As the Progressive Policy Institute’s Center for Funding America’s Future wraps up its first year, we want to thank everyone who followed and supported our work. Below you’ll find a compilation of our contributions to the public discourse in 2018.

Through op-eds, blog posts, media interviews, research reports, engagement with elected officials, and public forums organized in key battleground states, the Center drew much-needed attention to America’s interconnected problems of deteriorating public investment and soaring federal budget deficits. We fought back against Republican efforts to make these problems worse and challenged Democrats to counter them by offering a new progressivism that invests in our country without leaving the bill for future generations.

We concluded the year with a public forum in Iowa to kick off the 2020 presidential debate over fiscal issues in the nation’s first caucus state – and this is only the beginning. Now that we’ve made the case for a fiscally responsible public investment agenda that fosters robust and inclusive economic growth, we’re ready to offer concrete proposals for making it a reality.

In 2019, PPI will publish a series of specific policy recommendations to renew public investments in the foundation of our economy, modernize federal health and retirement programs to reflect an aging society, and enact pro-growth tax reform that raises the revenue necessary to support both of these critical government functions. We’re excited for the year ahead and hope you’ll continue to follow our work in 2019 and beyond.

Read Our Major Reports

Ending America’s Public Investment Drought

Ben Ritz and Brendan McDermott (12/19)

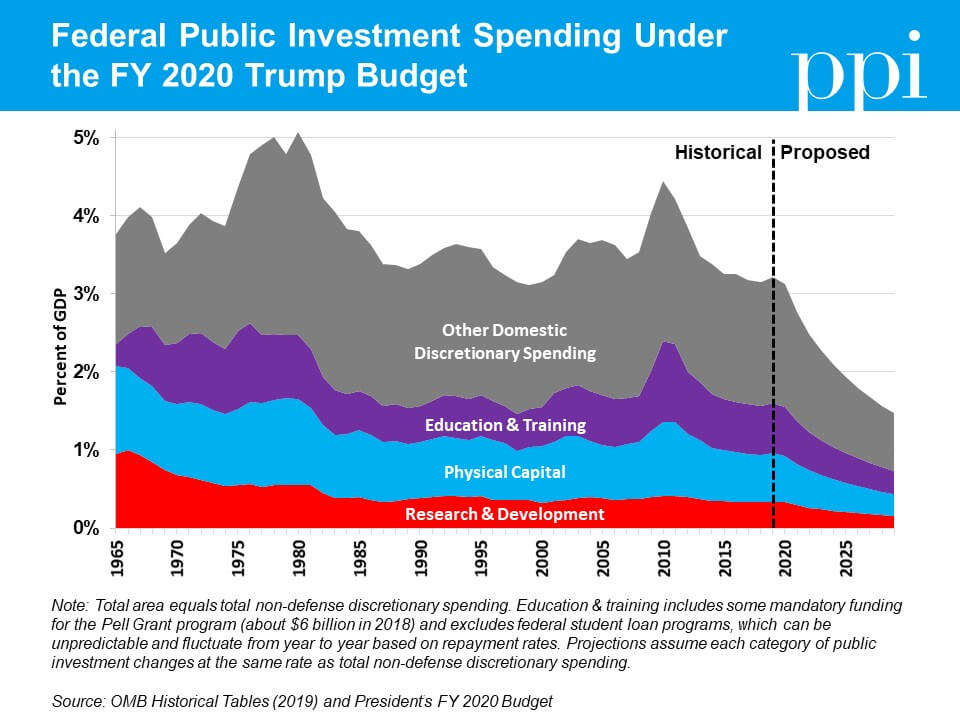

Defunding America’s Future: The Squeeze on Public Investment in the United States

Ben Ritz (10/15)

Watch Our Public Forums

Ending America’s Public Investment Drought – Des Moines, IA (12/19)

Former U.S. Secretary of Agriculture and Iowa Governor Tom Vilsack

Former Iowa Lieutenant Governor Patty Judge

Iowa Rep. Chris Hall, Ranking Member on the House Appropriations Committee

Ben Ritz, Director of PPI’s Center for Funding America’s Future

Moderated by PPI President Will Marshall

Defunding America’s Future – Philadelphia, PA (11/19)

U.S. Rep. Madeline Dean (D-PA)

Dr. Robert Inman, Professor of Finance at the Wharton School

Ben Ritz, Director of PPI’s Center for Funding America’s Future

Moderated by David Thornburgh, CEO of Committee of Seventy

Check Out Our Op-Eds and Media Coverage

DC Think Tank Urging Iowans to Ask Presidential Candidates About Infrastructure

O. Kay Henderson, Radio Iowa (12/22)

A Fitting End for Disgraceful House Republicans

Ben Ritz, Forbes (12/22)

Social Security, Public Projects and Rural America with Tom Vilsack (Radio)

Michael Libbie, Insight on the Business Hour on News/Talk 1540 KXEL (12/20)

American Children are Getting a Raw Deal Under GOP Leadership

Brodi Fontenot, The Hill (12/20)

Top Democrats Host Policy Roundtable (TV)

ABC 5, Des Moines (12/19)

Trump Once Again Shows Contempt for Young Americans

Ben Ritz, Forbes (12/6)

Welcome to Post-Thrift America

Andrew Yarrow, RealClearPolicy (12/04)

Victorious Democrats Should Thank Young Voters by Funding America’s Future

Ben Ritz, Forbes (11/8)

Reality Check 10.17.18 (Radio)

Charles Ellison, WURD Radio Philadelphia (10/17)

Defend or Defund Our Future? (Radio)

Chase Hagaman, Facing the Future on NH News Radio WKXL (10/16)

Time to Get DC’s Finances Under Control

Paul Weinstein, RealClearPolicy (10/17)

The Deficit Is Heading to $1 Trillion. How Worried Should We Be?

