PPI President Will Marshall and Ben Ritz from the Center for Funding America’s Future are joined by Congresswoman Sharice Davids (KS-3) and Congressman Scott Peters (CA-52) for a conversation on the fiscal health of the United States, budget priorities, the election, and their perspective on how America’s economy can return with a resilient recovery.

Category: Uncategorized

A vision for independent workers

A slice of bread is good, but a whole loaf is better. In the spring, Senator Mike Braun of Indiana introduced the Helping Gig Economy Workers Act to shield digital companies from lawsuits on worker classification when providing protective equipment during the coronavirus pandemic. This legal “safe harbor” for such digital companies could find its way into the Republican stimulus package under consideration in Congress.

But independent workers around the country, including freelancers and sole proprietors, need much more than protective equipment. They need access to a universal baseline level of benefits, paid for by the companies they work with, without losing the work flexibility they value. They need a new regulatory framework that is suited for the 21st century labor market rather than the 20th century labor market. Reaching these goals requires legislation, but it is very different from what Braun is proposing.

First, it is important to realize that while independent contractors receive tax deductions with expenses like vehicle miles, the tax system penalizes independent workers who provide their own benefits. Most independent workers must pay Social Security and Medicare taxes on the money they contribute to their retirement accounts. By contrast, the contribution of employers to their employee retirement accounts is exempt from these taxes, subject to certain rules. Indeed, this tax exemption can be worth thousands of dollars for middle income workers. Similar problems also arise with health insurance coverage for independent workers.

Second, the companies that do business with independent workers are not able to provide benefits because then the Internal Revenue Service would classify the workers as employees, leading to the loss of flexibility and control over their hours and who they can work for. Such a shift with status would likely reduce the number of available jobs. Those remaining workers would have fixed schedules, capped hours, and inability to work with more than one company. It is obvious that these tax and regulatory barriers weaken the labor market position of independent workers since benefits are more expensive and difficult for them to receive.

Read more here.

PODCAST: Conversation with Rep. Sharice Davids and Rep. Scott Peters

Listen on Breaker.

Listen on Google Podcasts.

Listen on Overcast.

Listen on Pocket Casts.

Listen on Radio Public.

Listen on Spotify.

PPI President Will Marshall and Ben Ritz from the Center for Funding America’s Future are joined by Congresswoman Sharice Davis (KS-3) and Congressman Scott Peters (CA-52) for a conversation on the fiscal health of the United States, priorities for the upcoming stimulus bill, the election, and their perspective on how America’s economy can return with a resilient recovery.

10 Myths About Big Tech & Antitrust

On Wednesday, the House Subcommittee on Antitrust will hear testimony from the CEOs of Amazon, Google, Facebook, and Apple. Throughout the long pandemic shutdown, Big Tech has supplied the products and services that allow many Americans to keep working remotely and to stay in touch with family and friends while socially distancing. Our connectedness is one of the few bright spots in this ordeal. It’s an odd moment for lawmakers to be expending energy on castigating America’s most innovative and globally competitive companies, simply because they are big.

However, critics of the tech giants have labeled them “monopolies” and increasingly advocate for regulators to break them up. With that in mind, here are 10 myths about Big Tech and antitrust you should be aware of before tuning in to the hearing.

Myth #1: “Big Tech companies are monopolies”

There is a difference between the layperson’s use of “monopoly” and the technical meaning of the term. In casual commentary, “monopoly” is often used interchangeably with “large” or “dominant” when describing a company. But the term has a much more precise legal definition, and future court cases will hinge on its technical rather than colloquial meaning. According to DOJ guidelines, a company has monopolized a market when it has “maintained a market share in excess of two-thirds for a significant period and market conditions (for example, barriers to entry) are such that the firm’s market share is unlikely to be eroded in the near future.” The tech companies are not above that threshold:

- Amazon has 38% of the US e-commerce market, including first party sales and sales from third parties on the Amazon Marketplace.

- Apple has 58% of the US smartphone operating system market.

- Google has 29% of the US digital advertising market

- Facebook has 23% of the US digital advertising market.

Amazon is actually a surging competitor in digital advertising, and has an estimated 10% market share this year. It is deeply ironic that multiple Big Tech companies have been accused of monopolizing the advertising market at the same time. In reality, the largest player — Google — has less than a third of the market. The second largest — Facebook — has less than a quarter of the market. And Amazon is nipping at their heels.

Critics of Big Tech often try to define arbitrarily narrow markets to show a market share in excess of two thirds. That’s why you’ll hear that Google has “89-93%” of the US digital search advertising market or a large share of the “US digital display advertising market” or the “US digital video advertising market.” What these critics fail to show is why these should be distinct antitrust product markets. Advertisers maximize return on investment. If prices increase in one advertising channel, they likely substitute that spending to other channels. If anything, the simultaneous rise of digital advertising and fall of print advertising — while other advertising channels have remained flat — suggests that “US digital advertising” might be too narrow of a market. It seems that advertisers are substituting digital advertising for print advertising. A good rule of thumb in antitrust is that the more adjectives someone tries to use to define a market, the less likely it has any relation to economic reality.

It’s also important to remember that in digital markets users often multi-home, meaning they use multiple services in the same market. For example, the average person has nine social media accounts. Take a look at your phone. How many messaging apps do you have? How many social media apps do you have? What about email? Does one company really have a monopoly on how you communicate with your friends, family, and coworkers? Does one company have a monopoly on the entertainment you consume? The answer for most people is no.

Myth #2: “Big Tech harms consumers”

Next, let’s look at consumer harm. According to DOJ guidelines, an antitrust enforcer must show that a company has used its monopoly power to “harm society by making output lower, prices higher, and innovation less than would be the case in a competitive market.” But prices in digital markets have been falling (or at zero) for years.

- The price of digital advertising has fallen more than 40% in the last decade (while the price of print advertising has increased 5% over the same period).

- The price of books has fallen more than 40% since 1997, the year Amazon went public.

- Social media and messaging apps are priced at zero.

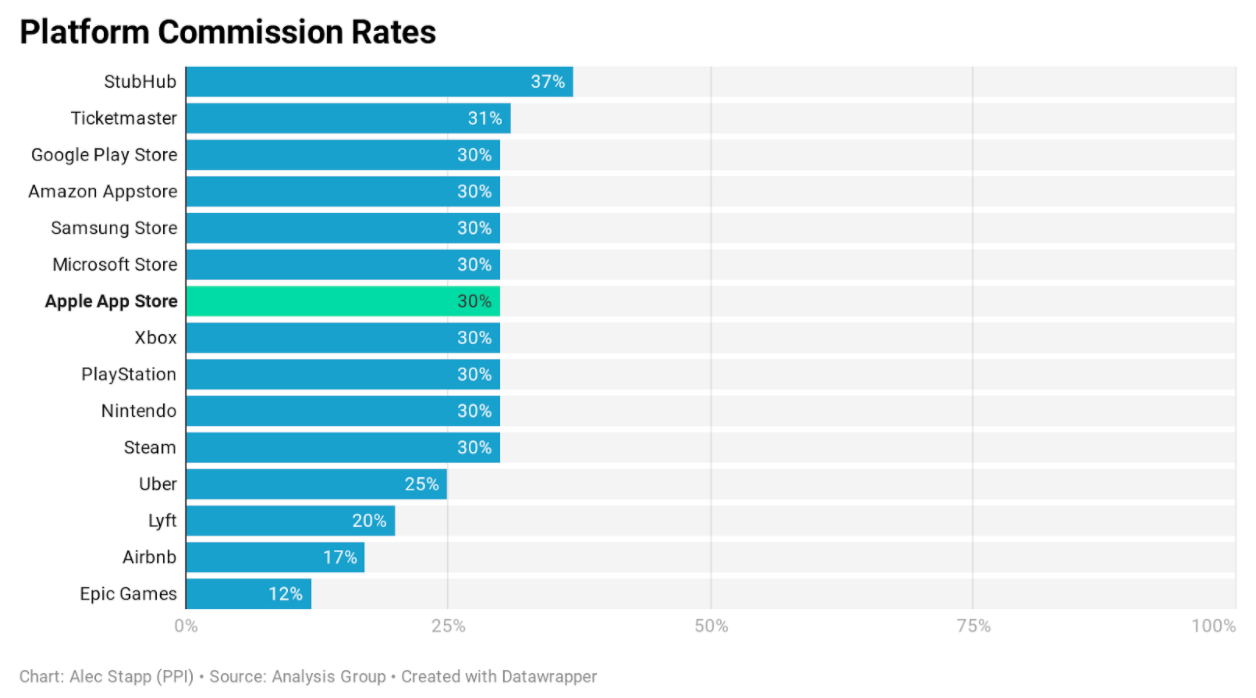

Apple’s 30% App Store “tax” is actually the going rate for platform commissions (and once you account for the revenue generated by free apps, effective app store commission rates are in the range of 4-7%).

While the prices for these services are low or even zero, consumers value them a great deal. Research has shown that, on average, consumers value search engines at $17,530 per year, email at $8,414 per year, digital maps at $3,648 per year, and social media at $322 per year. Again, the price to access these services is typically zero.

Myth #3 “Big Tech doesn’t innovate”

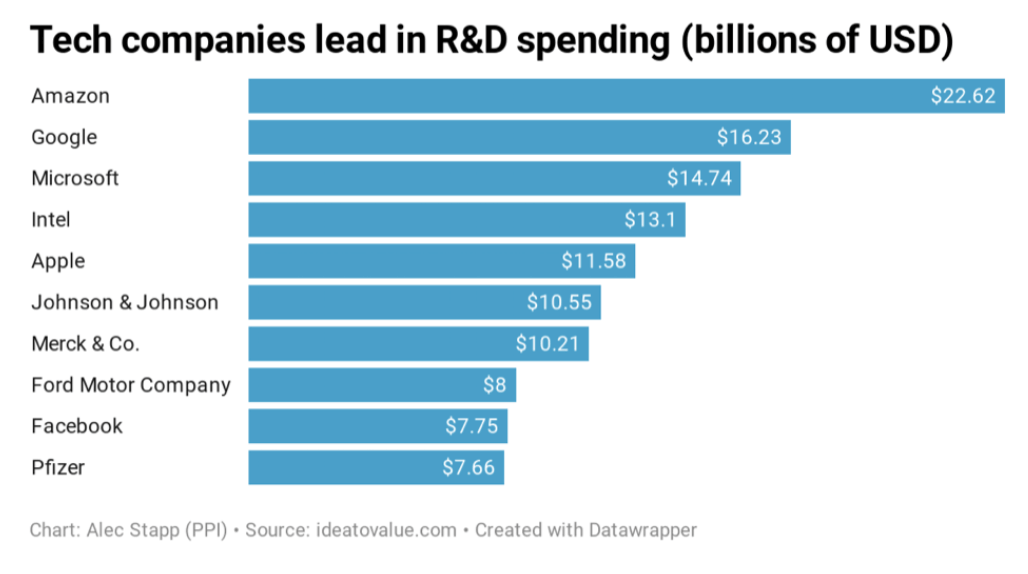

But what about innovation? It’s a hard thing to measure directly. One proxy variable we can look at is spending on research and development (R&D). A complacent incumbent harvesting monopoly rents tends not to invest much in the future. By contrast, in a competitive marketplace, even the dominant firms are nervous they will be unseated by nascent or potential competitors. To prevent that from happening, they invest in the next generation of technology that will benefit consumers.

