As millions of Americans rush to file their tax returns, former Senator Bob Kerrey joined the Center for New Liberalism and the Progressive Policy Institute’s Paul Weinstein and Alec Stapp to discuss whether or not the US government should adopt return-free filing for individual taxes. The participants discussed the costs and benefits of return-free filing relative to our current voluntary tax filing system, the main problems with our current tax system, and whether or not return-free filing would reduce tax evasion.

Category: Uncategorized

FICO rolls out new credit scoring model

Consumers are getting turned down for all sorts of financial products, from personal and auto loans to credit cards. The Wall Street Journal, using Equifax data, reports that credit card approvals totaled 483,000 in the week ending May 10, down from 856,000 in the week ending March 22. To compare to the year prior, weekly card approvals in 2019 “rarely fell below 1.2 million,” according to The Wall Street Journal.

But as banks are tightening their lending requirements, a new tool is trying to prevent lenders from cutting off consumers’ access to credit.

Fair Isaac Corp., the data analytics company behind the FICO credit score, has just launched the FICO Resilience Index, a new scoring model designed to help lenders better assess consumers’ sensitivity to financial stress by looking at their capacity to survive financially though a downturn.

“The FICO Resilience Index, used in conjunction with a FICO Score, allows card issuers to limit access less than they otherwise would have because they can now identify borrowers who are more resilient to the economic downturn,” Sally Taylor, VP of FICO Scores, tells CNBC Select.

FICO defines resilient borrowers as “consumers that are more likely to pay as agreed in the event of a recession.”

The new scoring model ranks consumers’ resiliency on a scale of 1 to 99. The higher your score, the higher the risk you will default on your payments; the lower your score, the more likely you are to make on-time payments even when the economy experiences a downturn.

Read the full piece here.

This piece was originally published on CNBC by Elizabeth Gravier on June 29, 2020.

Economic Impacts of a Moratorium on Consumer Credit Reporting

Two bills introduced in Congress, H.R. 6370 and S. 3508, ‘‘Disaster Protection for Workers’ Credit Act of 2020’’ would impose a moratorium on credit reporting of “adverse information” for the duration of the coronavirus crisis. Credit scores are an integral part of the consumer credit underwriting process as their power to predict the likelihood of borrower default is well-established empirically. Consequently, lenders have come to heavily rely on the integrity and information content of credit scores as a critical measure of a borrower’s creditworthiness.

Economic theory suggests that in the absence of viable mechanisms to effectively distinguish between high and low risk borrowers, lenders will ration credit. Under a credit reporting moratorium, the reliability of credit scores to distinguish between borrower risks would come into question. Lenders would respond to the proposed credit reporting moratorium by raising minimum credit score requirements and/or raising borrowing rates as a credit uncertainty premium to offset the risk they face from the moratorium. During the 2008 financial crisis, lenders raised credit score minimums on FHA loans, for example, beyond those set by the agency as a response to uncertainty over indemnification provisions that posed significant costs to lenders. And today, during the coronavirus, a number of Ginnie Mae originators have raised credit scores to blunt some of the risk they face due to requirements to pass-through mortgage payments to investors, including those in default or subject to forbearance.

Read the full piece here.

This piece was originally published on Chesapeake Risk Advisors, LLC by Clifford Rossi on June 17, 2020.

WEBINAR: What Worked: Remote Instruction During COVID-19

When America’s schools abruptly closed in March, few had strategies for keeping students engaged. Watch RAS Associate Director Tressa Pankovits, as she moderated a 90-minute interactive discussion with CRPE and Public Impact analysts who co-presented comprehensive new data on how school systems performed, and top educators shared how their teams excelled under pressure.

Panelists include:

Bree Dusseault, Practitioner-in-residence at the Center on Reinventing Public Education

Lyria Boast, Vice president for data analytics and a senior consulting manager at Public Impact

Joyanna Smith, DC Regional Director at Rocketship Public Schools

Amy D’Angelo, Regional Superintendent, Achievement First Charter Schools

Brian Riddick, Principal at Butler College Prep, of Noble Network of Charter Schools

Moderator: Tressa Pankovits, Associate Director, Reinventing America’s Schools Project

Our educator panelists described their fast pivot from the classroom to the cloud, and they shared their strategies for ensuring distance learning was effective, including setting high expectations and relentless student engagement. They dissected lessons learned, and examined pitfalls to avoid in the coming school year.

Watch here.

PPI Statement on the FDA’s Modified Risk Assessment of IQOs

PPI strongly supports science-based regulatory policy, no matter where the evidence leads us. This means tackling tough problems with an open and pragmatic mind to achieve the best possible outcomes. Moreover, we place a high premium on clear communication of information relevant for public health, especially in today’s turbulent times.

From that perspective, we applaud the FDA’s authorization of “the marketing of Philip Morris Products S.A.’s “IQOS Tobacco Heating System” as modified risk tobacco products (MRTPs).”

These are the first tobacco products to receive what the FDA calls an “exposure modification order.” That permits “the marketing of a product as containing a reduced level of or presenting a reduced exposure to a substance or as being free of a substance when the issuance of the order is expected to benefit the health of the population.”

In other words, the FDA specified precise language that the manufacturer could use, including that “switching completely from conventional cigarettes to the IQOS system significantly reduces your body’s exposure to harmful or potentially harmful chemicals.” And that’s a good thing!

