Community colleges should be matching students to jobs, not funneling everyone into a four-year degree. A response to Richard D. Kahlenberg.

The United States is facing one of the greatest workforce challenges in recent history. Wages have been stagnant for a decade and middle-skill jobs have evaporated—and yet unfilled vacancies for high-wage computer and tech jobs are at record levels. Few have been as badly affected by the shifting landscape of the labor market as young Americans, who must adapt to the global competition for jobs with no guarantee of a secure retirement. Already a wealth gap exists relative to older generations at their age, and lower net worth, alongside rising student debt, will inevitably leave lasting economic scars.

In his recent Democracy essay [“Community of Equals?,” Issue #32], Richard Kahlenberg correctly points out that the failure of our nation’s community colleges is partly to blame. He rightly emphasizes the important role community colleges play in the well-being of our nation’s workforce, writing, “Their success or failure will help determine whether America remains globally competitive and whether American society can once again promote social mobility in an era of rapidly changing demographics.”

So ineffective have community colleges become that they are hardly considered a viable pathway into the workforce. In fact, a four-year credential seems to be the only acceptable postsecondary pathway; you either earn a bachelor’s degree or accept a fate of underemployment and low pay. It follows that since 2000, the number of two-year colleges has remained flat while the number of four-year institutions has increased by more than 400, or 17 percent. There are now about 2,900 four-year colleges in the country, or roughly one four-year institution for every U.S. county.

Kahlenberg wisely advocates reforming the entire community college system. However, his analysis and proposed solutions are flawed in three important ways. First, community colleges are failing not because of de facto segregation, as Kahlenberg insists, but because they don’t adequately prepare students for the workforce. The best way to fix this is through private-sector engagement, not heavy-handed government intervention. Second, the goal of community colleges should be to prepare students for the workforce, not just to pave a path to a bachelor’s degree, as Kahlenberg suggests. Finally, failure within the postsecondary education system is not confined to two-year colleges. Four-year colleges are also facing serious challenges.

The first flaw in Kahlenberg’s analysis is his foregrounding of socioeconomic segregation as the main problem facing community colleges. He writes, “[O]ur higher education system, like the larger society, is increasingly divided between rich and poor, an arrangement that rarely works out well for low-income people.” He suggests that the demise of community colleges stems from a vicious cycle of reinforcing racial and low-income stratification, where only poor people go to community colleges while better-off people get an automatic pass to attend a four-year institution.

Kahlenberg offers the fact that four-year colleges enjoy greater government support as proof of inherent preferential treatment toward more affluent Americans. He laments that “direct federal aid to higher education disproportionately benefits four-year over two-year colleges” and that “wealthy four-year universities receive large public subsidies in the form of tax breaks that are largely hidden from public view.” Yet this is hardly proof of income or racial bias. Four-year colleges are more expensive, and provide a longer, more comprehensive service than community colleges, so it’s not surprising that more federal aid goes to four-year institutions. Moreover, if private nonprofit schools are able to use tax-supported donor funds to defray rising costs instead of increasing tuition or relying on students to take on more debt, then that should be applauded, not assailed.

By focusing on segregation, Kahlenberg misses the fact there are other factors at play. For example, our nation’s K-12 education system bears much of the blame for perpetuating the failure of community colleges. Too many young Americans graduate from high school without rudimentary skills, forcing community colleges to retrain students in basic education. For instance, the Northern Virginia community college system—an exemplary system by Kahlenberg’s definition because it grants automatic admission to Virginia state universities upon completion—offers a course in learning “whole numbers.” But I found no courses specifically in SAS, STATA, Eviews, or other statistical analysis software that high-wage employers are looking for. By being forced to offer mainly remedial courses, such community colleges disserve the many students who do have basic skills and prohibit the integration of people from different backgrounds that Kahlenberg strives to encourage.

In reality, our community colleges are failing for a reason more obvious than a socially ingrained elitism. It’s because they aren’t providing students with a positive return on investment. They are not adequately preparing their students for the workforce with dynamic training programs that align with local employer demands.

Indeed, the best way to promote economic and social mobility is to prepare our workforce for jobs that match such demands. The key is to engage the private sector: the employers. They must be an active partner to community colleges, participating in curriculum design and engaging with prospective hires. Nowhere in his essay does Kahlenberg mention the role of the private sector, leaving a rather large hole in his analysis.

Instead, the author’s proposed reform of reallocated government spending will only preserve the status quo. Worse, it would exacerbate the skills mismatch, as community college administrators would have little incentive to work with local employers. His focus on bringing in more middle-class students to community colleges would also do little to help millions of struggling young Americans of all backgrounds.

Real reform of community colleges would also engage the education-technology revolution that is passing too many postsecondary education institutions by. Low-cost, high-speed broadband has the potential to transform workforce training, creating enormous economic and social opportunity by including people of all socioeconomic backgrounds. For example, the University of Colorado’s College of Engineering and Science recently launched a program to help its students master communications technologies to collaborate with engineers from around the world. Designed to teach students the online skills they need to succeed in business, the program saw a diverse student body—50 percent female, 30 percent Latino—in its first year. The emergence of massive open online courses and customized education is also of great promise, and could even encourage higher completion rates—an area of concern in the postsecondary education industry.

If community colleges realigned their mission to prioritize workforce preparedness, the growing socioeconomic divide Kahlenberg writes about would likely be to a certain extent reversed. Perhaps more students of varied backgrounds would want to enroll if they knew the associate degree held more clout in the workforce. The segregation that plagues today’s system would improve organically, in a virtuous cycle, without heavy-handed government mandates.

A second problem with Kahlenberg’s essay is his assumption that the end goal of the community college system is for everyone to get a four-year degree. Here Kahlenberg is not alone; it seems as if the bachelor’s degree is seen by the entire postsecondary education industry as the Holy Grail for the economic woes that afflict young Americans.

