FACT: Mexico is now the principal source of illicit fentanyl and methamphetamines sold in the U.S.

THE NUMBERS: U.S. deaths by drug overdose –

2021 total |

107,500* |

Opioids |

73,400 deaths among 9.5 million users |

Psychostimulants |

32,500 deaths among 2.6 million users |

Cocaine |

26,000 deaths among 5.2 million users |

Heroin/other opiates |

8,000 deaths among 0.9 million users |

* Mortality from overdoses from the Centers for Disease Control; user totals from HHS’ Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Many overdose deaths involve use of combinations of drugs, so overdoses measured by individual substances often double- or triple-count.

WHAT THEY MEAN:

After two decades of steady escalation, drug overdoses caused over 107,000 premature deaths in the United States last year. This was more than double the 41,500 overdose fatalities of 2012 and six times the 17,400 recorded in 2000. Or, alternatively, it is more than the combined total of U.S. deaths to automobile accidents (38,800 in 2020, 42,400 in 2021) and homicides (24,600 in 2020, likely higher in 2021).

Four classes of drugs, often in combination, account for most of these overdoses: synthetic opioids such as fentanyl, whose very high “purity” and variable chemical content make them especially dangerous; “psychostimulants” such as methamphetamines; cocaine; and heroin along with other natural or semi-synthetic opiates refined from naturally grown opium poppies. The Drug Enforcement Administration’s most recent “Annual Drug Threat Assessment” report, released in early 2021, suggests that (a) most of these products are imported, and (b) supply chains for opioids and amphetamines have changed substantially over the past decade and now center on Mexican production and land transport. A precis:

