President Obama issued an executive order yesterday to expand Pay As You Earn (PAYE), the administration’s flagship income-based student loan repayment program. The president’s action offers millions of workers welcome if modest relief from student debt burdens. But progressives should hold their applause, because it also has two downsides.

First, expanding PAYE boosts government public subsidies for a broken higher-education financing model. Second, it will reinforce the already strong bias in public policy toward college attendance at the expense of other post-secondary options for young Americans.

Unlike the standard student-loan repayment program, which has fixed repayment schedules, PAYE is an income-driven repayment program, meaning that how much you pay is based on how much you earn. Eligible borrowers repay up to 10 percent of their monthly income, with any remaining balance forgiven after 20 years. Its commendable goal is to make repayment easier for graduates who take important jobs that pay less — social workers, school teachers, workers in the nonprofit sector.

With the new order, PAYE eligibility will expand to an additional 5 million people who borrowed before the original October 2011 cutoff. It follows last year’s campaign to dramatically increase PAYE enrollment, during which the Department of Education contacted 3.5 million eligible borrowers with limited success. Legal questions surrounding the new order have already been raised regarding presidential authority, especially since the cost to the government remains unknown.

In expanding PAYE, Obama underscored his desire to assure affordable access to college. The idea that college is for everyone rests on the well-established fact that college graduates earn more money than high school graduates on average.

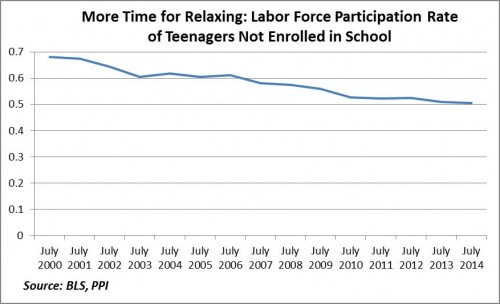

But as I’ve recently argued, while some form of post-secondary education is necessary, not everyone needs a bachelor’s degree. The point was even made recently by Secretary of Labor Thomas Perez.

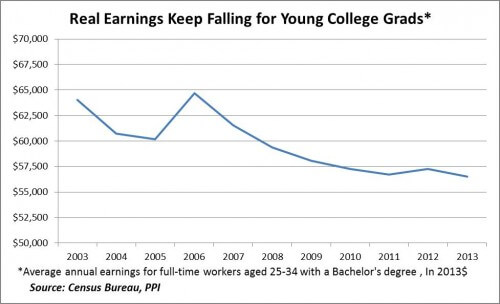

The wage premium for college graduates is growing not because the degree is worth so much more, but because high school diplomas as worth so much less. In fact, real earnings for recent college graduates have been falling over the last decade, and underemployment remains at record highs. New research shows the number of college graduates taking white-collar jobs declined since 2000, and is now at 1990 levels. If wage growth for recent college graduates was in line with tuition increases, today’s conversation surrounding college affordability would look very different.

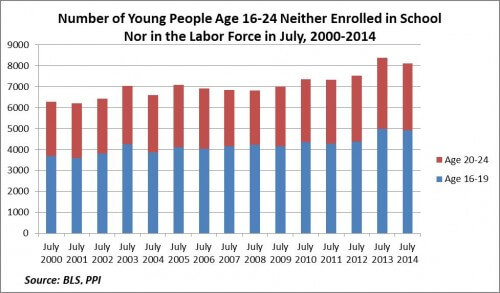

Moreover, the new tools of digital learning — such as online courses — should be driving education costs down, yet tuition continues to climb. That suggests the entire financing model for higher education needs reform. And because there are too few viable pathways into the workforce after high school, our $100 billion per year federal student aid system is channeling people into four-year colleges who may be better suited for less expensive options.

Expanding PAYE may relieve the financial strain on borrowers in the short term, but it will almost certainly exacerbate the burden on the federal student aid system in the long run. With PAYE, increased access and opportunity for students comes at the cost of accountability for educational institutions. Borrowers have less incentive to make smart borrowing decisions, or complete in a timely manner. And schools have less incentive to control costs.

When income-based repayment was first introduced in 1993, then called “pay-as-you-can,” it was to encourage “public service” jobs — those jobs earning a relatively modest income. But the idea was not for everyone to enroll in such a plan, only those who needed longer repayment terms to avoid default. Then, in a debate remarkably similar to today, President Clinton acknowledged that the longer terms under income-based repayment were not ideal for most borrowers, and in fact the standard 10-year repayment plan worked well for the majority.

Still, if PAYE expansion goes forward, there are ways to keep its costs in check. First, expand PAYE only to undergraduate loans. If the main intention is to promote college affordability, then it makes sense to focus on undergraduates. Graduate school borrowers, who tend to have higher levels of debt, could apply annually instead of being automatically eligible.

Second, schools should give borrowers the information they need to make an informed decision about which plan is the best for them, and have the Department of Education regularly report on program metrics. Finally, limit, if not eliminate, the provision for “public service” that forgives any remaining balance after 10 years. With the income-based benefits already provided by PAYE, this provision becomes a second subsidy for the same loan.

The president’s executive order could be interpreted as a way of compensating young college graduates for the slow-growth economy they graduated into. Yet while such compassion is admirable, the administration also needs to grapple with the root causes of soaring college costs, including the dearth of pathways into the workforce for young Americans who may not need a four-year bachelor’s degree.

This op-ed is originally appeared in The Hill, find their posting here.