The Uneven Distribution of Pain: Healing the Broken Labor Market

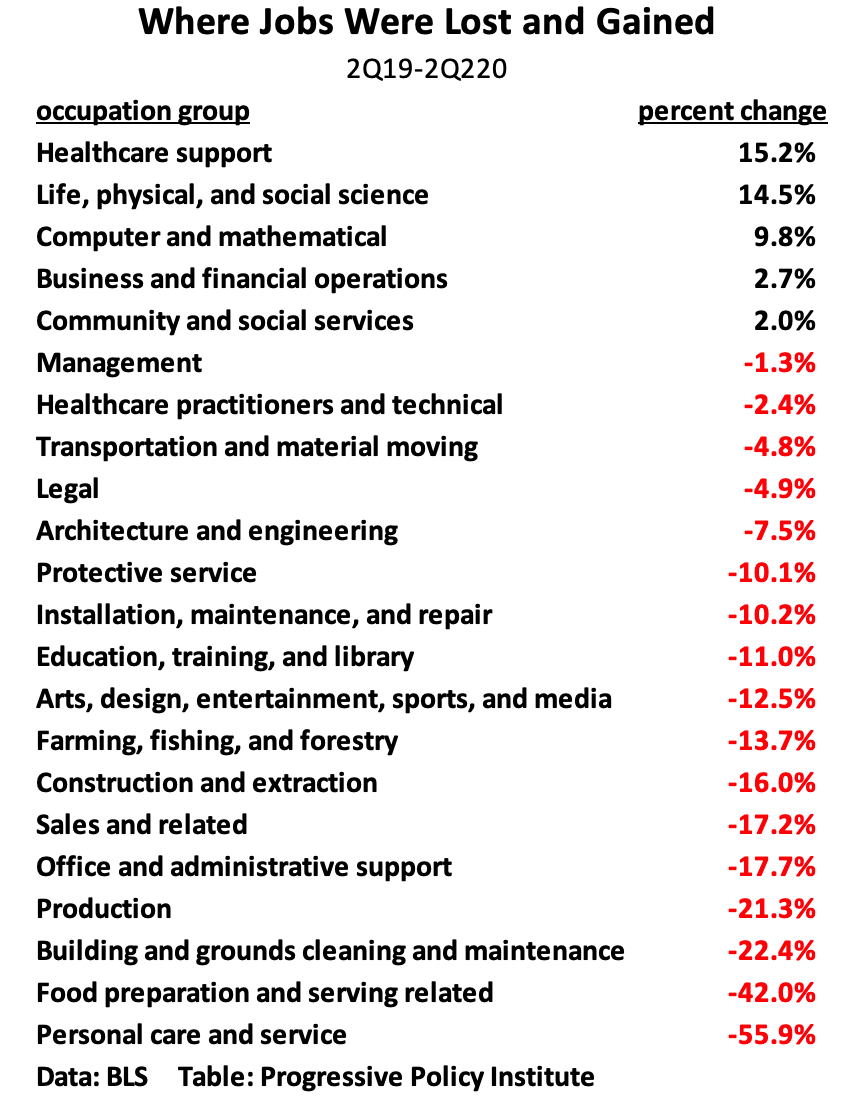

The Covid recession is the most uneven economic downturn in history. Take a look at the following table, which we calculated from last Thursday’s employment data.

The table compares occupational employment in the second quarter of 2020 with the second quarter of 2019. On the one hand, some occupations, like computer and mathematics-related jobs, have seen a significant employment gain over the past year of almost 10%. On the other hand, food preparation and personal care jobs saw an almost inconceivable plunge in excess of 40%. Production jobs are down more than 20%.

This differential frames the economic task ahead. How can we make sure that these workers, detached from the labor force, can find new jobs quickly when the economy starts to recover? Moreover, many of the businesses where they were formerly employed are likely to have disappeared as the country continues to stagger under the pandemic.

PPI has identified several policy prescriptions that can help. Just to summarize here:

First, policymakers must make it easier for the small businesses that survive to quickly expand to fill the void, especially in the hard-hit restaurant and personal care industries. Elliott Long describes how adopting a “startup tax credit” can help encourage small businesses to grow. Designed like the earned income tax credit, but only for businesses, the startup tax credit helps give small companies a boost in the right direction. In addition, state and local governments need to be wary of regulations that make it harder for companies to expand.

Second, the U.S. has to adopt policies to encourage shorter supply chains and manufacturing entrepreneurship, It should be a national imperative to help small manufacturers adopt digital technologies that make them more flexible and able to compete with foreign suppliers, and then connect them up with larger buyers.

Third, any economic recovery and infrastructure legislation should include large investments in clean manufacturing, as Paul Bledsoe of PPI has advocated in a recent report. That means many more production and construction jobs building electric vehicles, charging stations and other elements of green technology, while upgrading all of our essential infrastructure.

Fourth, digital technologies can help connect up workers with open jobs much faster. We’ll be writing more about that soon.

The UK Online Ad Market

Last year I did a paper entitled The Declining Cost of Advertising: Policy Implications. Not surprisingly, I was intrigued by the new report from the Competition and Markets Authority in the UK, entitled Online platforms and digital advertising market study . I’m still going through the report, which exceeds 400 pages, not including multiple appendixes.

But I just want to highlight one important point. The report repeatedly alludes to the impact of advertising on consumer prices for goods and services. For example:

The costs of digital advertising, which amount to around £14 billion in the UK in 2019, or £500 per household, are reflected in the prices of goods and services across the economy. These costs are likely to be higher than they would be in a more competitive market, and this will be felt in the prices that consumers pay for hotels, flights, consumer electronics, books, insurance and many other products that make heavy use of digital advertising.

But here’s the thing—ad spend in the UK, measured as a share of UK GDP, is more or less flat over the past thirty years (chart below). There’s no evidence that the burden on advertisers or consumers has increased because of the arrival of Google and Facebook to the UK ad market. Indeed, it may have gone down a bit, comparing the 1.1% peak in 2019 with the 1.2% peak in 2000, before Facebook existed and when Google advertising was first getting started.

Given how many places ads appear these days, it’s reasonable that advertising in the UK has become much more intensive over time–that is, in real units advertising has grown faster than overall real UK GDP. If so, then the shift to digital advertising has coincided with a fall in the price of advertising relative to other UK goods and services. The easiest interpretation, at least for me, is that advertisers are consistently getting a bigger bang for their buck from digital advertising, without paying more in total.

A Transatlantic Digital Trade Agenda for the Next Administration

CAN A NEW DEMOCRATIC ADMINISTRATION RECONSTRUCT DIGITAL TRADE POLICY WITH EUROPE FROM THE ASHES OF TTIP?

As the global leader in digital trade, the United States has a big stake in ensuring that international rules facilitating its continued expansion are put in place.

The Obama Administration’s bold agenda to establish these rules across Europe and the Asia-Pacific did not yield lasting success, with the failure of the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) negotiations and the Trump Administration’s withdrawal from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). Nonetheless, the key elements of US digital trade policy enjoy bipartisan policy support, providing a promising basis for the next Democratic administration to re-engage with Europe, our biggest digital trading partner.

Part 1 of this issue brief explains why international rules are needed to protect and facilitate digital trade. Part 2 describes the turbulent past decade in transatlantic trade relations and the growing importance of US digital trade with Europe. Part 3 explains why the US government and the European Union (EU), during TTIP negotiations, were unable to agree on a digital trade chapter, including a key provision guaranteeing the free flow of data. Finally, Part 4 suggests how two parallel sets of trade negotiations beginning early this year — between the EU and the United Kingdom (UK) and between the United States and the UK — may help a future US Administration end the transatlantic stand-off over digital trade.

