issue: Trade

Gresser in Politico: Trump’s Nemesis, the US Trade Deficit, Hit Record High in 2024

Trump has made reducing the trade deficit “to zero” a primary goal of his trade policy, White House trade counselor Peter Navarro said Tuesday at a POLITICO event where he blamed imports for millions of lost jobs, thousands of factory closings and a grim trail of divorces, alcoholism, drug addiction and death among America’s working class.

However, that’s a slanted view of imports, which lower costs for consumers and U.S. manufacturers, thereby supporting jobs in the United States, said Ed Gresser, vice president in charge of trade at the Progressive Policy Institute, a Democratic think tank. It also ignores the role that technology has played in manufacturing job losses, he said.

In addition, even though the goods trade deficit now is regularly above $1 trillion, it remains relatively small as a percentage of the U.S. economy, which has continued to grow over the years. In fact, the trade deficit is most likely to decline “when the economy goes really bad,” said Gresser, from the Progressive Policy Institute.

“The biggest trade deficit reductions we’ve had in the 21st century were during the financial crisis in 2009 and the Covid pandemic in 2020,” Gresser said. “That type of experience is quite effective at reducing trade deficits, but it always comes with many fewer jobs and depressed economies. It does not come with numerous openings of factories.”

Gresser, an economist and former U.S. trade official, said Trump’s first term provided a real-world example of why more tariffs won’t reduce the trade deficit.

That’s because the level of government spending plays a huge role in the macroeconomic factors that determine the size of the trade deficit. The Republican-led Congress cut far more in taxes during his first term than Trump raised in new tariff revenue, causing both the U.S. fiscal deficit and trade deficit to rise, Gresser said.

However, even if Republicans perfectly matched the multi-trillion-dollar cost of extending the 2017 tax cuts with trillions of dollars of new tariff revenue, that would not reduce the trade deficit, since the government’s fiscal deficit would remain the same, Gresser said.

“If you’re raising tariff rates and reducing income tax rates, the main thing you’re doing is shifting taxation from wealthy people to hourly wage workers and their families,” Gresser said. “That’s going to raise the cost of goods and have a big impact on reducing tax bills for the wealthiest people. Your impact on trade balance, if they offset exactly, will be nil.”

Canada, Mexico, and China are the U.S.’ three largest trading partners

FACT: Canada, Mexico, and China are the U.S.’ three largest trading partners

THE NUMBERS: Temperature tonight in Lewiston, Maine – -5°

* Accuweather forecast. Minus five degrees in Fahrenheit system; Celsius equivalent -20°.

WHAT THEY MEAN:

Following up on our statement on Mr. Trump’s attempt to raise tariffs on products from Canada, Mexico, and China last Saturday — a 10% tax on smartphones, laptops, and other Chinese-assembled products in place and 25% taxation of Canadian and Mexican-made stuff perhaps in a few weeks — here are PPI’s four principles for response to tariffs and economic isolationism:

- Defend the Constitution and oppose attempts to rule by decree;

- Connect tariff policy to growth, work, prices and family budgets, and living standards;

- Stand by America’s neighbors and allies;

- Offer a positive alternative.

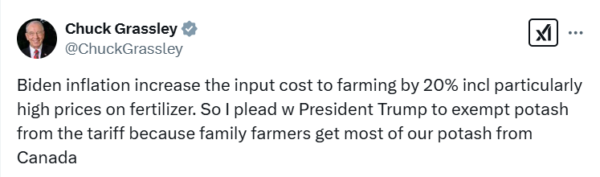

Regrettably, we’ll likely have a lot to say about these this year. Others, too. Here for example is Iowa Senator Charles Grassley on Monday, connecting tariffs to the daily farm economics:

“I plead w/ President Trump to exempt potash from the tariff because family farmers get most of their potash from Canada.”

Similar notes from other Republican Senators: Kevin Cramer (R-N.D.) worries about the loss of 80% of North Dakota’s export trade as, provoked beyond their normal good nature, Canadians publish retaliation lists; Susan Collins (R-Maine) thinks of Maine businesses and (noting this week’s Arctic-level Lewiston thermometer readings) fears a sudden spike in home heating bills:

“The Maine economy is integrated with Canada, our most important trading partner. Certain tariffs will impose a significant burden on many families, manufacturers, the forest products industry, small businesses, lobstermen, and agricultural producers. For example, 95 percent of the heating oil used by most Mainers to heat their homes comes from refineries in Canada.”

To put a number on this, Maine bought $2.73 billion worth of fuel oil, mostly for heating oil from Canada last year, so Mr. Trump’s midwinter 10% energy tariff would have hit the state’s 590,000 households with a new $270 million bill.

These tariff threats were only temporarily withdrawn Monday evening, though, and return in three weeks. So before they do, some stats on their potential impact for energy, food, consumer goods, and industrial supply costs in the United States; then a thought on the options open to the Senators and Reps. making these sorts of complaints.

Crude oil: Canada supplies about 60% of America’s crude oil imports, and Mexico another 10%. Even setting aside refined products like New England’s home heating oil, the two countries together provide about 30% of the crude oil American refineries use for gasoline, jet fuel, and locally refined heating oil. The value of crude alone last year came to $107 billion, meaning a 25% tariff at face value raises the refineries’ bills by about $27 billion, with the bill coming due later on for families at gas stations and in heating bills.

Toys: China ships about 80% of U.S. toys — $12 billion in 2023 — and Mexico another 5%, suggesting higher costs for birthday parties this spring and Christmas presents further ahead.

Phones and TV sets: China likewise supplies about 80% of the smartphones sold in the U.S. (with Vietnam and India as the other two suppliers). For TV sets, the Chinese share is a more modest 50%, and the Mexican share is 10%.

Groceries: Mexico is the U.S.’ top source of winter vegetables and fruit, supplying grocery stores with about $2.5 billion worth of fresh produce each month in wintertime. Last month, we noted that in February of 2024, this came to 188,640 tons of tomatoes, 128,330 tons of peppers, 106,460 tons of avocadoes, and 44,440 tons of lemons and limes. Here are some more February 2024 purchases: 44,000 tons of fresh strawberries and 26,000 tons of raspberries, 110,000 tons of jalapenos and other chili peppers, and 97,450 tons of cucumbers. One could go on.

Auto parts: Of the $139 billion worth of auto parts American factories and repair shops bought last year from abroad, $65 billion worth came from Mexico, $16 billion from Canada, and $12 billion from China. So expect your U.S.-made car to cost more and your repair bills to rise along with the gas prices.

The toy/phone/TV tariffs may or may not stay on, and the threats to impose tariffs by decree on purchases from Canada and Mexico come back in three weeks. What then are the Senators’ options? Their concern about rising costs for farmers and lobster boat captains, cold homes, threats to jobs, and stretched family budgets is actually linked very closely to the first principle of response — defend the Constitution and oppose attempts to rule by decree. The Constitution’s tariff clause is not at all blurry: “Congress shall have the Power to lay and collect Taxes, Duties, Imposts, and Excises.” So Republican Senators and Representatives have no need to plead for special carveouts and exemptions. They have all the power they need to keep potash and heating oil prices down, and to preserve Congress’ constitutional authority from Mr. Trump’s power grab, by voting. They just need to use it.

FURTHER READING

Trump administration “Fact Sheet” on tariffs:

… vs. Constitution, see Article 1, Section 8, assigning Congress power over “Taxes, Duties, Imposts, and Excises”.

A Congressional perspective:

A statement from the New Democrat Coalition.

And a preventive for this sort of stunt:

Reps. Suzanne DelBene (D-Wash.) and Don Beyer (D-Va.) have a bill to ban the use of the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (designed for response to the outbreaks of wars, pandemics, and so on) for creating tariff systems.

ABOUT ED

Ed Gresser is Vice President and Director for Trade and Global Markets at PPI.

Ed returns to PPI after working for the think tank from 2001-2011. He most recently served as the Assistant U.S. Trade Representative for Trade Policy and Economics at the Office of the United States Trade Representative (USTR). In this position, he led USTR’s economic research unit from 2015-2021, and chaired the 21-agency Trade Policy Staff Committee.

Ed began his career on Capitol Hill before serving USTR as Policy Advisor to USTR Charlene Barshefsky from 1998 to 2001. He then led PPI’s Trade and Global Markets Project from 2001 to 2011. After PPI, he co-founded and directed the independent think tank ProgressiveEconomy until rejoining USTR in 2015. In 2013, the Washington International Trade Association presented him with its Lighthouse Award, awarded annually to an individual or group for significant contributions to trade policy.

