FACT: The number of extremely poor people has fallen by two-thirds since 1990.

THE NUMBERS: Number of people in extreme poverty* in Pakistan –

2018 10.5 million (5% of the population)

2010 16.8 million (9% of the population)

2000 48.6 million (33% of the population)

1990 70.1 million (65% of the population)

* At or beneath the “extreme poverty” line is defined by the World Bank, at $2.15 per day, PPP basis, in constant 2017 dollars. World Bank estimates; 2018 is the most recent available year.

WHAT THEY MEAN:

Looking back at the post-Cold War/globalization era, what should we see first? Four obvious nominees: the launch of the internet and the creation of the digital world; the China boom; the acceleration of climate change and biodiversity loss; an extended and historically anomalous time of peace among great powers? Here’s a fifth and less visible candidate: the best period in human history for the very poor.

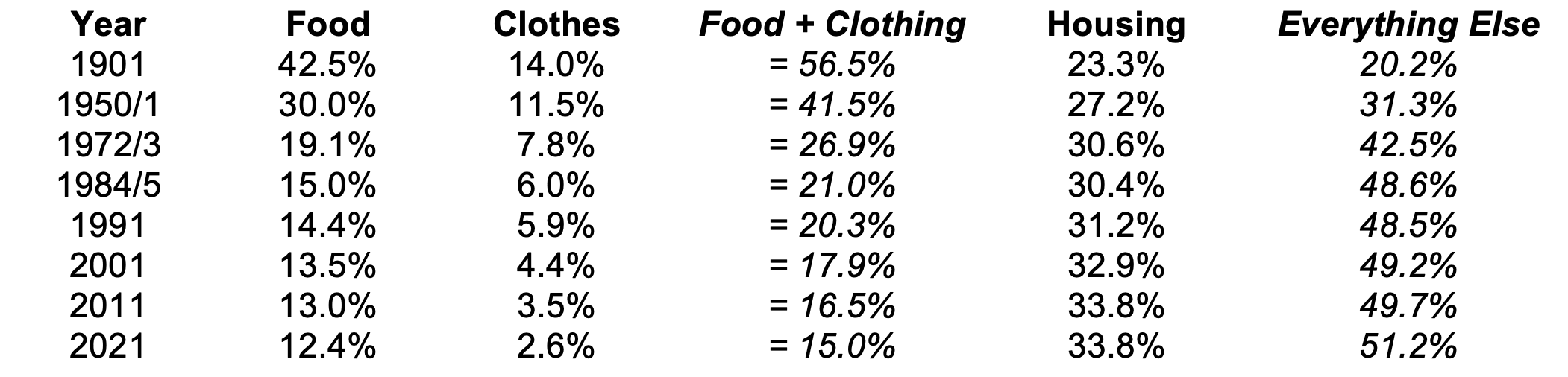

The World Bank’s definition of “absolute” or “extreme” poverty is life at “$2.15 per person per day in constant 2017 dollars as measured in purchasing-power parities.” This is not necessarily “income,” but consumption of a minimal level of food, clothing, and shelter in very poor countries. To illustrate: estimates of annual per capita income in Burundi, currently thought to be the world’s poorest country, range from $700 to $865. This is $1.92 to $2.37 per day, essentially the $2.15 level. A Bank database calculates the cost of a minimally “energy-sufficient” diet at $1.10 per day, about half the typical daily spending of a rural Burundian. A “nutrient-adequate” diet, at $2.93 per day, would be out of reach.

Just after the breach of the Berlin Wall in 1990, about 2 billion of the world’s 5.3 billion people lived this sort of life. A bit more than half, 1.055 billion by the Bank’s estimate, lived in East and Southeast Asia. Another 563 million were close by in South Asia, among them 70 million of Pakistan’s then 115 million people. Sub-Saharan Africa counted 271 million, Latin America and the Caribbean 73 million, just past-Soviet Eastern Europe and Central Asia 15 million, and the Middle East and North Africa 14 million. Over the next three decades:

1990-2000: In the decade of democracy promotion, trade liberalization, and the early Internet, the count of extremely poor people fell by about 200 million as world population grew by 800 million. This left 1.8 billion extremely poor, or 29% of the world’s 6.1 billion people.

2000-2010: As the China boom and its gravitational effects in Southeast Asia, South America, and Africa took hold, another 650 billion moved above the line. Extreme poverty counts fell by two-thirds in East Asia and Southeast Asia, and by half in Latin America, the Middle East, Eastern Europe and Central Asia, to end at 16.9% of world population in the midst of the financial crisis of 2010.

2010-2019: In the decade just passed, extreme poverty fell by another 350 million, nearly vanishing in East and Southeast Asia — down 98% from the 1.06 billion of 1990 to 24 million — and showing the largest absolute-number drop in South Asia (from 430 million to 157 million; as Pakistan’s population topped 230 million, the number of extremely poor Pakistanis fell to 10.5 million). = The global total just before the COVID-19 pandemic was 649 million, or 8.4% of a worldwide 7.8 billion people.