1. THE CASE FOR DIGITAL TRADE AGREEMENTS

The United States leads the world in the fast-growing digital economy.1 Digital services include not just information and communications technology (ICT) but also other services which can be delivered remotely over ICT networks (e.g. engineering, software, design and finance).2 Although trade in digital services is hard to measure precisely, there is no mistaking that it has become one of the fastest-growing areas for the United States internationally. In 2017, all types of digital services made up 55% of all U.S. services exports, and yielded 68% of the U.S. global surplus in services trade.3 The beneficiaries of this burgeoning area of trade are not just the U.S. technology giants, but also many smaller and medium-sized companies that develop and sell digital services or use ICT networks for marketing products to consumers.

More than a decade ago, the Office of the US Trade Representative (USTR) recognized the US comparative advantage in digital services trade and began to pursue binding rules with a number of foreign governments. TPP negotiations were the first major step in this direction. The TPP agreement signed by the Obama Administration included provisions designed to protect against practices harmful to digital trade. It prohibited:

- Customs duties and other discriminatory measures on digital products like e-books, movies, software and games;

- Requirements that data or computing facilities be localized in the foreign jurisdiction;

- Discriminatory treatment of crossborder data flows;

- Obligations to use local technology, content, or suppliers;

- Discriminatory foreign standards or burdensome testing requirements; and

- Requirements for disclosing source code and algorithms.

TPP also included facilitative measures:

- Requiring governments to adopt measures to protect against on-line fraud and guard consumers’ personal information;

- Promoting cooperative approaches to cybersecurity; and

- Facilitating the use of electronic authorizations and signatures for e-commerce, electronic payments, and other on-line applications

President Trump’s decision to withdraw the United States from TPP left US digital services companies exposed to these harmful practices in the Asia-Pacific region. From the perspective of liberalizing and expanding US digital trade, it was a spectacular own goal.4 However, USTR quickly set out to partially mitigate its effect by seeking bilateral trade accords with some TPP signatories. Digital chapters in the updated Korea-US Free Trade Agreement (KORUS), the new US-Mexico-Canada Free Trade Agreement (USMCA), and, most recently, the Japan-US Digital Trade Agreement largely duplicate the TPP’s digital trade provisions.

2. THE TRANSATLANTIC TERRIBLE TEENS

Transatlantic trade politics also has seen its share of drama over the past decade. The comprehensive TTIP negotiations begun in 2013 badly backfired. Popular fears of US corporate domination flared across Europe, the EU’s member states failed to back the project enthusiastically, and progress between US and European Commission negotiators on the many subject-matter chapters proved glacial. As the Obama Administration came to an end, TTIP talks were quietly shelved.

The Trump Administration’s trade agenda for Europe has been strikingly different. It has concentrated on rectifying the sizeable US deficit in merchandise trade with the EU, which reached an estimated record high of $168 billion in 2018.5 The President demanded that the EU, which is solely responsible for the bloc’s international trade relations, address the imbalance in such areas as steel, aluminum and automobile trade. (He also somewhat mystified Germany by insisting that it negotiate directly with the United States to reduce the U.S. goods trade deficit.) The US Government determined that a number of jurisdictions including the EU had engaged in trade practices unfair to US steel and aluminum, and imposed higher tariffs on these imported products as a consequence; higher tariffs on European autos so far remain a threat.

In the summer of 2018, European Commission (then-)President Jean-Claude Juncker managed partly to defuse transatlantic tensions by agreeing to negotiate with the United States on increasing EU purchases of US-made industrial goods and on related regulatory standard.

Juncker also committed to greater European purchases of US natural gas and soybeans. Trump in return agreed not to proceed with unilateral tariff increases for the time being. Since the advent of new EU leadership late last year, USTR Robert Lighthizer and his Commission counterpart Philip Hogan have stepped up efforts toward reaching, before the 2020 US presidential election, a limited accord in the areas identified by Trump and Juncker.

Throughout the decade, the volume of goods and services trade across the Atlantic has continued to grow steadily. The United States and the European Union are still each other’s largest trading partners. US goods exports to the EU grew to $293 billion in the first eleven months of 2018, a 13% increase over the previous year.6 US exports of all types of services to the EU reached a record $298 billion in 2017, resulting in a $66 billion surplus in 2017.7 European countries comprise four of the top ten export markets for US services, and in 2017 the Union as a whole absorbed 37% of US services exports.8

Despite the continuing growth in trade, the next Democratic administration will inherit a transatlantic trade policy environment characterized by an unusually high level of tension and distrust. TTIP’s failure appears to have stifled any impulses in Washington and Brussels simply to resume the slog towards a comprehensive trade agreement. Still, there are good reasons for Democrats to not abandon the work begun on digital trade during the TTIP negotiations.

3. THE US DIGITAL TRADE IMPASSE WITH EUROPE

Since Trump’s trade ambitions with the EU remain firmly focused on the goods deficit, the question of whether the United States should resume direct digital services trade negotiating efforts with Europe seems likely to be deferred till the next administration. From an economic perspective, the case for US re-engagement is compelling. In 2017, the United States exported $204.2 billion in digital services to Europe, generating a surplus in this area of more than $80 billion.9 International data flows, measured in terms of capacity for data bandwidth, also are heavily skewed in a transatlantic direction. Cross-border data transfers between the United States and Europe, by this measure, are 50% higher than those between the United States and Asia.10 In sum, the transatlantic area is the world’s largest for digital trade.

During TTIP negotiations, the United States proposed language close to TPP digital trade provisions, but the EU objected to a number of them. One of the most important was a US proposal to guarantee cross-border ‘free flow’ of electronic information for business purposes, and to put bounds on the extent to which European public policy measures relating to personal privacy could serve as an exception to unrestricted data flows.

The United States proposed that public policy exceptions be allowed, but that they be subjected to long-established World Trade Organization (WTO) disciplines. These WTO rules allow for exceptions for legitimate public policy objectives, so long as they do not constitute arbitrary or unjustifiable discrimination or disguised restrictions on trade, and they are narrowly tailored to achieve a public policy objective.11 Alleged breaches could ultimately be addressed through a formal dispute settlement system, if necessary.

The EU regarded the US proposal as an attack upon its unfettered discretion to apply its privacy laws to data moving across the Atlantic, and it rejected the possibility of any discipline based upon WTO rules. The EU’s rejection of objective limits on its potential public policy measures leaves it free to invoke privacy rules as a basis to discriminate against US digital service providers or to protect local competitors. The issue remained firmly deadlocked when TTIP negotiations were set aside.12 Since then, the United States and the EU have not re-engaged bilaterally on digital trade rules.