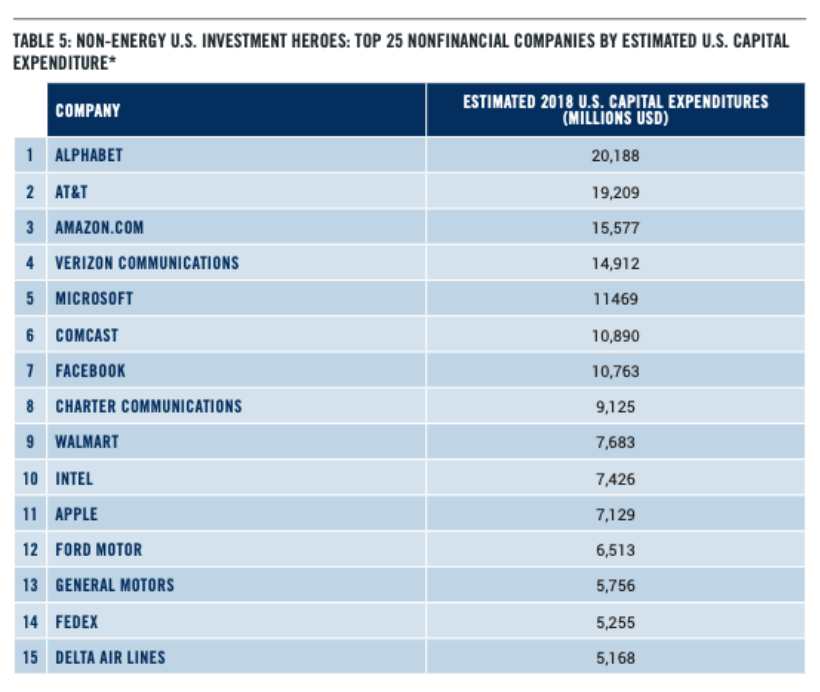

Another metric that’s worth looking at is capital expenditures. The line of reasoning here is similar: a monopolist secure in its market position would rather distribute profits to shareholders than make risky investments. Here again, the tech companies lead the country in spending in this category, according to the Investment Heroes report by Michael Mandel and Elliott Long at PPI.

Myth #4: “Network effects make Big Tech unbeatable”

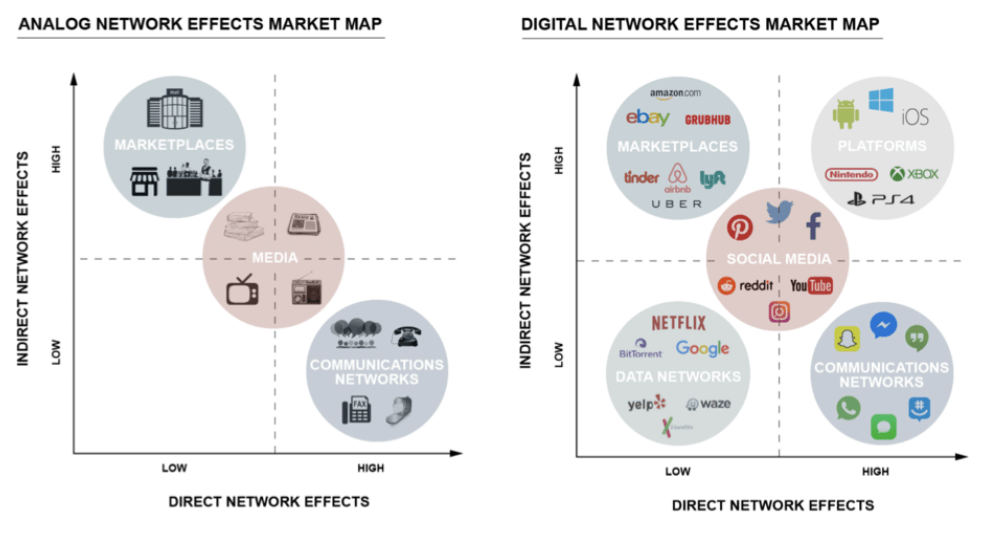

Critics claim that digital markets are different because they have network effects. Network effects are when a service becomes more valuable to each individual user as more users join the network. Telephones are a classic example. A telephone is only valuable insofar as there are other people who also own telephones. A similar dynamic exists for many tech platforms. There are also “indirect” network effects, where one group of customers cares about how many people are in another, distinct group of customers.

For example, operating systems such as iOS and Android need to cater to two different groups — smartphone users and app developers. Smartphone users want to use operating systems that have a lot of apps. App developers want to develop apps for operating systems that have a lot of users. It’s a virtuous cycle. And if there are high switching costs for users or if there are large platform-specific investments that developers need to make, then the equilibrium number of competitors in the market might be only one or two firms.

There are three important facts about network effects to keep in mind. First, network effects are nothing new. As shown in the chart above, many legacy markets have network effects, including fax machines, newspapers, television, shopping malls, and even nightclubs. Second, while network effects can be a source of market power, they can also create large consumer benefits. Breaking up incumbent networks would also destroy these benefits along with dispersing market power, as users lose the positive spillovers from having everyone on the same platform. Lastly, network effects also work in reverse. If a large network begins to lose users, it can quickly unravel as the service becomes less valuable to the remaining users.

Myth #5: “Big Tech is killing the startup ecosystem”

Some Big Tech critics believe the companies create a “kill zone” around their businesses. The hypothesis is that the Big Five are so dominant in their respective markets, no venture capitalists will fund startups to compete with them. Over time, as the tech giants grow and branch out into new markets, we should expect the startup ecosystem to shrivel up and die. This theory is contradicted by numerous prominent examples, including Shopify competing successfully with Amazon and TikTok with Facebook.

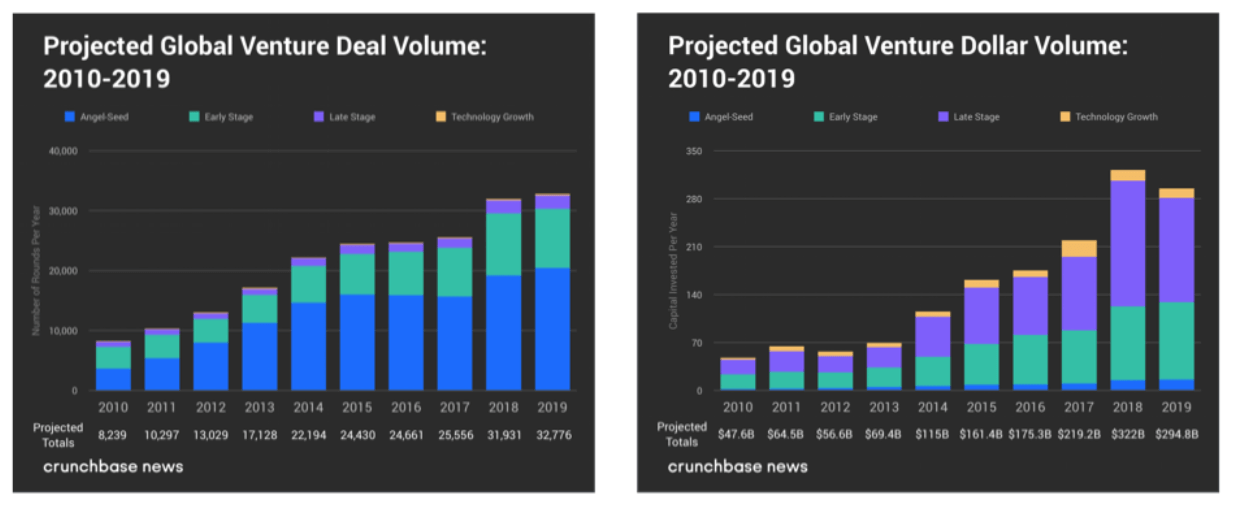

The data on the overall venture capital investment tells a different story. The number of venture capital deals in 2019 reached an all time high of 32,776. The total dollar value of those deals was just slightly off the all time high set in 2018. It seems more likely that startups will die from suffocating on cash than thirsting for liquidity (every Sotbank unicorn investment comes to mind).

And while there is some evidence that venture capitalists are slightly less likely to invest in startups directly competing in a core market for tech giants, this story from Will Rinehart about Google’s founding shows that competition from startups often starts in one narrow market and expands from there:

Google faced a similar environment when it was trying to get off the ground in the late 1990s. Ram Shriram, one of the earliest investors in Google, recently recalled that “I went up and down Sand Hill and could not get a single VC to get a check at the time. The reason? They said search was taken.” Michael Moritz, another early investor in Google, confirmed Shriram’s sentiment and continued by explaining that, “Companies start off with a very narrow focus, and they do one small thing very well, and then they become the best at it, and then they gradually expand.”

As startups get bigger and search for new opportunities for growth, they might increasingly cast their eyes on the cash flows currently enjoyed by Big Tech.

