INTRODUCTION

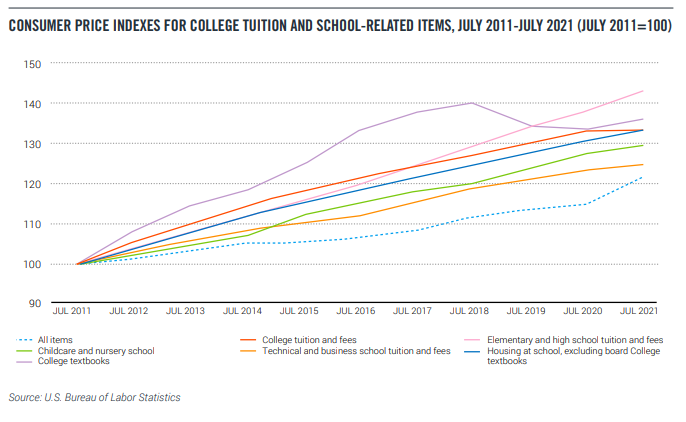

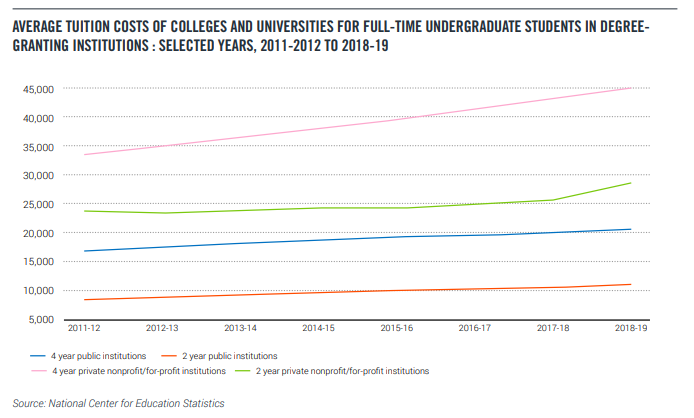

Over the last 30 years, college tuition has skyrocketed. From 1988 to 2018, tuition at public four-year institutions (in real terms) rose 213%. The numbers for private tuition are also stark, with a jump from 1988 to 2018. Students at public four-year institutions paid an average of $3,190 in tuition for the 1987-1988 school year, with prices adjusted to reflect 2017 dollars. Thirty years later, that average has risen to $9,970 for the 2017-2018 school year.

The price jump at private schools has also been significant. In 1988, the average tuition for a private nonprofit four-year institution was $15,160, in 2017 dollars. For the 2017-2018 school year, it’s $34,740, a 129% upsurge.

In response to the exponential surge in the cost of higher education, policymakers have focused increasingly on proposals to expand financial aid and loans, and canceling the vast sums of debt that college students have accumulated. Calls for canceling student debt are understandably popular with those burdened with those loans. But student loan forgiveness is a one-off gift to one generation of borrowers, that does nothing to prevent the problem from repeating itself year after year.

The first step to make college more affordable and expand access to more Americans is to increase price transparency about the true cost of college, and ensure prospective students get credit for college-level work they have completed before starting their degree.

Presently, students lack the information they need to make smart choices about if and where they should go to college. Colleges and universities are not transparent about the true cost of tuition and fees and are opaque about how much credit (if any) students can earn before enrolling (which in turn can reduce the cost). As a result, too many students aren’t getting the college credit they have earned and are being forced to pay and borrow more than they should.

As the pandemic abates, higher education institutions must commit to holding down the cost of tuition and helping students reduce the amount they have to borrow. For example, colleges should guarantee up to two semesters worth of credit for successful completion of Advanced Placement (AP), International Baccalaureate (IB), and college courses taken in high school. They should also make the transfer of credits from community colleges more seamless.

This paper offers a series of pragmatic steps policymakers could take immediately to curb college costs and borrowing. The federal government should use the leverage of billions in financial support for higher education to increase transparency around tuition price, credit transfers, and acceptances so that students can make more informed decisions around college costs:

1.) The White House should push for legislation that gives the Department of Education greater authority to establish policies for AP, IB, and dual enrollment course credit and ensure that these credits transfer automatically.

