By Ben Ritz

A column in the Wall Street Journal last week by House Budget Committee Chairman Jodey Arrington (R-Texas) and former Senator Phil Gramm (R-Texas), titled “Welfare is What’s Eating the Budget,” argued that “means-tested programs, not Medicare and Social Security, are behind today’s massive debt.” And it’s profoundly wrong.

To make their argument, Arrington and Gramm rely upon a measure called “unobligated general revenue,” which they define as “total revenue net of Medicare and Social Security payroll taxes and premiums and mandatory interest on the public debt.” They argue that means-tested “welfare” programs – those that provide benefits only to people below a certain income threshold – claim a higher share of this revenue than Medicare and Social Security, making them the bigger fiscal challenge facing the federal government. Even if this metric were the appropriate one for comparison (and I’ll explain why it isn’t), it wouldn’t support the assertion that welfare is a bigger contributor to today’s budget deficits than Medicare and Social Security.

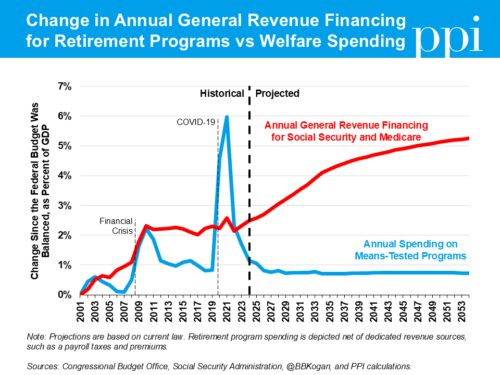

The chart below shows the change in total spending on means-tested programs and general revenue used to cover the gap between dedicated revenue and spending on Medicare and Social Security benefits each year since 2001 – the last year in which the federal budget was balanced. In almost every year, the increase in annual welfare spending relative to 2001 levels was less than or equal to 1% of gross domestic product (GDP). The only exceptions were the years following the 2008 financial crisis and COVID-19 pandemic, both of which were times in which unemployment sharply increased and so more people fell into the social safety net. By comparison, the same measurement for general revenue used to pay for Medicare and Social Security was roughly twice that amount in every one of the last 15 years.