Michael Rainey, The Fiscal Times (9/24)

Democrats Must Bridge the Generational Divide to Prevent Climate and Budget Crises

Paul Bledsoe and Ben Ritz, The Hill (7/18)

How Trump and Republicans are Damning Social Security and Medicare

Ben Ritz, NY Daily News (6/14)

Making Social Security’s Retirement Age Work for Workers

Andy Rotherham, The Hill (6/8)

Medicare is Running Out of Money. Democrats Want to Expand It

W. James Antle III, Washington Examiner (6/7)

The Deficit Debate

David Leonhardt, The New York Times (4/20)

The Parallel Universe of Trump’s Budget, Explained

Sam Petulla and Gregory Krieg, CNN (2/13)

Welcome to a New Era of Federal Spending

Sam Petulla, CNN (2/10)

12 of the Most Important Things in Congress’s Massive Spending Deal

Heather Long and Jeff Stein, The Washington Post (2/8)

Find More Analysis on the PPI Blog

Republicans Double Down on Deepening Deficits (9/13)

CBO Report Shows That We Really Can’t Afford All These Tax Cuts (8/9)

New Projections Make Clear We Can’t Afford the Trump Agenda (6/27)

Before Expanding Medicare, We Have to Pay for Current Beneficiaries (6/7)

Trustees Reports Highlight Challenges Facing Medicare and Social Security (6/6)

CBO Analysis Exposes Trump’s Faulty Fiscal Policy (5/30)

Are Democrats Really the Party of Fiscal Responsibility? Part 2 (4/19)

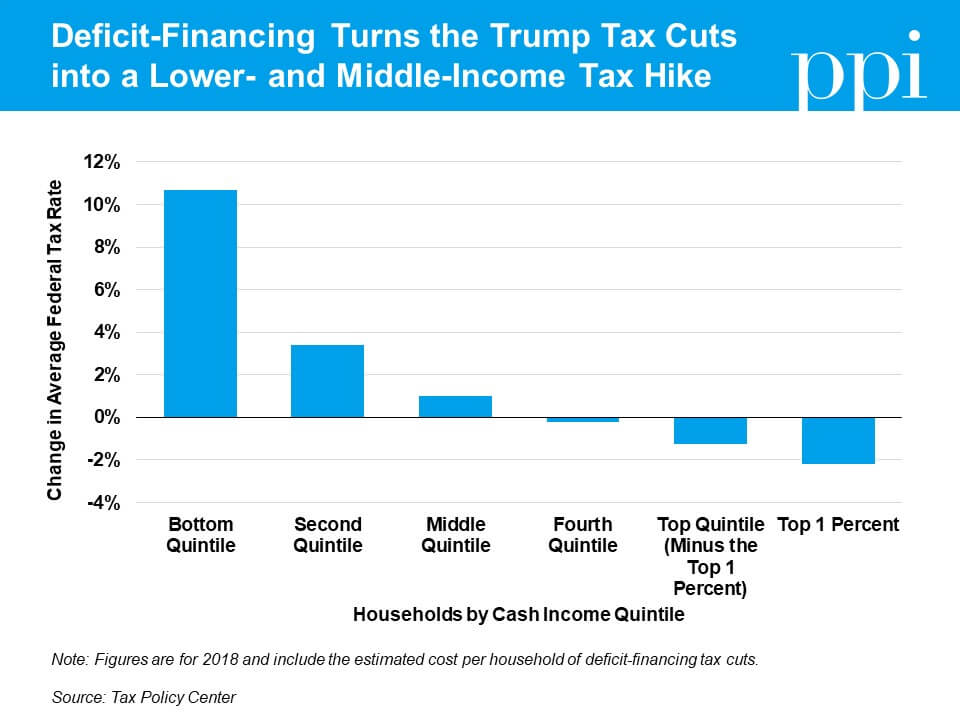

A Tax Day Review of Trump’s “Tax Cuts” (4/17)

Are Democrats Really the Party of Fiscal Responsibility? Yes, But… (4/16)

PPI Analysis of CBO’s 2018 Budget and Economic Outlook (4/10)

House GOP’s Balanced Budget Amendment is a Sham (4/10)

Even After Budget Deal, Discretionary Spending Remains Low (3/14)

New Analysis Highlights Dire Fiscal Situation (3/5)

Six Charts That Reveal the Absurdity of the Trump Budget (2/14)

See Our Press Releases

PPI Kicks Off 2020 Economic Debate with Iowa Fiscal Forum (12/19)

New Report: Washington is Crippling America’s Economic Future (10/15)

Social Security & Medicare Trustees Reports: A Reality Check for Expansion Advocates & Tax Cutters Alike (6/5)

New CBO Report Highlights the Cost of Trump’s First Year (4/9)

Statement on the Passing of Peter G. Peterson (3/20)

PPI Launches Center for Funding America’s Future (2/12)

Don’t Help GOP Budget Busters (2/8)