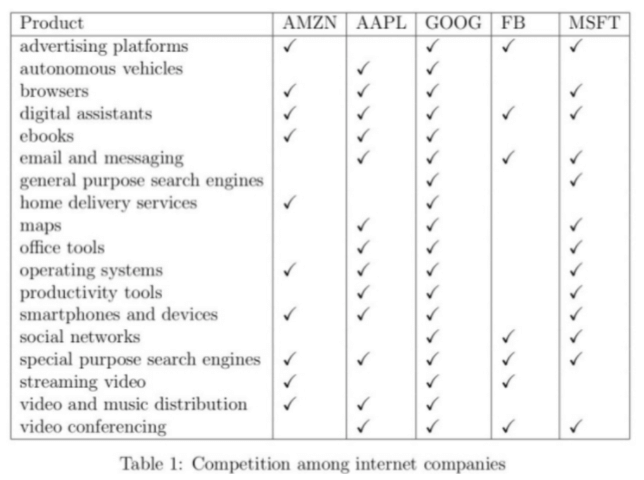

Myth #6: “Big Tech companies only compete in one market”

An underrated source of competition for the tech giants is each other. While each of the Big Five has its core area of strength, they are constantly making incursions on each other’s territory and jockeying for position. As the table shows, for every product or service, there are at least two Big Tech companies offering a competing service (and in many markets it’s four companies). The latest example of this: Google lowered its commission fees to zero on products sold via the ‘Buy on Google’ checkout option and started allowing retailers to use third-party payment and order management services like Shopify. All in the pursuit of challenging Amazon in e-commerce.

Myth #7: “Data is a significant barrier to entry to competing with Big Tech”

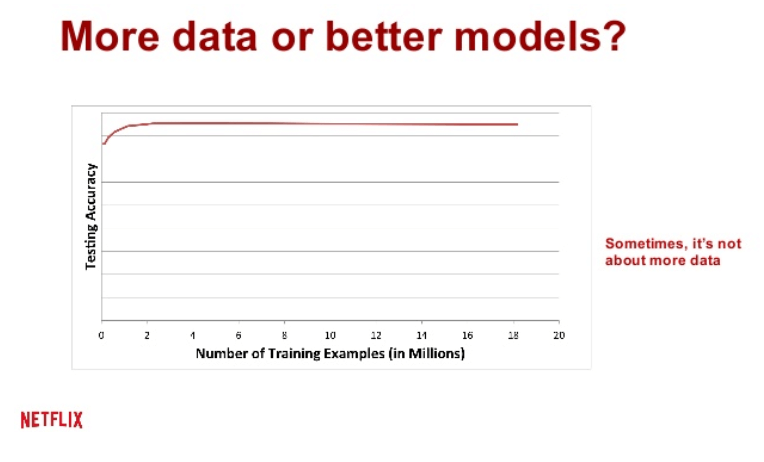

People like to say that “data is a barrier to entry.” But the barrier is much smaller than many think. When data is used as an input for an algorithm, it shows rapidly diminishing returns, as the charts collected in a presentation by Google’s Hal Varian demonstrate. The initial training data is hugely valuable for increasing an algorithm’s accuracy. But as you increase the dataset by a fixed amount each time, the improvements steadily decline (because new data is only helpful insofar as it’s differentiated from the existing dataset).

As the chart above shows, using a real world case of a machine learning algorithm in production at Netflix, adding more than 2 million training examples had very little to no effect. That means the key differentiator is often the quality of the model, not the quantity of data used to train it. And how do you engineer a better model? By hiring top-level machine learning scientists. In the end, the binding constraint is still the humans.

As I’ve written previously, data is not “the new oil.” Data is not like a commodity. It is more akin to a public good — non-rivalrous and non-excludable. For example, if you tell someone your birthday — a discrete piece of personal data — you can’t exclude them from sharing it with other people. And by telling them you have not diminished some finite supply of “birthday tellings.” That piece of information can be shared over and over. And since data is a quasi-public good, that means it is likely underprovided by the market. Private companies can’t capture the full benefits of investing in collecting, processing, and using data. If anything, policymakers should be concerned with how they can promote the safe sharing of more data rather than less (by making it more excludable).

Myth #8: “Stock market concentration is at an all-time high due to Big Tech”

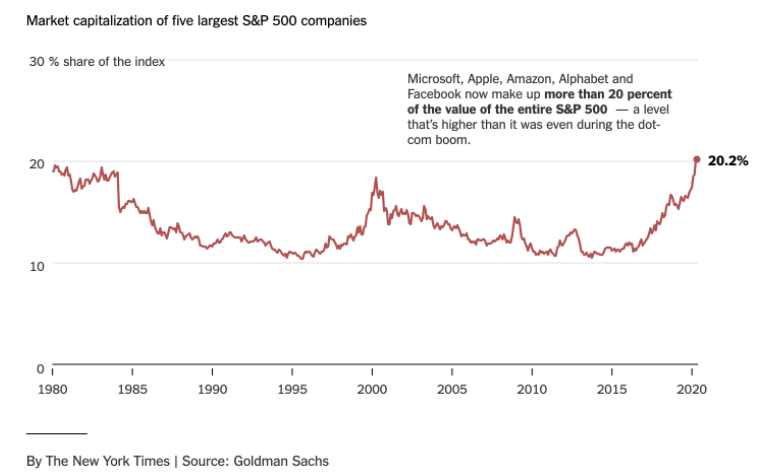

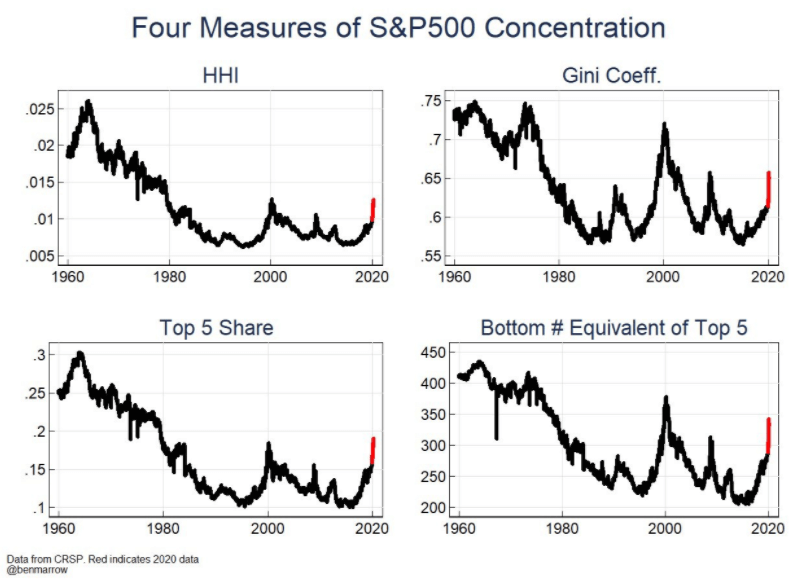

The New York Times and the Financial Times have published articles recently sounding the alarm about the rising concentration in public markets, as measured by the share of the S&P 500 accounted for by the five largest companies in the index (currently Microsoft, Apple, Amazon, Google, and Facebook). The takeaway from these pieces is that concentration is at an all-time high and that it’s unsustainable. But the charts that accompany these articles always seem to start around 1980. What happens if you extend them back further to get more historical context?

As you can see, concentration in the 1960s and 1970s was much higher than it is today. It was normal for the top 5 largest companies to account for more than 20% of the S&P 500, and they even exceeded 30% around 1965. The current level of concentration is not a historical outlier.

Myth #9: “The American public hates Big Tech (‘techlash’)”

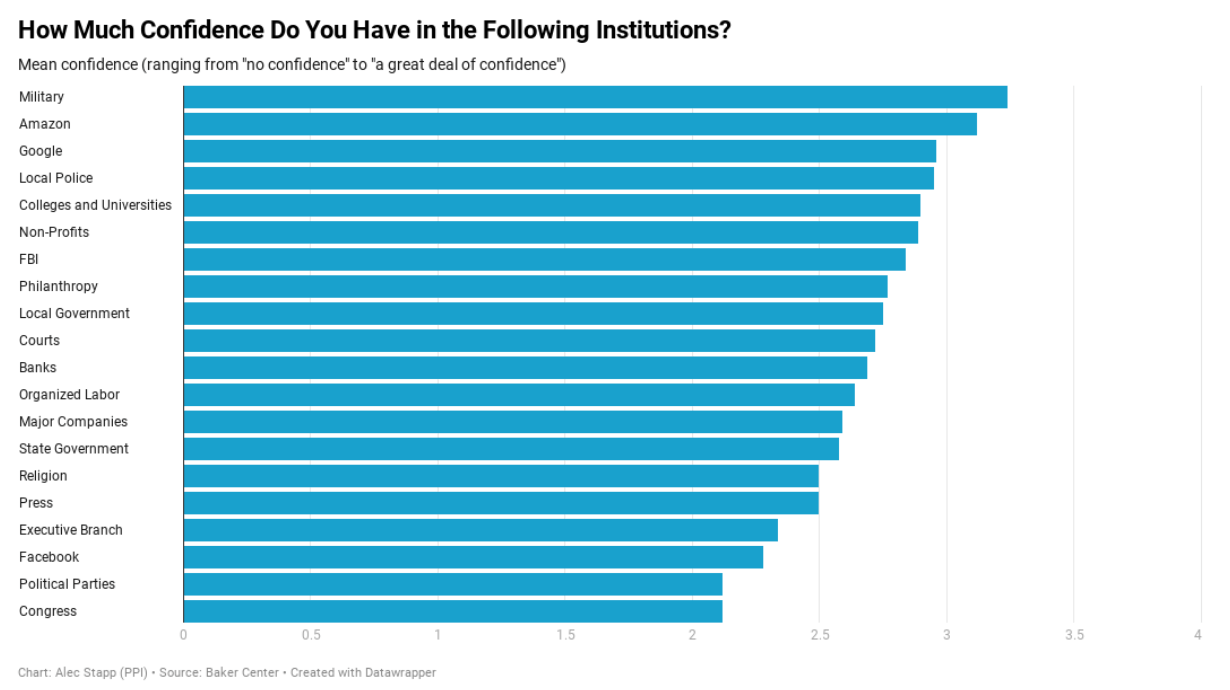

In survey after survey, Americans say they approve of the tech companies, trust them more than companies in other industries, and don’t think politicians should prioritize regulating them more. According to a survey from The Verge, 91% of Americans have a favorable view of Amazon; 90% have a favorable view of Google. According to a poll by the National Research Group, 9 in 10 Americans have a better appreciation for tech during the pandemic. As shown in the chart below, when Georgetown University surveyed Americans on which institutions they had the most confidence in, Amazon and Google ranked second and third respectively, only behind the military. The institution Americans have the least confidence in? Congress.