Both governments are among the eighty countries participating in a low-profile multilateral negotiation on electronic commerce (e-commerce) launched a year ago under WTO auspices, however.13 In Geneva, the United States has tabled a similar proposal to its TTIP and TPP language; the EU so far has not managed to offer a counter-proposal. For the time being, it seems unlikely that the WTO negotiations will yield quick success in settling the disagreement between the EU and the United States and other like-minded countries on regulatory limits to the free flow of data.14

A new Democratic Administration should engage bilaterally with the EU to see if there might be scope for a targeted digital trade agreement, but without softening its insistence on a rigorous free flow of data obligation. Agreeing with the EU on the proper scope for public policy exceptions should not be an impossible task, as WTO rules provide a useful framework. Moreover, it is conceivable that the new leadership of the European Commission at some point will consider jettisoning its insistence on a selfjudging privacy exception, in favor of language more consistent with international trade law.

4. BREXIT AND DIGITAL TRADE

Following Britain’s January 31 departure from the European Union, it now has embarked on the urgent task of negotiating its future economic relationship with the EU. Brexit notwithstanding, the EU will remain the UK’s principal trading partner; 45% of overall UK exports in 2018 were destined for the Continent.15 At the end of 2020, however, if no accord is reached, EU tariffs and quotas on UK exports would revert to much higher WTO tariff levels, which would have a damaging effect on UK-EU trade.

In addition to fixing tariff levels, Britain and the UK also must agree on the extent to which the UK will continue to adhere to EU regulations in a host of areas – for example, workers’ and consumers’ right, the environment, and antitrust. Many observers expect the UK-EU talks on these non-tariff barriers to be difficult and drawn out, likely stretching beyond the 2020 deadline. Despite continuing tough UK rhetoric, the parties may well settle for a ‘phase one’ agreement on goods tariffs, and grant themselves an extension into 2021 or beyond to complete the rest of a comprehensive agreement.

Setting the terms for digital trade with the EU will be particularly important for Britain. UK services exports to the EU yielded a £77 billion surplus in 2018, more than offsetting a deficit in goods trade.16 Approximately three-quarters of Britain’s data flows are with EU countries17, making harmonization with the Continent on privacy regulation crucial for its thriving data-dependent businesses, such as financial services.

In its negotiating mandate for the future economic partnership agreement with the UK, the EU specifically calls for provisions facilitating digital trade, but also indicates an intention to “address data flows subject to exceptions for legitimate public policy objectives, while not affecting the Union’s personal data protection rules.”18 The UK’s counterpart negotiating mandate similarly calls for measures to facilitate the flow of data to and from the EU, and expresses an ambition to go beyond the digital trade provisions in the EU’s trade agreements with other countries.19

The Union previously had pledged to decide before the end of 2020 whether the UK’s postBrexit privacy protections are ‘adequate’ in relation to those on the continent; an adequacy determination would be by far the most favorable and efficient legal basis for data flows across the Channel.20 The EU should have leverage in this separate negotiation, and as a result the UK’s future data protection regime should remain generally close to the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). An adequacy finding is not a foregone conclusion, however, as Britain may be reluctant to alter its wide-ranging surveillance laws.21

The United States is also a very important trading partner for the United Kingdom, accounting for 15% of Britain’s total trade.22 Nearly a fifth of Britain’s exports head across the Atlantic, more than double the share it sends to Germany, its next-biggest trading partner.23 US services trade with the United Kingdom exceeds goods trade, and is growing; US services exports measured $74.1 billion in 2018, generating a surplus of $13.3 billion that year with Britain.24 There are more transatlantic undersea cable connections transmitting data directly between the United States and the United Kingdom than with the rest of Europe combined.25 Foreign affiliates of U.S. multinationals supply more information services in the United Kingdom than in any other European country.26

The Office of the US Trade Representative and the UK Department for International Trade started negotiations on a bilateral trade agreement in May. The United States seeks a comprehensive agreement with the British, including a chapter on digital trade in goods and services and cross-border data flows modeled on the most recent U.S. bilateral successes with other countries.27 The United Kingdom’s negotiating objectives with the United States are broadly consistent with the United States perspective on digital trade.28 They specifically mention the importance of preserving UK data protection rules in an agreement with the United States.29 The United States officially attaches the highest priority to these negotiations and aims to complete them in 2020.30 Privately, US officials acknowledge that the United Kingdom will have to give greater priority this year to redefining its all-important trading relationship with the EU, before US-UK talks can advance definitively.

The most that US and UK trade negotiators may be able to deliver this year is a partial agreement setting tariffs and quotas for goods. A new Democratic administration would be well-advised to build upon whatever progress is achieved with the UK this year, and to give particular priority in the future to agreement on digital trade. The latter could even take the form of a stand-alone agreement on digital trade, as was done in the Japan – United States Digital Trade Agreement, if a comprehensive US-UK trade agreement proves a longer-term prospect.

The United States and the United Kingdom should be able to make rapid progress on many aspects of a digital trade agreement. Historically, both governments have shared a philosophical commitment to open international trading regimes. Both have highly developed digital economies and leading-edge digital services companies. Each favor free data flows and opposes data localization measures. Intangible factors including similar legal traditions also could speed talks.

The long arm of the European Union will constrain the United Kingdom’s negotiating room on digital trade with the United States, however. The EU may insist that, as part of the price for adequacy, the UK agree not to undermine the Union’s position on data flows in any of the UK’s future trade agreements with third countries. The United States, for its part, presumably would take the same position on this issue as it took in TTIP – that legitimate privacy measures are those permitted under WTO principles rather than by EU fiat.

Still, in the short term, the United States may be better off tackling this tough issue with the United Kingdom than seeking to resolve it bilaterally with the EU. The British are in a tough negotiating position: they must find a way forward on data flows with both the EU and a range of important third country trading partners. UK negotiators will need all their creative legal talents to find a way through this intersection of digital trade and privacy law. If they succeed, the payoff in a settled legal landscape for digital trade across both the Channel and the Atlantic eventually could be substantial. Brexit has generated considerable trade uncertainty, but it also ultimately could yield dividends for digital trade.

Scoring a Better Future — Getting Facts on Credit Scores & How They Work

Join Paul Weinstein, Jr., Senior Fellow at the Progressive Policy Institute in Washington, D.C., and Joanne Gaskin, Vice President of Scores and Analytics at FICO, for a discussion on the changes FICO has made to its models, and how they may impact credit scores, particularly for millennials and GenZ.