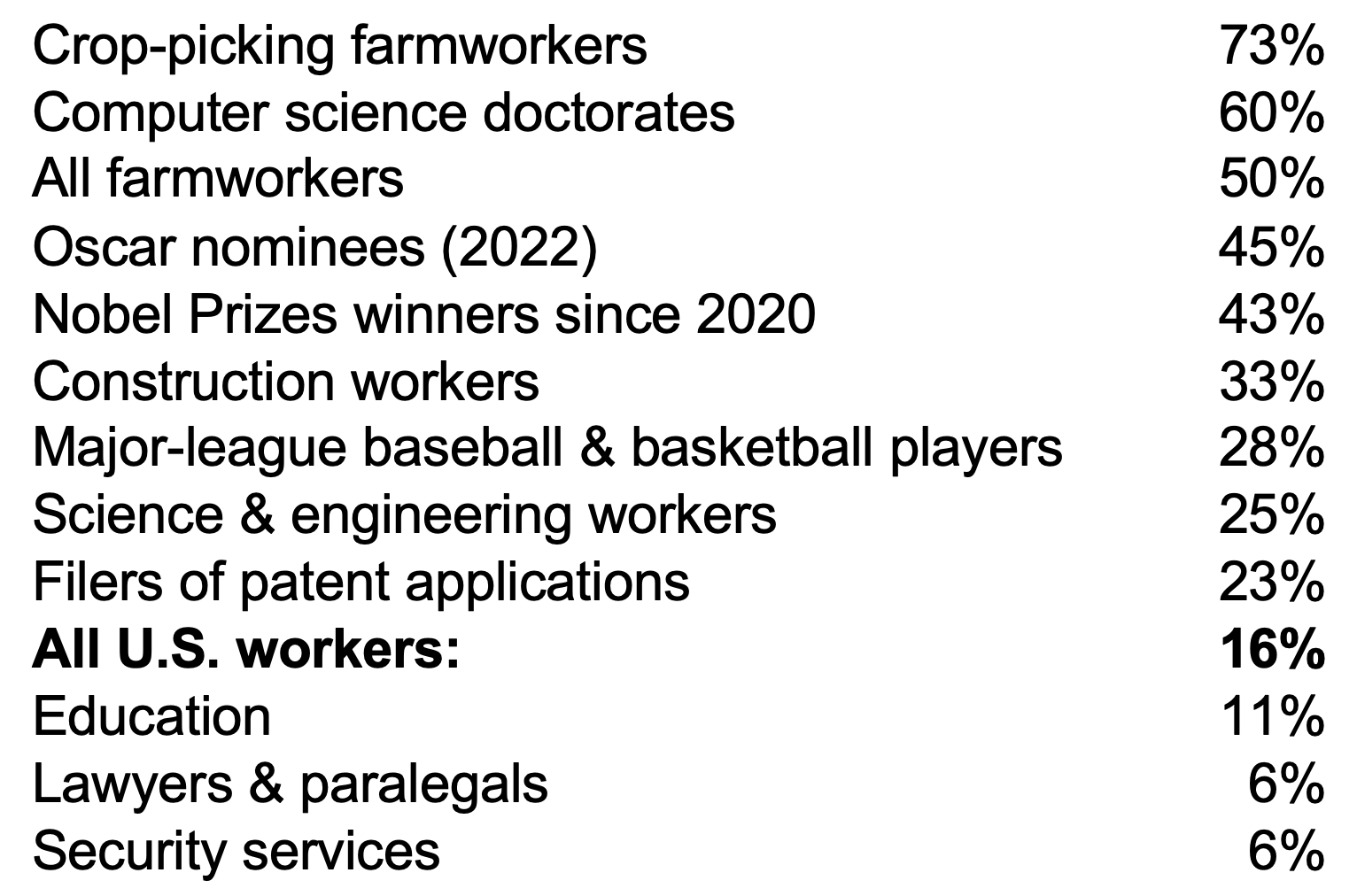

1. Opioids and opiates: A decade ago, fentanyl was mostly made in China and (being very light and cheap to transport) shipped to the U.S. via air cargo. Use of this from-China-by-air route has sharply declined since 2019, however. Most U.S.-consumed fentanyl is now produced in Mexico and moved to the U.S. by land. DEA’s report suggests a complex and adaptable precursor-chemical “supply chain,” with the relevant chemicals “primarily from sources originating in China, including purchases made on the open market, smuggling chemicals hidden in legitimate commercial shipments, mislabeling shipments to avoid controls and the attention of law enforcement, and diversion from the chemical and pharmaceutical industries.” Heroin production appears simpler in the DEA report; about 92% is from Mexico, refined from locally grown opium.

2. Psychostimulants: The methamphetamine supply system has likewise evolved over the past decade, though in this case away from local U.S. lab production. As with heroin, “most of the methamphetamine available in the United States is clandestinely produced in Mexico,” using precursor chemicals purchased from China and India. As with opioids and heroin, the finished products travel mainly by land.

3. Cocaine: Coca leaf is grown and refined into cocaine principally in Colombia and secondarily in Bolivia and Peru. DEA believes total cocaine production is around 1,900 tons per year. Cocaine trafficking routes appear to have remained stable over the last two decades, with cocaine transported in smuggling boats and planes, or using cargo containers, through the Caribbean with smaller quantities arriving by land through Central America and Mexico.

FUTURE READINGS:

CDC’s grim estimates of death by drug overdose in the United States, 2000-2021, summarized by year:

| 2021 | 107,500 |

| 2020 | 92,500 |

| 2019 | 71,100 |

| 2016 | 63,600 |

| 2012 | 41,500 |

| 2000 | 17,400 |

And the numbers in detail by year and substance.

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration has tables for use of narcotics, abuse of prescription drugs, marijuana, alcohol and tobacco use.

The White House releases the 2022 National Drug Control Strategy, including health and overdose prevention, data improvement, DEA and CBP funding, anti-money laundering programs, and international police coordination.

And DEA’s 2020 National Drug Threat Assessment reviews use, production, and trade of narcotics.