Myth #10: “It was obvious that some approved Big Tech acquisitions were anticompetitive”

Some critics have claimed that Big Tech engages in “killer acquisitions” and anticompetitive mergers intended to acquire and maintain a monopoly position in the market. This NYT article points out that Google has made 270 acquisitions and Facebook has made 92 acquisitions. The large numbers are supposed to be taken as prima facie evidence of a competition problem. But many of these acquisitions are really just “acqui-hires,” or when one company purchases another for its engineering talent rather than its proprietary technology. As Ben Thompson points out, these exits act as a safety net that encourages entrepreneurs to be more risky in their ventures: “[I[t might have been easier to simply apply for a job at Google or Facebook, but being handed one because you worked for a failed startup reduces the risk of going to work for that startup in the first place.”

Acquisitions are also an essential part of a healthy startup ecosystem. Startups generally have two methods for achieving liquidity for their shareholders: IPOs or acquisitions. According to the latest data from Orrick and Crunchbase, between 2010 and 2018 there were 21,844 acquisitions of tech startups for a total deal value of $1.193 trillion. By comparison, according to data compiled by Jay R. Ritter, a professor at the University of Florida, there were 331 tech IPOs for a total market capitalization of $649.6 billion over the same period. Those liquidity events reward investors and employees for taking risks and incentivize the next round of startup financing.

But the main problem with labeling past acquisitions “anticompetitive” — even if they were reviewed by antitrust authorities and explicitly approved at the time — is hindsight bias. Because Instagram now has more than a billion users and is arguably a more valuable asset to Facebook than its legacy social network, critics are implicitly claiming that Instagram would have experienced the same success as an independent company. In other words, its success was a foregone conclusion.

Nothing could further from the truth. A cursory review of the historical record makes it clear how much doubt there was at the time about the wisdom of acquiring a photo-filtering app for $1 billion. Instagram had just 30 million users and zero revenue. The company had raised money at a $500 million valuation the day before Zuckerberg made the $1 billion offer. On late night TV, Jon Stewart joked about the acquisition: “A billion dollars of money? For a thing that kind of ruins your pictures? The only Instagram worth a billion dollars would be an app that instantly gets you a gram.”

A CNET article by Molly Wood titled “Facebook buys Instagram…but for what?” had this conclusion:

I still feel like there are more questions than answers to why this price tag makes sense. I hope Facebook isn’t getting distracted by hipster buzz or the photo-sharing bubble, especially at a time when its business decisions need to be as sound as possible to shore up future investor confidence. Don’t spend those billions before you’ve got them, guys.

The same is true for other Big Tech acquisitions. When it comes to a prospective merger, the tech companies are damned if they do, damned if they don’t. If it fails, people call it a “killer acquisition.” If it succeeds, people say the company took out a future competitor.

Conclusion

One of the biggest misnomers in the antitrust discourse is that people presume all monopolies are illegal. According to the FTC,

[I]t is not illegal for a company to have a monopoly, to charge “high prices,” or to try to achieve a monopoly position by what might be viewed by some as particularly aggressive methods. The law is violated only if the company tries to maintain or acquire a monopoly through unreasonable methods. For the courts, a key factor in determining what is unreasonable is whether the practice has a legitimate business justification.

Of course, based on the evidence presented earlier, it is far from clear that the tech companies have even a legal monopoly in any antitrust product market, let alone an illegal monopoly acquired via exclusionary conduct. But it is self-evidently true that the Big Five have been wildly successful and have become dominant in their respective core areas. Upon reviewing the totality of the evidence, the more likely explanation for their size is that they’ve created some of the best products in the market and are more efficient at delivering what consumers want than their competitors.

Given the facts of the market, why would Congress choose to hold a hearing about Big Tech and antitrust at a time like this? Antitrust regulators have been serving as effective watchdogs of actual anti-competitive conduct and should continue to do so in the future. There may be room for behavioral remedies in tech that strike a better balance without blowing up our most valuable and innovative companies. But, of course, that requires more focus on the boring procedural work of careful antitrust analysis — and that doesn’t make good TV.

SEC in Focus: Lack of Diversity Among Asset Managers

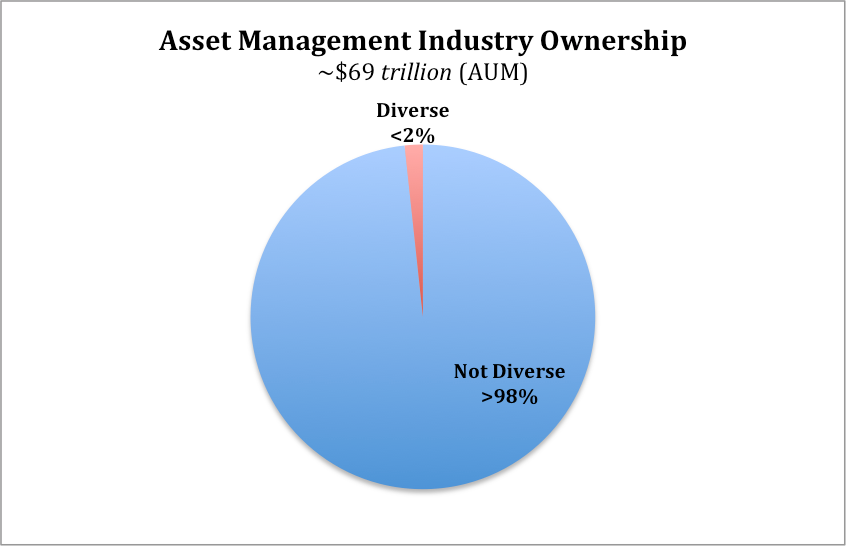

In July 16 the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) hosted a discussion on improving diversity and inclusion within the asset management industry.

The SEC doesn’t have a long history of using its powers to focus on diversity, but SEC Chairman Jay Clayton sounded an optimistic note: “We should continue to ask ourselves how we want participation and representation in our markets to evolve, at all levels,” Mr. Clayton said at the meeting.

But government can’t do it alone. To wit- just 69 of 1,367 entities surveyed by the SEC in 2018 completed an assessment of their diversity policies and practices, according to the agency.

Some diversity advocates implored the SEC to increase pressure by declining to meet with firms that ignore its diversity surveys.

While the increase of these discussions by the government is welcome, withholding access to your government is never a good idea.

One chart explains the reason the SEC hosted this discussion

Why is this chart so important? It speaks to opportunity — which is the essential precondition of equality. Simply put, how can we expect investment capital to flow to minority and women entrepreneurs if it’s not flowing through the hands of diverse capital allocators?

Congressional Red Alert: Local governments need help — ASAP

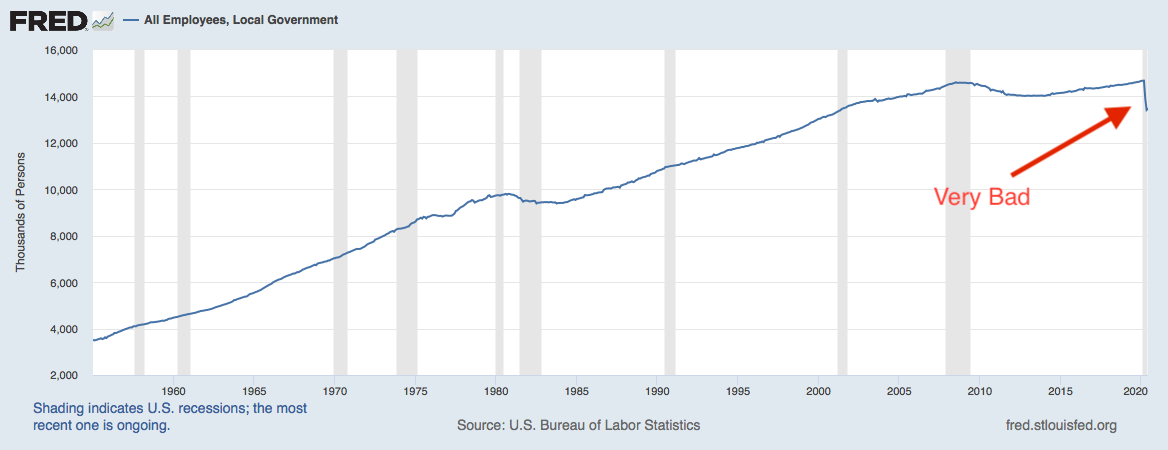

Still not convinced this recession is different? Take a look at this graph from the Federal Reserve of St. Louis:

This chilling drop-off is one of several reasons to get emergency funding directly to states and cities in the next stimulus package. The chart dates back to 1955 and shows that local governments who are hemorrhaging money are shedding jobs at a record pace. (Previous recessions are shaded)

In March 2020, local governments employed nearly 14.7 million people. Two months later that number dropped to 13.4 million with more cuts expected soon. Those job losses moved across various sectors including fire, police, teachers, and frontline healthcare workers.

How Amazon advances clean energy goals, while nurturing innovation and shareholder capital

Amazon announced it has teamed up with We Mean Business, a global non-profit working with business to accelerate the clean energy transition.

This push by Amazon is reflective of a larger trend by cash rich companies and is an important focus by businesses that have significant resources to allocate. If you dig closer, you will find more and more of these proposals have a capital investment component in clean energy technology. From the press release:

Climate Pledge signatories will explore investment opportunities, including through Amazon’s Climate Pledge Fund, in companies whose products and services will facilitate the transition to a zero-carbon economy.

New York uses green infrastructure investment to get its economy back on track

Amid a massive economic crisis on the heels of serving as America’s first Covid-19 epicenter, New York’s Governor Andrew Cuomo has forged ahead with plans for an historic solicitation of renewable energy via offshore wind farms. Combined with a $400 million multi-port public/private infrastructure investment, these actions are key components to get New York State’s economy back on track and progressing towards its mandate to secure 70% of its electricity from renewable sources by 2030.

“During one of the most challenging years New York has ever faced, we remain laser-focused on implementing our nation-leading climate plan and growing our clean energy economy, not only to bring significant economic benefits and jobs to the state, but to quickly attack climate change at its source by reducing our emissions.” Gov. Cuomo said.

Glaring omission in the CARES Act commission highlighted

Thornell, et al, make a pretty convincing case in Barron’s that the oversight commission for the CARES Act as currently constructed, is problematic to help get money needed to the 8.7 million employees of minority-owned businesses, hardest hit since the crisis began and overlooked in previous stimulus packages. Why? There are no minorities on the current commission. The solution according to the authors? Add more members to the commission, and this time- include minorities.

From the piece: “No requests were made of the Treasury Department and Federal Reserve Board to explore the array of economic implications for communities of color or inquire about possible strategies to address them. The Treasury and the Fed wield powerful economic tools to manage the pandemic’s devastation on businesses, workers’ livelihoods, family savings, and consumer confidence.”