2.) Colleges should be required to disclose before a student matriculates the number of credits, including through AP, IB, or from community college coursework, that will be accepted.

3.) The Department of Education should require that colleges provide easy access to information on transfer credits.

4.) States should set clear standards for minimum tests scores on AP tests and GPA-level coursework required to earn college credits.

BACKGROUND

The skyrocketing cost of higher education has become a millstone around the necks of young Americans. More than one in five U.S. households hold a student loan, up from one in 10 in 1989.1 According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the cost of college has increased by nearly five times the rate of inflation since 1983.2

These increases depend on the type of institution a student attends, and tuition hikes have been most pronounced among four-year private universities.3 Overall, researchers point to state disinvestment in colleges and rising administrative costs as key drivers of higher education costs.

The education debt crisis has disproportionately affected millennials4, who are already saddled with lower wages and lingering economic pains from the Great Recession. Of young adults aged 25 to 34, or the bulk of millennials, approximately one-third hold a student loan.5 Collectively, as of 2019, 15.1 million millennial borrowers hold $497.6 billion in outstanding loans.6 Economists have pointed to this massive debt burden as a key reason why millennials are not buying houses, starting small businesses, or saving for retirement in the same way as past generations, and it is to the overall detriment of the economy.7

Those who have borrowed for degrees are more likely to be lower-income, Black, and less likely to have family wealth to fall back on. Thus, they are more likely to default, exacerbating poverty and the racial wealth gap. According to the U.S. Department of Education, 20% of borrowers are in default, and a million more go into default each year. Two-thirds of borrowers who default never completed their college degrees or earned only a certificate and owe a comparatively low average amount of $9,625.8 Those who default include veterans, parents, and first-generation college students.9 This “debt with no degree” syndrome leaves borrowers in the hole without access to the earning power associated with a postsecondary degree.

Pell Grant recipients from lower-income households represent an exceptionally high percentage of defaulted borrowers. For example, close to 90% of defaulters received a Pell Grant at one point.10 Of this group, even those who earned a bachelor’s degree are three times more likely to default than students from families that don’t qualify for a Pell Grant.11

For young people who borrow heavily and get in over their heads, default often has catastrophic implications for future access to credit. Many have their wages garnished and tax records seized, starting adulthood and careers on the wrong foot.12

DIMINISHING CREDIT FOR COLLEGE LEVEL COURSEWORK COMPLETED IN HIGH SCHOOL

More high school students are graduating with college-level coursework that could help alleviate some of these costs. High schools with AP and IB programs, as well as Early College high schools,13 give students a head start on advance credits. But many colleges are not transparent about which of these credits will transfer once students matriculate.

According to data from the National Center for Education Statistics, nearly 71% of community college students intend to, at some point, pursue a baccalaureate degree.14

Adding to their data, studies from the Center reveal that approximately 20-50% of new university students are actually transfer students from community college. As students move between institutions, they find it very difficult to navigate the system of credit transfers and agreements.

In fact, colleges have made it increasingly difficult to receive course credit for AP, IB, and work completed at community colleges.15 Some schools (Dartmouth, Brown, and Williams, to name a few) have stopped granting course credit entirely for AP. Furthermore, only 20 states have statewide policies for AP course credit, and more often than not, those that do have statewide policies do not have a minimum score guaranteeing credit transfer.

Why are schools restricting the use of AP? Many claim AP courses are not an actual substitute for college courses. Yet most of these schools that restrict credit are willing to grant those same students’ waivers out of many college courses, which underscores that AP courses are perfectly acceptable substitutes for college courses. A more likely reason is revenue, as more and more schools have become dependent on tuition in order to keep operating.

HIGHER EDUCATION’S TRANSPARENCY PROBLEM

To say that higher education has a transparency problem is an understatement. No industry, with the possible exception of health care, makes it more difficult to compare costs and lock-in an actual price.