Ed is the author of Freedom from Want: American Liberalism and the Global Economy (2007). He has published in a variety of journals and newspapers, and his research has been cited by leading academics and international organizations including the WTO, World Bank, and International Monetary Fund. He is a graduate of Stanford University and holds a Master’s Degree in International Affairs from Columbia Universities and a certificate from the Averell Harriman Institute for Advanced Study of the Soviet Union.

Read the full email and sign up for the Trade Fact of the Week.

PPI Statement on President Trump’s Reckless Tariffs

WASHINGTON — Today, Ed Gresser, Vice President and Director for Trade and Global Markets at the Progressive Policy Institute (PPI), issued the following statement in response to President Trump imposing a 25% tariff on goods from Mexico and Canada, and a 10% tariff on Chinese goods:

“Mr. Trump’s use of a bad-faith ‘state of emergency’ to launch a bizarre and unprovoked economic attack on America’s closest neighbors and largest export markets is bad economics and bad national security. If sustained, it will mean higher prices for American families on everything from heating oil to fresh vegetables and auto repair bills, increased production costs for American businesses and lost export sales for farmers and manufacturers, diminished American influence in the world, and likely new — in fact, unprecedented — North American security problems for all of Mr. Trump’s successors. It is also bad tax policy: while unable to raise the revenue a modern government needs for defense, retirement, and health programs, tariffs very efficiently shift tax burdens from wealthy households to hourly-wage families, and from services businesses like real estate and financial services to manufacturers, retailers, restaurants, construction firms, and agriculture.

“As damaging as all this will be, the systemic implications of this step for American governance are even worse. One-man creation of a new tariff system is an open invitation to future corruption, as — aware they can create new tariff systems by themselves — all future presidents will face temptation to use tariffs to punish critics and rivals, and to reward supporters and cronies. Still more fundamentally, it usurps Congress’ Constitutional power over ‘Taxes, Duties, Imposts and Excises,’ and substitutes rule by personal decree for legitimate legislation. As such, today’s attempted action is a breach of the separation of powers and a threat to the Constitution. House Speaker Mike Johnson, Ways and Means Committee Chairman Jason Smith, and their Senate counterparts Majority Leader John Thune and Finance Committee Chairman Mike Crapo, must oppose this power grab and, per the Congressional oath of office, support and defend the Constitution.”

PPI recently outlined four key principles for responding to tariff-driven economic isolationism. Additionally, PPI has warned of the economic risks posed by Trump’s tariff policies in a recent report and detailed these concerns in testimony before Congress and in PPI’s own coverage. For further context on the Constitution over tariffs and taxation and how the legislative, not executive branch, has the authority, see the full text of the U.S. Constitution.

Founded in 1989, PPI is a catalyst for policy innovation and political reform based in Washington, D.C. Its mission is to create radically pragmatic ideas for moving America beyond ideological and partisan deadlock. Find an expert and learn more about PPI by visiting progressivepolicy.org. Follow us @PPI.

###

Media Contact: Ian O’Keefe – iokeefe@ppionline.org

Gresser in Axios: What’s at Stake if Canada and Mexico Tariffs Happen

Mexico is the country’s largest source of winter fruit and vegetable imports. Last February, U.S. grocery stores imported $2.25 billion worth of fresh produce from Mexico, per federal data analyzed by the Progressive Policy Institute.

- That included 128,330 tons of peppers, 106,460 tons of avocados, and 44,440 tons of lemons and limes.

- “Grocery stores rely very heavily on Mexico for about half (their) fresh produce imports,” says Ed Gresser, vice president at the institute.

- “If you wanted to shift that to U.S. production it would be very hard. You’d have to go to a lot of greenhouses and it would be very expensive,” adds Gresser, a former assistant U.S. trade representative for policy and economics.

U.S. drug overdose deaths down 21.7% from 2023 to 2024.

FACT: U.S. drug overdose deaths down 21.7% from 2023 to 2024.

THE NUMBERS: CDC estimates of U.S. deaths by drug overdose –

| 12 months ending August 2024: | 89,740 |

| 12 months ending August 2023: | 111,464 |

| Full-year 2023 | 110,037 |

| Full-year 2022 | 112,582 |

WHAT THEY MEAN:

From the Drug Enforcement Administration last Saturday, a report from Tucson:

“The United States Attorney’s Office for the District of Arizona announced today that extensive bilateral cooperation between the United States and Mexico resulted in Mexico’s Attorney General’s Office, Fiscalía General de la República (FGR), conducting a significant enforcement operation last week in Nogales, Sonora, to dismantle a prolific transnational drug trafficking organization operating along the U.S. Mexico border. The operation resulted in the arrest of two individuals in Mexico including the leader of the organization, Heriberto Jacobo Perez, and another member of the organization, Jesus Bernardo Rodriguez. Mexican authorities also seized four vehicles, two buildings, two firearms currency, a large number of fentanyl pills, and other controlled substances.”

Some background and then a wide-view look:

Deaths to drug overdoses in the United States rose fast and steadily for two decades. The Centers for Disease Control estimated 17,400 deaths in 2000, 41,500 in 2012, 43,697 in 2016, 92,500 in 2020, and peaks above 110,000 in 2022 and 2023. For context, the 112,582 deaths in 2022 is 50% above that year’s combined 42,514 deaths to car accidents (itself the highest traffic fatality figure in a decade) and 24,849 homicides. Synthetic opioids, in particular fentanyl, are the main cause, accounting for 87,155 or 78% of all American drug overdose deaths in 2023.

CDC’s most recent numbers show a startling change: drug overdose deaths turned down in mid-2023 and have been falling ever since. The CDC’s latest estimates cover August 2024. These report 89,740 overdose deaths over the 12 months since September 2023: a drop of 22,000, or 21.7%, from the 111,464 estimated from September 2022 to August 2023. Some states show even steeper drops, with North Carolina deaths down 51%, Virginia 32%, New Jersey and Ohio 30%, and Pennsylvania 27%. The decline is almost entirely in “synthetic opioids” such as fentanyl, for which the CDC estimates 79,815 deaths between September 2022 and August 2023, and 57,997 from September 2023 to August 2024. Extrapolating carefully from this 12-month number to individual months, and assuming no sharp change last autumn, the full-year 2024 toll would be somewhere between 70,000 and 80,000. This would be the largest one-year drop in deaths on record.

What explains this? Probably not any single factor, but complementary developments in three broad areas:

Source reduction abroad and at home: Last week’s Tucson event illustrates the value of U.S.-Mexican law enforcement cooperation. The Drug Enforcement Administration reports continuous pressure on the two large narcotics “cartels” responsible for most fentanyl trafficking, and notes that the 55.5 million fentanyl pills seized in 2024 test are somewhat less powerful — half contain potentially lethal doses, as opposed to 70% in earlier years — and so somewhat less likely to kill their users. (Administrator Milgram: “[F]ive out of ten pills being lethal is awful and we should not accept that. But it is significant progress in our fight to save lives, because it means that for every ten pills on the street, two fewer are deadly today.”) Nor are foreign countries the only sources: the fentanyl epidemic began with domestic prescriptions, and legal U.S.-based uses of opioids are declining, with prescriptions down from 154 million in 2019 to 125 million in 2023.

Treatment: Over the past four years, with harm-reduction support flowing from Congress to clinics and hospitals, testing and emergency treatment have become easier to find. The CDC, for example, notes that doses of Naloxone, chemically an “opioid antagonist” used to restore normal breathing during fentanyl overdoses via injection or nasal spray, doubled from 1.00 million in 2020 to 2.13 million in 2023.

Education: With schools, police offices, health services, and state governments informing the public about the particularly severe risk fentanyl carries — two milligrams in a single pill is a lethal dose — users are likely more aware of the danger and may be turning away from opioids.

In this larger view, DEA’s Saturday report from Tucson is another bit of encouraging news. Echoing Administrator Milgram, a year in which 70,000 or 80,000 people die of drug overdoses is a bad year. But it’s better than we’ve had in a while, with a drop large enough, and sustained long enough, to suggest that we might have turned a corner.

FURTHER READING

The CDC’s overdose data and mortality estimates through August 2024.

And via CDC’s data, deaths by drug overdose from 2000 to 2023, with a tentative estimate for 2024 based on the data available through August:

| 2024 | 75,000? |

| 2023 | 110,037 |

| 2022 | 112,582 |

| 2021 | 107,500 |

| 2020 | 92,500 |

| 2019 | 71,100 |

| 2016 | 63,600 |

| 2012 | 41,500 |

| 2000 | 17,400 |

Perspectives:

From Congress, Rep. Brittany Pettersen (D-CO) on a painful family experience and current work to raise community treatment and recovery capacity in last year’s “SUPPORT” Act.