Agreed. I highlighted similar inclusive governance challenges in an op-ed for The Hill in April arguing why Biden needs some diversity in key economic cabinet posts that have never been led by a minority.

Meanwhile… “Inside the Klubhouse”

The Institute for Diversity and Ethics In Sport (TIDES) at the University of Central Florida last week released its 2020 Racial and Gender Report Card for the NBA. Commissioner Adam Silver, owners, and players have been longtime leaders on social issues among all mainstream sports, so these results are no surprise:

Case in point from the San Antonio Spurs last week. Coach Gregg Popovich, a 5x Champion, top 3 all time, future hall of fame coach, swapped roles with assistant coach Becky Hammon, who took over head coaching duties for the Spurs against the Milwaukee Bucks.

Should we abolish tax returns? A conversation with Sen. Bob Kerrey

Former Senator Bob Kerrey joins the Center for New Liberalism and the Progressive Policy Institute’s Paul Weinstein and Alec Stapp to discuss whether or not the US government should adopt return-free filing for individual taxes.

The participants will discuss the costs and benefits of return-free filing relative to our current voluntary tax filing system, the main problems with our current tax system, and whether or not return-free filing would reduce tax evasion.

Investment Heroes 2020

This post has been updated to include additional data, as well as updating our original preliminary estimate of Microsoft’s capital expenditures to reflect their since-released 10-K report.

Given the ongoing pandemic, capital investment is more important than ever before. Hundreds of billions of dollars of investment by broadband providers enabled the U.S. Internet to respond magnificently to soaring demand when the pandemic hit. On the other hand, some of the sectors that have struggled the most—such as medical equipment and supplies and food production and processing—have suffered from a shortfall of investment.

To emphasize the importance of capital spending for wages and growth, each year the Progressive Policy Institute publishes our list of U.S. “Investment Heroes:” the companies who are investing the most in America. Currently, accounting rules do not require companies to report their U.S. capital spending separately. To fill this gap in the data, we created a methodology using publicly-available financial statements from non-financial Fortune 150 companies to identify the top companies that were investing in the United States.

Table 1 below provides the top 25 non-financial companies, ranked by U.S. capital expenditure in the latest fiscal year through June 30, 2020. Table 2 below provides the top 25 nonfinancial non-energy companies, ranked by U.S. capital expenditure in the latest fiscal year through June 30, 2020 (Our methodology is described in last year’s report. In particular, page 15 of that report describes adjustments made for particular companies).

We note that 10 out of the top 11 companies in Table 2 are either broadband providers or tech/ecommerce companies. Out of those ten, the broadband providers invested $52 billion in the United States in their most recent fiscal year, while the tech/ecommerce companies invested $84 billion.

| Table 1. U.S. Investment Heroes: Top 25 Nonfinancial Companies by Estimated U.S. Capital Expenditure | ||||

| Rank | Company | ESTIMATED 2019 U.S. CAPITAL EXPENDITURES (Millions USD)* | ||

| 1 | Amazon.com | $19,306 | ||

| 2 | AT&T | $18,520 | ||

| 3 | Alphabet | $18,037 | ||

| 4 | Exxon Mobil | $16,580 | ||

| 5 | Verizon Communications | $16,058 | ||

| 6 | Intel | $13,416 | ||

| 7 | $12,457 | |||

| 8 | Duke Energy | $11,122 | ||

| 9 | Microsoft | $11,073** | ||

| 10 | Comcast | $10,467 | ||

| 11 | Chevron | $10,062 | ||

| 12 | Apple | $9,772 | ||

| 13 | Walmart | $7,904 | ||

| 14 | Southern | $7,880 | ||

| 15 | Exelon | $7,248 | ||

| 16 | Charter Communications | $7,195 | ||

| 17 | Ford Motor | $6,414 | ||

| 18 | Energy Transfer | $5,960 | ||

| 19 | Marathon Petroleum | $5,374 | ||

| 20 | Delta Air Lines | $4,936 | ||

| 21 | ConocoPhillips | $4,907 | ||

| 22 | General Motors | $4,899 | ||

| 23 | United Parcel Service | $4,793 | ||

| 24 | FedEx | $4,647 | ||

| 25 | Enterprise Products Partners | $4,532 | ||

| Top 25 Total | $243,560 | |||

Data: Company financial reports, PPI estimates |

||||

| Table 2. Non-energy U.S. Investment Heroes: Top 25 Nonfinancial Companies by Estimated U.S. Capital Expenditure | ||||

| Rank | COMPANY | ESTIMATED 2019 U.S. CAPITAL EXPENDITURES (Millions USD)* | ||

| 1 | Amazon.com | $19,306 | ||

| 2 | AT&T | $18,520 | ||

| 3 | Alphabet | $18,037 | ||

| 4 | Verizon Communications | $16,058 | ||

| 5 | Intel | $13,416 | ||

| 6 | $12,457 | |||

| 7 | Microsoft | $11,073** | ||

| 8 | Comcast | $10,467 | ||

| 9 | Apple | $9,772 | ||

| 10 | Walmart | $7,904 | ||

| 11 | Charter Communications | $7,195 | ||

| 12 | Ford Motor | $6,414 | ||

| 13 | Delta Air Lines | $4,936 | ||

| 14 | General Motors | $4,899 | ||

| 15 | United Parcel Service | $4,793 | ||

| 16 | FedEx | $4,647 | ||

| 17 | United Continental Holdings | $4,528 | ||

| 18 | American Airlines Group | $4,268 | ||

| 19 | Walt Disney | $4,024 | ||

| 20 | CenturyLink | $3,628 | ||

| 21 | HCA Healthcare | $3,537 | ||

| 22 | Union Pacific | $3,453 | ||

| 23 | Kroger | $3,128 | ||

| 24 | Target | $3,027 | ||

| 25 | CVS Health | $2,457 | ||

| Top 25 Total | $201,945** | |||

Data: Company financial reports, PPI estimates |

||||

(Analysis by Elliott Long and Michael Mandel).

Credit Rating Agencies: Sending A Clear Signal

INTRODUCTION

The Covid-19 pandemic has sent the global economy and financial markets into an unprecedented crisis. The path of the downturn and recovery is difficult to discern. Some companies and nations are likely to survive and prosper, while others will struggle indefinitely.

In this context, bond markets will be looking to rating agencies to objectively assess the changing prospects of bond issuers, both private and public. Even the Federal Reserve is counting on the rating agencies—the Fed’s own rules for which bonds it can purchase under the new Primary Market Corporate Credit Facility explicitly reference the ratings produced by major nationally recognized statistical rating organizations (“NRSRO”).1

Can the credit rating agencies be trusted to do a good job analyzing the credit prospects of borrowers in the downturn? Will the resulting rating actions balance the needs of investors, issuers, and the financial markets? Will ratings downgrades unnecessarily make the economic and financial situation worse?

Before the virus struck, two independent advisory committees at the SEC in the United States were in the process of examining the business and compensation models of credit rating agencies such as Moody’s Investors Service and S&P Global. The issue was whether their “issuer pays” business model gives them an incentive to inflate the initial ratings of corporate bonds and other securities, or an incentive to slow-walk necessary ratings downgrades in tough times. Several meetings were held at the SEC in 2019 and 2020 to discuss alternative compensation models that might not have the same conflicts of interest.

But despite these criticisms, the strengths of the current model of fixed income credit ratings— built around transparency and reputation—are often overlooked.

The market for ratings for fixed income securities has developed a set of incentives and institutions that consistently produce strong signals that are useful for market participants, even in uncertain times.

This paper examines the pluses and minuses of the “issuer pays” model of credit ratings. The current model helps solve two information problems simultaneously. First, it’s hard for financial intermediaries such as mutual funds and life insurance companies to assess all the different bonds that they might invest in. Second, it’s difficult for individuals who trust their money to these financial intermediaries to monitor the soundness of their portfolios. Well-understood ratings by an independent rater address both problems.

We compare the issuer-pays to alternative models, such as “investor pays” and government-sponsored ratings. We conclude that despite potential conflict of interest problems, the “issuer pays” produces a stronger and less biased signal for market participants. We look back at the 2008-2009 financial crisis and see that ratings were inversely correlated with 10-year default frequencies even in the disrupted residential mortgage-backed securities (RMB) and collateralized debt obligation (CDO) markets, just as they should be.

We also address the knotty question of “procyclicality”—whether the rating agencies are too lenient in good times and then compensate by being too tough when the credit market turns down. We look at the recent evidence and suggest that there’s no reason to believe that the alternative business models do a better job than the “issuer pays” model in generating useful information in downturns.

We then set the business model and practices of the credit rating agencies in a broader context. In every part of the economy, the Information Age has made an exponentially increasing amount of data available to everyone. The difficult problem is extracting useful signals from the noise, especially when some market participants are actively taking advantage of opportunities to manipulate data, or to create false signals.

The credit ratings market, based on the issuer pays model, seems to have a way to consistently produce high quality and more accurate ratings that give strong and useful signals to market participants. Another benefit of independent credit rating agencies is that they set a global language – a global standard of comparison. This is especially important at times of stress, like now, when credit facilities need to be set up quickly.

Finally, we ask the important policy question of whether the “issuer pays” model provides any useful lessons for other areas of the economy struggling with extracting signal from noise, such as journalism and safety certification of new products.

BACKGROUND

Why do credit rating agencies exist? Whose interests do they serve? Bond issuers, from small companies to giants, sell a wide variety of fixed income securities. These are mostly bought by financial institutions such as banks, mutual funds, and insurance companies, who are functioning as financial intermediaries. For example, the 2019 financial accounts report from the Federal Reserve shows that out of the $14 trillion in corporate bonds, only $937 billion are held directly by U.S. households and nonprofits.2 That’s less than 7 percent. Households invest in corporate bonds indirectly, through financial intermediaries. They own shares in bond mutual funds, which in turn own corporate bonds. Or they have paid for life insurance, and the life insurance companies invest in turn in corporate bonds.

Here is a schematic diagram that shows the flow of money supporting the fixed income markets. The role of the credit rating agencies is to help solve not one but two information problems. First, financial intermediaries like mutual funds and life insurance companies want to have some way of assessing the riskiness of the bonds they are buying from the issuers.

Obviously they do their own analysis. But it’s also helpful to have an independent source of ratings, since the issuer has an incentive to minimize potential risks.