Privacy Wars: Peril and Promise for Transatlantic Data Transfers

Authored by Ken Propp, Professor of European Union Law, Georgetown University Law Center; Senior Fellow, Atlantic Council; PPI Fellow

In May 2013, Edward Snowden publicly disclosed a trove of highly-classified information about US signals intelligence programs around the world, unleashing a torrent of outrage both in the United States and abroad. Nowhere did his revelations have a bigger impact than in Europe, where the extent of activities conducted by the US National Security Agency, sometimes with the cooperation of foreign intelligence services, came as a huge shock.

European Union officials were chagrined — and a little flattered — to learn that internal conversations with their overseas delegations had been intercepted. German headlines trumpeted the alleged tapping of Angela Merkel’s personal cellphone. Snowden’s revelations sharply disrupted the generally cooperative character of US-EU relations. “It seemed that the entire well of US-EU relations had been poisoned by the fallout from the Snowden affair,” the US Ambassador to the European Union during the period has written, citing its political impact on negotiations over a potential transatlantic free trade agreement, among other effects.

In Brussels, the evident scale of NSA surveillance was perceived as a challenge to ‘data protection’, the extensive body of privacy law that is one of the EU’s signature regulatory initiatives. Snowden’s disclosures provoked an almost existential crisis in Europe about whether privacy protection even mattered. Not long after, European privacy activists went to court to challenge the legitimacy of data transfers to the United States, in a series of cases that rumble on to this day. Their efforts have upended one US-EU data transfer agreement, the Safe Harbor Framework, and now threaten to do the same for the successor Privacy Shield, as well as for contract-based privacy protections.

The political impact in Europe of the Snowden revelations inevitably has diminished over the past seven years. Today Europeans worry as much about weak privacy standards in authoritarian countries as about US surveillance practices. In addition, as governments around the world struggle to overcome COVID-19, they see data-tracking technologies as a key part of the solution – and worry less about the attendant privacy risks. Indeed, European governments are embracing data-tracking to a far greater extent than is the United States.

The forthcoming ruling by the European Court of Justice (ECJ)in the Snowden-legacy cases – due to be handed down on July 16 — has the potential to do more than reopen old wounds. Even more ominously, it may cause disarray in transatlantic digital commerce – at a time when governments cannot afford further economic damage.

A new Democratic Administration would be forced to confront the unresolved challenges of keeping data flowing across the Atlantic. How should the US Government respond if the ECJ again finds US privacy protections against surveillance of Europeans’ personal information to be insufficient? Is it finally time for the United States to directly challenge Europe’s efforts to impose its privacy rules on US national security data collection? Is there still room for compromise? Could a comprehensive US privacy law be part of the solution?

Privacy Rules in Transatlantic Commerce

The European Union prides itself on regulating commerce in a manner that is extremely solicitous of potential harms to individuals. It follows the ‘precautionary principle’, under which a product may only be introduced onto the European market if it can be proven to present no risk to consumers. Applying this standard is harder in the case of services than goods, especially when a service is provided from abroad and entails the transfer of personal data outside of Europe.

The EU’s data protection law, the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), provides a way to minimize the risk that individuals’ personal data will be misused when it is transferred abroad. It does so by establishing a ‘border control’ regime for data transfers from Europe. An international data transfer may only occur if there is a legal arrangement in place “to ensure that the level of protection of natural persons guaranteed by this Regulation is not undermined” in other jurisdictions. In other words, a European can rest assured that a company processing his or her data abroad does so in broad conformity with the EU’s privacy rules.

Data has become a central commodity in transatlantic – and global – commerce of all types, not just for services which are delivered using information and communications technology. When a European consumer makes purchases a good from a US online marketplace, his or her personal data travels to America through undersea cables as part of the transaction. Multinational companies are constantly shifting personal data around the globe, for services as mundane as personnel management. Global data transfer rates expanded more than 40 times over the decade between 2005 and 2014, and continue to grow rapidly, particularly across the Atlantic. Cross-border data transfers between the United States and Europe are 50% higher than those between the United States and Asia.

A company importing personal data from Europe into the United States typically chooses between two principal transfer methods, outlined in the GDPR, for guaranteeing the continuity of privacy protection. One is to subscribe to the privacy principles set forth in the US-EU Privacy Shield framework. More than 5300 companies – many small- and medium-sized businesses among them — have done so. The EU deems data transfers made by these companies to the United States to afford an ‘adequate’ basis of privacy protection. The US Commerce Department monitors signatory companies’ compliance with the Privacy Shield principles, and the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) has authority to enforce against those that fail to honor their commitments.

A company’s main alternative to joining the Privacy Shield is to insert into individual contracts for data transactions certain standard privacy protection clauses that have been pre-approved by European data protection authorities (DPAs). In other words, a data importer outside the EU assumes a contractual obligation to handle data in conformity with the privacy terms laid down by the exporter inside the Union. Companies, especially larger ones, widely use standard clauses to transfer personal data from Europe to many parts of the world, not just across the Atlantic. European DPAs enforce compliance with standard privacy clauses.

Privacy Rules and National Security Surveillance Collide

The Privacy Shield, while popular with companies, rests on a shaky legal foundation. It was hurriedly negotiated between Washington and Brussels after the ECJ in 2015 had effectively invalidated its predecessor, the 2000 Safe Harbor Framework. The court did so in response to a petition from Austrian privacy activist Max Schrems, who had read Edward Snowden’s allegations that US social networks were providing foreigners’ communications to the NSA, and believed (without any supporting evidence) that his own Facebook communications had made their way to Fort Meade.

Facebook at the time was using the Safe Harbor Framework as the legal basis for its data transfers from the Continent. Schrems pointed out that a provision in the Framework in fact excused a company from complying with its privacy protections if confronted by a US national security agency’s demand for personal data. Such demands, the ECJ decided, permitted the NSA “to have access on a generalized basis to the content of electronic communications,” and “must be regarded as compromising the essence of the fundamental right to respect for private life…” contained in the EU’s Charter of Fundamental Rights. The ECJ went on to find deficiencies in a number of other features of Safe Harbor, including its failure to provide aggrieved individuals with a right of effective redress for violation of its provisions.

Schrems’ case represented the collision of two worlds – the straightforward one of companies transferring personal data for purely commercial purposes, and the shadowy one of governments obtaining these communications for purposes of protecting national security. It shone a spotlight on the United States, not only because American internet platforms dominate the data transfer business worldwide, but also because US intelligence agencies operate on a much larger scale than do European counterparts.

The EU’s negotiations with the United States to remedy the deficiencies of the Safe Harbor faced legal as well as political hurdles. Since the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights is effectively the equivalent of the US Bill of Rights, ECJ judgments applying its provisions have the character of constitutional jurisprudence. The European Commission, the EU’s executive arm, must scrupulously respect the Court’s holdings, and has only as much international negotiating room as the judges have allowed.