From the Drug Enforcement Administration, a report from Tucson.

… background on fentanyl and its effects.

.. and DEA’s status report to the National Family Summit on Fentanyl last November from Administrator Anne Milgram, covering indictments, diplomatic and law-enforcement engagements with China and Mexico.

From the National Institutes of Health, an introduction to Naloxone.

And back to the CDC for data on Naloxone doses from 2019 to 2023 nationally and by state, along with domestic opioid prescriptions and Buprenorphine delivery.

And some international context:

UN’s Office on Drugs and Crime’s World Drug Report 2024 reviews drug production, transport, health, and other policy matters around the world. They estimate 60 million opioid and opiate users worldwide, including 9 million in North America, in a global drug-user population of 292 million.

ABOUT ED

Ed Gresser is Vice President and Director for Trade and Global Markets at PPI.

Ed returns to PPI after working for the think tank from 2001-2011. He most recently served as the Assistant U.S. Trade Representative for Trade Policy and Economics at the Office of the United States Trade Representative (USTR). In this position, he led USTR’s economic research unit from 2015-2021, and chaired the 21-agency Trade Policy Staff Committee.

Ed began his career on Capitol Hill before serving USTR as Policy Advisor to USTR Charlene Barshefsky from 1998 to 2001. He then led PPI’s Trade and Global Markets Project from 2001 to 2011. After PPI, he co-founded and directed the independent think tank ProgressiveEconomy until rejoining USTR in 2015. In 2013, the Washington International Trade Association presented him with its Lighthouse Award, awarded annually to an individual or group for significant contributions to trade policy.

Ed is the author of Freedom from Want: American Liberalism and the Global Economy (2007). He has published in a variety of journals and newspapers, and his research has been cited by leading academics and international organizations including the WTO, World Bank, and International Monetary Fund. He is a graduate of Stanford University and holds a Master’s Degree in International Affairs from Columbia Universities and a certificate from the Averell Harriman Institute for Advanced Study of the Soviet Union.

Read the full email and sign up for the Trade Fact of the Week.

Gresser in The Washington Post: Trump’s Second Trade War Will Be Different From His First

Trump may have backed off those particular trade threats, buthe has mused about new import taxes in virtually every public appearance since his inauguration. And the studies he ordered hint at creative uses of presidential powers, including a potential doubling of the tax rate for some foreign individuals and companies.

“I think it’s significantly different right now. The threats are much more expansive. The sense of legal constraints seems much less,” said Ed Gresser, who led the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative’s economic research unit during Trump’s first term. “It suggests he feels as president he has the right to create a whole new tariff system all by himself.”

Trump appears all but certain to act earlier in his second term than he did in his first, when he waited a full year before slapping tariffs on foreign-made washing machines and solar panels. He has threatened to impose tariffs on China, Canada and Mexico on Feb. 1 while suggesting that Europe, Russia, Brazil, India and several other countries could also see their goods taxed.

Read more in The Washington Post.

The world economy is growing and ‘normalizing’ in 2025. Or else not.

FACT: The world economy is growing and ‘normalizing’ in 2025. Or else not.

THE NUMBERS: World economy at the end of 2024 –

| 2020 | 2024 | |

| Population | 7.8 billion | 8.2 billion |

| Absolute poverty rate | 9.7% | 9.0% |

| GDP (real 2024 dollars) | $93.8 trillion | $110.7 trillion |

| (U.S.) | ($25.4 trillion) | ($29.2 trillion) |

| Trade flows | $22.7 trillion* | ~$33 trillion |

| Operating satellites | ~2,500 | ~9,500 |

| Live submarine cables | 400 | 600 |

| Container-ship capacity | 25.8 million TEU | 32 million TEU |

| Widebody freighter air fleet | 2,010 | 2,340 |

* Anomalously low due to COVID-19 economic closures. The 2019 total was $25.0 trillion.

WHAT THEY MEAN:

Peering into the near future in its “World Economic Outlook” update last Thursday, the International Monetary Fund sees a “normalizing” 2025 for the world economy. The Fund’s mighty banks of computers, integrating figures on savings rates, energy costs, retirements, fiscal balances, investment levels, debt loads, and the like, arrive at projections of worldwide growth of 3.3%, fading inflation, and interest rates possibly trending down. Economic Counsellor Pierre-Olivier Gourinchas summarizes the “data-driven” outlook:

“We project global growth will remain steady at 3.3% this year [as against 3.2% in 2024 and 2023], broadly aligned with potential growth … inflation is declining, to 4.2% this year and 3.5% next year, which will allow further normalization of monetary policy. This will help draw to a close the global disruptions of recent years, including the pandemic and the Russian invasion of Ukraine.”

Dr. Gourinchas goes on to note some variability of growth among big economies, noting that the U.S. and China are the relatively strong-growth big economies, though both with some asterisks. China’s boom era is past: its 4.5% growth projection is now similar to the 4.2% the IMF sees for other “emerging economies” and the 4.1% for low-income countries, and well below India’s 6.5%. Benefiting from relatively high productivity growth, meanwhile, American living standards are “pulling away from those of other advanced economies”; but the U.S. has higher inflation risk than its peers for other reasons: a likely rising budget deficit, plus immigration and tariff plans seen as stagflationary.* Continental Europe, on the other hand, is slower than it should be, with 1.0% growth — a bit below the 1.6% for the U.K. and the 1.1% for Japan.

The projections suggest general calm, a prospering if not booming world, and the sort of problems that usually come up in normal times. Data cited above from other venues — trade flows, rising air and maritime logistical capacity, rapid satellites and fiber-optic cable deployment, a slowly falling rate of deep poverty — all seem to say this needn’t stop any time soon. So here’s J.M. Keynes in The Economic Consequences of the Peace (1919) to remind us of how quickly and badly things can go wrong when — despite equations, data, and rational predictions drawn from them — governments and publics make poor choices:

“What an extraordinary episode in the economic progress of man that age was, which came to an end in August, 1914! … [For] the middle and upper classes, life offered, at a low cost and with the least trouble, conveniences, comforts, and amenities beyond the compass of the richest and most powerful monarchs of other ages. The inhabitant of London could order by telephone, sipping his morning tea in bed, the various products of the whole earth, in such quantity as he might see fit, and reasonably expect their early delivery upon his doorstep; he could at the same moment and by the same means adventure his wealth in the natural resources and new enterprises of any quarter of the world, and share, without exertion or even trouble, in their prospective fruits and advantages; or he could decide to couple the security of his fortunes with the good faith of the townspeople of any substantial municipality in any continent that fancy or information might recommend.”

“[H]e regarded this state of affairs as normal, certain, and permanent, except in the direction of further improvement, and any deviation from it as aberrant, scandalous, and avoidable. The projects and politics of militarism and imperialism, of racial and cultural rivalries, of monopolies, restrictions, and exclusion, which were to play the serpent to this paradise, were little more than the amusements of his daily newspaper, and appeared to exercise almost no influence at all on the ordinary course of social and economic life.”

Back to the IMF for the last word: Dr. G. is more alert to this sort of risk than was Keynes’ wealthy and oblivious Londoner just before the First World War. His closing comment steps back from data-driven optimism to anxiety about policy and human choices:

“Finally, additional efforts should be made to strengthen and improve our multilateral institutions to help unlock a richer, more resilient, and sustainable global economy. Unilateral policies that distort competition—such as tariffs, nontariff barriers, or subsidies—rarely improve domestic prospects durably. They are unlikely to ameliorate external imbalances and may instead hurt trading partners, spur retaliation, and leave every country worse off.”

* Direct quote on mass deportations and tariff increases: “Will play out like negative supply shocks, reducing output and adding to inflation.”

FURTHER READING

The IMF’s Gourinchas on the year ahead.

… and the full “World Economic Outlook” update.

Keynes’ Economic Consequences of the Peace (1919).

And the Biden administration’s last word on the economy.

ABOUT ED

Ed Gresser is Vice President and Director for Trade and Global Markets at PPI.

Ed returns to PPI after working for the think tank from 2001-2011. He most recently served as the Assistant U.S. Trade Representative for Trade Policy and Economics at the Office of the United States Trade Representative (USTR). In this position, he led USTR’s economic research unit from 2015-2021, and chaired the 21-agency Trade Policy Staff Committee.

Ed began his career on Capitol Hill before serving USTR as Policy Advisor to USTR Charlene Barshefsky from 1998 to 2001. He then led PPI’s Trade and Global Markets Project from 2001 to 2011. After PPI, he co-founded and directed the independent think tank ProgressiveEconomy until rejoining USTR in 2015. In 2013, the Washington International Trade Association presented him with its Lighthouse Award, awarded annually to an individual or group for significant contributions to trade policy.