And three global economy context questions:

(a) How large is the international narcotics trade? A 2019 RAND study estimates that in 2016 Americans were spending $150 billion on narcotics. This total included $50 billion on marijuana and $100 billion on heroin, cocaine, and methamphetamines, but did not venture a guess on opioids. Accepting RAND’s estimate for the sake of argument, a guess at the value of the imports would require understanding the markup from border to distributor to retail. As a guidepost, the National Coffee Association put U.S. consumer spending on coffee (also almost entirely imported) at $74 billion, or about 12 times that year’s $6 billion in coffee imports. A 10:1 markup for heroin, cocaine, and amphetamines would suggest an import value of around $10 billion, but presumably a criminal business’ markup would have to be much higher. At 20:1, a figure of $100 billion in U.S. retail spending on narcotics would imply $5 billion in import value, the equivalent of about 1 percent of the $385 billion in legitimate imports from Mexico in 2021, and not far from the value of total U.S. coffee imports. Obviously the 20:1 figure is arbitrary and could be quite different, and may also vary by narcotics type.

(b) How large is the criminal economy? On a world scale, a 2017 paper by the DC-based Center for Global Financial Integrity guessed at a total of $426 billion to $651 billion for illicit drug trade as of 2014, including both intra-country and cross-border transactions, as part of a larger $1.8-$2.2 trillion global shadow economy. (The other elements include counterfeiting, human trafficking, illegal wildlife/fishery/logging exports, and other illicit activities.) Cocaine, amphetamines, opiates and opioids accounted for about 60% of the illegal drug business, and marijuana and hashish-type products 40%. The ~$2 trillion estimate, if correct, would have been about 2.5% of that year’s $77 trillion global GDP.