In theory, financial intermediaries could do without the ratings agencies, if they are willing to put enough money into analyzing every bond. However, fully shifting the bond riskiness assessment to the financial intermediaries wouldn’t solve and might even worsen the second information problem: The financial intermediaries buying the bonds have an incentive to understate the riskiness of their portfolio for households, other investors and regulators. Moreover, households and regulators generally do not have the resources to independently assess the riskiness of the portfolios of the financial intermediaries. Most households and retail investors, of course, are not direct users of credit ratings. But indirectly ratings provide guardrails for financial intermediaries such as life insurance companies, guiding which bonds they can invest in and reassuring buyers of life insurance policies that their money will be safe.

In effect, the ratings do double duty. They are used by the bond buyers to assess the riskiness of the bonds. In addition, they are used by households and regulators to assess the riskiness of the portfolios of the financial intermediaries as well. Any alternative to the current business model has to take into account both uses. (Figure 2).

HOW THE RATING PROCESS WORKS

Under the current model, the issuer of a bond pays the rating agency or agencies for the initial rating of a security, as well as ongoing ratings. Different rating agencies use different lettering schemes, but there is widespread agreement about what counts as investment grade bonds and what counts as speculative grade.

More precisely, the rating is an assessment that the bond can withstand a particular level of economic stress. For example, S&P lays out a chart that says that a AAA-rated bond can withstand a downturn on the level of the 1929 Great Depression.3

Unfortunately, no one, including the credit rating agencies, can forecast how deep the pandemic-related economic downturn can go.

As it heads into 1929 territory, it’s possible that some top-rated corporate bonds may default. Even under less stressful circumstances, the rating agencies cannot predict how the global economy or financial markets will perform.

Moreover, we can reasonably expect sectorspecific shocks that affect bonds in one sector differentially. For example, the current coronavirus crisis has the potential to cause significant downgrades of bonds issued by travel companies such as airlines and hotels. Meanwhile residential mortgage-backed bonds got hit hard during the 2008-09 financial crisis.

Given the unpredictability of the financial markets and the economy, the rating agencies can reasonably be expected to assess relative riskiness within a sector.

Table 2 is based on the performance summaries that the credit rating agencies are required to supply to the SEC annually. We looked at the tenyear period starting with 2006, the year before the financial crisis started, and focused on the performance of ratings issued for the RMB and CDO markets. These are two of the sectors that were disrupted the most in the 2008-09 financial crisis. We combined the data for Moody’s and S&P Global.4,5

We see that for these two important sectors, the rating on a security in 2006 is inversely correlated with the frequency of defaults 10 years later. The higher the initial rating, the lower the frequency of defaults.

THE FINANCIAL CRISIS OF 2008-09

Under the current model, the issuer of a bond pays the rating agency or agencies for the initial rating of a security, as well as ongoing ratings. Different rating agencies use different lettering schemes, but there is widespread agreement about what counts as investment grade bonds and what counts as speculative grade.6

In response, the Dodd-Frank Act of 2010 called for the SEC to study alternatives to the “issuer pays” business model, as well as other regulatory reforms. In addition, the Department of Justice, in combination with some state attorneys general, launched lawsuits accusing S&P and Moody’s, in particular, of defrauding investors.

The lawsuit against S&P was settled in 2015, focusing on a small number of incidents where internal procedures weren’t followed.7 A similar lawsuit against Moody’s was settled in 2017, with the rating agency agreeing to do a better job following its published rating procedures.8 In neither case was there sufficient evidence for a finding of fraud.

POTENTIAL BIAS

The obvious bias in the issuer pays model is that the ratings agencies compete to offer issuers better ratings. To put it another way, an issuer can engage in “ratings shopping” by choosing to pay the agency that offers the higher rating.

But study after study has shown much less evidence of rating shopping than one might expect. Most bond buyers only want to invest in securities that are rated by multiple agencies. That means rating agencies are under less pressure to boost ratings.

It is true that among single-rated securities or tranches, there is evidence that bond issuers are choosing the agency that offers the higher rating, as one might expect. One study found that for mortgage backed securities, “outside of AAA, realized losses were much higher on single-rated tranches than on those with multiple ratings, and yields predict future losses for single-rated tranches but not for multi-rated ones.”9

However, it turns out that bond buyers are not stupid. When they see a single-rated security, they are less likely to trust the rating than if it has been rated by multiple rating agencies. One 2019 study found that “bonds with upwardbiased ratings are more likely to be downgraded and default, but investors account for this bias and demand higher yields when buying these bonds.”10

In other words, the combination of the rating and the number of raters—both publicly observable pieces of data—produces useful information for participants in the bond market. In other words, the bias is partly self-correcting.

MITIGATING THE BIAS

Still, it is clear that credit rating agencies face conflicts of interests, much like other participants in financial markets. Accounting auditors face pressure to give good grades to their clients. Investment banks face pressure to overstate the potential of the initial public offerings that they help bring to market. And even regulators face conflicts of interest, since a typical career path often leads out of government to the regulated industry.

Like these other institutions, internal controls at the rating agencies can help mitigate the bias towards higher ratings. That includes internal separation of sales and analysis, so that the people assigning a rating to a bond are not in direct contact with the issuer of the bond. In addition to internal controls, credit rating agencies are heavily regulated around the world. That includes annual exams in the U.S. by a regulator who has significant authority to take action if any violations occur—including revoking a credit rating agency’s license to operate.

Even with these internal controls, though, the real mitigating institutions are transparency and reputation.

Transparency

The agencies assess the creditworthiness of the bonds according to published and detailed methodologies.11 In fact, there is literally nowhere else in the private sector that gives this level of transparency into the intellectual property of an organization, or that so rigorously documents their internal methodology for making decisions (imagine a newspaper committing itself publicly for how it chooses stories or does reporting, including reporting on advertisers). From the perspective of users of the ratings, the public nature of the ratings methodologies is essential. On transparency, one of the key benefits of an issuer-pays system is the fact that allows ratings to be released publicly – meaning they’re scrutinized every day by all corners of the market, the media, and academia. The ratings agencies cannot be judged on the performance of the ratings they issue, because of the uncertain effects of future events. But they can be judged on whether they follow their published methodologies.

Reputation

The other institution that mitigates bias is the need to preserve reputation. Credit rating agencies know that credit booms always end in a recession or credit crisis. The exact nature of the crisis can’t be predicted—the concept of a global pandemic, even if acknowledged within the realm of possibility, was part of very few reasonable scenarios. But when the crisis comes, credit rating agencies can be sure that their rating decisions will be challenged ex poste.

Their initial rating decisions will be criticized for being excessively sanguine. Their ratings downgrades will be attacked for either being too slow (leading to investors being misled) or too rapid (potentially undermining the economic viability of a bond issuer). All of their internal decision-making processes will be scrutinized and investigated.

This sort of intense scrutiny is only reasonable. Rating agencies do all of their work out in the open. They issue public ratings, and the performance of the ratings is visible as well. It’s not possible to investigate all of the bond issuers, so the ratings agencies are a proxy. They are an easy target, and that’s a good thing.

One can think of this as a long-term equilibrium where the rating agencies make good profits during the boom periods assigning ratings.

During the downturn it’s revealed how well their ratings performed. In addition, after the inevitable investigations, the rating agencies can expect that their internal rating process will be revealed as well. They therefore have a strong incentive not to cut corners and preserve their reputation so that they can survive the investigations of the downturns.

Indeed, issuers will not use the ratings if investors don’t trust in their independence and the strength of the models. In fact, demand for the use of certain credit rating agencies comes from the performance of their ratings over time and the ongoing judgment of investors.

ALTERNATIVE COMPENSATION MODELS

Is there a better way? Dodd-Frank charged the SEC with examining alternative business models for ratings agencies, since issuer pays has an obvious conflict of interest. Meeting in late 2019 and early 2020, the SEC’s Fixed Income Market Structure Advisory Committee looked at the question, in the words of SEC Chairman Jay Clayton: “Are there alternative payment models that would better align the interests of rating agencies with investors?”12

Economists, regulators, and financial market participants have suggested a variety of alternative compensation models designed to reduce conflicts of interest while still maintaining the critical function of the ratings agencies. A 2012 report from the GAO identified seven possibilities, though several had never been tried in the real world. At the end of the day, the only plausible alternatives are some form of “investor pays” and random assignment.

Investor Pays

One option is to require the investor to pay for ratings, like a subscriber fee. More precisely, it’s better to say that “financial intermediaries pay” since financial intermediaries such as mutual funds, pensions, and life insurance companies own the majority of fixed income securities.

The shift to “financial intermediaries pay” removes one conflict of interest, at the cost of creating two more. On the one hand, at the time of issue, it’s better for the bond buyer if the rating is cautious, so that the bond will be priced lower and pays a higher yield. On the other hand, financial intermediaries prefer that the rating agencies are slow to downgrade, to make their portfolios look better to final investors and regulators.

It’s also true that there are fewer financial intermediaries than bond issuers. Moreover, financial intermediaries tend to have the resources to do their own analysis if needed. They are therefore less dependent on the rating agencies, and have less need for the information.

In the end, there is no compelling case that the “investor pays” model is superior to the “issuer pays” model. Moreover, it’s hard to see how an “investor pays” model would work without strict government rules.

Random assignment

The critics who worry about issuers shopping for ratings keep coming back to the same solution: Random assignment of rating agencies to new bond offerings. When an issuer wanted to have a bond rated, they would apply to a central organization that would randomly assign a credit rating agency off of a list of approved agencies. The agency would then get paid for its work at a fixed rate.

In effect, the “random assignment” compensation model turns credit ratings into a government-run utility using “fixed price” contractors. As with all government-run utilities, there would be pluses and minuses.

On the one hand, random assignment reduces or eliminates the ability of issuers to shop for better ratings, which is the intention. That means rating agencies would not have an incentive to artificially boost ratings.

But as in the case of “investor pays,” eliminating one problem creates two new problems. First, under the random assignment compensation model, rating agencies have no incentive to put effort into producing high quality ratings, since they get picked randomly even if they do just an average job. Credit rating agencies would be investing the money in innovation. As a result, the random assignment approach may produce ratings that are less biased but also less accurate. Moreover, there might be an incentive to set ratings artificially low to avoid downgrades.

The second and related problem is deciding which rating agencies are on the approved rotation list—which ones are eligible, and which ones need to be removed for bad performance. That requires a government “gatekeeper” to assess the short-term and long-term performance of each agency and which ones are “good enough” to be on the list.