The Privacy Shield remedied some of the ECJ’s criticisms of the Safe Harbor Framework. It strengthened the privacy principles, beefed up the roles of Commerce and the FTC in overseeing compliance, and created an administrative channel for Europeans to complain to an ombudsperson in the State Department if they suspected that the NSA was sifting their personal information.

The United States even sought to address European concerns about national security surveillance. A pair of letters appended to the Privacy Shield from Office of the Director National Intelligence (ODNI) General Counsel Robert Litt described recent changes to the US legal framework for signals intelligence. Litt highlighted the Obama Administration’s issuance, in the Snowden aftermath, of a policy directive (PPD-28) that extended partial privacy protections to foreign nationals and limited the NSA’s bulk collection of certain types of personal data. He also pushed back on the ECJ’s impression that America’s national security data collection efforts were vast. “Bulk collection activities regarding Internet communications that the US Intelligence Community performs through signals intelligence operate on a small proportion of the Internet,” Litt wrote. What US negotiators steadfastly refused to do, however, was to agree to any further limits on their government’s wide-ranging legal authority to surveil Europeans’ communications.

Europe’s privacy activists were distinctly unimpressed by the new, improved transatlantic data transfer arrangement. Soon after the Privacy Shield took effect, a French group filed suit against it in the ECJ. Max Schrems separately chose to refocus his sights instead on standard contract clauses, the alternative transfer mechanism which Facebook, like many companies, had adopted in the interval following the collapse of the Safe Harbor Framework. Schrems observed that standard clauses – like the Safe Harbor — also excuse a company from its privacy protection obligations when confronted by a foreign national security agency’s demand for personal data. He therefore claimed that standard clauses were equally deficient from the perspective of EU fundamental rights. His reformulated complaint gradually made its way back to the ECJ.

Thus, the EU court was presented with parallel challenges to the two major data transfer mechanisms in use with the United States, each case posing similar underlying questions about US surveillance law and practices. At the ECJ’s hearing last summer on Schrem’s challenge to standard contract clauses, the lead judge in the case, Thomas von Danwitz of Germany, also posed questions addressing the validity of Privacy Shield. Suddenly the prospect appeared of the ECJ issuing one judgment deciding the US surveillance issues common to both. US companies which depend on transatlantic data transfers realized they could be facing the perfect storm.

Reckoning Day at the ECJ

In the first stage of deciding an important case like this, a senior court jurist known as an Advocate General (AG) issues an opinion exhaustively analyzing the issues and recommending a resolution. Some months later, the judges release a final judgment, which usually – but not necessarily — follows the AG’s recommendation. The 97-page opinion of AG Henrik Saugmandsgaard Øe of Denmark, issued on December 19, 2019, generated equal measures of relief and alarm for the US government and companies.

Øe first examined whether standard contractual clauses used for transatlantic commercial data transfers measured up to the EU’s fundamental rights standards. He acknowledged that they foresaw the possibility of a foreign data importer being ordered to turn over data to its host government for national security reasons. However, Øe added, the European data exporter, once notified by the foreign importer of the local government’s demand, in turn could ask the relevant EU member state DPA to prohibit the affected data transfer outside the Union from happening. He therefore advised the judges not to take the “somewhat precipitous” step of reaching a broad conclusion about whether standard clauses sufficiently protected Europeans’ privacy rights until a DPA had had an opportunity to consider the particular circumstances of an NSA demand to Facebook. If the ECJ adopts Øe’s perspective, Facebook and the many other companies using standard clauses in transatlantic commerce will, at a minimum, have bought some time, until national DPAs can assess the clauses’ effectiveness in contested cases.

Had the Advocate General stopped there, his opinion would have been embraced as a reprieve for a principal means of transatlantic data transfers. But Øe then went on to analyze the validity of the Privacy Shield itself, paving the path for Judge von Danwitz and his colleagues to decide the merits of both transatlantic data transfer instruments in one combined judgment, if they so choose.

The AG did find Privacy Shield to be an improvement over the Safe Harbor Framework in certain respects. In particular, he concluded that NSA surveillance conducted under the authority of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) did not amount to ‘generalized access’ to the content of electronic communications, since intelligence officials must apply selection and filtering criteria before accessing personal data. If the ECJ agrees, one of the important factual errors it made in the first Schrems judgment will have been corrected.

However, Øe criticized numerous other features of US surveillance law and of the Privacy Shield. He was alarmed by the US government’s extensive reliance on non-statutory surveillance authorities such as Executive Order 12333. He similarly was concerned that privacy protections for non-Americans conferred by PPD-28 could be undone by executive fiat (as indeed President Trump was rumored to be considering early in the current Administration). The AG likewise was unimpressed by the powers of the State Department ombudsperson to operate as an administrative remedy for Europeans, pointing out that the office lacks both investigative powers and independence from the executive branch. It is hard to avoid the conclusion that the Advocate General regards data transfers under the Privacy Shield as failing fully to guarantee EU privacy rights.

The ECJ’s judgment will be handed down on July 16. Most observers agree that the court will find deficiencies in the transatlantic data transfer regime, but they diverge on how far it will go. Will the judges assess only the validity of standard contract clauses, as the Advocate General urges, or will they go beyond to draw conclusions about the Privacy Shield as well? If the court finds Privacy Shield wanting, will the arrangement effectively be invalidated with immediate effect, as occurred in the case of the Safe Harbor? Or might the ECJ instead grant the European Commission a reasonable interval to renegotiate the Privacy Shield with the United States?

Towards a US Strategy for Ending the Privacy Wars

Ever since the Snowden allegations erupted, American companies have looked in vain for a lasting legal foundation for vital transatlantic commercial data transfers. The US Government’s own frustration also occasionally has emerged into public view. In the wake of the Schrems judgment’s sharp criticism of US surveillance practices, President Obama pointed to the deafening silence from European governments on the important role US intelligence plays in protecting Europe’s national security:

…a number of countries, including some who have loudly criticized the NSA, privately acknowledge that America has special responsibilities as the world’s only superpower; that our intelligence capabilities are critical to meeting these responsibilities; and that they themselves have relied on the information we obtain to protect their own people.

If the ECJ again rules against transatlantic data transfer mechanisms, it is not hard to imagine a US Administration concluding that negotiated solutions with Europe have not worked and turning to a confrontational posture. It certainly has the tools. The Executive Branch could turn off intelligence sharing with European allies and wait for the yelps from their security services to reach Brussels. Alternatively, US internet platforms might be quietly urged temporarily to stop providing the services that Europeans daily depend on.