Ed is the author of Freedom from Want: American Liberalism and the Global Economy (2007). He has published in a variety of journals and newspapers, and his research has been cited by leading academics and international organizations including the WTO, World Bank, and International Monetary Fund. He is a graduate of Stanford University and holds a Master’s Degree in International Affairs from Columbia Universities and a certificate from the Averell Harriman Institute for Advanced Study of the Soviet Union.

Read the full email and sign up for the Trade Fact of the Week.

The last big U.S. tariff increase: Herbert Hoover’s, in June 1930

FACT: The last big U.S. tariff increase: Herbert Hoover’s, in June 1930.

THE NUMBERS: U.S. tariff rates* –

| 1929 | 13.5% |

| 1933 | 19.8% (modern-era peak) |

| 1940 | 12.5% |

| 1960 | 7.1% |

| 1980 | 3.1% |

| 2000 | 1.6% |

| 2010 | 1.4% |

| 2015 | 1.5% |

| 2020 | 2.8% |

| 2023 | 2.4% |

| 2025 | ? |

*Trade-weighted” averages, dividing tariff revenue by goods import value. U.S. International Trade Commission, at https://www.usitc.gov/documents/dataweb/ave_table_1891_2023.pdf.

WHAT THEY MEAN:

The incoming administration has — it says — a plan for the first big U.S. tariff increase since Herbert Hoover’s in 1930. But as PPI’s Ed Gresser observes in Tariffs and Economic Isolationism: Four Principles for a Response today (borrowing some post-Hoover lyrics) even at this late date, a week before the inauguration, whatever this plan might be ain’t exactly clear. With a detailed response still premature, his piece offers four principles as a foundation:

1. Defend the Constitution.

2. Connect tariffs and trade policy to American family living standards, growth, and work.

3. Stand by America’s neighbors and allies.

4. Offer a positive alternative.

Some background first, then a bit more on each:

Trump campaign documents, and more recent transition statements, float at least five tariff plans, mostly incompatible: (i) a higher overall tariff, of 10% or possibly 20%, probably stacked on top of the current 2.4%, imposed by decree after a declaration of “emergency”; (ii) threats to impose tariffs on particular countries over unrelated policy issues, also presumably by decree; (iii) a new “Rube Goldberg” tariff schedule in which every U.S. HTS-8 line is equal to or higher than the precisely comparable line in every other customs territory; (iv) a Congressional bill like Hoover’s; (v) tariffs on products administration officials decide are especially sensitive. Since it isn’t clear which (if any) of these is the “real” plan, for now, critics need no detailed analysis or response. But we can start with two basic observations and principles applicable to all:

Tariffs and their uses: Tariffs have some valid uses. They can provide temporary protection for industries trying to rebuild competitiveness, for example, or help to economically isolate an aggressor state. But they always raise costs for families and goods-using businesses, incite foreign governments to retaliate against American farm and manufacturing exporters, and often reward good lobbyists more than good products. As Laura Duffy points out in her PPI report last fall, tariffs are also inequitable and regressive as both consumer and business taxes. So they’re generally poor policy, and governments should reserve them for the unusual cases where they’re really necessary.

The Biden record and its lessons: Critics should not be bound by “Bidenomics,” and, in fact, should make some clear breaks with it. President Biden’s 2021-2024 program had many good results — steady growth, low unemployment, a strengthened semiconductor industry, and progress on decarbonization. But it ended as a political liability, and his approach to tariffs contributed to this. Despite several useful trade innovations (e.g., the Commerce Department’s export promotion ideas and the Treasury’s “friendshoring” concept), the administration abandoned the market-opening, liberalizing values of Roosevelt-to-Obama Democrats and tried instead to blur differences with Trumpism by leaving Mr. Trump’s 2018/19 tariffs mostly untouched. This cost the Biden team a chance to bring down prices by cutting tariffs; left it unable to assign the first Trump term its appropriate share of blame for the post-Covid inflation burst; and (as we warned in mid-2023) by 2024, lacked the positive growth-and-living-standards agenda that should have complemented Vice President Harris’ forceful critique of Trump’s tariff hikes.

Now back to the four principles:

1. Defend the Constitution. The Constitution gives Congress full authority to set “Taxes, Duties, Imposts, and Excises.” For good reason: if a president can create his or her own tariff system by decree, not only do impulsive and ill-considered decisions become more likely, but all future presidents would face standing temptation to use tariffs in corrupt ways to reward supporters and cronies, or punish critics and rivals. Attempts to impose tariffs by perverting existing laws meant for wholly different purposes – emergency actions meant for a sudden crisis, trade negotiating leverage, etc. – and rule by decree rather than legitimate (even if ill-judged) legislation breach the separation of powers and harm the Constitution, and should be opposed on principle.

2. Connect tariffs to American family living standards, growth, and work. Tariffs are usually poor policy. As consumer taxation, they hit single moms much harder than stockbrokers, and average families much more than wealthy households. As business taxes, they raise costs for goods-purchasers — manufacturing, retail, restaurants, farms, building contractors — more than for investment- and services-heavy industries like real estate and finance. And as trade policy, they invite retaliation against America’s $3 trillion export sector — top in the world for agriculture, services, and energy, and second in manufacturing — whose factories and farms deserve better than to have an administration turn them into trade-war cannon fodder.

3. Stand by America’s allies and neighbors. America’s alliances with democracies and close relations with neighbors are strategic assets built over decades. Mr. Trump’s use of his free time in these past months to pick fights, including through tariff threats, with allies and neighbors from Canada and Denmark to Mexico and Panama has thus been an especially corrosive and disturbing part of this transition period. Economics apart, these countries have stood with the U.S. when it counted a lot — not long ago, and at a considerable cost. Remember, for example, that Denmark lost 43 soldiers in Iraq and Afghanistan and Canada 158. Neither deserves repayment with bullying and economic threats. The right policy is to deepen and strengthen these relationships, and to oppose attempts to erode and weaken them through tariff threats.

4. Offer a positive alternative. Though the incoming administration’s plans are uncertain, and there’s no need yet for a detailed alternative, it’s useful even now to consider the shape it might take. The essay suggests three lines of policy:

* International engagement: Modernized trade agreements to deepen and strengthen economic relationships with friends, neighbors, and allies. These can include U.S.-Europe agreements with the United Kingdom as an immediate choice; a return to the 15-country Trans-Pacific Partnership, now functioning very well as the “CPTPP” for Japan, Australia, Canada, and other allies, including the U.K.; and using the 2026 “USMCA” “review” to broaden that agreement to Caribbean, Central, and South American countries.

* Domestic reform to cut costs: Cut the cost of living for hourly-wage families by scrapping especially regressive, discriminatory, and sexist tariffs, with the Pink Tariffs Study Act introduced by Representatives Lizzie Fletcher and Brittany Pettersen as the starting point.

* Constitutionally appropriate policymaking: Here the Prevent Tariff Abuse Act introduced in December by Reps. Suzanne DelBene and Don Beyer, which excludes tariffs from actions presidents can take under the International Emergency Economic Powers Act, sets the example.

Here’s the piece.

FURTHER READING

Gresser on Tariffs and Economic Isolationism: Four Principles for a Response.

More from PPI on trade policy, tariffs, and America in the world economy:

Gresser’s December 2024 testimony to the Joint Economic Committee on the implications of a higher national tariff.

…and from early 2023, his warning (in response to a disquieting speech by the National Security Advisor) about the Biden administration’s poor tariff-and-trade positioning for a rematch with Trumpism.

Laura Duffy’s It’s Not 1789 Anymore explains why, though tariffs were the best of a poor set of options for the first Congress in 1789 and remain important for revenue in very low-income and troubled countries today, they’re a bad form of taxation — high rates and narrow base mean they can’t raise enough revenue, also opaque, regressive, and inequitable.

Yuka Hayashi’s The U.S. Wants Manufacturing to Drive Growth. Foreign Friends Can Help on pooling economic strengths with allies.

And just for the record …

What happened the last time the U.S. government tried a general tariff increase? Herbert Hoover’s “Tariff Act of 1930”, colloquially known as “Smoot-Hawley” for its Congressional authors Sen. Reed Smoot and Rep. Willis Hawley, passed on a rainy June day in 1930. Metaphorically, the rain continued for years:

| U.S. GDP, 1929*: | $1.191 trillion |

| U.S. GDP, 1930: | $1.090 trillion |

| Real GDP growth, 1930: | -8.5% |

| Real GDP growth, 1931: | -6.4% |

| Real GDP growth, 1932: | -12.9% |

| U.S. GDP, 1933: | $0.877 trillion |

| Unemployment, 1933: | 24.9% |

* Bureau of Economic Analysis, GDP in ‘real’ 2017 dollars; U.S. 2024 GDP by this measure is now $23.4 trillion.

