Growth should be at the centre of the social democratic agenda. Raising levels of economic security and equality are important goals, but it’s economic growth and innovation that allow high living standards and generous welfare states to be a reality

The “5-75-20” essay covers a lot of territory and offers centre-left parties many sensible governing ideas. In the end, though, this pudding lacks a theme – a convincing idea for how progressives can capture the high ground of prosperity.

The essay does prescribe something called “predistributive reform and multi-level governance,” but it’s hard to imagine rallying actual voters behind such turgid abstractions. I doubt Orwell would have approved of a word like “predistribution,” which clearly has an ideological agenda, even if the agenda itself isn’t so clear.

The term seems to promise a political response to inequality that doesn’t involve more top-down redistribution, which makes middle class taxpayers queasy. What it means in practice, however, is vague. Beyond essential public investments, do governments really know how to manipulate markets to produce more equal outcomes?

Before we go down this murky trail, let’s ask ourselves: Are we responding to the right problem? As Europe and America emerge slowly from a painful economic crisis, what is the main demand our publics are making on progressive parties? In the United States, anyway, the answer is: create jobs and resuscitate the economy. Since 2008, voters have consistently ranked growth as their overriding priority.

I can’t speak for Europeans; perhaps they are more concerned about inequality or sovereign debt or immigration or climate change. There’s no doubt, however, that Europe’s recent economic performance has been even worse than America’s. Both suffer from what the economists call “secular stagnation” – slow growth in plain language.

According to the OECD, average GDP growth across the EU was a scant 0.1 percent last year, compared to 1.8 percent in the United States. Unemployment averaged nearly 12 percent in the eurozone, versus 7.3 percent here (it’s now down to 6.3 percent, though U.S. work participation rates have plummeted). For young people, the job outlook is catastrophic: 16 percent of young Americans were out of work; 24 percent in France, 35 percent in Italy, and 53 percent in Spain. Only Germany (8.1 percent) among the major countries is doing a decent job of making room in its economy for young workers.

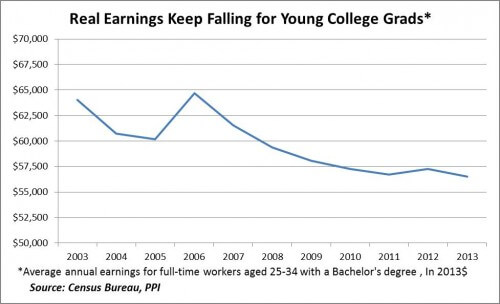

Progressives have yet to furnish compelling answers to anemic growth, vanishing middle-income jobs, meagre income gains for all but the top five percent, and social immobility for everyone else. Such conditions have radicalised politics on both sides of the Atlantic, sparking the tea party revolt in America and helping populist and nationalist parties make unprecedented gains in the recent EU elections. Populist anger over unfettered immigration, globalisation, and the centralising schemes of elites in Washington and Brussels has surely been magnified by pervasive economic anxiety.

The essay argues plausibly that the “new landscape of distributional conflicts and deepening insecurity” gives progressives a chance to channel voters’ frustrations in more constructive directions. It calls for new welfare state policies to win over the “new insecure,” the 75 percent who are neither the clear winners or losers of globalisation. But it says surprising little – and not until the last bullet ‒ about how progressives can boost productive investment, encourage innovation and put the spurs to economic growth.

This is emblematic of the centre-left’s dilemma. Our heart tells us to stoke public outrage against growing disparities of income and wealth and rail against a new plutocracy. Our head tells us that social justice is a hollow promise without a healthy economy, and that a message of class grievance offers little to the aspiring middle class.

What progressives need now is a politics that fuses head and heart, growth and equity, in a new blueprint for shared prosperity. But some influential voices are telling us, in effect, to give up on economic growth.

Lugging a 700-page tome called Capital in the Twenty-First Century, the French economist Thomas Piketty has taken the US left by storm. In advanced countries, he says, “there is ample reason to believe that the growth rate will not exceed 1-1.5 percent in the long run, no matter what economic policies are adopted.” What’s more, growing inequality is baked into the structure of post-industrial capitalism, and is likewise impervious to policy.

Some progressive US economists, such as Stephen Rose and Gary Burtless, have challenged the empirical basis of Piketty’s gloomy prognostications. According to Capital, middle-class incomes in the United States grew only three percent between 1979 and 2010. But the Congressional Budget Office, using data sets that take into account, as Piketty does not, the effects of progressive taxation and government transfers, found that family incomes rose by 35 percent during this period. That’s not a trivial difference.

Still, no one on the centre-left denies that economic inequality has grown worse in America, and that it demands a vigorous response. But progressives ought to be wary of deterministic claims that the United States and Europe have reached the “end of affluence” and must content themselves with sluggish growth in perpetuity.

Nor can anyone be certain that a return to more robust rates of growth would merely reinforce today’s widening income gaps. That’s not what happened the last time America enjoyed a sustained bout of healthy growth, on President Clinton’s watch. Let’s take a look back at what happened in the bad, old neoliberal ‘90s.

During Clinton’s two terms, the US economy created nearly 23 million new jobs. Over the latter part of the decade, GDP growth averaged four percent a year. Tight labour markets sucked in workers at all skill levels. Unemployment fell from 14.2 percent to 7.6 percent, and jobless rates for blacks and Hispanics reached all-time lows. The welfare rolls (public assistance for the very poor) were cut nearly in half, while about 7.7 million people climbed out of poverty. Military spending declined, the federal bureaucracy shrank, the IT and Internet revolution took off, trade expanded and Washington even managed to run budget surpluses.

Not too shabby, but how were the fruits of growth divided? The rich did very well, but few seemed to mind because everyone else made progress too. Median income grew by 17 percent in the Clinton years. Average real family income rose across-the-board, and actually rose faster for the bottom than the top 20 percent (23.6 vs. 20.4 percent.) This was genuine, broadly shared prosperity, and it’s not ancient history.

Now, it may well be that a new growth spurt won’t immediately narrow wealth and income gaps. But a sustained economic expansion would make it easier to finance strategic public investments in modern transport and energy infrastructure, in science and technological innovation, and in education and career skills. It would help progressives avoid drastic cuts in social welfare and maintain decent health and retirement benefits for our ageing populations. And, it would allow for a gradual winding down of oppressive public debts.

Nonetheless, many US progressives seem preoccupied instead by questions of distributional justice, economic security and climate change. They want to raise the minimum wage, tax the rich, close the gender pay gap, stop trade agreements, revive collective bargaining, slow down disruptive economic innovation, and keep America’s shale oil and gas bonanza “in the ground” to avert global warming. This agenda is catnip to liberals, green billionaires and Democratic client groups, but it won’t snap America out of its slow-growth funk. It energises true believers, but won’t help progressives appeal to moderate voters, who hold the balance of power in America’s sharply polarised politics.

Increasing economic security and equality are important goals, but it’s economic innovation and growth that makes high living standards and generous welfare states possible. Without them, the progressive project grows static and reactionary, rather than dynamic and hopeful. Progressives, after all, ought to embrace progress.

This articles forms part of a series of responses to the Policy Network essay The Politics of the 5-75-20 Society.