US companies surely would press the Administration to pursue a further negotiated privacy arrangement with the European Union, however. Some ECJ objections to US surveillance laws could be addressed through Congressional action and reflected in a revised Privacy Shield. But not all judicial criticisms would have a reasonable prospect of Congressional remedy – so it is important that the court not overreach.

The ECJ might, for example, find that important and long-established US surveillance authorities embedded in executive order rather than statute do not measure up to European fundamental rights norms. The court also could demand specific changes to US bulk surveillance practices, such as the methods the US intelligence community uses for selecting and filtering which tranches of personal data to scrutinize. It is difficult to foresee Congress being sympathetic to such concerns, particularly in the current turbulent era of transatlantic relations.

The ECJ might well also point to the need for the United States to strengthen the institution of the ombudsperson as an arbiter of Europeans’ complaints about surveillance of their personal data. Congress should sympathetically consider making the ombudsman independent of executive branch influence and granting it autonomous investigative powers as well. There is in fact an existing agency within the US government well-suited to take on such a remedial function — the Privacy and Civil Liberties Oversight Board (PCLOB). Congress could grant the PCLOB, a small but respected independent agency currently charged with privacy oversight of US counter-terrorism laws, the additional authority and resources to scrutinize national security access to personal data transferred to the United States for commercial purposes.

The ECJ additionally may confirm Advocate General Øe’s doubts about the legal durability of PPD-28. Transforming privacy elements of this directive into the form of a statute would greatly strengthen European confidence that they cannot easily be undone. Congressman Eric Swalwell (D-CA) in fact proposed this step in an unsuccessful amendment to the 2018 bill reauthorizing Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act. Legislating portions of PPD-28, together with strengthening surveillance oversight by an independent ombudsperson, would go a long way towards overcoming European legal objections to the Privacy Shield and standard contract clauses.

Beyond these concrete steps, the very act of the US Congress passing comprehensive privacy legislation would be persuasive evidence to Europe and the rest of the world that the United States takes seriously key privacy principles such as limits on consent and on use of data, and redress. Congress in recent years indeed has inquired into the GDPR, taking testimony from leading European privacy regulators about how their experience could inform US comprehensive legislation.

Most importantly, enacting a comprehensive US privacy law would present a credible case to Brussels that transatlantic privacy protections are broadly congruent, even if they inevitably diverge in some respects. No longer would the US Government be condemned to repeated, piecemeal attempts to disprove alleged deficiencies in its system of privacy protection. Instead, the EU and the United States finally could develop a definitive regime for transatlantic commercial data transfers based on reciprocal respect for each other’s legal systems.

Congress showed it could exercise global leadership on international data transfers when it enacted the 2018 CLOUD Act to allow law enforcement authorities rapid and efficient access to electronic evidence located abroad. Foreign authorities may only obtain e-evidence located in the United States if their requests meet due process standards comparable to the rigorous ones of US criminal law.

Ever-larger portions of the future transatlantic economy will run on data flowing in both directions. If the United States and Europe are definitively to end the privacy wars that intermittently have flared between them, the protections that accompany the transatlantic movement of personal data must become a two-way street as well.

Biden and BLM must set aside differences, focus on beating Trump

Joe Biden isn’t nearly as visible, but he’s leading President Trump in every key battleground state and even some – including Texas – that no one expected to be up for grabs in 2020.

At the same time, the former vice president is taking heat from Black Lives Matter (BLM) and the progressive left, who complain that his stance on policing and criminal justice reform is too tepid.

These divergent realities reflect two large tensions that Biden must manage adroitly to unite his fractious party and prevent Trump from winning in November.

Read the full piece here.

Americans are Worried about Health Care Prices — What Can Congress Do?

The Trump administration’s hospital price transparency rule, upheld by a district court judge this week, will require hospitals to post publicly the rates they negotiate with insurers beginning in January.

President Trump called it a “BIG VICTORY for patients — Federal court UPHOLDS hospital price transparency. Patients deserve to know the price of care BEFORE they enter the hospital. Because of my action, they will. This may very well be bigger than healthcare itself.”

This is undoubtedly false. Price transparency is always a good thing, in health care or any other market. But the effect of Trump’s order is likely to be modest at best.

The idea is that if prices are posted, informed consumers — aka patients — can compare prices between providers for elective surgeries and procedures. This would encourage them to pick lower cost providers and subsequently, providers would lower their prices to remain competitive.

But the jury is still out on how much affect price transparency could have on overall health care costs. One study found that only 2 percent of patients with health plans that offered price transparency tools used them. There are three main reasons that patients are not responsive to price in health care:

1. People with insurance are insulated from health care costs at the point of purchase

2. Patients follow their doctors’ referrals rather than shopping for care on their own

3. Patients see price as a proxy for quality and associate higher prices with higher quality care

Even though they don’t price shop, Americans are still concerned about health care costs. Before the pandemic, 1 in 3 Americans were worried about being able to afford health care. Though price transparency isn’t likely to change consumer behavior, it could help insurers negotiate better prices with hospitals. It remains to be seen. But in the meantime, hospitals are appealing the court’s decision.

To support efforts to reduce health care prices, Congress could:

Require hospitals to post prices publicly. Codifying the rule would render the lawsuit challenging the Trump rule moot.

Empower the FTC. Giving the Federal Trade Commission more resources to review and limit hospital mergers could reduce health care prices. Hospital mergers are continuing despite the pandemic and cash-poor physician practices are selling out to larger hospital chains. The data show that consolidated markets have higher health care prices. Giving the FTC more resources to consider the market implications of these mergers and acquisitions could limit market consolidation and price increases.

Ban surprise bills. Congress could resume negotiations over a comprehensive package to ban surprise medical bills. My preferred approach is a benchmark price for out-of-network services tied to Medicare prices. Tying the benchmark to in-network prices or median charges has perverse incentives to increase in-network prices. Is it politically difficult? Yes. But it’s necessary to both protect patients and to stop the exponential growth of health care costs in the U.S.

Read more here.

The GOP’s “Spread Covid” Tax Credit May Be Its Dumbest Pandemic Proposal Yet

As Congress prepares to pass another round of coronavirus relief, Republicans have once again fallen back to their failed cure-all solution: another tax cut. So far they’ve proposed cutting payroll taxes for high-income workers, cutting capital gains taxes for wealthy investors, and providing tax subsidies for business expenditures on meals and entertainment. None of these are particularly good ideas, but the latest one – introduced in the U.S. Senate by Sen. Martha McSally (R-AZ) and supported by some members of the Trump administration – may be the most ineffective, regressive, and counterproductive economic “stimulus” policies proposed to date.