Modern economic historians view this tariff increase not as a main cause of the Depression – conventionally dated as starting eight months earlier, with the stock market crash of late October 1929 — but as a bad idea that made it deeper and longer. (Depending on one’s preference, “main causes” include financial-system collapse and serial bank failures without deposit insurance, absence of a “lender of last resort” for distressed but viable sectors, failure of government to respond with fiscal stimulus as household spending collapsed, Federal Reserve interest policies, the “gold standard” as an international factor, and so on.) The tariff increase created no jobs or investment, and the foreign retaliations it brought helped wreck the export sector and seal potential routes to relief. Four looks at the experience:

Charles Kindleberger’s analytical The World in Depression, 1929-1939

J.K. Galbraith’s The Great Crash, 1929 on the view from Wall Street in the months before Smoot-Hawley.

Franklin D. Roosevelt’s 1936 Address to the Inter-American Conference on the Maintenance of Peace in Buenos Aires, looks back six year later on rising trade barriers, the collapse of trade, and their effects on peace and security.

And Douglas Irwin’s Peddling Protectionism has a contemporary take at the Hoover administration, Congress, the Tariff Act of 1930, and its consequences.

ABOUT ED

Ed Gresser is Vice President and Director for Trade and Global Markets at PPI.

Ed returns to PPI after working for the think tank from 2001-2011. He most recently served as the Assistant U.S. Trade Representative for Trade Policy and Economics at the Office of the United States Trade Representative (USTR). In this position, he led USTR’s economic research unit from 2015-2021, and chaired the 21-agency Trade Policy Staff Committee.

Ed began his career on Capitol Hill before serving USTR as Policy Advisor to USTR Charlene Barshefsky from 1998 to 2001. He then led PPI’s Trade and Global Markets Project from 2001 to 2011. After PPI, he co-founded and directed the independent think tank ProgressiveEconomy until rejoining USTR in 2015. In 2013, the Washington International Trade Association presented him with its Lighthouse Award, awarded annually to an individual or group for significant contributions to trade policy.

Ed is the author of Freedom from Want: American Liberalism and the Global Economy (2007). He has published in a variety of journals and newspapers, and his research has been cited by leading academics and international organizations including the WTO, World Bank, and International Monetary Fund. He is a graduate of Stanford University and holds a Master’s Degree in International Affairs from Columbia Universities and a certificate from the Averell Harriman Institute for Advanced Study of the Soviet Union.

Read the full email and sign up for the Trade Fact of the Week.

New PPI Analysis Introduces Principles for Response to Trump’s Reckless Tariff Agenda

WASHINGTON — President-elect Donald Trump has threatened to impose tariffs as high as 20% on everything Americans buy from abroad, from crude oil and fresh vegetables to auto parts, toys, and Valentine’s Day roses. This would be the highest U.S. tariff rate since the 1930s, when the Hoover administration’s tariff increase — commonly termed “Smoot-Hawley” for its Congressional authors — deepened and lengthened the Great Depression.

As Mr. Trump prepares to be sworn in next Monday, the Progressive Policy Institute (PPI) today released a new analysis, “Tariffs and Economic Isolationism: Four Principles for a Response,” by Ed Gresser, Vice President and Director for Trade and Global Markets. Gresser argues that in response to Trump’s proposed tariffs, Democrats need to create an alternative that can deliver a lower cost of living for families, support agricultural and industrial exporters, and strengthen America’s position in a more dangerous world.

“Tariffs always raise costs and, in general, tend to lower living standards and erode industrial competitiveness,” said Gresser. “Broad tariff increases, trade wars, and higher prices are the wrong approach, and imposing them by decree from the Executive Branch would pose systemic risk to the Constitution.”

In the analysis, Gresser discusses four principles that together address the Constitutional, economic, strategic, and political issues the various Trump tariff proposals raise:

- Defend the Constitution and oppose attempts to rule by decree.

- Connect tariff policy, both as taxation and trade policy, to growth, work, prices and family budgets, and living standards.

- Stand by America’s neighbors and allies.

- Offer a positive alternative.

“In developing their response, Democrats need to make some clear breaks with the ‘Bidenomics’ formula,” said Gresser. “A trade agenda that avoids tariffs concedes far too much ground to isolationism, and misses opportunities to raise living standards and promote growth.”

Read the full analysis here.

The Progressive Policy Institute (PPI) is a catalyst for policy innovation and political reform based in Washington, D.C. Its mission is to create radically pragmatic ideas for moving America beyond ideological and partisan deadlock. Learn more about PPI by visiting progressivepolicy.org. Find an expert at PPI and follow us on Twitter.

###

Media Contact: Ian O’Keefe – iokeefe@ppionline.org

Tariffs and Economic Isolationism: Four Principles for a Response

The incoming Trump administration promises a very large increase in tariffs, perhaps to levels last seen during the mid-1930s in the Depression. As national policy, this would abandon the liberalizing program developed during the New Deal and extended under presidents of both parties all the way through the Obama administration. In its place would come something like the high-tariff worlds of Harding/Hoover isolationism in the 1920s, or (in Mr. Trump’s apparently preferred formulation) the even more remote Gilded Age of the 1880s and 1890s.

Just a week before the inauguration, in the real world of 2025, what will actually happen — to borrow from lyrics from a slightly later era — still ain’t exactly clear. Mr. Trump has proposed at least five different policies, mostly incompatible. One is an overall 10% or 20% tariff — the most Hoover-like option, with tariffs as much as ten times their current rate. Another is the imposition of tariffs on particular countries as tools for particular issues such as migration, and a third is stopping trade with China, Canada, and Mexico in particular. Last year’s Republican platform added a “Rube Goldberg”-style scheme in which each U.S. tariff line is equal to or higher than every analogous tariff line in every other country, and the tariff schedule balloons out to millions of lines; another option is traditional, Hoover-era tariff legislation. The most recent, via press trial balloons, is tariffs on products administration officials decide are especially sensitive.

Tariffs are occasionally necessary, of course. Governments can use them appropriately to give industries struggling with import surges or subsidized competition space to recover (as the Biden administration did last year with respect to Chinese-produced electric vehicles), or to isolate aggressor governments as with the punitive tariffs imposed on Russia in 2022. But they always raise costs — a strange choice for Mr. Trump to make, after the advantages his campaign drew from the inflation burst of 2021-2023 — and, in general, tend to lower living standards and erode industrial competitiveness. Depending on the way the incoming administration tries to impose them, they can also harm the separation of powers and the Constitution. And looking ahead, the Biden administration’s experience demonstrates the error of trying to answer by blurring differences or proposing “lite” versions of the same thing.

This doesn’t mean critics need a very detailed response now. That isn’t necessary until the administration program becomes clear. But they do need to lay the intellectual foundation for it soon. Here, then, are four principles, meant to bridge the Constitutional, economic, strategic, and political issues the various Trump proposals raise:

- Defend the Constitution and oppose attempts to rule by decrees.

- Connect tariff policy, both as taxation and trade policy, to growth, work, prices and family budgets, and living standards.

- Stand by America’s neighbors and allies.

- Offer a positive alternative.

I. MOVING BEYOND BIDENOMICS

In applying these principles, there’s no need for Democrats — or liberals in general, or others concerned about living standards, competitiveness, and America’s place in the world — to feel bound by Bidenomics. To the contrary, a new agenda needs some clear breaks with it.

President Biden’s program had some very positive results: low unemployment, steady growth, and faster decarbonization. Its “industrial strategy” programs, if expensive, do seem to have strengthened the semiconductor industry and might still prove durable ways to reduce emissions in automobiles and power plants. The Biden team also leaves some useful trade policy starting points: Commerce Secretary Raimondo’s innovative export promotion programs, Secretary Yellen’s Treasury concept of “friendshoring” as a way to ensure diverse sourcing and pool allied strengths in a more dangerous world, and Vice President Harris’s campaign summary of a broad tariff increase as fundamentally a tax increase on working families all make sense.

