FACT: PPI has published 171 papers, posts, op-eds, and Trade Facts so far this year.

THE NUMBERS:

Publication average, 2022: One every two days

WHAT THEY MEAN:

With staff preparing for holiday travel, in lieu of a regular Trade Fact we have some reading ideas for the long weekend: (a) highlights from PPI’s papers and posts over the past year; (b) four not-quite-canonical classics for the ambitious reformer already thinking about 2023; and (c) four book recs for sidewise, bottom-up, and overhead views of economic policy, trade, and technology:

1. Five reads from PPI:

- Bill Galston & Elaine Kamarck, in The New Politics of Evasion, look at swing voters, the American political system, and liberalism in 2022.

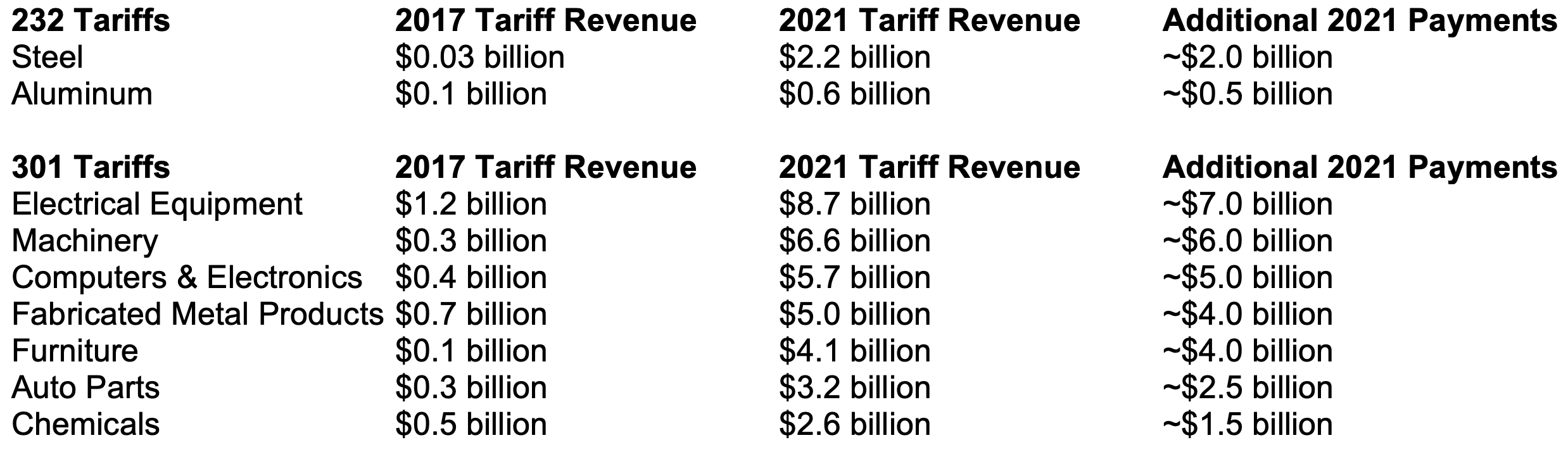

- Ed Gresser on the U.S. tariff system, mostly ineffectual as a job-preserver but quite good at taxing the shoes and clothes low-income families and single moms buy.

- Paul Bledsoe’s prescient case against the European Union’s dangerous reliance on Russian gas (December 2021) and better alternatives for European security and emissions reduction.

- Malena Daley cautions against antitrust over-enthusiasm in the tech world.

- Arielle Kane examines the lessons of COVID-19 and preparation for the next pandemic.

- And Taylor Maag and Gresser suggest replacing Trade Adjustment Assistance with all-worker-eligible supports.

2. The timeless wisdom of the classics:

At last! That long-awaited sub-Cabinet nomination (or alternatively Congressional subcommittee chair, Chief Negotiator assignment, White House Senior Director position, etc.) has finally come through. You’re memorizing the oath and preparing to change the world. Some lesser-known classics can help you see what’s ahead:

The Tactics of Reform — As you get started, remember that while issues and political coalitions constantly shift and change, the challenges of reform are always the same. As medieval knights must triumph over ogres, dragons, and giants, modern reformers must overcome entrenched defenders of the status quo, ossified procedures and vicious though pointless bureaucratic rivalries, and ruthlessly ambitious subordinates who care more about getting your job than the vision. Mervyn Peake’s Gormenghast books (1946-1959) are a sort of parable illuminating their likely tactics, from passive aggression and embittered moping to arson, defenestration, and insincere proposals for incremental change.

The Art of Persuasion — It’s a few months later. You’ve set out a vision and called in the ‘stakeholders’ … somehow logic, eloquence, and appeals to conscience and interest don’t seem quite enough. For additional persuasive power, try Darrell Huff’s How to Lie with Statistics (1954).

The Vigorous Leader — A year in. Reform is stalled, and your superiors in the administration (alternatively the Committee chair/your Cabinet officer/etc.) seem to be hearing more complaints than applause. Time for a stronger approach. Han Fei-tzu’s The Five Vermin (240 BC) helps you play to win, by silencing … forever … the greedy interest groups, preening intellectuals, shirkers, obstinate petty officials, and big-mouths of all sorts who are in your way.

The Perversity of Human Nature — It’s over. How could your steadfast supporters, tough but principled negotiating partners, and loyal opposition have behaved this way? Try ibn Marzuban’s The Book of the Superiority of Dogs Over Many Who Wear Clothes (920)

3. And four new (or new-ish) books on global-economy-related matters:

Brad DeLong’s Slouching Towards Utopia: An Economic History of the 20th Century (2022) on big-think economists, their visions, and their equivocal successes.

Stephanie Elizondo-Griest – All the Agents and Saints: Dispatches from the Borderlands (2017), on business, daily life, and crossings at the U.S.-Canada and U.S.-Mexico borders.

Jan-Werner Muller’s What is Populism (2016, still relevant though) on the origins and ideas of populist-nationalist movements in the U.S., Europe, and Latin America.

David Kaye’s Speech Police: The Global Struggle to Govern the Internet (2019) on platforms, users, international organizations, national laws, and the future of cyberspace.

FURTHER READINGS:

Our Trade Fact launch edition, on the case for liberalism in darkening times.

Happy Thanksgiving from all of us to PPI’s supporters, readers, and friends at home and abroad.

ABOUT ED

Ed Gresser is Vice President and Director for Trade and Global Markets at PPI.

Ed returns to PPI after working for the think tank from 2001-2011. He most recently served as the Assistant U.S. Trade Representative for Trade Policy and Economics at the Office of the United States Trade Representative (USTR). In this position, he led USTR’s economic research unit from 2015-2021, and chaired the 21-agency Trade Policy Staff Committee.

Ed began his career on Capitol Hill before serving USTR as Policy Advisor to USTR Charlene Barshefsky from 1998 to 2001. He then led PPI’s Trade and Global Markets Project from 2001 to 2011. After PPI, he co-founded and directed the independent think tank Progressive Economy until rejoining USTR in 2015. In 2013, the Washington International Trade Association presented him with its Lighthouse Award, awarded annually to an individual or group for significant contributions to trade policy.

Ed is the author of Freedom from Want: American Liberalism and the Global Economy (2007). He has published in a variety of journals and newspapers, and his research has been cited by leading academics and international organizations including the WTO, World Bank, and International Monetary Fund. He is a graduate of Stanford University and holds a Master’s Degree in International Affairs from Columbia Universities and a certificate from the Averell Harriman Institute for Advanced Study of the Soviet Union.

Read the full email and sign up for the Trade Fact of the Week