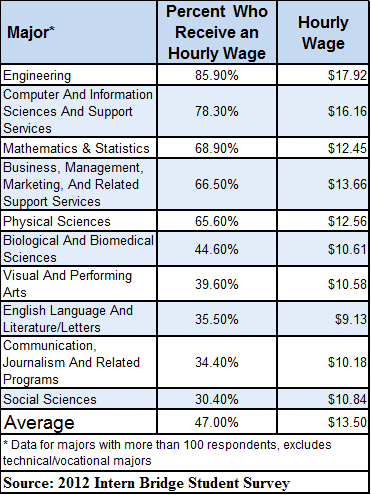

This is simply not true. Not every job requires a four-year degree and not everyone needs one. For example, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, over the next decade new jobs requiring either an associate degree or a postsecondary non-degree award are expected to grow faster than jobs requiring a bachelor’s degree. Many of these jobs—such as those for medical or engineering technicians, or for computer support specialists—pay well and are vocational or technical. This suggests some four-year students could probably get a better return on investment from a two-year credential or non-degree certification.

The fact is that when it comes to a bachelor’s degree, it matters where you go to school and what you study. While on average those with a bachelor’s degree earn $1 million more in their lifetime than those without, the variance in return on investment is large.

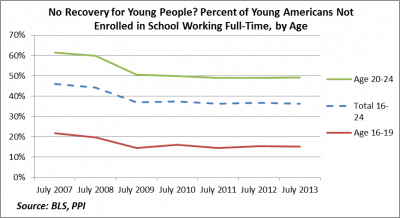

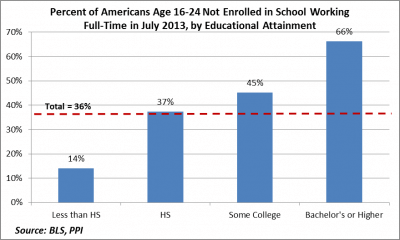

There is no question that some form of postsecondary training or education is necessary in today’s economy. Young Americans without education beyond a high-school diploma are dropping out of the labor force at an alarming rate, or working less, unable to compete for decent jobs. But the question we should be asking is: What type of postsecondary credentials do we need? We must design postsecondary education policies that reflect the reality on the ground by promoting more alternative pathways into the workforce outside of a bachelor’s degree.

This brings us to the third flaw in Kahlenberg’s analysis. By wanting to funnel everyone into four-year schools, he ignores the fact that the four-year model is already beginning to implode. It turns out that the recent building binge of four-year colleges may not have been the greatest idea, as we are now saddled with many ineffective four-year schools. A painful truth is that the failure of postsecondary education is not confined to community colleges, and many four-year institutions are also facing tough questions from students and parents.

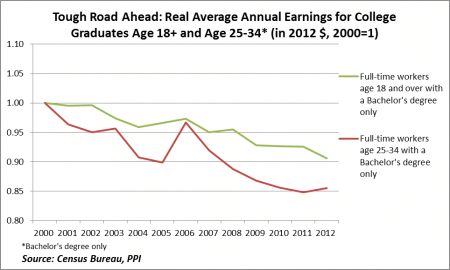

Young college graduates know all too well that having a bachelor’s degree is not a guaranteed ticket to financial success. They have seen their real average annual earnings drop by 15 percent over the last decade, as the hollowing out of middle-skill jobs over that time has forced more graduates to take lower-paying jobs that do not require a four-year degree. In fact, my research has shown that college graduates are forcing those with less education and experience out of the labor force—what I call the “Great Squeeze.” At the same time, they face rising student debt levels, now more than $29,000 per borrower. Too many young Americans are leaving the postsecondary education system with thousands in debt and little to show for it.

In his essay, Kahlenberg argues that four-year institutions provide a better service because they spend more per student than community colleges. He notes that “stunningly, over the past decade, inflation-adjusted spending on public research universities has increased roughly $4,200 per student, compared with just a $1 per student increase for community colleges.”

But this just shows how much more expensive it is to provide everyone with a four-year degree. Further, it wrongly assumes that because four-year research universities spend more per student, the student is getting a better education. The most recent data shows in that 2011, public universities spent more on “auxiliary enterprises,” which includes bookstores, dorms, and dining, than on academic support and student services.

Moreover, public funding for postsecondary education has been decreasing across the board, with four-year colleges also feeling the pinch. In Colorado, for example, annual public funding for postsecondary institutions is expected to decrease to zero by 2022. As state spending falls and tuition rises, the federal government has shouldered the burden of ensuring equal access. This includes the expansion of federal student aid and programs like income-driven repayment. According to the College Board, Pell grants are up 118 percent over the last decade. It turns out the increased spending per student at public universities is being paid for in large part by the student and the taxpayer.

By encouraging everyone to get a four-year degree, we will add more debt on the backs of young Americans and put greater strain on the federal aid system. This is especially true if more young Americans feel obligated to pursue graduate school to stand out to employers, taking on even more debt in the process. We need to have other viable pathways into the workforce that don’t require major time and financial commitments.

What we need is a community college system that can stand on its own. It should be a standard, if not common, pathway into the workforce. Its success should depend on how many students are able to achieve a decent standard of living upon completion, with transfers into four-year colleges as one possible option. Certainly, some colleges are getting the formula right, leading the way with innovative practices and programs that integrate local employers to the benefit of their students. Yet such cases remain the exception rather than the rule.

The goal of the postsecondary education system should be to facilitate America’s workforce preparedness. Only when we realize that multiple pathways are needed to reach this goal—rather than a one-size fits all approach—will we undertake the radical reforms we truly need.

This article was originally posted by Democracy.