But Bidenomics also had failures and missed opportunities, and ended as a political liability. The White House badly oversold its “industrial strategy” as something that could create a much larger manufacturing sector, as opposed to the very important but less cosmic semiconductor and emissions-reduction plans. (Manufacturing, at 10.9% of GDP before Mr. Trump’s initial round of tariffs in 2018/19, fell to 10.3% by 2021. Its share now, industrial strategy or not, is 10.0%.) In trade policy as in some other areas, Bidenomics missed an opportunity to cut prices for families — obviously, the working-class public’s single largest concern last year — and make sure the first Trump administration bore its appropriate share of blame for inflation, by leaving the 2018/19 tariffs largely untouched and declaring the permanent tariff system untouchable. It stranded the U.S.’ $3 trillion export sector by giving up on lowering foreign trade barriers and promoting digital trade. Most important, as we warned nearly two years ago, its concession of tariff issues to Trump without a fight in 2021-2023 proved a grave political weakness in 2024, leaving Vice President Harris’ valiant campaign without a positive alternative to Trump’s tariff increases.

II. FOUR PRINCIPLES

The coming years require something else. What might it be? Trumpism will be better defined within a few months. Within a few years, any of its various proposals will likely create new problems (or recreate old ones) that require solutions we cannot now define. So, for now, a detailed response would be premature. But as a point of departure, here are four principles meant as a foundation for critiques of Trumpism and the development of alternatives:

1. Defend the Constitution. First, prevent breaches of the separation of powers, and insist that Congress consider any change in tariff policy in a Constitutionally appropriate way. The Constitution’s Article I, Section 8, gives Congress unambiguous authority over “Taxes, Duties, Imposts, and Excises,” and for good reason. No single individual, president or not, should have the power to create his or her own tax system out of nothing. That, at minimum, risks impulsive and ill-considered decisions. Even more seriously, it creates a standing temptation for all future presidents to use tariffs to reward personal friends and supporters, and likewise to punish critics, business rivals, and disaffected states.

As a legal matter, Congress has passed a number of laws “delegating” tariff policymaking to presidents in certain situations. Some seem Constitutionally sensible and convenient. Others, such as the International Emergency Economic Powers Act and sections 301 and 232 of U.S. trade law, give presidents too much unchecked power. But even in these cases, no law is meant to allow a president to create his own tariff system. Whether or not courts find such a step “unconstitutional,” given precedent from case law and Congressional drafting errors, as an obvious breach of an unambiguous Congressional power, it would certainly be “anti-Constitutional.” Congress should oppose the perversion of any current law for this purpose, insist that no general tariff increase ever occur absent a formal vote, and reject any attempt to impose tariffs by decree.

2. Connect trade and tariff policies to American living standards, work, and growth. Second, define tariff policy correctly as tax and trade policy, and analyze its effects on the basis of its impact on working family living standards, business competitiveness, and growth.

As Laura Duffy explained in her PPI paper last fall, tariffs are a poor form of taxation, distinguished from broader income or consumption taxes for narrow base and high rates, and for opacity, regressivity, and inequity. They are opaque because they are hidden from the consumers who bear their costs — one reason PPI and other polling tend to find tariffs a low-priority issue (pro or con) among working-class families. They are regressive because, in their role as a form of sales tax, they tax only goods, and less affluent families spend twice as much of their income on goods — clothes, shoes, cars, toothbrushes, Band-Aids, food, rugs, TVs, chairs — as rich families. Even today, tariffs account for a quarter of the cost of cheap shoes, and add 10% to the price of mass-market stainless steel forks and spoons. Adding another 10% or 20% tariff, or whatever the actual Trump administration policy turns out to be, to this adds immediately to their cash-register prices. A tariff increase, therefore, presages not only higher prices in the abstract — but higher prices mostly on things important to hourly-wage families. (And remember the Trump platform’s top single promise last year: “restore price stability, and quickly bring down prices”). And they are inequitable for businesses as well as families, since they tax goods-using industries — manufacturers, farmers, building contractors, retail outlets, restaurants — but not services- and investment-intensive sectors like financial services or real estate.

In trade policy, tariffs do have legitimate policy roles — for example, as part of a program to isolate aggressor governments (as with the removal of Russia’s MFN status in 2022), or giving temporary support to industries facing import surges or competitive troubles, and needing some space to upgrade. But policymakers should reserve tariffs for these kinds of unusual circumstances. The better trade policy approach is to build the export sector — a $3 trillion part of the U.S. economy, leading the world in farming, energy, and services exports, and second in the world for manufacturing — and find ways to promote it. Exporters pay high wages and earn a fifth of all U.S. farm income; they are disproportionately successful manufacturers, lead the world in cutting-edge innovation from digital technology to biotech, and range from world-famous medicine and aerospace firms to small chocolatiers and specialized musical-instrument makers. All are easy targets for the foreign governments who will retaliate against U.S. tariff hikes and breach of agreements. These are national assets, and policy should encourage their success, rather than turning them into trade war cannon fodder.

3. Stand by America’s allies and neighbors: Third, protect and build, rather than disrupt and erode, America’s strategic relationships with allies and neighbors. The U.S. is rare among historic world powers to have both long-term alliances with most of the world’s advanced economies, and deep and friendly ties with its immediate neighbors. These are strategic assets built over decades and core elements of any serious economic or national security strategy for the next decades.

So it is especially disturbing to see Mr. Trump use his free time in these transition months to pick fights, including through tariff threats, with neighbors and allies from Canada and Denmark to Mexico and Panama. Economics apart, these countries have often stood with the U.S. when it counted a lot. Remember, for example, that Denmark, with its 6 million people and 21,000 military personnel, lost 43 soldiers not so long ago in Iraq and Afghanistan. Canada lost 158. Neither deserves repayment with bullying and economic threats. Certainly, difficult policy issues and disputes turn up at times in alliance and big-neighbor relationships — military spending, export controls, border issues, narcotics control — are all important topics on which the U.S. has legitimate interests, and sometimes disagreements. But to think you can solve any of them more easily by alienating the relevant governments and publics is arrogant. And to forget the very large value we draw from mutually beneficial trade, technological partnerships, and cross-border investment with allies and neighbors is self-destructive folly. Democrats should stand by our alliances and good-neighbor relationships as major national strengths, even if the incoming administration hasn’t yet learned their value.

4. Provide a positive, reformist, alternative: Fourth, define the outlines of a better trade approach. Though a very detailed program is premature, three lines of policy can form a basic vision that offers both household and national benefit:

* International engagement: Pool strengths and deepen ties with neighbors and allies through updated, reciprocal trade agreements. Trade negotiations and agreements can help both find non-inflationary sources of growth by expanding markets for America’s exporting factories, farmers, energy, and services industries, and diversity and secure supply chains by deepening relationships with neighbors and allies. This can include U.S.-Europe agreements with the United Kingdom as an immediate choice, a return to the 15-country Trans-Pacific Partnership — now functioning very well as the “CPTPP” for Japan, Australia, and other allies, including the U.K. — and using the 2026 “review” of the “USMCA” to broaden it to Caribbean, Central, and South American countries. The content of such agreements would change in some ways from the FTAs negotiated in the 2000s — probably, for example, through coordination of export control policies vis-à-vis authoritarian countries, joint approaches to Chinese over-capacity, and subsidies in some industries, energy and LNG supply to Europe and Asia, secure access to and joint development of critical minerals and other essential industrial inputs, and other matters — but would remain in the internationalist strategic tradition.

* Domestic reform: Lower costs for families and industry. Balancing this outward-looking, optimistic approach to negotiations, move on from defending Constitutional government to restoring it, and from opposing regressive tariff hikes to developing a new approach that makes trade policy fairer and cuts costs for families. At a more personal level, Congress can ease the cost of living by reforming the permanent tariff system, stripping regressivity and sexism out of the clothing, silverware, shoe, and other consumer goods schedules — where hundreds of lines simply raise the prices of cheap mass-market goods not made in the U.S. for decades, and the higher rates imposed on women’s clothes as opposed to men’s extracts $2.5 billion from women each year — and making the functioning of this system transparent. Here the starting point is the Pink Tariffs Study Act introduced last spring by Representatives Lizzie Fletcher and Brittany Pettersen.

* Protect the Constitution: Finally, ensure Constitutionally appropriate policymaking by safeguarding Congress’ control over tariff rates. Here, the starting point is the Prevent Tariff Abuse bill introduced by Representatives Suzanne DelBene and Don Beyer, which bars the use of tariffs through the International Emergency Economic Powers Act.

CONCLUSION

These are of course starting points and principles meant as guidelines for a period of uncertainty and flux. They identify areas in which policymaking needs to be strengthened and guarded against abuse, new threats and destructive ideas to oppose, and lines of policy that can help families stretch their budgets, strengthen U.S. industries, and safeguard America’s place in the world.

