The new reports released yesterday by the trustees for Social Security and Medicare warn that both programs face a growing gap between scheduled benefits and the dedicated revenue sources that finance them. If nothing is done to address the shortfalls in these programs, they will pose a grave threat to both the beneficiaries who depend on Social Security and Medicare and the other critical public investments that will increasingly have to compete with these programs for limited resources.

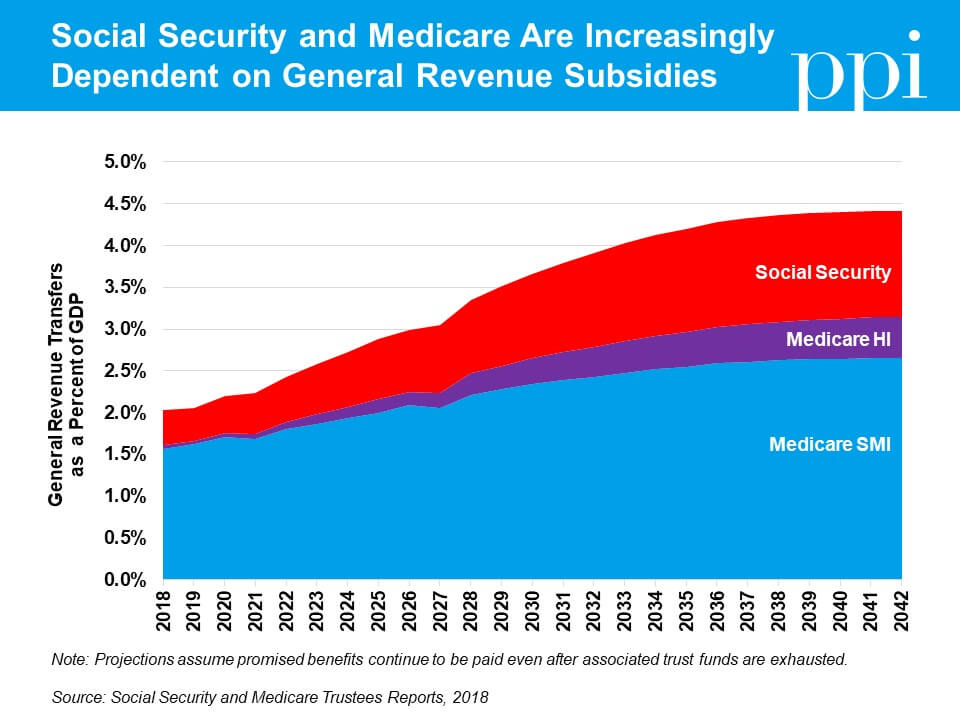

Unlike most programs in the federal budget, which are funded from the same pool of general revenues, Social Security and Medicare were designed with dedicated revenue sources intended to finance their benefits (primarily payroll taxes for Social Security and a combination of taxes, premiums, and fees for Medicare). But in 2017, Medicare required $307 billion in general revenue funding to meet its obligations, while Social Security required another $41 billion – a combined gap which equaled roughly two percent of gross domestic product.

In less than 20 years, that gap will double to more than four percent of GDP as the baby boomers move into retirement and the ratio of workers to beneficiaries falls. This growth places an enormous burden on the rest of the federal budget by increasing existing deficits and creating competition with all the other federal programs, from defense to education, that require general revenue funding. For comparison, discretionary spending – the part of the budget that includes all federal spending appropriated annually by Congress, including everything from the military to infrastructure funding – totaled just 6.3 percent of GDP in 2017 and is set to fall in future years.