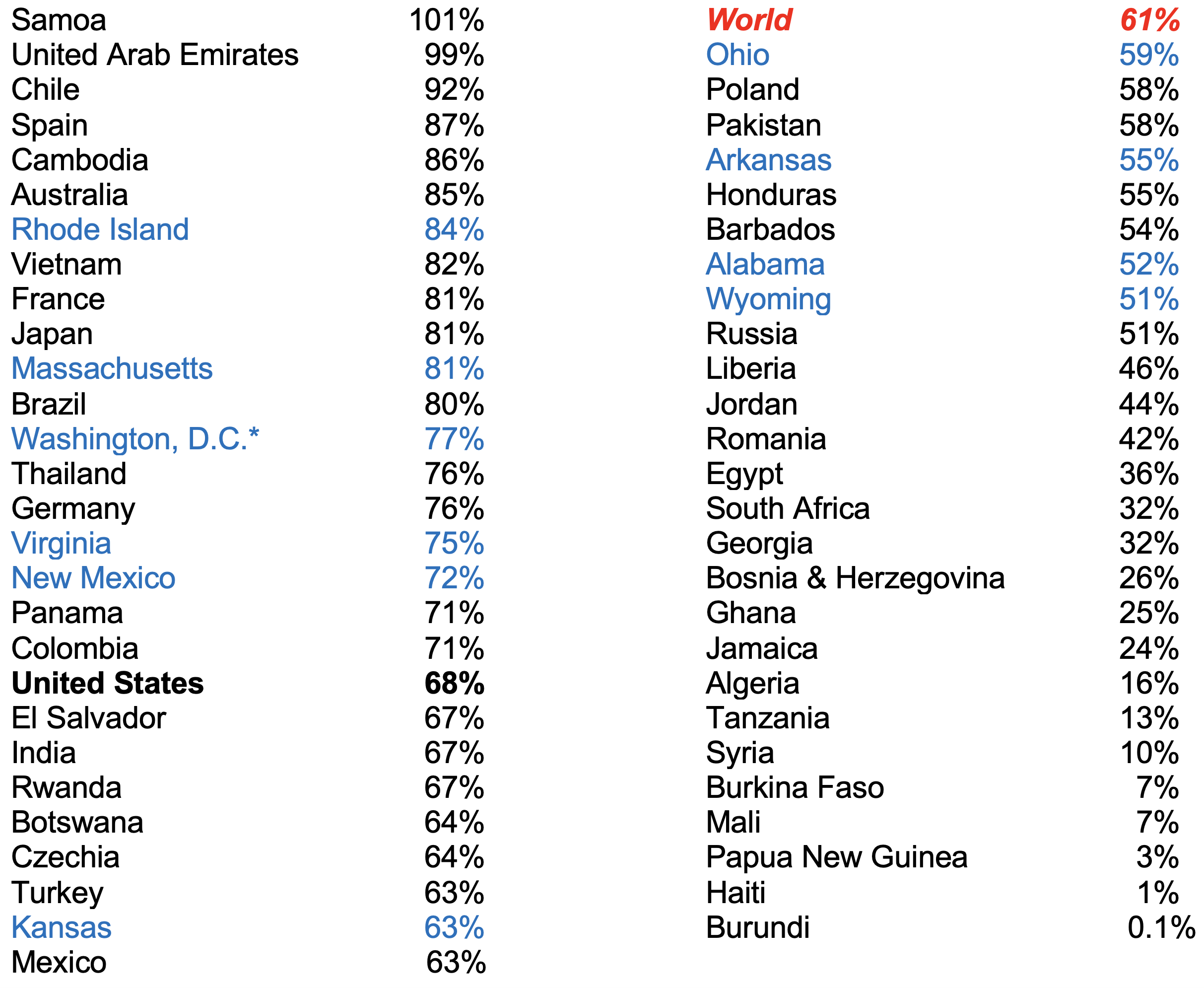

(c) How many drug users are there, and which countries are the largest narcotics markets? UN’s Office on Drugs and Crime’s annual World Drug Report reviews production, transport, health, and other policy matters, and also estimates users counts worldwide. Their most recent guesses: 209.2 million users of cannabis, 61.3 million of opioids, 34.1 million of amphetamines and other stimulants, 31.1 million of opiates, and 21.5 million of cocaine. The analysis of use in UNODC’s 2022 report covers regions rather than countries, but suggests (though not stating explicitly) that the U.S. is the world’s largest narcotics market and largest importer: “North America” is the largest market for cocaine and amphetamines, and at par with Asia for opioids. By population, comparing HHS user estimates for the U.S. to the UN’s worldwide estimates, American narcotics use seems slightly above the world average rate for amphetamines (2.6 million of the UN’s 34.1 million users), below the average for heroin and other opiates, and well above average for fentanyl-type opioids and cocaine. Read more in the UNODC’s World Drug Report 2022.

ABOUT ED

Ed Gresser is Vice President and Director for Trade and Global Markets at PPI.

Ed returns to PPI after working for the think tank from 2001-2011. He most recently served as the Assistant U.S. Trade Representative for Trade Policy and Economics at the Office of the United States Trade Representative (USTR). In this position, he led USTR’s economic research unit from 2015-2021, and chaired the 21-agency Trade Policy Staff Committee.

Ed began his career on Capitol Hill before serving USTR as Policy Advisor to USTR Charlene Barshefsky from 1998 to 2001. He then led PPI’s Trade and Global Markets Project from 2001 to 2011. After PPI, he co-founded and directed the independent think tank Progressive Economy until rejoining USTR in 2015. In 2013, the Washington International Trade Association presented him with its Lighthouse Award, awarded annually to an individual or group for significant contributions to trade policy.

Ed is the author of Freedom from Want: American Liberalism and the Global Economy (2007). He has published in a variety of journals and newspapers, and his research has been cited by leading academics and international organizations including the WTO, World Bank, and International Monetary Fund. He is a graduate of Stanford University and holds a Master’s Degree in International Affairs from Columbia Universities and a certificate from the Averell Harriman Institute for Advanced Study of the Soviet Union.

Read the full email and sign up for the Trade Fact of the Week