In trade as in some other matters, the Trump administration is taking office next week with a variety of incompatible promises, threats, Hooverist rhetoric, and eccentric references to the late President William McKinley. This means the next years may create new challenges that analysts can intelligently guess at but can’t predict with real precision, and a detailed response will have to. But though even a week before the inauguration, its program ain’t exactly clear, two things do seem certain:

One, Mr. Trump’s tariff threats — whichever among them proves to be the “real” policy — are bad ideas. All of them, though in different ways, would leave Americans with lower living standards, higher-cost and less competitive businesses, and eroded national security.

Two, critics of these threats should not repeat the Biden administration’s attempts to blur differences with Trumpism and propose softer versions of it. Instead, they need a forthright critique and an alternative that can deliver the opposite of Trumpism: a lower cost of living, more competitive agriculture and industries, and a stronger position in a more dangerous world.

India has 84 of the world’s 100 most air-polluted cities.

FACT: India has 84 of the world’s 100 most air-polluted cities.

THE NUMBERS: Share of annual deaths attributable to air pollution* –

Rest of world: ~8%* World Bank for India, calculations based on national data for Pakistan and Bangladesh.WHAT THEY MEAN:

The annual urban air quality survey by IQ Air (a Swiss air purification company) reports “PM 2.5” concentration per cubic meter of air in 7,812 cities in 134 countries and territories. (Punta Arenas to Nome; Dublin to Vladivostok; Cape Town to Oslo; Cairo, Dushanbe, Suva, Colombo, Chiang Rai, Sydney, etc.) PM 2.5 is “particulate matter” measuring 2.5 microns or less in diameter. Typically it’s smoke, soot, effluent, car exhaust, small acid drops produced by atmospheric chemical reactions, and the like. The survey’s 2024 edition, with figures for 2023, finds the world’s healthiest air in Kuusamo, a Finnish town of 15,000 about 500 miles due north of Helsinki. They breathe in just 0.3 micrograms of particulate matter per cubic meter of air. At the smoggy top, meanwhile, comes Begusarai, a Bihar industrial center with 3 million residents, at 118.9 micrograms per cubic meter.

Begusarai’s case is extreme but also representative: 84 Indian cities and towns show up in the survey’s 100 most air-polluted cities. National capital New Delhi comes in at 92.7 micrograms, Patna 88.2, Gwalior 68.9, and Meerut 78.9. Another six of the top ten are Bangladeshi and Pakistani towns — Lahore ranks fifth, just above New Delhi, and Dhaka is 24th — each with over 50 micrograms of dirt per cubic meter of air. In sum, the belt of fertile green land below the Himalaya and north of the Deccan Plateau, home to over a billion people, has the worst air in the world. This, in part, comes from geography (the Himalaya range is the world’s largest winter air-flow trapper) but also from poor policing of brick kilns, rubbish-burning, crop residue burnoff, vehicle emissions, and other sources policy can, in principle, address.

Three ways to put these numbers in context:

Compared to other big emerging-economy cities: City air is usually smokier in emerging economies than in top-end wealthy countries, but the Pakistan-northern India-Bangladesh belt is unique. For example, IQ Air puts Lagos’ PM 2.5 count at 21.8 micrograms per cubic meter of air, a fifth of the Delhi level. Mexico City’s is 22.3 micrograms, and Istanbul’s at 18.7. Others include Bangkok at 21.7, Cairo a dense 42.7, Shanghai 28.7, and Sao Paulo 14.3.

Compared to the U.S.: American cities and towns nationally averaged 9.1 micrograms, just between Germany’s 9.0 micrograms and Argentina’s 9.2, and in the mid-range of wealthy countries. (See below for a representative list.) Big American cities range from Chicago’s relatively smoky 13.0 micrograms to Tucson’s desert-fresh 3.8; San Juan in Puerto Rico, with a sparkling 2.7 microgram reading, gets IQ Air’s title as the world’s cleanest-air capital. Coraopolis in Pennsylvania fared worst at 19.3 micrograms, but mainly by bad luck — Coraopolis was directly in the path of that June’s Canadian wildfire smoke river, and its 2022 rating was a better 7.2 micrograms.

Compared to other regions: In Europe, the highest continental air pollution rating goes to Plevlja in Montenegro at 40.7 micrograms per cubic meter. (It’s near a coal mine and a Yugoslav-era power plant.) The western hemisphere’s top reading is in Chilean mountain town Coyhaique at 33.2 micrograms. though both are smoky by American and “developed-world-city” standards, neither would make a list of South Asia’s 150 most-polluted cities.

What does this mean? High particulate matter counts aren’t merely unpleasant. The World Bank says they engender or inflame enough illnesses each year – heart diseases, strokes, lung cancer, a smaller number of lung infections — to cause 1.67 million Indian premature deaths to air pollution. That’s nearly a fifth of India’s 9.5 million total annual deaths; the comparable estimate for Bangladesh is about 160,000 of 859,000 deaths, and for Pakistan 128,000 of 1.6 million deaths. Overall, the World Health Organization attributes 6.7 million premature deaths to air pollution worldwide, or one in nine of the world’s annual 61.7 million deaths.

Two concluding thoughts: First, it’s rare to solve a problem before you recognize it, and the survey’s very broad coverage shows rapidly growing worldwide interest in understanding air quality levels. So the high-P.M. 2.5 countries participating in the survey deserve credit for transparency. (The regions least covered are the Middle East and sub-Saharan Africa.) Second, air pollution is not immune to policy. The U.S.’ national PM 2.5 average, for example, was 13.5 micrograms per cubic meter in 2000, so the 9.1 micrograms of 2023 represents a 30% cleanup so far this century. Likewise, Beijing’s 34.1 microgram count, though nothing to brag about, is vastly better than the New Delhi-like 101.6 micrograms in 2013. So policy can help. The cities and national governments at the top end of the list have the information they need to do better, and ought to use it. In this case, the “people are dying” cliché seems perfectly true, lots of them.

Further Reading

IQ Air’s World Air Quality 2024 report.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency explains “PM 2.5” and U.S. clean air laws.

And the World Health Organization on air pollution as a cause of death.

Top and bottom:

Kuusamo, just south of the 66th parallel — for American readers, about 80 miles north of Nome and Fairbanks –advertises excellent skiing seven months a year, as well as the world’s freshest air. If you’re planning a vacation, though, note that in this winter season, Kuusamo gets less than four hours of sunlight. Tomorrow’s dawn is 10:14 a.m., and darkness returns by lunchtime at 2:06 p.m.

Begusarai residents, meanwhile, can check in with Bihar’s air quality monitoring service to see whether it’s safe to go outside.

South Asia:

al-Jazeera asks why South Asia’s air is so bad.

The World Bank looks at ideas and air quality policy in India.

… and finds overuse of brick kilns and home ovens burning wood and other biomass as core causes of Bangladesh’s highest-in-the-world national PM 2.5 rating.

Pakistan’s College of Physicians and Surgeons looks at health and air quality challenges.

Rankings (cities):

Here’s a selection of 60 of the report’s 7,812 cities, illustrating (a) the worldwide range from Kuusumo’s 7,812th-place 0.3 micrograms per cubic meter of air to Begusarai’s top-ranked 118.9, and (b) the U.S. range (American cities in italics) from the low of 1.9 micrograms in Wilson, N.C., to Coraopoli