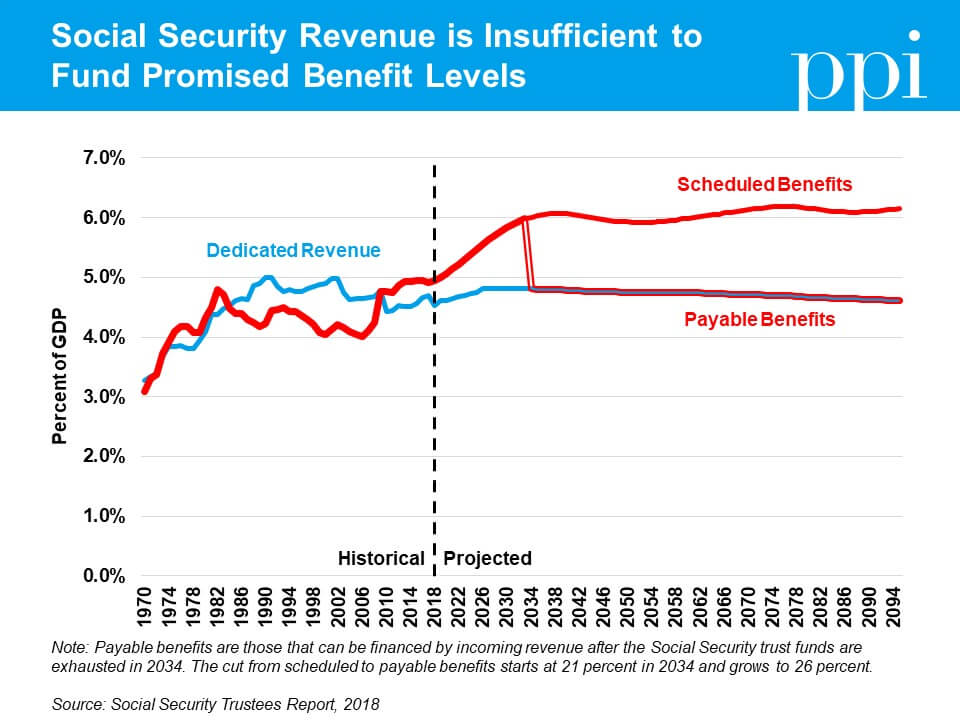

Under current law, Social Security and Medicare are allowed to spend more than they collect in dedicated revenue, but only up to a point. In years when dedicated revenue exceeds spending, the Treasury Department credits one of four trust funds for the balance: the Old Age and Survivors Insurance (OASI) and Disability Insurance (DI) trust funds for Social Security, and the Hospital Insurance (HI) and Supplemental Medical Insurance (SMI) trust funds for Medicare. In subsequent years when spending exceeds revenue, Social Security and Medicare can then use transfers from general revenue to draw upon these established surpluses and make up their annual shortfall.

Once the fund balances are exhausted, however, benefits are automatically reduced to what is payable with incoming revenue (except for SMI, which by design is partially funded with general revenues and can never be exhausted). The trustees projected the following trust fund exhaustions in their reports:

Waiting until the last minute to address these shortfalls would be catastrophic for a number of reasons. First, it creates the prospect of sudden and draconian benefit cuts for seniors and individuals with disabilities. Uncertainty about the future of Social Security and Medicare undermines the ability of all Americans to plan for their retirement accordingly and risks jeopardizing public support for the program. In fact, recent polls have found a majority of Americans both young and old already lack confidence in the ability of Social Security and Medicare to pay future benefits as scheduled. Restoring long-term solvency to these programs would help restore public confidence in them as well.

The alternative to sudden benefit cuts, that future workers will be asked to bear the entire cost of poor decisions made by previous generations, is hardly better. The Social Security trustees note in their report that if action were delayed until 2034, policymakers would need to immediately and permanently increase revenue by an amount equal to a one-third increase in the payroll tax rate to prevent sudden benefit cuts in Social Security alone. Combined with the even-larger tax increases necessary to fully fund Medicare, this would be an enormous tax burden to place entirely on the shoulders of tomorrow’s workers. The longer policymakers wait to begin phasing in changes, the harder it will be to have older generations contribute to the solution and defray the burden.

Finally, the competition for limited resources created by growing general revenue subsidies threatens to crowd out other important progressive priorities. General revenue is already insufficient to cover current spending levels – a reality that pre-dated last year’s tax legislation. Because the trust funds aren’t invested as external savings, the government must borrow from private investors to repay the trust fund surpluses as they’re drawn down (replacing this intragovernmental debt with more economically significant debt held by the public). This debt comes with added interest costs, further increasing the pressure on the federal budget.

In the coming years before trust fund exhaustion, funding that could be used for public investments in our future such as infrastructure, education, and scientific research will be increasingly consumed by growing subsidies for social insurance programs and interest costs. Even worse would be a scenario in which policymakers use the existence of the trust funds as an excuse to delay action on correcting the imbalances between dedicated revenues and spending, only to abandon the system and provide unlimited infusions of general revenues when the trust funds’ exhaustion would otherwise force hard choices.

We can do better. Our elected officials should table costly policy proposals that threaten to make the problem worse and instead work towards phasing in pragmatic reforms to strengthen and secure the future of these important programs.