There are two approaches to assessing performance of rating agencies. One is to look at measurable outcomes—for example, the frequency of defaults and large downgrades. These must be measured over an entire credit cycle, so it’s tough to see how they can be applied in the short run. Moreover, any “objective” measure will be gamed by new rating agencies that want to get on the list.

The other approach is to set up a standard that is based on minimum capabilities. That is, the government gatekeeper would add to the list any rating agency that has enough licensed analysts and published methodologies. The result is that more competition is likely to lead to worse quality ratings.

There’s one final important point. One of the biggest and most politically fraught rating decisions is how to assess sovereign debt, and in particular the debt offerings of the U.S. government. With the government as the gatekeeper for the random assignment list, there’s likely to be pressure on rating agencies not to downgrade government debt even if appropriate. The conclusion is that the shift to a random assignment system is likely to produce new unknown biases in ratings.

PROCYCLICALITY

One charge levelled against the current “issuer pays” model is that it leads to “procyclicality.” If ratings were procyclical, that would mean that the rating agencies go too easy on issuers in good times, and then are forced to be tough and downgrade bonds in bad times. In this way, say the critics, ratings procyclicality can end up making the booms bigger and the downturns worse.

However, the evidence for ratings procyclicality is, to put it mildly, mixed. A July 2020 report from the SEC observed that “ratings downgrades are generally lagging indicators of cost of debt capital. Moreover, consider the issue of whether rating agencies have been giving “too high” ratings to corporate borrowers in recent years. In a February 2020 report, the OECD directly addressed that question, comparing the pattern of ratings by one credit rating agency in 2017 with 2007. The report found that at the same rating level, borrowers in 2017 had a higher level of debt relative to various measures of cash flow and earnings.

By itself, that result suggests that credit rate standards had gotten easier in 2017 compared to 2007. However, the report then admits that low interest rates made it easier for corporate borrowers to cover their debt payments in 2017 compared to 2007, providing evidence that credit standards had not gotten easier.

In truth, the procyclicality argument is a bit of a red herring. When the credit cycle turns down, credit rating agencies are stuck no matter what they do. If they are conservative and cautious about downgrading bonds, they are accused of protecting their issuers. If they downgrade aggressively, they are accused of making the recession worse. The cries are especially loud when sovereign debt issued by governments is downgraded, since such a move has a broad effect on the ability of governments to raise money.

Moreover, there’s no evidence that the alternative compensation models would do any better. Under the “investor pays” model, the rating agencies will come under strong pressure from investors to not downgrade the bonds in their portfolios in downturns, making ratings untrustworthy at precisely the moment they are needed the most. And as we point out in the previous section, under the “random assignment” model, any rating agency that downgraded the government might find itself out of the rotation in the future.

OTHER APPLICATIONS OF ISSUER PAYS

For all their flaws, independent credit ratings agencies, paid by issuers, produce a strong and useful signal in a noisy information environment. It isn’t perfect, but the ratings perform well, and users are able to adjust for potential conflicts of interest. The combination of transparency and reputation seem to create sufficient incentives to make it worthwhile for the credit rating agencies to take their job seriously and produce information that issuers, financial intermediaries, and households and regulators can’t do without.

In the broader sense, one gets a sense that the current “issuer pays” credit rating system is actually a pretty decent way of solving a difficult problem that occurs across the economy—certifying the quality of products and services. An independent third party is paid by the producer or manufacturer of the product or service to do the certification (“issuer pays”). One key is that the payment has to be large enough that the certifying organization has an incentive to maintain their reputation.

Certification of electric equipment

Indeed, the “issuer pays” model turns out to be applicable to other areas of the economy where information is important. For example, certification of electrical equipment and other products for safety is an area that is increasingly important these days. The top U.S. “certification agency” is UL LLC, an organization founded in 1894 as the Underwriters’ Electrical Bureau, and operated until 2012 as the non-profit Underwriters Laboratory.13

UL’s business model is to charge companies with new products to get certification for meeting safety standards, typically promulgated by Underwriters Laboratory, in order to get the UL certification. There are other certification organizations in the United States, such as Intertek Testing Services NA, Inc., based in Illinois. But UL is the leader.

For many products, there’s no legal requirement to have a UL certification, but many larger retailers won’t sell the product without. Certification for products used in the workplace is mandated by OSHA, which publishes a list of approved testing laboratories.14 In addition, the government sometimes mandates that particular products cannot be sold in the United States without UL certification. That was true in 2016 for hover boards, for example, when the CPSC banned any hover board that didn’t have a UL certification.15

As with credit rating agencies, issues regularly arise about the objectivity of UL certification.16 Moreover, as UL has extended its work to certify a wider variety of products, questions have arisen about its capabilities. Nevertheless, the “issuer pays” model in product safety certification seems to be functioning well.

Indeed, the European Union, which on the surface uses a “self-certification” model, seems to be heading towards “issuer pays.” The selfcertification model uses the CE mark, which means that the manufacturer or retailer is taking responsibility that the product meets EU standards.17 But in many product areas the company must also get the approval of what’s known as a “notified body,” which is the equivalent of a certifying authority.18

Unfortunately, the European system has been criticized for being too lax.19 Gradually they have been moving closer to a pure “issuer pays” model, with more products requiring certification by notified bodies.

Rating of journalist organizations

One area where third-party rating is just getting started is the news business. Companies such as Facebook and Twitter have been criticized for allowing too much ”fake news” on their platform—low quality news sources that spread misinformation. On the other hand, if they start exercising too much control, they are accused of censorship and monopoly power.

The obvious solution is for the platforms to use an independent third party. Indeed, we’ve started to see a rise of for-profit companies that rate the reliability of news sources. The leading one so far is NewsGuard Technologies, founded in 2018 by Steven Brill and Gordon Crovitz, formerly publisher of the Wall Street Journal. NewsGuard ranks news sources on nine different criteria, such as “avoids deceptive headlines” and “does not repeatedly publish false content.” 20

The demand for journalistic ratings comes in part from the threat of government regulation. European countries, in particular, have passed laws to control “fake news.”21 Companies such as Facebook, Google, Microsoft, Mozilla, and Twitter have signed onto the European Commission’s voluntary Code of Practice on Disinformation, which commits them to take certain steps to control fake news.22

So far, the NewsGuard business model is “user pays.” As the company says, “NewsGuard’s revenue comes from Internet Service Providers, browsers, search engines and social platforms paying to use NewsGuard’s ratings.” For example, Microsoft is paying a licensing fee to NewsGuard to incorporate the ratings into Microsoft’s Edge browser.23 In addition, individuals can subscribe to the service for a small monthly fee. It’s not clear how many other platforms are paying, especially since the ratings are publicly available.

Over time, platforms may gravitate towards only featuring news sources that get satisfactory grades from at least two independent raters. That opens the possibility of an “issuer pays” model where news sites pay a fee to get rated, perhaps proportional to their web traffic. This has the advantage that the ratings are public and available to everyone.

CONCLUSION

Since the 2008-2009 financial crisis, critics have worried about the biases built into the “issuer pays” compensation model for credit ratings agencies. Now that the Covid-19 crisis has placed the credit markets under great stress, these questions are once again coming to the fore. But as we show in this report, nobody has been able to come up an alternative compensation model that is clearly better. There’s no reason to believe that the issuer pays compensation model will get in the way of the necessary effective and independent third party assessment of default probabilities under extreme uncertainty.

Indeed, in the Information Age, the “issuer pays” approach for credit ratings may serve as a good model for other parts of the economy, because it generates a clear signal. We identified another sector, product certification, where “issuer pays” is the dominant model despite its inherent biases. We also consider whether the “issuer pays” model could be applied to certify the quality of journalist organizations, an exceptionally important problem that has been difficult to solve.

To Open or Not To Open: Educational Equity Under COVID

The Reinventing America’s Schools Project sponsored an engaging discussion entitled “To Open or Not To Open: Educational Equity Under COVID.”

Over 4,000 parents, educators, advocates, funders, journalists, and policy makers registered to hear from experts in teaching, parental engagement, system leadership and health on how to equitably reopen schools in the fall.

Our moderator and panel discussed the health, policy, and budgetary factors school systems should consider before making a decision grounded in educational equity for all students.

The Reinventing America’s Schools Project was glad to sponsor such an important conversation at this time. Thanks to Alma Vivian Marquez, George Parker, Paul Vallas, and Dr. Leana Wen for joining our Deputy Director Curtis Valentine!

Watch here.

Opinion: Bridgeport schools must do more to prepare for fall

Bridgeport Public School students were in trouble before the pandemic shuttered schools in March. Each year, BPS students take the “Smarter Balance” state tests. On the 2019 test, not a single BPS school recorded 50 percent of its students meeting or exceeding expectations for their grade level in reading, with the exception of two select enrollment magnet schools.

At seven BPS schools, fewer than 20 percent of students scored at grade level in reading, with just 10 percent of students proficient at Cesar Batalla School, and just 9.5 percent meeting or exceeding expectations at Luis Munoz Marin Elementary. Scores in math were no better — in many cases, they were worse.

What does this look like when we turn the statistics into living, breathing children? Well, from those seven BPS schools with fewer than 20 percent of students scoring at grade level, the state counted a total of 3,466 student test scores. Of those 3,466 kids, only 444 of them had learned what they should have by that point in their schooling. The vast majority, 3,022 kids, are behind, and had not learned what they need to succeed at more challenging coursework in the next grade.

This spring, the pandemic closed BPS before students could take the state test, to see if they had done any catching up since the previous year. Since 1906, researchers have been studying the “summer slide,” or, the amount of learning students lose over summer when schools are closed. One of the biggest studies in recent times showed that students can forget as much as 25 to 30 percent of what they learned the previous year over the roughly 10 weeks of summer vacation. This year, if schools really do open as scheduled, BPS students will have been out of the classroom for 24 weeks — a solid six months.

In a normal year, there would be no reason to expect the massive numbers of BPS students who are behind would do better in the following grade without some kind of intervention, like tutoring, remedial work in summer school, and so on. In this very abnormal year, with its huge gap in continuous learning, BPS has a heightened responsibility to marshal every available resource to reach its already-behind students and ensure they do everything humanly possible to give them the attention and instruction to which they are entitled.

Read the full piece here.

