FACT: Vanilla, a poorly chosen synonym for “boring.”

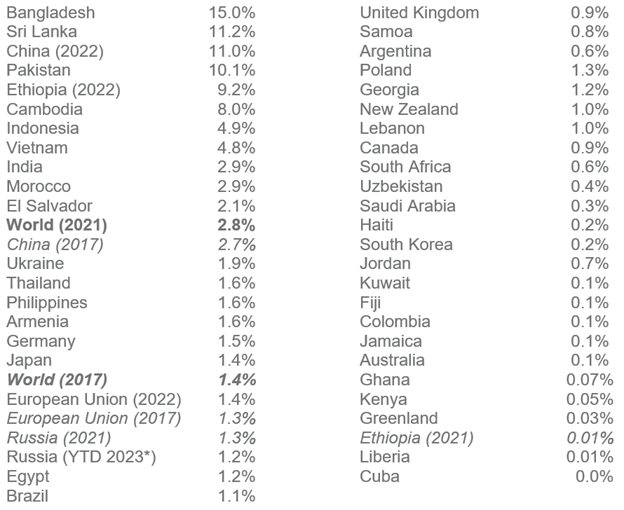

THE NUMBERS: Annual production of —

Sugar 177,000,000 tons

Cacao beans 2,900,000 tons

Vanilla 7,614 tons

WHAT THEY MEAN:

Merriam-Webster’s two meanings for “vanilla,” in its adjective form:

1. Flavored with vanilla

2. Lacking distinction; synonyms plain, ordinary, conventional

How did vanilla get a reputation like this? A look at the facts argues pretty strongly that vanilla isn’t boring, plain, or conventional at all; rather it is exotic and expensive, hard to find and even harder to grow, and maybe a bit scandalous. You be the judge:

Origins and chemistry: Like chocolate, vanilla is native to Mexico and was originally cultivated around Vera Cruz. Popular among the Aztec nobility as a flavoring for high-end drinks and sweets, it comes from the treated “pod” of an orchid pollinated by local bees and hummingbirds. The main active ingredient is a phenol-based chemical compound informally termed “vanillin.”

“Globalization” and modern production: Vanilla cultivation outside Mexico is challenging because no one so far has discovered another natural pollinator. Nonetheless, the 19th-century French empire found an alternative way to do it: the hand-pollination technique invented in 1841 by an enslaved 12-year-old farmhand named Edmond Albius on Reunion (then a French Indian Ocean possession, now an overseas department), and introduced to Madagascar after the colonial conquest in the 1890s. Dutch colonials later introduced the same technique to Indonesia (or more specifically, the southern Sunda island group). Together Madagascar and Indonesia now produce about half of the world’s roughly 7,600 tons of natural vanilla each year. Mexico adds about 500 tons; other outposts in Papua New Guinea, Tahiti, and Uganda account for most of the rest. To put this in context, each year the world’s farmers produce 25,000 tons of sugar, and 500 tons of the cocoa-bean precursor to chocolate, for every ton of natural vanilla.

Cost: Scarcity and difficulty of production make vanilla, in most years, the world’s second-most-expensive agricultural product. (As measured by price per kilo.) Saffron at $500/kilo is easily the priciest; vanilla beans usually come at about $50 per kilo depending on annual marketing and harvest. Cardamom sometimes puts up a fight for second, though.

Trade: Americans bought about a quarter of the world’s 2022 vanilla crop, or 1,989 tons in total. Most — 1,448 tons — came from Madagascar, followed by 207 tons of Indonesian vanilla (Flores, Sumba, west Timor) and 172 tons from Uganda making up most of the rest. Other suppliers included 39 tons from Papua New Guinea, 36 tons from India, 24 tons from the Comoros Islands, and 0.5 tons from Tahiti. The harvested, dried, and washed pods arrive in cans, often groups of six weighing 48 kilos, mostly by air cargo. Total import value was $345 million — about two minutes worth of America’s year-long $3.27 trillion in total goods imports — and vanilla, like most spices, has no U.S. tariff.

