INTRODUCTION

The Covid-19 pandemic has sent the global economy and financial markets into an unprecedented crisis. The path of the downturn and recovery is difficult to discern. Some companies and nations are likely to survive and prosper, while others will struggle indefinitely.

In this context, bond markets will be looking to rating agencies to objectively assess the changing prospects of bond issuers, both private and public. Even the Federal Reserve is counting on the rating agencies—the Fed’s own rules for which bonds it can purchase under the new Primary Market Corporate Credit Facility explicitly reference the ratings produced by major nationally recognized statistical rating organizations (“NRSRO”).1

Can the credit rating agencies be trusted to do a good job analyzing the credit prospects of borrowers in the downturn? Will the resulting rating actions balance the needs of investors, issuers, and the financial markets? Will ratings downgrades unnecessarily make the economic and financial situation worse?

Before the virus struck, two independent advisory committees at the SEC in the United States were in the process of examining the business and compensation models of credit rating agencies such as Moody’s Investors Service and S&P Global. The issue was whether their “issuer pays” business model gives them an incentive to inflate the initial ratings of corporate bonds and other securities, or an incentive to slow-walk necessary ratings downgrades in tough times. Several meetings were held at the SEC in 2019 and 2020 to discuss alternative compensation models that might not have the same conflicts of interest.

But despite these criticisms, the strengths of the current model of fixed income credit ratings— built around transparency and reputation—are often overlooked.

The market for ratings for fixed income securities has developed a set of incentives and institutions that consistently produce strong signals that are useful for market participants, even in uncertain times.

This paper examines the pluses and minuses of the “issuer pays” model of credit ratings. The current model helps solve two information problems simultaneously. First, it’s hard for financial intermediaries such as mutual funds and life insurance companies to assess all the different bonds that they might invest in. Second, it’s difficult for individuals who trust their money to these financial intermediaries to monitor the soundness of their portfolios. Well-understood ratings by an independent rater address both problems.

We compare the issuer-pays to alternative models, such as “investor pays” and government-sponsored ratings. We conclude that despite potential conflict of interest problems, the “issuer pays” produces a stronger and less biased signal for market participants. We look back at the 2008-2009 financial crisis and see that ratings were inversely correlated with 10-year default frequencies even in the disrupted residential mortgage-backed securities (RMB) and collateralized debt obligation (CDO) markets, just as they should be.

We also address the knotty question of “procyclicality”—whether the rating agencies are too lenient in good times and then compensate by being too tough when the credit market turns down. We look at the recent evidence and suggest that there’s no reason to believe that the alternative business models do a better job than the “issuer pays” model in generating useful information in downturns.

We then set the business model and practices of the credit rating agencies in a broader context. In every part of the economy, the Information Age has made an exponentially increasing amount of data available to everyone. The difficult problem is extracting useful signals from the noise, especially when some market participants are actively taking advantage of opportunities to manipulate data, or to create false signals.

The credit ratings market, based on the issuer pays model, seems to have a way to consistently produce high quality and more accurate ratings that give strong and useful signals to market participants. Another benefit of independent credit rating agencies is that they set a global language – a global standard of comparison. This is especially important at times of stress, like now, when credit facilities need to be set up quickly.

Finally, we ask the important policy question of whether the “issuer pays” model provides any useful lessons for other areas of the economy struggling with extracting signal from noise, such as journalism and safety certification of new products.

BACKGROUND

Why do credit rating agencies exist? Whose interests do they serve? Bond issuers, from small companies to giants, sell a wide variety of fixed income securities. These are mostly bought by financial institutions such as banks, mutual funds, and insurance companies, who are functioning as financial intermediaries. For example, the 2019 financial accounts report from the Federal Reserve shows that out of the $14 trillion in corporate bonds, only $937 billion are held directly by U.S. households and nonprofits.2 That’s less than 7 percent. Households invest in corporate bonds indirectly, through financial intermediaries. They own shares in bond mutual funds, which in turn own corporate bonds. Or they have paid for life insurance, and the life insurance companies invest in turn in corporate bonds.

Here is a schematic diagram that shows the flow of money supporting the fixed income markets. The role of the credit rating agencies is to help solve not one but two information problems. First, financial intermediaries like mutual funds and life insurance companies want to have some way of assessing the riskiness of the bonds they are buying from the issuers.

Obviously they do their own analysis. But it’s also helpful to have an independent source of ratings, since the issuer has an incentive to minimize potential risks.

In theory, financial intermediaries could do without the ratings agencies, if they are willing to put enough money into analyzing every bond. However, fully shifting the bond riskiness assessment to the financial intermediaries wouldn’t solve and might even worsen the second information problem: The financial intermediaries buying the bonds have an incentive to understate the riskiness of their portfolio for households, other investors and regulators. Moreover, households and regulators generally do not have the resources to independently assess the riskiness of the portfolios of the financial intermediaries. Most households and retail investors, of course, are not direct users of credit ratings. But indirectly ratings provide guardrails for financial intermediaries such as life insurance companies, guiding which bonds they can invest in and reassuring buyers of life insurance policies that their money will be safe.

In effect, the ratings do double duty. They are used by the bond buyers to assess the riskiness of the bonds. In addition, they are used by households and regulators to assess the riskiness of the portfolios of the financial intermediaries as well. Any alternative to the current business model has to take into account both uses. (Figure 2).

HOW THE RATING PROCESS WORKS

Under the current model, the issuer of a bond pays the rating agency or agencies for the initial rating of a security, as well as ongoing ratings. Different rating agencies use different lettering schemes, but there is widespread agreement about what counts as investment grade bonds and what counts as speculative grade.

More precisely, the rating is an assessment that the bond can withstand a particular level of economic stress. For example, S&P lays out a chart that says that a AAA-rated bond can withstand a downturn on the level of the 1929 Great Depression.3

Unfortunately, no one, including the credit rating agencies, can forecast how deep the pandemic-related economic downturn can go.

As it heads into 1929 territory, it’s possible that some top-rated corporate bonds may default. Even under less stressful circumstances, the rating agencies cannot predict how the global economy or financial markets will perform.

Moreover, we can reasonably expect sectorspecific shocks that affect bonds in one sector differentially. For example, the current coronavirus crisis has the potential to cause significant downgrades of bonds issued by travel companies such as airlines and hotels. Meanwhile residential mortgage-backed bonds got hit hard during the 2008-09 financial crisis.

Given the unpredictability of the financial markets and the economy, the rating agencies can reasonably be expected to assess relative riskiness within a sector.

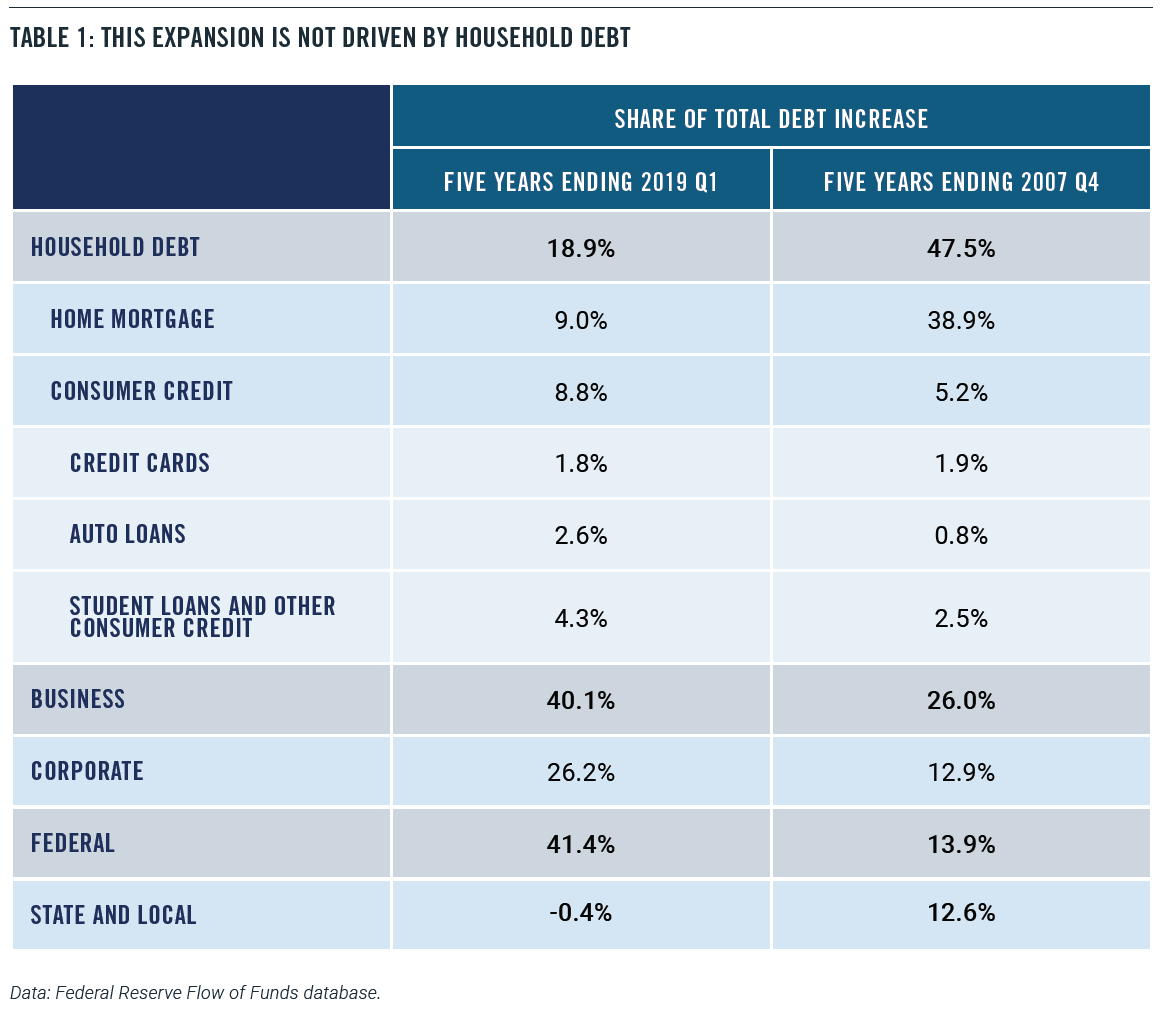

Table 2 is based on the performance summaries that the credit rating agencies are required to supply to the SEC annually. We looked at the tenyear period starting with 2006, the year before the financial crisis started, and focused on the performance of ratings issued for the RMB and CDO markets. These are two of the sectors that were disrupted the most in the 2008-09 financial crisis. We combined the data for Moody’s and S&P Global.4,5

We see that for these two important sectors, the rating on a security in 2006 is inversely correlated with the frequency of defaults 10 years later. The higher the initial rating, the lower the frequency of defaults.

THE FINANCIAL CRISIS OF 2008-09

Under the current model, the issuer of a bond pays the rating agency or agencies for the initial rating of a security, as well as ongoing ratings. Different rating agencies use different lettering schemes, but there is widespread agreement about what counts as investment grade bonds and what counts as speculative grade.6

In response, the Dodd-Frank Act of 2010 called for the SEC to study alternatives to the “issuer pays” business model, as well as other regulatory reforms. In addition, the Department of Justice, in combination with some state attorneys general, launched lawsuits accusing S&P and Moody’s, in particular, of defrauding investors.

The lawsuit against S&P was settled in 2015, focusing on a small number of incidents where internal procedures weren’t followed.7 A similar lawsuit against Moody’s was settled in 2017, with the rating agency agreeing to do a better job following its published rating procedures.8 In neither case was there sufficient evidence for a finding of fraud.

POTENTIAL BIAS

The obvious bias in the issuer pays model is that the ratings agencies compete to offer issuers better ratings. To put it another way, an issuer can engage in “ratings shopping” by choosing to pay the agency that offers the higher rating.

But study after study has shown much less evidence of rating shopping than one might expect. Most bond buyers only want to invest in securities that are rated by multiple agencies. That means rating agencies are under less pressure to boost ratings.

It is true that among single-rated securities or tranches, there is evidence that bond issuers are choosing the agency that offers the higher rating, as one might expect. One study found that for mortgage backed securities, “outside of AAA, realized losses were much higher on single-rated tranches than on those with multiple ratings, and yields predict future losses for single-rated tranches but not for multi-rated ones.”9

However, it turns out that bond buyers are not stupid. When they see a single-rated security, they are less likely to trust the rating than if it has been rated by multiple rating agencies. One 2019 study found that “bonds with upwardbiased ratings are more likely to be downgraded and default, but investors account for this bias and demand higher yields when buying these bonds.”10

In other words, the combination of the rating and the number of raters—both publicly observable pieces of data—produces useful information for participants in the bond market. In other words, the bias is partly self-correcting.

MITIGATING THE BIAS

Still, it is clear that credit rating agencies face conflicts of interests, much like other participants in financial markets. Accounting auditors face pressure to give good grades to their clients. Investment banks face pressure to overstate the potential of the initial public offerings that they help bring to market. And even regulators face conflicts of interest, since a typical career path often leads out of government to the regulated industry.

Like these other institutions, internal controls at the rating agencies can help mitigate the bias towards higher ratings. That includes internal separation of sales and analysis, so that the people assigning a rating to a bond are not in direct contact with the issuer of the bond. In addition to internal controls, credit rating agencies are heavily regulated around the world. That includes annual exams in the U.S. by a regulator who has significant authority to take action if any violations occur—including revoking a credit rating agency’s license to operate.

Even with these internal controls, though, the real mitigating institutions are transparency and reputation.

Transparency

The agencies assess the creditworthiness of the bonds according to published and detailed methodologies.11 In fact, there is literally nowhere else in the private sector that gives this level of transparency into the intellectual property of an organization, or that so rigorously documents their internal methodology for making decisions (imagine a newspaper committing itself publicly for how it chooses stories or does reporting, including reporting on advertisers). From the perspective of users of the ratings, the public nature of the ratings methodologies is essential. On transparency, one of the key benefits of an issuer-pays system is the fact that allows ratings to be released publicly – meaning they’re scrutinized every day by all corners of the market, the media, and academia. The ratings agencies cannot be judged on the performance of the ratings they issue, because of the uncertain effects of future events. But they can be judged on whether they follow their published methodologies.

Reputation

The other institution that mitigates bias is the need to preserve reputation. Credit rating agencies know that credit booms always end in a recession or credit crisis. The exact nature of the crisis can’t be predicted—the concept of a global pandemic, even if acknowledged within the realm of possibility, was part of very few reasonable scenarios. But when the crisis comes, credit rating agencies can be sure that their rating decisions will be challenged ex poste.

Their initial rating decisions will be criticized for being excessively sanguine. Their ratings downgrades will be attacked for either being too slow (leading to investors being misled) or too rapid (potentially undermining the economic viability of a bond issuer). All of their internal decision-making processes will be scrutinized and investigated.

This sort of intense scrutiny is only reasonable. Rating agencies do all of their work out in the open. They issue public ratings, and the performance of the ratings is visible as well. It’s not possible to investigate all of the bond issuers, so the ratings agencies are a proxy. They are an easy target, and that’s a good thing.

One can think of this as a long-term equilibrium where the rating agencies make good profits during the boom periods assigning ratings.

During the downturn it’s revealed how well their ratings performed. In addition, after the inevitable investigations, the rating agencies can expect that their internal rating process will be revealed as well. They therefore have a strong incentive not to cut corners and preserve their reputation so that they can survive the investigations of the downturns.

Indeed, issuers will not use the ratings if investors don’t trust in their independence and the strength of the models. In fact, demand for the use of certain credit rating agencies comes from the performance of their ratings over time and the ongoing judgment of investors.

ALTERNATIVE COMPENSATION MODELS

Is there a better way? Dodd-Frank charged the SEC with examining alternative business models for ratings agencies, since issuer pays has an obvious conflict of interest. Meeting in late 2019 and early 2020, the SEC’s Fixed Income Market Structure Advisory Committee looked at the question, in the words of SEC Chairman Jay Clayton: “Are there alternative payment models that would better align the interests of rating agencies with investors?”12

Economists, regulators, and financial market participants have suggested a variety of alternative compensation models designed to reduce conflicts of interest while still maintaining the critical function of the ratings agencies. A 2012 report from the GAO identified seven possibilities, though several had never been tried in the real world. At the end of the day, the only plausible alternatives are some form of “investor pays” and random assignment.

Investor Pays

One option is to require the investor to pay for ratings, like a subscriber fee. More precisely, it’s better to say that “financial intermediaries pay” since financial intermediaries such as mutual funds, pensions, and life insurance companies own the majority of fixed income securities.

The shift to “financial intermediaries pay” removes one conflict of interest, at the cost of creating two more. On the one hand, at the time of issue, it’s better for the bond buyer if the rating is cautious, so that the bond will be priced lower and pays a higher yield. On the other hand, financial intermediaries prefer that the rating agencies are slow to downgrade, to make their portfolios look better to final investors and regulators.

It’s also true that there are fewer financial intermediaries than bond issuers. Moreover, financial intermediaries tend to have the resources to do their own analysis if needed. They are therefore less dependent on the rating agencies, and have less need for the information.

In the end, there is no compelling case that the “investor pays” model is superior to the “issuer pays” model. Moreover, it’s hard to see how an “investor pays” model would work without strict government rules.

Random assignment

The critics who worry about issuers shopping for ratings keep coming back to the same solution: Random assignment of rating agencies to new bond offerings. When an issuer wanted to have a bond rated, they would apply to a central organization that would randomly assign a credit rating agency off of a list of approved agencies. The agency would then get paid for its work at a fixed rate.

In effect, the “random assignment” compensation model turns credit ratings into a government-run utility using “fixed price” contractors. As with all government-run utilities, there would be pluses and minuses.

On the one hand, random assignment reduces or eliminates the ability of issuers to shop for better ratings, which is the intention. That means rating agencies would not have an incentive to artificially boost ratings.

But as in the case of “investor pays,” eliminating one problem creates two new problems. First, under the random assignment compensation model, rating agencies have no incentive to put effort into producing high quality ratings, since they get picked randomly even if they do just an average job. Credit rating agencies would be investing the money in innovation. As a result, the random assignment approach may produce ratings that are less biased but also less accurate. Moreover, there might be an incentive to set ratings artificially low to avoid downgrades.

The second and related problem is deciding which rating agencies are on the approved rotation list—which ones are eligible, and which ones need to be removed for bad performance. That requires a government “gatekeeper” to assess the short-term and long-term performance of each agency and which ones are “good enough” to be on the list.

There are two approaches to assessing performance of rating agencies. One is to look at measurable outcomes—for example, the frequency of defaults and large downgrades. These must be measured over an entire credit cycle, so it’s tough to see how they can be applied in the short run. Moreover, any “objective” measure will be gamed by new rating agencies that want to get on the list.

The other approach is to set up a standard that is based on minimum capabilities. That is, the government gatekeeper would add to the list any rating agency that has enough licensed analysts and published methodologies. The result is that more competition is likely to lead to worse quality ratings.

There’s one final important point. One of the biggest and most politically fraught rating decisions is how to assess sovereign debt, and in particular the debt offerings of the U.S. government. With the government as the gatekeeper for the random assignment list, there’s likely to be pressure on rating agencies not to downgrade government debt even if appropriate. The conclusion is that the shift to a random assignment system is likely to produce new unknown biases in ratings.

PROCYCLICALITY

One charge levelled against the current “issuer pays” model is that it leads to “procyclicality.” If ratings were procyclical, that would mean that the rating agencies go too easy on issuers in good times, and then are forced to be tough and downgrade bonds in bad times. In this way, say the critics, ratings procyclicality can end up making the booms bigger and the downturns worse.

However, the evidence for ratings procyclicality is, to put it mildly, mixed. A July 2020 report from the SEC observed that “ratings downgrades are generally lagging indicators of cost of debt capital. Moreover, consider the issue of whether rating agencies have been giving “too high” ratings to corporate borrowers in recent years. In a February 2020 report, the OECD directly addressed that question, comparing the pattern of ratings by one credit rating agency in 2017 with 2007. The report found that at the same rating level, borrowers in 2017 had a higher level of debt relative to various measures of cash flow and earnings.

By itself, that result suggests that credit rate standards had gotten easier in 2017 compared to 2007. However, the report then admits that low interest rates made it easier for corporate borrowers to cover their debt payments in 2017 compared to 2007, providing evidence that credit standards had not gotten easier.

In truth, the procyclicality argument is a bit of a red herring. When the credit cycle turns down, credit rating agencies are stuck no matter what they do. If they are conservative and cautious about downgrading bonds, they are accused of protecting their issuers. If they downgrade aggressively, they are accused of making the recession worse. The cries are especially loud when sovereign debt issued by governments is downgraded, since such a move has a broad effect on the ability of governments to raise money.

Moreover, there’s no evidence that the alternative compensation models would do any better. Under the “investor pays” model, the rating agencies will come under strong pressure from investors to not downgrade the bonds in their portfolios in downturns, making ratings untrustworthy at precisely the moment they are needed the most. And as we point out in the previous section, under the “random assignment” model, any rating agency that downgraded the government might find itself out of the rotation in the future.

OTHER APPLICATIONS OF ISSUER PAYS

For all their flaws, independent credit ratings agencies, paid by issuers, produce a strong and useful signal in a noisy information environment. It isn’t perfect, but the ratings perform well, and users are able to adjust for potential conflicts of interest. The combination of transparency and reputation seem to create sufficient incentives to make it worthwhile for the credit rating agencies to take their job seriously and produce information that issuers, financial intermediaries, and households and regulators can’t do without.

In the broader sense, one gets a sense that the current “issuer pays” credit rating system is actually a pretty decent way of solving a difficult problem that occurs across the economy—certifying the quality of products and services. An independent third party is paid by the producer or manufacturer of the product or service to do the certification (“issuer pays”). One key is that the payment has to be large enough that the certifying organization has an incentive to maintain their reputation.