How Ecommerce Creates Jobs for American Workers and Saves Time for American Families

This past weekend a Wall Street Journal piece quoted me on ecommerce jobs:

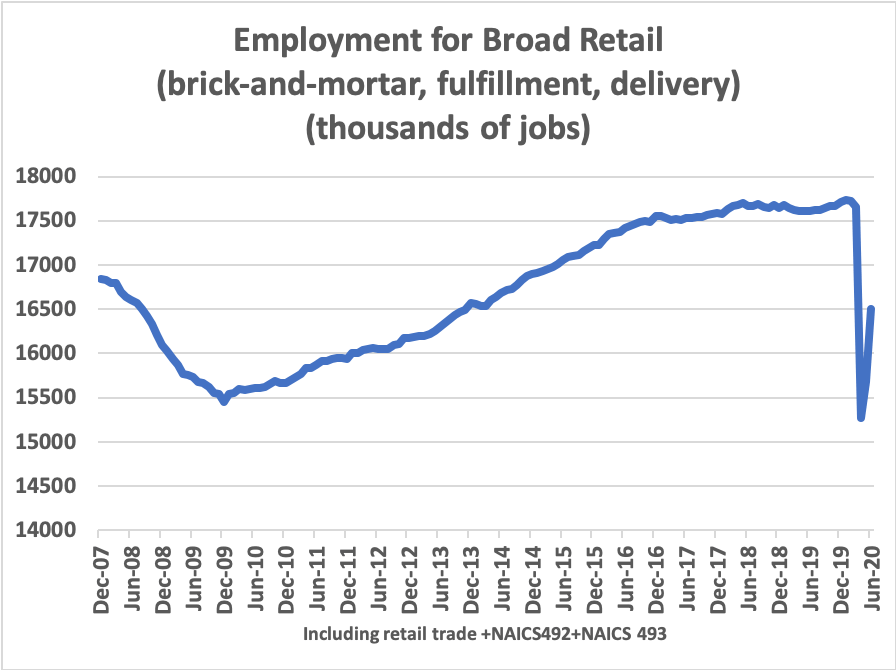

One economist who has looked at these trends has concluded something surprising: When you include all the jobs in fulfillment, delivery, and related roles, e-commerce has created more jobs between 2007 and January 2020 than bricks-and-mortar retailers lost, says Michael Mandel, chief economic strategist at the Progressive Policy Institute, a think tank. Since January, employment in this sector has fallen, but Dr. Mandel believes that as consumer spending recovers, so will employment in this area.

I thought I would give some of the statistical backup. I calculated total jobs in brick-and-mortar plus ecommerce by adding retail trade, couriers and messengers (NAICS 492)(local delivery) and warehousing and storage (NAICS 493)(ecommerce fulfillment). This total was still rising in early 2020, before the pandemic hit, with the peak coming in January 2020.

Between December 2007, the previous business cycle peak, and January 2020, ecommerce industries created 900K more jobs than were lost in brick-and-mortar retail. We can see the total in this chart.

Total jobs went up because unpaid hours that Americans used to spend driving to the mall, parking, wandering through stores, waiting on line to pay, and driving home are now being transferred to the paid sector.

How many hours are being saved? Each year the BLS does a survey called the American Time Use Survey. It shows that average consumer shopping hours per person, excluding groceries and gasoline, fell by 27%, from roughly 144 hours per year in 2007 to roughly 105 hours per year in 2018. Presumably this decline was driven by ecommerce.

The implication: Summed over the whole U.S. population, ecommerce saved American families 10 billion hours per year in 2018.

The conclusion: More jobs for American workers, more time for American families.

Release: In Gig Economy Space, New Report Shines Light on Regulatory Improvements for Independent Workers

Independent workers face a dilemma where they cannot currently receive benefit payments from companies without risking their independent status.

WASHINGTON, D.C. – A new report from the Progressive Policy Institute examines the possibility of creating a way to regulate platforms that would preserve the flexible nature of independent workers and the benefits to our economy at large while continuing to protect both workers and consumers. The flexibility of platforms will play a critical role in helping the U.S. labor market recover more quickly from the COVID recession.

The new report finds that companies that do business with independent workers can’t provide benefits because that would turn them into employees, an outcome that the overwhelming majority of these workers do not want. But independent workers providing benefits for themselves incur a much bigger tax burden than they would face as an employee.

Key findings from the report include:

- According to a recent report from Edelman Research & Upwork, 51% of respondents said there is no amount of money where they would definitely take a traditional job;

- During recessions, unemployment insurance benefits received swell far out of proportion to taxes paid in, as the federal government typically appropriates more money to beef up unemployment insurance;

- One estimate from the Berkeley Research Group concluded that switching the status of app-based drivers to full-time employees would reduce the number of drivers by 80 to 90 percent in California.

The new report identifies four prongs in which there is a ‘better way’ to revamp the current system tax treatment for independent workers: straighten out the current tax code, simplify the dividing line, apply a baseline level of benefits, and implement a cafeteria style plan.

Straightening out the current tax code would require independent workers to deduct healthcare and retirement contributions from the earnings calculation for the self-employment tax. In order to simplify the dividing line, an independent worker would have to reach a certain number of hours contracting with a particular company or platform, then the worker would be entitled to a required set of tax-advantaged benefits.

To apply a baseline level of benefits, companies would be able to offer benefits to independent contractors without worrying that they would be reclassified as employees at either the state or federal level. The cafeteria plan would allow independent workers to choose from a variety of pre-tax benefits, including health insurance, paid time off, and retirement savings.

Policy recommendations include:

- Construct a new regulatory framework that explicitly recognizes a middle ground of independent workers who can receive benefits from the (multiple) companies they contract with;

- Straighten out the tax treatment of benefits so that independent workers are on a level playing field with employees;

- Require a baseline level of benefits and protections for independent workers, including a cafeteria style plan;

- Install a uniform national standard for determining who is an independent worker.

“A separate and important question is whether the new regulatory regime would be opt-in or mandatory,” said author Michael Mandel, the chief economic strategist at PPI. “If companies do not opt in, they would remain subject to existing legal tests for determining worker classification.”

Regulatory Improvement for Independent Workers: A New Vision

One of the biggest productivity advances in recent years has been the use of platforms to connect buyers and sellers at lower cost. Platforms offer less rigid contractual arrangements, expanded earnings opportunities for workers and access to essential goods and services for underserved communities. Overall, platforms generate win-win economic activity which benefits everyone.

The flexibility of platforms will play a critical role in helping the U.S. labor market recover more quickly from the Covid recession. In most economic recoveries, companies have been apprehensive about making the commitment to hire given lingering economic uncertainty. That has typically made employment a lagging indicator in recoveries. By contrast, platforms will make it easier for workers to scale up hours worked gradually as the economy expands, which will boost consumer spending and demand, which will in turn boost employment.

The big question, though, is how to regulate platforms in a way that preserves the flexible nature of the work and the benefits to our economy at large, while continuing to protect both workers and consumers. The Progressive Policy Institute believes strongly in the importance of regulation for a well-functioning market economy. Yet we have long advocated for “regulatory improvement” as essential for accelerating growth and job creation.

Regulatory improvement is very different from deregulation. Too many sectors of the economy have overlapping and contradictory layers of regulation that get in the way of productivity gains and rising incomes. At the same time, there may be parts of the economy where new rules are necessary. In this case, platform businesses need to step up and provide a baseline level of benefits to their workers.

The labor market, in particular, is struggling with a 20th century regulatory framework imposed on a 21st century economic structure. The first 1099 was issued in 1918 and the first W-2 in 1944. To this day the labor market is artificially divided into “employees” and “independent workers”, including freelancers, sole proprietors and other self-employed workers. The dividing line is quite complicated and, in some cases, almost impossible to understand, with different federal and state agencies following different rules for establishing the dividing line. This patchwork of conflicting regulations creates enormous business uncertainty, reducing the incentive to create new work opportunities.

In the current regulatory framework, workers classified as “employees” are subject to a completely different regulatory regime than independent workers, including rules for scheduling and hours worked, working conditions, minimum wages and who pays Social Security and Medicare taxes. Employees are subject to employers’ control in every aspect of how they do the job, which for many low-income workers means shift work tied to a single company, which sets the exact hours. Employees typically get certain benefits, such as workers compensation and unemployment insurance, which are generally paid for by payroll taxes, and possibly access to other benefits, such as group life insurance, defined contribution retirement plans, and employer-sponsored health insurance or health savings accounts (HSAs).

Independent workers have a unique flexibility that employees do not enjoy at all. In the same survey, 51% of respondents said there is no amount of money where they would definitely take a traditional job. Part of the explanation may be that independent contractors simply aren’t able to work under the terms of normal employment; in fact, 46% say they could not have a traditional job due to personal circumstances (e.g., health or caregiving duties).

But in exchange, independent workers, almost by definition, are not allowed to get benefits from the companies that they do business with. As an IRS publication states:

Businesses providing employee-type benefits, such as insurance, a pension plan, vacation pay or sick pay have employees. Businesses generally do not grant these benefits to independent contractors.

Unfortunately, the current tax system systematically penalizes independent workers who try to provide their own benefits and companies that want to help these workers maintain flexibility while accruing appropriate benefits or protections. For example, as we explain below, most independent workers have to pay FICA taxes on the money they contribute to their tax-deferred Individual Retirement Accounts (IRA), Simplified Employee Pensions (SEP) or solo 401k accounts. By comparison, the contribution of employers to employee retirement accounts is exempt from both employer and employee FICA taxes. This saving can be worth thousands of dollars. The same or similar problems show up with other benefits as well.

This puts independent workers into a catch-22 situation. The companies that they do business with can’t provide benefits because that would turn them into employees, an outcome that the overwhelming majority of these workers do not want. But independent workers providing benefits for themselves incur a much bigger tax burden than they would face as an employee.

There are two solutions to this problem for independent workers. One is to double down on the historical dichotomy between employees and independent workers and make the distinction even more rigid. This “Procrustean Bed” solution is best exemplified by which imposes rigid tests on who can be classified as an independent contractor. Basically, it forces companies to turn many of their independent contractors into employees, which would lead to the loss of these workers’ flexibility and control over their hours and who they can work for. In the gig economy space, this would almost certainly mean set schedules and the inability to work on more than one platform. Minimum wage rules and other employment regulations would lead to reduced service at certain times of day or in certain geographical areas.

The other alternative is to improve the position of independent workers by creating a new regulatory regime that extends them important new benefits, while still allowing the flexibility that self-employed workers choose.

This new regulatory regime would have several important features.

- It would straighten out the tax treatment of benefits so that independent workers are on a level playing field with employees.

- It would require a baseline level of benefits and protections for independent workers, including a cafeteria style plan with a menu of options for workers to choose what makes the most sense for them.