Read the full piece here.

Congress Should Stabilize The American Economy – Both Now And Later

At the end of next month, several economic support programs created by the CARES Act in March will expire. House Democrats have moved to extend and expand these supports through January 2021 with the $3 trillion HEROES Act. Senate Republicans, however, have used fiscal cost as a pretext to oppose or scale back this and other potential future stimulus measures. The stakes are high: allowing the CARES Act programs to expire would reduce the incomes of up to 30 million unemployed Americans by more than half overnight and cut off lending programs that have helped otherwise healthy businesses stay afloat during the crisis. Fortunately, there is an opportunity for lawmakers to strike a bipartisan compromise that supports our economy in a fiscally responsible way.

Read the full article here.

Now is the Time to Connect Rural America to Broadband

A broadband connection has become an essential lifeline, especially during COVID for our shuttered offices, schools, places of worship, and retail stores. For many, a digital connection has become the safest and most timely way to seek medical attention, continue education, assist customers, and check-in with friends and loved ones.

95% of American homes have ways to access a broadband connection today – a result of the nearly $2 trillion in investment over the last two decades that flowed from a pro-competition, light-touch regulatory approach. That’s good news.

The bad news is that in rural America, 22 percent of homes lack access to a fixed broadband connection at the FCC minimum 25/3 Mbps speed because it’s too expensive to build in these sparsely populated communities. That puts rural America at a distinct economic disadvantage to the rest of the country. And that’s wrong.

Past efforts to get at this problem have fallen short both because they failed to focus on unserved areas and because outdated rules often locked out some of the most cost-effective solutions.

Much like the challenges of rural electrification, it will take an all hands-on deck approach and the right policy framework to wire rural America with broadband.

The recently passed CARES Act included more than $300 million for rural broadband and telehealth services. The Rural Digital Opportunity Fund (RDOF) — the FCC’s next step in bridging the digital divide — will direct up to $20.4 billion over ten years to finance up to gigabit speed broadband networks in unserved rural areas, connecting millions of American homes and businesses to digital opportunity.

The Connect America Fund (CAF) — part of the Universal Service High-Cost program — is an FCC program designed to expand access to voice and broadband services for areas where they are unavailable. In the CAF Phase II, the FCC will provide funding to service providers to subsidize the cost of building network infrastructure in census blocks where internet service is lacking.

But these programs can only succeed if we learn from the mistakes of the past and instead focus on building out in unserved areas and removing anti-competitive red tape.

These buildout programs often mandate nearly three-decade-old eligibility requirements that were initially designed to ensure that companies who sought federal funding could get the job done. But today, these eligible telecommunications carrier (ETC) requirements, are doing the opposite – they are screening out some of the most able-bodied competitors and slowing down progress.

Rather than defining one set of federal eligibility requirements, the current ETC rules allow states to set up a patchwork of pet projects – poorly defined Green New Deal requirements, forcing broadband builders to serve as back-up electrical utilities, and other collateral projects — that data has shown have nothing to do with universal buildout in rural America. Many of the most experienced broadband companies simply don’t participate as a result.

To cut the mountains of red tape and speed up broadband expansion to those Americans most in need, Rep G. K. Butterfield (D-NC) introduced the Expanding Opportunities for Broadband Deployment Act. This bill will create one standard to ensure the best companies are competing under the same rules nationwide. This is likely to spur competition, which will in turn mean lower costs and better results for taxpayers and rural Americans.

If we want meaningful results in connecting rural America to broadband, Congress should pass the Butterfield legislation and retire the patchwork ETC process that is holding back progress.

One national, pro-competition standard is just what we need to get better and more cost-effective solutions to the table, and to finally make real progress in solving the lack of broadband in rural America problem.

COVID-19 is unraveling the issue of surprise billing in America

Back in December, Congress failed to reach an agreement on “surprise billing” legislation. A surprise bill is when patients get an out-of-network bill from a provider at an in-network facility.

Lawmakers couldn’t decide if an arbitration model — where billing disagreements would be sent to a third-party review board — or if a benchmark model — where payments would be based on a set benchmark price — was best.

Now in the era of Covid, this failure is coming home to roost.

Federal law requires private health plans to cover all Covid-19 testing. But because there is no set benchmark price labs can charge whatever they want as long as they list it publicly. Most labs charge around $100 for a Covid-19 test, some unscrupulous labs are charging as much $2,315 for the same test.

Patients, of course, will ultimately bear the cost through higher premiums. Furthermore, the failure to ban surprise bills means that out-of-network labs can balance bill the patient on top of the fee they charge their health plan. Balance billing is when an out-of-network lab or hospital first bills insurance but because there is no agreed upon price, then balance bills any remaining balance the insurer refuses to pay back to the patient.

Labs aren’t the only ones inflating costs to exploit the Covid-19 emergency. Some hospitals are billing patients hundreds of thousands of dollars for treating the disease, even though hospitals that take federal bailout dollars are supposed to be barred from balance billing patients. This is because even if the hospital takes federal funding, if the doctors that work there are out-of-network, they (or their staffing companies) can send surprise bills to patients.

But there are some policy levers that could help:

Bar billing above what Medicare pays. Medicare initially was paying $50 per Covid test. But because supply was lagging, it upped its reimbursement to $100 to encourage more testing. It seems to have worked — supply for Covid tests is roughly aligned with demand. Congress should limit all labs that take Medicare payments from billing private insurers above the rates set by Medicare.

Ban surprise Medical bills. Congress could resume negotiations over a comprehensive package to ban surprise medical bills. My preferred approach is a benchmark price for out-of-network services tied to Medicare prices. Tying the benchmark to in-network prices or median charges has perverse incentives to increase in-network prices. Is it politically difficult? Yes. But it’s necessary to both protect patients and to stop the exponential growth of health care costs in the U.S.

Consider a global budget. Hospitals do have a revenue problem. That’s mainly because many stopped doing lucrative “elective” procedures to concentrate on handling the surge of Covid-19 patients. But hospitals that have a “global” budget are better positioned to weather the Covid storm. A global budget is a fixed amount of money all payers in a region agree to pay hospitals to deliver care to a defined population. All Maryland hospitals, for example, and more recently rural hospitals in Pennsylvania, use global budgets to pay for medical care. This model eliminates incentives for hospitals to jack up prices for Covid-19 services to compensate for the loss of normal revenue. A recent analysis in JAMA outlines why these hospitals will be better positioned to bounce back from Covid-related economic hardship. While moving to a global budget will be difficult, it makes more sense now than ever and policymakers should not let the moment pass.

Read more here.