| Rank | City | PM 2.5 micrograms per cubic meter |

| 1 | Begusarai, India | 118.9 |

| 2 | Gauwahati, India | 105.4 |

| 5 | Lahore, Pakistan | 99.7 |

| 6 | New Delhi, India | 92.7 |

| 24 | Dhaka, Bangladesh | 65.8 |

| 231 | Jakarta, Indonesia | 43.8 |

| 233 | Hanoi, Vietnam | 43.7 |

| 258 | Cairo, Egypt | 42.4 |

| 284 | Kathmandu, Nepal | 42.0 |

| 321 | Chengdu, China | 39.0 |

| 454 | Beijing, China | 34.1 |

| 488 | Accra, Ghana | 33.2 |

| 667 | Shanghai, China | 28.7 |

| 958 | Phnom Penh, Cambodia | 22.8 |

| 999 | Mexico City, Mexico | 22.3 |

| 1048 | Lagos, Nigeria | 21.8 |

| 1052 | Bangkok, Thailand | 21.7 |

| 1206 | Seoul, Korea | 19.7 |

| 1246 | Coraopolis, PA | 19.3 |

| 1301 | Istanbul, Turkey | 18.7 |

| 1315 | Thessaloniki, Greece | 18.5 |

| 1633 | Jerusalem, Israel | 15.7 |

| 1659 | Hong Kong, China | 15.5 |

| 1711 | Tegucigalpa, Honduras | 15.1 |

| 1771 | Makati, Philippines | 14.8 |

| 1840 | Sao Paulo, Brazil | 14.3 |

| 2026 | Singapore, Singapore | 13.4 |

| 2071 | Warsaw, Poland | 13.2 |

| 2086 | Florence, Italy | 13.1 |

| 2120 | Chicago, IL | 13.0 |

| 2210 | La Paz, Bolivia | 12.6 |

| 2357 | St. Louis, MO | 12.2 |

| 2563 | Washington, D.C. | 11.7 |

| 2627 | New York, NY | 11.6 |

| 2906 | Atlanta, GA | 11.0 |

| 2990 | Toronto, Canada | 10.8 |

| 3158 | Houston, TX | 10.6 |

| 3179 | Berlin, Germany | 10.5 |

| 3196 | Nairobi, Kenya | 10.5 |

| 3422 | Marseilles, France | 10.1 |

| 3702 | Tokyo, Japan | 9.7 |

| 3754 | Buenos Aires, Argentina | 9.6 |

| 3890 | Los Angeles, CA | 9.5 |

| 4053 | Lviv, Ukraine | 9.3 |

| 4279 | Madrid, Spain | 9.0 |

| 4672 | New Orleans, LA | 8.6 |

| 4830 | London, United Kingdom | 8.4 |

| 5215 | Copenhagen, Denmark | 7.9 |

| 5281 | Boston, MA | 7.9 |

| 5470 | Lisbon, Portugal | 7.0 |

| 5828 | York, United Kingdom | 7.1 |

| 5853 | Missoula, MT | 7.1 |

| 5888 | Sapporo, Japan | 7.0 |

| 6305 | Denver, CO | 6.4 |

| 6575 | Cape Town, South Africa | 5.9 |

| 6872 | Stockholm, Sweden | 5.4 |

| 7087 | Sydney, Australia | 5.0 |

| 7100 | Tallin, Estonia | 4.6 |

| 7635 | Tucson, AZ | 3.5 |

| 7692 | Wellington, New Zealand | 3.1 |

| 7753 | San Juan, PR | 2.7 |

| 7806 | Wilson, NC | 1.9 |

| 7812 | Kuusamo, Finland | 0.3 |

Rankings (countries):

Shifting from cities to countries, only ten countries meet WHO’s “healthy air” standard of 5.0 micrograms of particulate matter per cubic meter of air. Most are small islands such as Tahiti, Mauritius, Bermuda, and Iceland. The best big-country records are Australia’s and New Zealand’s, with Baltic Sea countries Estonia, Finland, and Sweden also very good. On any given afternoon, Bangladesh’s 79.9 micrograms of particulate matter per cubic meter means Bangladeshis are breathing 20 times as much dirt as New Zealanders, with their best-in-class 4.3 micrograms. A sample:

| Rank | Country | PM 2.5 micrograms per cubic meter |

| 1. | Bangladesh | 79.9 |

| 2. | Pakistan | 73.7 |

| 3. | India | 54.4 |

| 7. | United Arab Emirates | 43.0 |

| 14. | Indonesia | 37.1 |

| 19. | China | 32.5 |

| 29. | Ethiopia | 29.0 |

| 35. | Nigeria | 23.9 |

| 46. | Mexico | 20.1 |

| 50. | Korea | 19.2 |

| 74. | Poland | 14.3 |

| 83. | Brazil | 12.6 |

| 96. | Japan | 9.6 |

| 102. | United States | 9.1 |

| 103. | Germany | 9.0 |

| 112. | United Kingdom | 7.7 |

| 117. | Jamaica | 7.1 |

| 124. | Sweden | 5.1 |

| 128. | Australia | 4.5 |

| 129. | New Zealand | 4.3 |

| 134. | French Polynesia | 3.2 |

America’s worst air day:

The 2023 Canadian wildfire smoke event peaked on June 8. That day’s PM 2.5 readings, the 21st century’s worst for the United States, reached 196 micrograms per cubic meter in New York and 141 micrograms in Washington, D.C. — that is, levels typical of a bad but not unusual week in northern Indian cities. The day’s national average was 27.5 micrograms. The Guardian looks back.

… and the Washington Post lets you look up that day’s PM 2.5 ratings by city:

And last:

A morbid chart from Our World in Data counts total annual world deaths. Note the sharp spike in 2020 during the COVID pandemic, from 58.4 million deaths in 2019 to 69.7 million in 2020, followed by a drop back to last year’s 61.7 million.

ABOUT ED

Ed Gresser is Vice President and Director for Trade and Global Markets at PPI.

Ed returns to PPI after working for the think tank from 2001-2011. He most recently served as the Assistant U.S. Trade Representative for Trade Policy and Economics at the Office of the United States Trade Representative (USTR). In this position, he led USTR’s economic research unit from 2015-2021, and chaired the 21-agency Trade Policy Staff Committee.

Ed began his career on Capitol Hill before serving USTR as Policy Advisor to USTR Charlene Barshefsky from 1998 to 2001. He then led PPI’s Trade and Global Markets Project from 2001 to 2011. After PPI, he co-founded and directed the independent think tank ProgressiveEconomy until rejoining USTR in 2015. In 2013, the Washington International Trade Association presented him with its Lighthouse Award, awarded annually to an individual or group for significant contributions to trade policy.

Ed is the author of Freedom from Want: American Liberalism and the Global Economy (2007). He has published in a variety of journals and newspapers, and his research has been cited by leading academics and international organizations including the WTO, World Bank, and International Monetary Fund. He is a graduate of Stanford University and holds a Master’s Degree in International Affairs from Columbia Universities and a certificate from the Averell Harriman Institute for Advanced Study of the Soviet Union.

Read the full email and sign up for the Trade Fact of the Week.

PPI Statement on Biden’s Decision to Block Nippon Steel Purchase of U.S. Steel

Today, PPI issued the following statement in response to President Biden’s decision on Nippon Steel’s purchase of U.S. Steel:

“President Biden’s decision this morning to block Nippon Steel’s purchase of U.S. Steel is a bad mistake on the merits, and the White House’s explanation of the reasons is so opaque and so lacking in substance as to suggest that it knows this. Here is the core of the release (with ellipses stripping out some legal language):

‘(a) There is credible evidence that leads me to believe that … Nippon Steel Corporation … through the proposed acquisition of United States Steel Corporation … might take action that threatens to impair the national security of the United States; and

‘(b) Provisions of law, other than section 721 and the International Emergency Economic Powers Act … do not, in my judgment, provide adequate and appropriate authority for me to protect the national security in this matter.’

“Nothing in the release hints in any way as to what ‘action’ Nippon Steel might take and how it might differ from the actions of the company’s steelmaking facilities in Alabama for over a decade. Neither does it suggest what the ‘credible evidence’ the statement mentions might involve. Still, less does the release offer any way to resolve the questions raised if this mutually agreed-upon transaction doesn’t go ahead:

- Will U.S. Steel now follow through on its statement earlier this year that blocking the transaction would lead to the closure of western Pennsylvania steel mills? If so, how would the administration explain its decision to the affected communities and workers?

- How does the administration view the possibility of a blast-furnace steel monopoly emerging as a result of an alternative purchase, and its impact on downstream industries such as auto production?

- Does the administration, in general, feel that foreign investors from allied countries such as Japan, Korea, the European Union, Canada, and the U.K., who employ a quarter of all U.S. manufacturing workers, are unreliable?

“Looking forward, it is very likely to have set a bad precedent for future CFIUS (Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States) decisions on sensitive transactions, which up to now have been civil-service driven and based on objective criteria. As such, it does a disservice to U.S. businesses, to foreign firms interested in manufacturing and employing skilled workers in the United States, and to consumers and unions sharing an interest in transparent decision-making with a clear statutory basis. It also creates deep uncertainty about the future of U.S. Steel, and in particular, its Pennsylvania operations.

“Little about the rationale for this very controversial decision, with its attendant damage to an important alliance and its potential harm to American heavy industry, is clear. The Biden administration owes the country a better explanation, and we hope it will provide one in its remaining days.”

The Progressive Policy Institute (PPI) is a catalyst for policy innovation and political reform based in Washington, D.C. Its mission is to create radically pragmatic ideas for moving America beyond ideological and partisan deadlock. Learn more about PPI by visiting progressivepolicy.org. Find an expert at PPI and follow us on Twitter.

Follow the Progressive Policy Institute.

###

Media Contact: Ian O’Keefe, iokeefe@ppionline.org

Tariffs and their Failings: A Higher U.S. Tariff Would Would Raise Prices, Erode U.S. Competitiveness, and Endanger Exporters

Testimony from Edward Gresser

Joint Economic Committee

December 18, 2024

Mr. Chairman and Members of the Committee: