Policymakers across the United States are struggling to figure out how to adapt to swift changes in the American workforce. So-called “alternative work arrangements,” for example, are growing: in 2015, 15.8 percent of workers were independent contractors, temporary workers, contracted workers, or “gig” workers—a 50 percent increase in just a decade. Yet some efforts at adaptation—such as expansion of the “joint employer” doctrine—may do more harm than good. PPI is committed to helping find solutions that balance worker protection with business productivity and investment and the expansion of the joint employer doctrine fails to strike that balance. We must figure out a better way forward that boosts economic dynamism without sacrificing worker interests.

At the end of July, the Save Local Business Act was introduced into the House of Representatives. The bill, with three Democratic cosponsors among over three dozen Republicans, aims to narrow the expanded definition of “joint employer” promulgated by the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) in 2015. This elicited immediate praise from business groups—particularly those associated with franchises—and opposition from unions and other groups advocating for worker rights.

The joint employer doctrine is used by the NLRB and courts in determining legal responsibility for issues such as overtime pay when more than one employer is involved. If a bank, for example, contracts with a company to provide janitors to clean the bank facilities, the janitors are employees of the contract firm, not the bank. Yet, if the bank has some level of control over of the janitors’ wages and hours, it could be deemed a “joint employer” and would be responsible for appropriate legal compliance.

Not incidentally, the joint employer doctrine is central in shaping the ability of employees to engage in collective bargaining. Contract workers, temporary workers, and franchise employees—all of whom are affected by the joint employer doctrine—are difficult to unionize. Employees of franchise locations—fast-food restaurants, for example—are technically employees of the franchisee (the local operator), not the franchisor (the national brand). The entire purpose of the franchising model is to allow the franchisor to focus on brand and system, and leave the franchisee to focus on operations and local context, including employment.

Under the expanded joint employer doctrine of the NLRB, however, it is possible that both the franchisee and the franchisor could be considered employers of the workers at each individual franchise location. This “could fundamentally change business in the United States by destroying the franchise model.”

Until the 1980s, the NLRB threshold for a joint employer finding was “direct or indirect control” over working conditions. This was a fairly broad doctrine and, in certain circumstances, could be used to find that employees were subject to “control” by more than one employer. Nonetheless, the NLRB joint employer standard remained more modest than definitions used in Title VII of the Civil Rights Act and the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA).

Beginning in the 1980s, the NLRB gradually narrowed the definition to “direct and immediate” control over employment issues. The change from “indirect” to “immediate” had large implications in where the joint-employer line was drawn. If the bank “shares or codetermines” the conditions of employment of the contracted janitors, and “meaningfully affects” their hiring, firing, supervision, etc., the company could be a joint employer. Now, the NLRB says, no longer is “direct and immediate control” required—even the possession of authority to direct third-party employees is sufficient, regardless of whether the authority is exercised.

These subtleties in language and reliance on factual findings are classic examples of legalese, but cases involving worker rights and business interests frequently turn on choice of words and how those words are put into practice.

Business groups do not welcome a broader definition. Especially as it pertains to franchise arrangements, the more expansive standard could open up franchisors to greater liability and more attempts at collective bargaining. Already, we have seen arguments to apply the extended joint employer doctrine to other areas, such as student athletes. A challenge to the NLRB’s expansive interpretation is currently pending in front of the D.C. Circuit, and it is expected that the NLRB under President Trump will work to narrow the standard. In the Republican-controlled Congress, the Save Local Business Act could find easy passage and, at the state level, legislatures are being lobbied to pass laws saying that franchisors cannot be considered joint employers.

One problem is the likely response from franchisors to the expanded NLRB standard—in particular, we may see reduced business dynamism. Franchising is an engine of entrepreneurship in the United States, with independent operators who, despite the assistance of national brands, assume plenty of financial risk themselves. At the same time, we have seen the rise of large franchising operations that own hundreds of franchises across the country. Not surprisingly, large franchising operations are better able to comply with employment laws than small, single-operator franchisees. Faced with the new incentive structure of the expanded joint employer doctrine, franchisors will have a clear preference against smaller franchisees in favor of the larger organizations. This will make it much harder for new entrepreneurs to enter business through franchising, further raising barriers of entry for business creation.

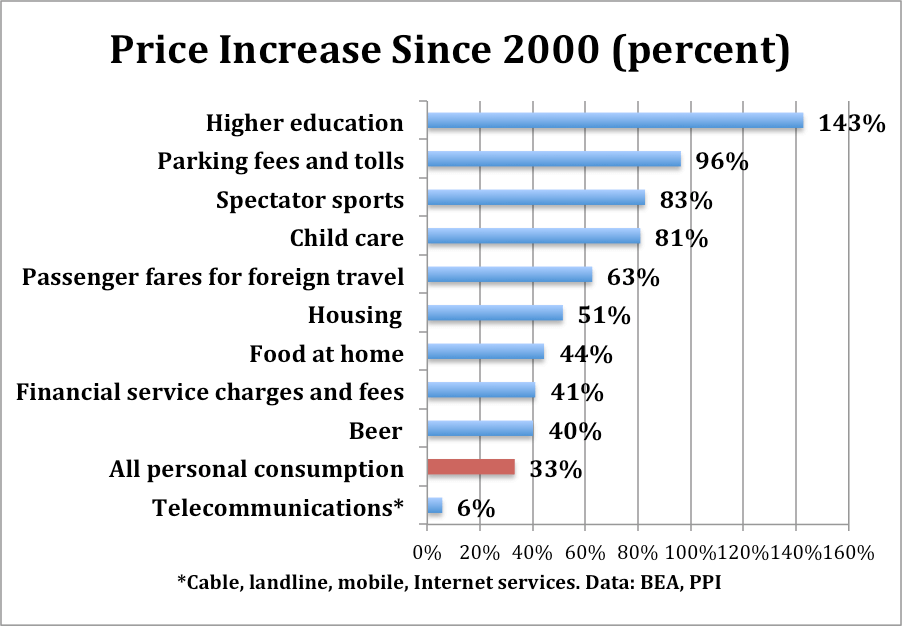

The NLRB and other public agencies have the unenviable task of modifying law and policy to keep up with shifting employment arrangements, in an environment of stagnant wages for many workers, geographic concentration of economic rewards, and concerns about entire occupational categories being lost to automation. As mentioned, “alternative work” is growing. The Government Accountability Office (GAO) estimates that the “contingent workforce,” depending on the definitions used, could be anywhere from five to 40 percent of the total labor force. More people are receiving income from multiple sources, which includes new online and on-demand platforms. These changes have prompted calls for new legal classifications, such as the “independent worker” category proposed by the Hamilton Project two years ago.

Confronted with these challenges, expanding the joint employer doctrine is perhaps an understandable attempt to try to help workers cope. The fastest-growing type of alternative work arrangements is “workers provided by contract firms,” precisely those at the core of the joint employer doctrine. Yet we also need to help policymakers and businesses think creatively about other ways to manage and adapt to these challenges, as they will only increase in significance. In the face of a “fissured workplace,” how can policymakers help workers and businesses adapt and succeed together?

In managing these changes, we must ensure adequate worker protection and representation while also supporting (or at least not hindering) businesses to pursue innovation and productivity. Policymaking should be guided by certain principles, among which might be the following.

- Clarity and certainty. Any standard leaves room for interpretation (and litigation), but workers and firms need to have clear ideas about where they stand regarding rights and responsibilities.

- Get the incentives right. Policies should minimize the amount of “gaming” that might go on by firms in trying to avoid legal compliance. This doesn’t mean the presumption should be that all firms will act badly—policymakers need to pay attention to the incentives they establish.

- New ways for workers to organize and improve. Despite the NLRB’s presumption, traditional unions may not be the best adaptive form of organizing in the modern workplace, and new Internet platforms have arisen to help fill the gap. Policy should facilitate these, but also focus on how new organizing tools can support learning and skill upgrading among workers, not just collective bargaining.

- Informational equity and transparency. As the Roosevelt Institute has coherently outlined, employees in more sectors are subject to “opaque algorithms” that determine wages, scheduling, evaluation, and so on. Giving workers more transparency and control over this information will reduce asymmetry and empower workers to better manage their careers.

Most of the American labor force is still characterized by traditional employment, but new forms of work are growing rapidly, especially in sectors where low-wage and high-turnover work predominates. Addressing this challenge is a major priority, and we need to find ways that policy can jointly advance the interests of workers and firms.