To 2023: The COVID pandemic interrupted this steady downward curve, but perhaps only temporarily. The Bank’s early estimate is that 70 million people fell back into extreme poverty in 2020, but that by last year the total was nearly back to the levels of 2019. With estimates for 2020-22 still tentative, the numbers look like this:

2022 ~655 million of 8.0 billion?

2020 ~714 million of 7.9 billion?

2019 649 million of 7.8 billion

2010 1127 million of 7.0 billion

2000 1782 million of 6.1 billion

1990 1995 million of 5.3 billion

To move above an extreme-poverty line, of course, is to escape destitution and chronic hunger, but to remain poor. But poverty at higher income levels has also fallen, if a bit more slowly — from 56% of the world’s people living on $3.65 per day or less in 1990, for example, to 23% as of 2019%; turning back to Pakistan, 91% lived below this level in 1990, and 40% now. This suggests not only a worldwide reduction in extreme deprivation and chronic malnutrition, but a broader shift toward lower-middle-class life. Social indicators bolster this impression, with world infant mortality down by two-thirds since 1990, girls’ literacy in low-income countries up by half, from 48% to 69%; and life expectancy up 7 years worldwide and 13 years in low-income countries.

Searching for a verdict on the post-Cold War world, then, the creation of the digital world, the growth of Chinese power and industry, environmental stresses, and the era’s then-unappreciated and now-vanishing geopolitical calm remain strong candidates. But the escape of a third of the world’s people from destitution easily stands with them.

Further Readings

Worldwide data and analysis:

The World Bank’s center for poverty data.

Our World in Data has poverty totals and rates by country from 1967 through 2021.

And the World Bank’s review of poverty in Burundi, 2022.

Two questions:

Why? Explanations for the decline of poverty — extended peace, lower trade barriers and more open markets for poor-country goods, dissemination of new medicines and technologies, better basic education and public health policies — seem mostly complementary rather than contradictory or “enough in itself.” A nominee for “most important,” though, comes from economist Charles Kenny, whose prescient Getting Better: Why Development is Succeeding and How We Can Improve the World Even More (2012) noticed the fall in poverty early and views the core issue as growing intellectual consensus in developing-country governments on good and relatively low-cost policies:

“Poor countries and poor people aren’t stuck in the nightmare of ever-growing and unsupportable population, living on bare subsistence. Instead, those countries with the lowest quality of life are making the fastest progress in improving it — across a range of measures including health, education, and civil and political liberties. The progress is the result of the global spread of technologies and ideas – technologies like vaccination, and ideas like ‘you should send your daughter to school.’”

Read Kenny’s Getting Better.

And can this continue? Some factors suggest it should. Extreme poverty now is concentrated in three ways: (a) in remote rural areas as opposed to cities, where flows of young people to cities and improved infrastructure can help; (b) in sub-Saharan Africa, and the rate of extreme poverty has fallen from 53% to 35% since 1990, though rapid population growth has kept the total number high, and growth and policy trends seem likewise mostly positive, and (c) in conflict zones as opposed to peaceful regions. Others are less promising: a world landscape of high great-power tension, weaker commitment by major economies to openness and integration, and rising economic costs of climate change for poor countries may not be so severe as to reverse the positive trends of 1990-2019, but is likely less friendly to the poor.

Views from Pakistan:

The Pakistan Institute of Development Economics in Islamabad reviews trends over the past two decades (urban vs. rural, by province, children, income vs. nutrition, etc.).

Hina Shaikh at the International Growth Centre looks at next steps.

And a World Bank snapshot.

The role of trade? Three perspectives:

Carolyn Freund and Sanchez-Paramo on trade, poverty, and pro-poor reform, drawn from close analysis of trade impacts in Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Brazil, Mexico, and South Africa.

PPI’s Ed Gresser last year on renewal of the Generalized System of Preferences, the main U.S. trade preference program for low- and middle-income countries (quick summary: renew and update the GSP, but don’t overdo new eligibility rules).

And the potential of intra-African trade integration to accelerate current growth in per capita income in low-income African countries.

ABOUT ED

Ed Gresser is Vice President and Director for Trade and Global Markets at PPI.

Ed returns to PPI after working for the think tank from 2001-2011. He most recently served as the Assistant U.S. Trade Representative for Trade Policy and Economics at the Office of the United States Trade Representative (USTR). In this position, he led USTR’s economic research unit from 2015-2021, and chaired the 21-agency Trade Policy Staff Committee.

Ed began his career on Capitol Hill before serving USTR as Policy Advisor to USTR Charlene Barshefsky from 1998 to 2001. He then led PPI’s Trade and Global Markets Project from 2001 to 2011. After PPI, he co-founded and directed the independent think tank Progressive Economy until rejoining USTR in 2015. In 2013, the Washington International Trade Association presented him with its Lighthouse Award, awarded annually to an individual or group for significant contributions to trade policy.

Ed is the author of Freedom from Want: American Liberalism and the Global Economy (2007). He has published in a variety of journals and newspapers, and his research has been cited by leading academics and international organizations including the WTO, World Bank, and International Monetary Fund. He is a graduate of Stanford University and holds a Master’s Degree in International Affairs from Columbia Universities and a certificate from the Averell Harriman Institute for Advanced Study of the Soviet Union.

Read the full email and sign up for the Trade Fact of the Week