Certification of electric equipment

Indeed, the “issuer pays” model turns out to be applicable to other areas of the economy where information is important. For example, certification of electrical equipment and other products for safety is an area that is increasingly important these days. The top U.S. “certification agency” is UL LLC, an organization founded in 1894 as the Underwriters’ Electrical Bureau, and operated until 2012 as the non-profit Underwriters Laboratory.13

UL’s business model is to charge companies with new products to get certification for meeting safety standards, typically promulgated by Underwriters Laboratory, in order to get the UL certification. There are other certification organizations in the United States, such as Intertek Testing Services NA, Inc., based in Illinois. But UL is the leader.

For many products, there’s no legal requirement to have a UL certification, but many larger retailers won’t sell the product without. Certification for products used in the workplace is mandated by OSHA, which publishes a list of approved testing laboratories.14 In addition, the government sometimes mandates that particular products cannot be sold in the United States without UL certification. That was true in 2016 for hover boards, for example, when the CPSC banned any hover board that didn’t have a UL certification.15

As with credit rating agencies, issues regularly arise about the objectivity of UL certification.16 Moreover, as UL has extended its work to certify a wider variety of products, questions have arisen about its capabilities. Nevertheless, the “issuer pays” model in product safety certification seems to be functioning well.

Indeed, the European Union, which on the surface uses a “self-certification” model, seems to be heading towards “issuer pays.” The selfcertification model uses the CE mark, which means that the manufacturer or retailer is taking responsibility that the product meets EU standards.17 But in many product areas the company must also get the approval of what’s known as a “notified body,” which is the equivalent of a certifying authority.18

Unfortunately, the European system has been criticized for being too lax.19 Gradually they have been moving closer to a pure “issuer pays” model, with more products requiring certification by notified bodies.

Rating of journalist organizations

One area where third-party rating is just getting started is the news business. Companies such as Facebook and Twitter have been criticized for allowing too much ”fake news” on their platform—low quality news sources that spread misinformation. On the other hand, if they start exercising too much control, they are accused of censorship and monopoly power.

The obvious solution is for the platforms to use an independent third party. Indeed, we’ve started to see a rise of for-profit companies that rate the reliability of news sources. The leading one so far is NewsGuard Technologies, founded in 2018 by Steven Brill and Gordon Crovitz, formerly publisher of the Wall Street Journal. NewsGuard ranks news sources on nine different criteria, such as “avoids deceptive headlines” and “does not repeatedly publish false content.” 20

The demand for journalistic ratings comes in part from the threat of government regulation. European countries, in particular, have passed laws to control “fake news.”21 Companies such as Facebook, Google, Microsoft, Mozilla, and Twitter have signed onto the European Commission’s voluntary Code of Practice on Disinformation, which commits them to take certain steps to control fake news.22

So far, the NewsGuard business model is “user pays.” As the company says, “NewsGuard’s revenue comes from Internet Service Providers, browsers, search engines and social platforms paying to use NewsGuard’s ratings.” For example, Microsoft is paying a licensing fee to NewsGuard to incorporate the ratings into Microsoft’s Edge browser.23 In addition, individuals can subscribe to the service for a small monthly fee. It’s not clear how many other platforms are paying, especially since the ratings are publicly available.

Over time, platforms may gravitate towards only featuring news sources that get satisfactory grades from at least two independent raters. That opens the possibility of an “issuer pays” model where news sites pay a fee to get rated, perhaps proportional to their web traffic. This has the advantage that the ratings are public and available to everyone.

CONCLUSION

Since the 2008-2009 financial crisis, critics have worried about the biases built into the “issuer pays” compensation model for credit ratings agencies. Now that the Covid-19 crisis has placed the credit markets under great stress, these questions are once again coming to the fore. But as we show in this report, nobody has been able to come up an alternative compensation model that is clearly better. There’s no reason to believe that the issuer pays compensation model will get in the way of the necessary effective and independent third party assessment of default probabilities under extreme uncertainty.

Indeed, in the Information Age, the “issuer pays” approach for credit ratings may serve as a good model for other parts of the economy, because it generates a clear signal. We identified another sector, product certification, where “issuer pays” is the dominant model despite its inherent biases. We also consider whether the “issuer pays” model could be applied to certify the quality of journalist organizations, an exceptionally important problem that has been difficult to solve.