Sexual reputation: Vanilla is sometimes said, maybe most frequently by vanilla marketers, to have a natural aphrodisiac effect. Though obviously a convenient sales pitch, this may have a factual base at least in the case of some rodents. A 2012 paper (Maskeri et al.) from the Pharmacognosy Journal: “Vanillin in the dose of 200 mg/kg demonstrated aphrodisiac properties in male wistar rats.”

Real vs. artificial: The 7,600-ton total output is far too little to meet the world’s flavoring and aromatic needs. Most vanilla used in sweets and cooking, therefore, is not the natural hand-pollinated stuff but artificial “vanillin.” This is the same active molecule, but extracted by chemistry-industry professionals in five factories — three in China, one in France, one in the United States — and not from delicate orchids but “wood pulp.” a substance with a more convincing claim to plainness, ordinariness, and conventionality than vanilla itself.

FURTHER READING

Merriam-Webster’s “vanilla” site — see uninspiring adjective definitions, also scroll down for the startling etymology.

Origins and production:

The origin: NPR reports on Mexico’s troubled vanilla industry.

The inventor: Child laborer, enslaved farm-worker, and agricultural revolutionary Edmond Albius invented hand-pollination of vanilla orchids and so founded the modern global vanilla industry.

… and Reunion, now an overseas French Department, pitches the product 180 years later.

The top producer: Le Monde on an oversupply crisis this summer in Madagascar.

… and direct to Madagascar’s GEM (Groupement des Exporteurs de Vanille de Madagascar).

And the University of Florida explains attempts to grow it here.

Cost:

A list of the world’s most expensive (per-kilo) ag products places vanilla second after saffron.

Sex & science:

NIH explains the chemical structure of vanillin.

A modern-day marketer enthusiastically details vanilla’s supposed aphrodisiac effects.

… and a scientific paper provides some backup, at least for “male wistar rats.”

And another thing:

“Chocolate” is originally an Aztec word, recalling the cocoa bean’s original Native American cultivators. (The cocoa tree’s modern scientific name, Theobroma cacoa, means food of the gods” and is one of the original Linneus’ species-names.) Chocolate’s first documented use, confirmed by archeologists in the early 2000s, was about 2,600 years ago in Guatemala. Nineteenth-century colonial entrepreneurs, mainly Brits in contrast to the French and Dutch vanilla-propagators, introduced cocoa trees to West Africa. This region remains the main cocoa-bean producer, particularly centered in Ghana and Cote d’Ivoire, and accounts for about 70% of modern cocoa-bean production. Other production spreads around the Caribbean littoral, Indonesia, and Papua New Guinea. The Ghana Cocoa Board.

ABOUT ED

Ed Gresser is Vice President and Director for Trade and Global Markets at PPI.

Ed returns to PPI after working for the think tank from 2001-2011. He most recently served as the Assistant U.S. Trade Representative for Trade Policy and Economics at the Office of the United States Trade Representative (USTR). In this position, he led USTR’s economic research unit from 2015-2021, and chaired the 21-agency Trade Policy Staff Committee.

Ed began his career on Capitol Hill before serving USTR as Policy Advisor to USTR Charlene Barshefsky from 1998 to 2001. He then led PPI’s Trade and Global Markets Project from 2001 to 2011. After PPI, he co-founded and directed the independent think tank Progressive Economy until rejoining USTR in 2015. In 2013, the Washington International Trade Association presented him with its Lighthouse Award, awarded annually to an individual or group for significant contributions to trade policy.

Ed is the author of Freedom from Want: American Liberalism and the Global Economy (2007). He has published in a variety of journals and newspapers, and his research has been cited by leading academics and international organizations including the WTO, World Bank, and International Monetary Fund. He is a graduate of Stanford University and holds a Master’s Degree in International Affairs from Columbia Universities and a certificate from the Averell Harriman Institute for Advanced Study of the Soviet Union.

Read the full email and sign up for the Trade Fact of the Week