Yesterday a coalition of eight Senators finally announced a deal on federal student loan interest rates. The compromise, which takes cues from previous proposals from the White House and House Republicans, will peg interest rates on all new federal student loans to the rate on 10-year Treasuries plus a margin. The deal, several months in the works, will retroactively replace the doubling of interest rates that took effect July 1.

Senate Democrats, who had wanted more generous terms for students, are calling the deal more of a grand rip-off than a grand bargain for students pursuing college. Although the deal calls for capping interest rates, they argue that even with the caps borrowers will still pay higher rates than before, especially as the economy improves and interest rates rise. Moreover, according to CBO estimates, the deal will increase federal student loan profits by additional $700 million over the next decade – all on the backs of innocent parents and students.

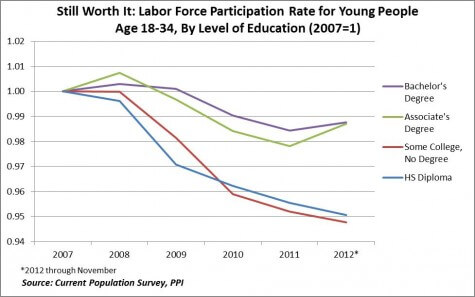

This deal should be seen as a reasonable compromise. As I’ve written before, interest rates are only a small part of the actual problem facing student debt. Whether interest rates are 6.8 percent or 8.25 percent (the deal’s new cap for unsubsidized Stafford loans, which most undergraduates get) makes little difference in an economy where half of recent college graduates are underemployed or unemployed, and where real earnings for young college graduates are falling. It does little to address what’s really bloating the amount students owe – ever-rising principal from higher tuition – and it does nothing to address the existing $1.2 trillion mountain of outstanding student loans.

Moreover, it’s not clear pegging long-term student debt to short-term debt borrowing costs, like the federal funds rate or 1-month Treasuries, is the best approach. Such term mismatching – borrowing on short-terms and lending on longer-terms – can be risky, especially for student loans, which are uncollateralized and dependent on future earnings.

If Senate Democrats are unhappy with the deal, they should take the rising burden student debt seriously when they review federal student loan programs for the reauthorization of the Higher Education Act (HEA) later this year. That will be a great opportunity to address one of the biggest issues of our time: helping young people succeed in today’s economy.