The number of large U.S. manufacturing facilities has dropped by more than a third since 2000, devastating many communities where factories were the lifeblood of the local economy.

One promising way to revive America’s manufacturing might is not by going big but by going small – and going local. Digitally-assisted manufacturing technologies, such as 3D printing, have the potential to launch a new generation of manufacturing startups producing customized, locally-designed goods in a way overseas mega-factories can’t match. To jumpstart this revolution, we need to provide local manufacturing entrepreneurs with access to the latest technologies to test out their ideas. The Grassroots Manufacturing Act would create federally-supported centers offering budding entrepreneurs and small and medium-sized firms access to the latest 3D printing and robotics equipment.

THE CHALLENGE: NEXT-GENERATION U.S. MANUFACTURING NEEDS A JUMPSTART.

The collapse in manufacturing employment and wages drove a stake through the heart of America. Conventional factories making commodity high-volume products could not compete with mega-sized plants in low-wage countries. That’s why many of America’s largest and most productive plants have closed or shrunk sharply since 2000, devastating many less dense areas where local factories were the main source of jobs.

Yet, for all the talk of an intangible data-driven economy, physical industries such as manufacturing and agriculture are still essential to prosperity – especially outside our largest cities. These are, however, precisely the industries where investment, incomes, and jobs have lagged behind, hurting millions of working Americans across the country.

U.S. manufacturing productivity is lagging.

One problem is that many small and medium-size factories have been stuck with old technologies and aging equipment because the owners don’t have the funds to modernize. As a result, productivity in U.S. factories has lagged, the price charged by domestic factories has risen, and the penetration of Chinese products into domestic markets has continued to increase. In 2017, imports from China, adjusted for inflation, rose by 9.4 percent. By comparison, the gross output of U.S. factories rose by only 2.2 percent.

Digitally-assisted manufacturing is the wave of the future, but investment in these technologies is also lagging.

Digitally-assisted manufacturing technologies are potentially game changers for U.S. manufacturing. Local factories using 3D printing, robotics, or similar advances could,for instance, produce customized and locally-designed products – better-fitting clothing, more-comfortable furniture, and customized equipment for businesses – at a price overseas mega-factories can’t match.