Many have long recognized this problem, but efforts to get schools to provide basic pricing information has lagged. For example, work conducted by researchers at the University of Pennsylvania noted that some colleges do not comply with federal rules requiring net-price calculators, while others offer “misleading,” “incomplete,” or dated information about price.16

Another problem is inconsistent financial aid offers — sometimes loaded with obscure and overly complex language, or sometimes omitting the cost of attendance altogether, according to New America and uAspire’s report, Decoding the Cost of College.17

Students looking for information on credits for Advanced Placement work or courses completed at community colleges often have to wait until they arrive on campus. Most schools have made it increasingly difficult to figure out how much AP credit will be awarded, with many leaving that decision to university and college departments. And more and more schools are offering only waivers or exemptions, instead of actual course credit that can reduce the cost of tuition.

What information schools do provide is often vague and confusing. As the reprint below of an agreement between Johns Hopkins and Prince George’s Community College on course transfers highlights, many school websites provide no more than a low-quality copy of legal language that raises more questions than it answers.

The federal government has attempted to address some of these issues, but most of these reforms have proven ineffective because neither party is willing to use the billions in federal support for higher education as leverage.19

MAKING FEDERAL AID CONTINGENT ON PRICING AND ADVANCED CREDIT TRANSPARENCY

During his campaign, President-elect Joe Biden proposed creating a more seamless process for earning credit for college-level work completed prior to enrolling as an undergraduate (dual enrollment). The Biden administration should fast track this effort in two steps.

First, President Biden should direct the Department of Education to create a federal website where prospective undergraduates could access simple and clear information on the AP, IB, and dual enrollment policies of undergraduate institutions. Trying to find whether your AP test score or that community college class you took will earn you credit at a particular college is like looking for a needle in a haystack. Schools often bury this information on their website, or even worse, don’t provide it all. This lack of transparency can often deter prospective students from even trying to get credit for work that should qualify.

Second, the Biden administration should require schools that receive federal aid to provide admitted students with a detailed spreadsheet of how much credit they will or won’t receive from AP, IB, and dual enrollments prior to their matriculation. No student should have to wait until they arrive on campus to learn how many courses they need to take (and how much money they will have to spend) to graduate.

Accessing early college coursework opportunities can make high school more relevant, increase college-going, make higher education more affordable, and provide a financial lifeline to eligible colleges struggling with depressed enrollments. College-level coursework through AP, IB, and dual enrollment can be motivating to disadvantaged students. It facilitates completing a degree faster and at lower total cost to students and their families.

Of course, neither of these policies would reverse the impact of those colleges and universities that have made it increasingly difficult to get actual course credit for AP, IB, and work completed at community colleges. To truly bring down the cost of tuition and the debt burden on future students without relying completely on federal subsidies, a Biden-Harris administration will need to push for legislation that gives the Department of Education greater authority to establish policies for AP, IB, and dual enrollment course credit.

For example, colleges and universities should be prohibited from capping the amount of credits one can earn towards their degree outside from AP or community college coursework. As long as the students meet the minimum requirements, credit should be granted automatically.

In addition, schools would be required to agree to a universal minimum test score for all AP subject matter tests and a GPA level for coursework at a community college.

These two reforms would help millions of future college students reduce their tuition bill and get them into the job market or graduate school sooner.

CONCLUSION

Promises of massive debt cancellation and increased federal aid are popular with students, but they won’t fix the higher education system’s broken financial model. Instead, they’ll pour more taxpayer money into an opaque, high-inflation college sector and generate new waves of debtladen students and families. We need to break this pernicious cycle by rethinking transparency in higher education with a focus on bringing down costs through a more seamless and transparent process for credit transfers.

Policymakers should require increased transparency on AP and IB credits as part of acceptance packages, as well as ensure that credits transfer more easily between institutions. These will help students and families better plan for the cost of a postsecondary education, and reduce the bills for those who matriculate or transfer with college-level coursework.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Paul Weinstein Jr. is a Senior Fellow at the Progressive Policy Institute and Director of the Graduate Program in Public Management at Johns Hopkins University.

Veronica Goodman is the former Director of Social Policy at the Progressive Policy Institute.

REFERENCES