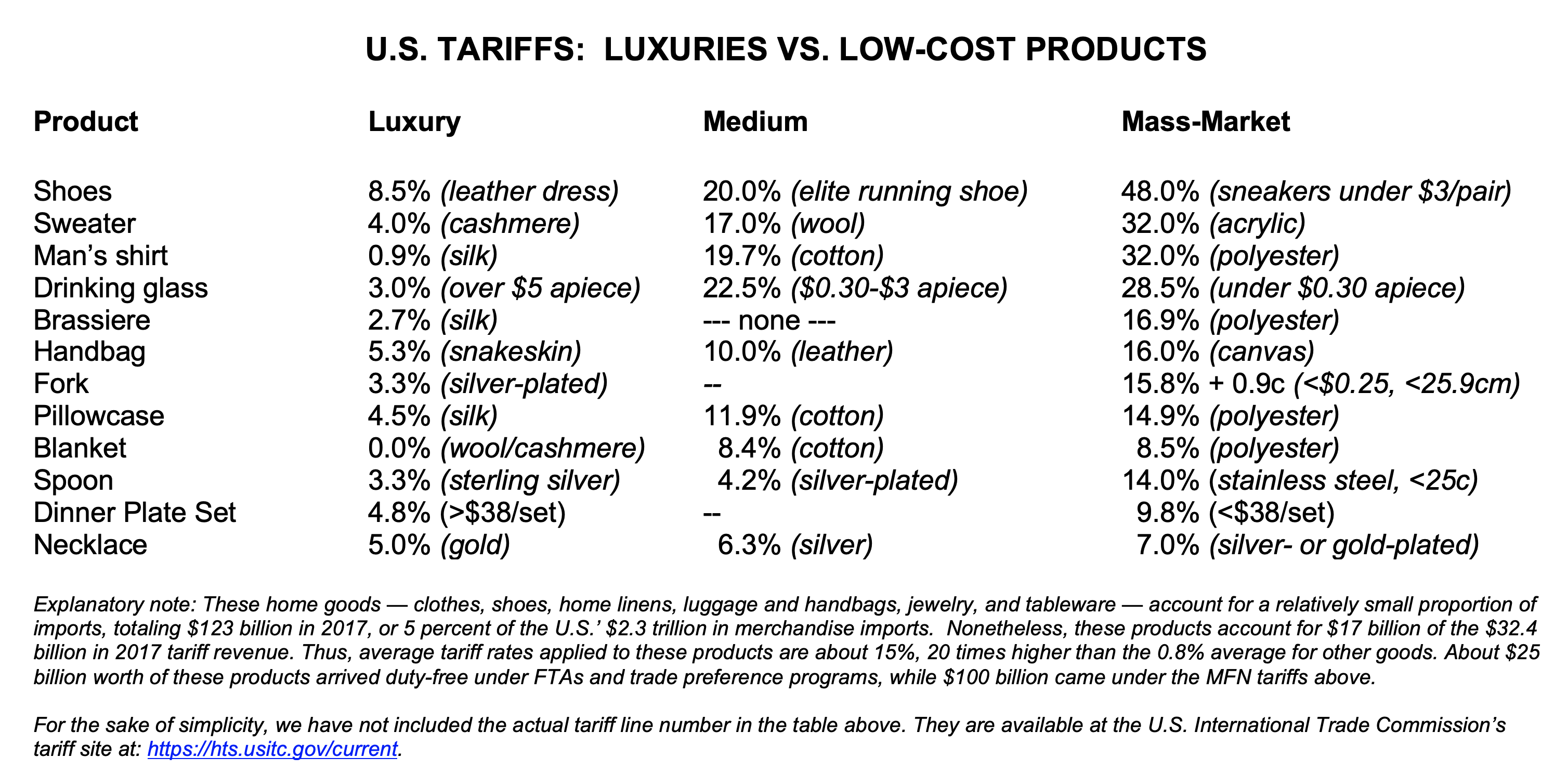

Gallatin’s term “obnoxious” is subjective, but doesn’t seem unreasonable here. Neither the cheap-spoon line (“82159930”) nor the sterling line (71141130”) appear to affect trade flows much, so in this case the tariff system is acting much more in its ‘tax’ role than its ‘trade’ role. There’s little doubt that in this case the poor are taxed considerably more than the rich, and the spoons case is more a typical case than a weird anomaly. An illustrative table of 12 products, drawn from PPI testimony to the International Trade Commission last year:

In this perspective, Gallatin seems to identify a structural challenge that remains powerful despite the passage of nineteen decades. Perhaps especially in tariffs as opposed to more transparent income or sales taxes, low-income people often don’t know when they are being taxed and aren’t in a position to ask for lighter burdens. And in the political system, most tariff analysis relates to trade policy rather than the role of tariffs in taxation; Gallatin’s Ways and Means Committee, in fact, appears not to have held a hearing on the tax implications of tariff policy since 1974. So with little knowledge about strange phenomena like the differential rates on stainless steel and sterling even among policymakers, policies rarely get critical examination and “the less wealthy classes” seem to wind up carrying the heavier burdens.

Analysis then and now:

Frederick Taussig’s State Papers and Speeches on the Tariff collection (1892), featuring Gallatin’s 1832 essay along with other 18th- and 19th-century trade policy luminaries (Alexander Hamilton, Daniel Webster, and the now-obscure Robert Walker, who was James K. Polk’s Treasury Secretary in the 1840s).

Economists Miguel Acosta and Lydia Cox trace the low-tariffs/luxury vs. high-tariff/mass-market skew of the U.S. tariff system back to agreements of the 1930s and 1940s.

PPI’s Ed Gresser looks at consumer goods tariff inequities in 2022 testimony to the International Trade Commission.

Tariff schedule:

The Harmonized Tariff Schedule; see Chapter 71, heading 7114 for sterling silver and other precious-metal “silverware,” and Chapter 81, heading 8215 for “base metal.”

And a summary of the 11,414 current U.S. tariff lines – how many “duty-free,” how many covered by tariffs, how many the various Free Trade Agreements waive.

And via the St. Louis Fed, a copy of the 1828 tariff law which so annoyed ex-Secretary Gallatin.

More on Gallatin:

The Treasury Department’s Albert Gallatin statue.

Nicholas Dungan’s admiring 2010 bio.

And a silverware-maker:

Ed Gresser is Vice President and Director for Trade and Global Markets at PPI.

Ed returns to PPI after working for the think tank from 2001-2011. He most recently served as the Assistant U.S. Trade Representative for Trade Policy and Economics at the Office of the United States Trade Representative (USTR). In this position, he led USTR’s economic research unit from 2015-2021, and chaired the 21-agency Trade Policy Staff Committee.

Ed began his career on Capitol Hill before serving USTR as Policy Advisor to USTR Charlene Barshefsky from 1998 to 2001. He then led PPI’s Trade and Global Markets Project from 2001 to 2011. After PPI, he co-founded and directed the independent think tank Progressive Economy until rejoining USTR in 2015. In 2013, the Washington International Trade Association presented him with its Lighthouse Award, awarded annually to an individual or group for significant contributions to trade policy.

Ed is the author of Freedom from Want: American Liberalism and the Global Economy (2007). He has published in a variety of journals and newspapers, and his research has been cited by leading academics and international organizations including the WTO, World Bank, and International Monetary Fund. He is a graduate of Stanford University and holds a Master’s Degree in International Affairs from Columbia Universities and a certificate from the Averell Harriman Institute for Advanced Study of the Soviet Union.

Read the full email and sign up for the Trade Fact of the Week