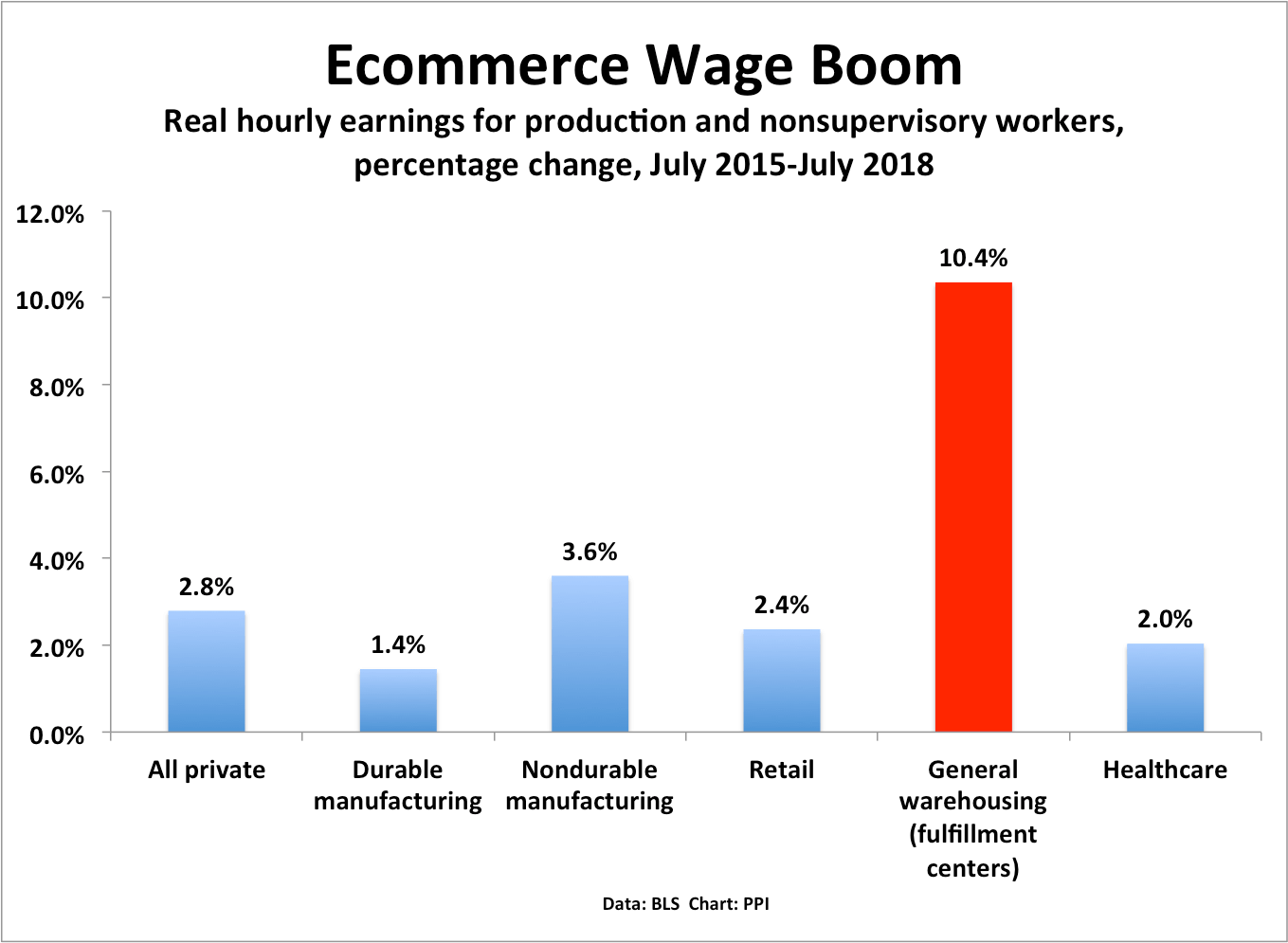

Moreover, there’s increasing evidence that digitization can open up new markets and create new jobs. Even the most automated technologies require loads of skilled workers to do the more complicated tasks machines can’t handle. Indeed, the newest term is “cobots” – collaborative robots designed to work with humans (rather than replace them).

Despite these potential rewards, however, the U.S. risks falling behind in this crucial race for next-generation manufacturing. The America Competes Act of 2010 authorized federal loan guarantees for small or medium-sized manufacturers for the use or production of innovative technologies. But no such loan guarantees have been issued.

The Manufacturing Extension Partnership is an excellent program, but its FY2018 funding of $140 million is 15 percent lower, in real terms, than its funding in 1998. The American Innovation and Competitiveness Act of 2017, signed in the last days of the Obama Administration, does offer limited funding for a couple of centers to explore automated manufacturing. However, that’s not enough for a country the size of the United States – not when Japan and Germany are putting much more money into pushing their manufacturing sectors into the future.

Now is the time to beef up our current support for local manufacturing entrepreneurs and create a new wave of digitally-assisted, high-wage manufacturing jobs around the country.

THE GOAL: CREATE 50,000 ADDITIONAL MANUFACTURING STARTUPS OVER THE NEXT FOUR YEARS USING DIGITALLY-ASSISTED TECHNOLOGIES – AND ONE MILLION NEW JOBS.

Digitally-assisted manufacturing technologies will boost productivity, cut costs, and increase flexibility. In the process, that will open up new markets for customized and semi-customized goods.

We advocate a national push to create 50,000 new manufacturing startups across the country to encourage the rebirth of American manufacturing ingenuity at the local level. If each startup employs 20 people, on average, that will mean one million new jobs. The goal is to get scale on new production technologies across the country – not just in one or two centers. We are not talking about industrial policy, or protectionism, or bringing back old and dying industries. Rather, the goal is to help accelerate the next wave of manufacturing prosperity.

THE PLAN: SEED THE CREATION OF STATE AND LOCAL DIGITAL MANUFACTURING CENTERS AND SUPPORT BUDDING MANUFACTURING ENTREPRENEURS.

We advocate a three-part program:

1. Increase access to technology.

It’s essential to provide local manufacturing entrepreneurs access to the latest technologies to test out their ideas. We propose a Manufacturing Grassroots Act that would offer state and local governments funds to set up centers with the latest 3D printing and robotics equipment – along with all the necessary software and training. Budding entrepreneurs and small businesses can apply for access on an “all-comers” basis, to give everyone an opportunity to get in on the ground floor of wealth creation.

2. Guarantee federal loans.

Existing small and medium-size manufacturers need help getting funding for the adoption of the new technologies. That means federal loan guarantees, based on the existing but unutilized program mentioned earlier from the 2010 America Competes Act. It may also mean setting up a new program for low-interest loans to manufacturers who want to digitize.

3. Fund federal research.

At the national level, Congress should budget $300 million to fund federal research to develop the underlying standards for online manufacturing platforms, just like the government developed the underlying standards for the Internet. This work is already going on, but it needs to be accelerated.

ENDNOTES

Michael Mandel, “The Rise of the Internet of Goods: A New Perspective on the Digital Future for Manufacturers,” Progressive Policy Institute and Manufacturers Alliance for Productivity and Innovation, August 2018.